Hyper-threading (officially called Hyper-Threading Technology or HT Technology and abbreviated as HTT or HT) is Intel's proprietary simultaneous multithreading (SMT) implementation used to improve parallelization of computations (doing multiple tasks at once) performed on x86 microprocessors. It was introduced on Xeon server processors in February 2002 and on Pentium 4 desktop processors in November 2002.[4] Since then, Intel has included this technology in Itanium, Atom, and Core 'i' Series CPUs, among others.[5]

For each processor core that is physically present, the operating system addresses two virtual (logical) cores and shares the workload between them when possible. The main function of hyper-threading is to increase the number of independent instructions in the pipeline; it takes advantage of superscalar architecture, in which multiple instructions operate on separate data in parallel. With HTT, one physical core appears as two processors to the operating system, allowing concurrent scheduling of two processes per core. In addition, two or more processes can use the same resources: If resources for one process are not available, then another process can continue if its resources are available.

In addition to requiring simultaneous multithreading support in the operating system, hyper-threading can be properly utilized only with an operating system specifically optimized for it.[6]

Overview

Hyper-Threading Technology is a form of simultaneous multithreading technology introduced by Intel, while the concept behind the technology has been patented by Sun Microsystems. Architecturally, a processor with Hyper-Threading Technology consists of two logical processors per core, each of which has its own processor architectural state. Each logical processor can be individually halted, interrupted or directed to execute a specified thread, independently from the other logical processor sharing the same physical core.[8]

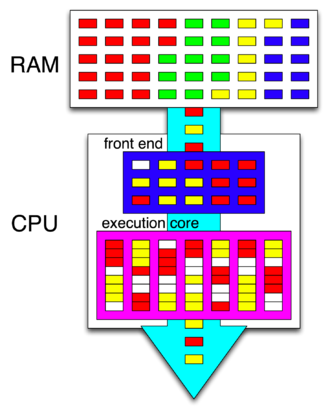

Unlike a traditional dual-processor configuration that uses two separate physical processors, the logical processors in a hyper-threaded core share the execution resources. These resources include the execution engine, caches, and system bus interface; the sharing of resources allows two logical processors to work with each other more efficiently, and allows a logical processor to borrow resources from a stalled logical core (assuming both logical cores are associated with the same physical core). A processor stalls when it must wait for data it has requested, in order to finish processing the present thread. The degree of benefit seen when using a hyper-threaded, or multi-core, processor depends on the needs of the software, and how well it and the operating system are written to manage the processor efficiently.[8]

Hyper-threading works by duplicating certain sections of the processor—those that store the architectural state—but not duplicating the main execution resources. This allows a hyper-threading processor to appear as the usual "physical" processor plus an extra "logical" processor to the host operating system (HTT-unaware operating systems see two "physical" processors), allowing the operating system to schedule two threads or processes simultaneously and appropriately. When execution resources in a hyper-threaded processor are not in use by the current task, and especially when the processor is stalled, those execution resources can be used to execute another scheduled task. (The processor may stall due to a cache miss, branch misprediction, or data dependency.)[9]

This technology is transparent to operating systems and programs. The minimum that is required to take advantage of hyper-threading is symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) support in the operating system, since the logical processors appear no different to the operating system than physical processors.

It is possible to optimize operating system behavior on multi-processor, hyper-threading capable systems. For example, consider an SMP system with two physical processors that are both hyper-threaded (for a total of four logical processors). If the operating system's thread scheduler is unaware of hyper-threading, it will treat all four logical processors the same. If only two threads are eligible to run, it might choose to schedule those threads on the two logical processors that happen to belong to the same physical processor. That processor would be extremely busy, and would share execution resources, while the other processor would remain idle, leading to poorer performance than if the threads were scheduled on different physical processors. This problem can be avoided by improving the scheduler to treat logical processors differently from physical processors, which is, in a sense, a limited form of the scheduler changes required for NUMA systems.

History

The first published paper describing what is now known as hyper-threading in a general purpose computer was written by Edward S. Davidson and Leonard. E. Shar in 1973.[10]

Denelcor, Inc. introduced multi-threading with the Heterogeneous Element Processor (HEP) in 1982. The HEP pipeline could not hold multiple instructions from the same process. Only one instruction from a given process was allowed to be present in the pipeline at any point in time. Should an instruction from a given process block the pipe, instructions from other processes would continue after the pipeline drained.

US patent for the technology behind hyper-threading was granted to Kenneth Okin at Sun Microsystems in November 1994. At that time, CMOS process technology was not advanced enough to allow for a cost-effective implementation.[11]

Intel implemented hyper-threading on an x86 architecture processor in 2002 with the Foster MP-based Xeon. It was also included on the 3.06 GHz Northwood-based Pentium 4 in the same year, and then remained as a feature in every Pentium 4 HT, Pentium 4 Extreme Edition and Pentium Extreme Edition processor since. The Intel Core & Core 2 processor lines (2006) that succeeded the Pentium 4 model line didn't utilize hyper-threading. The processors based on the Core microarchitecture did not have hyper-threading because the Core microarchitecture was a descendant of the older P6 microarchitecture. The P6 microarchitecture was used in earlier iterations of Pentium processors, namely, the Pentium Pro, Pentium II and Pentium III (plus their Celeron & Xeon derivatives at the time). Windows 2000 SP3 and Windows XP SP1 have added support for hyper-threading.

Intel released the Nehalem microarchitecture (Core i7) in November 2008, in which hyper-threading made a return. The first generation Nehalem processors contained four physical cores and effectively scaled to eight threads. Since then, both two- and six-core models have been released, scaling four and twelve threads respectively.[12] Earlier Intel Atom cores were in-order processors, sometimes with hyper-threading ability, for low power mobile PCs and low-price desktop PCs.[13] The Itanium 9300 launched with eight threads per processor (two threads per core) through enhanced hyper-threading technology. The next model, the Itanium 9500 (Poulson), features a 12-wide issue architecture, with eight CPU cores with support for eight more virtual cores via hyper-threading.[14] The Intel Xeon 5500 server chips also utilize two-way hyper-threading.[15][16]

Performance claims

According to Intel, the first hyper-threading implementation used only 5% more die area than the comparable non-hyperthreaded processor, but the performance was 15–30% better.[17][18] Intel claims up to a 30% performance improvement compared with an otherwise identical, non-simultaneous multithreading Pentium 4. Tom's Hardware states: "In some cases a P4 running at 3.0 GHz with HT on can even beat a P4 running at 3.6 GHz with HT turned off."[19] Intel also claims significant performance improvements with a hyper-threading-enabled Pentium 4 processor in some artificial-intelligence algorithms.

Overall the performance history of hyper-threading was a mixed one in the beginning. As one commentary on high-performance computing from November 2002 notes:[20]

Hyper-Threading can improve the performance of some MPI applications, but not all. Depending on the cluster configuration and, most importantly, the nature of the application running on the cluster, performance gains can vary or even be negative. The next step is to use performance tools to understand what areas contribute to performance gains and what areas contribute to performance degradation.

As a result, performance improvements are very application-dependent;[21] however, when running two programs that require full attention of the processor, it can actually seem like one or both of the programs slows down slightly when Hyper-Threading Technology is turned on.[22] This is due to the replay system of the Pentium 4 tying up valuable execution resources, equalizing the processor resources between the two programs, which adds a varying amount of execution time. The Pentium 4 "Prescott" and the Xeon "Nocona" processors received a replay queue that reduces execution time needed for the replay system and completely overcomes the performance penalty.[23]

According to a November 2009 analysis by Intel, performance impacts of hyper-threading result in increased overall latency in case the execution of threads does not result in significant overall throughput gains, which vary[21] by the application. In other words, overall processing latency is significantly increased due to hyper-threading, with the negative effects becoming smaller as there are more simultaneous threads that can effectively use the additional hardware resource utilization provided by hyper-threading.[24] A similar performance analysis is available for the effects of hyper-threading when used to handle tasks related to managing network traffic, such as for processing interrupt requests generated by network interface controllers (NICs).[25] Another paper claims no performance improvements when hyper-threading is used for interrupt handling.[26]

Drawbacks

When the first HT processors were released, many operating systems were not optimized for hyper-threading technology (e.g. Windows 2000 and Linux older than 2.4).[27]

In 2006, hyper-threading was criticised for energy inefficiency.[28] For example, ARM (a specialized, low-power, CPU design company), stated that simultaneous multithreading can use up to 46% more power than ordinary dual-core designs. Furthermore, they claimed that SMT increases cache thrashing by 42%, whereas dual core results in a 37% decrease.[29]

In 2010, ARM said it might include simultaneous multithreading in its future chips;[30] however, this was rejected in favor of their 2012 64-bit design.[31] ARM produced SMT cores in 2018.[32]

In 2013, Intel dropped SMT in favor of out-of-order execution for its Silvermont processor cores, as they found this gave better performance with better power efficiency than a lower number of cores with SMT.[33]

In 2017, it was revealed that Intel's Skylake and Kaby Lake processors had a bug in their implementation of hyper-threading that could cause data loss.[34] Microcode updates were later released to address the issue.[35]

In 2019, with Coffee Lake, Intel temporarily moved away from including hyper-threading in mainstream Core i7 desktop processors except for highest-end Core i9 parts or Pentium Gold CPUs.[36] It also began to recommend disabling hyper-threading, as new CPU vulnerability attacks were revealed which could be mitigated by disabling HT.[37]

Security

In May 2005, Colin Percival demonstrated that a malicious thread on a Pentium 4 can use a timing-based side-channel attack to monitor the memory access patterns of another thread with which it shares a cache, allowing the theft of cryptographic information. This is not actually a timing attack, as the malicious thread measures the time of only its own execution. Potential solutions to this include the processor changing its cache eviction strategy or the operating system preventing the simultaneous execution, on the same physical core, of threads with different privileges.[38] In 2018 the OpenBSD operating system has disabled hyper-threading "in order to avoid data potentially leaking from applications to other software" caused by the Foreshadow/L1TF vulnerabilities.[39][40] In 2019 a set of vulnerabilities led to security experts recommending the disabling of hyper-threading on all devices.[41]

See also

References

External links

- Intel Demonstrates Breakthrough Processor Design, a press release from August 2001

- Intel – high level overview of Hyper-threading

- Hyper-threading on MSDN Magazine

- introductory article from Ars Technica

- US Patent Number 4,847,755

- Merom, Conroe, Woodcrest lose HyperThreading

- ZDnet: Hyperthreading hurts server performance, say developers

- ARM is no fan of HyperThreading - Outlines problems of SMT solutions

- The Impact of Hyper-Threading on Processor Resource Utilization in Production Applications