Kongo or Kikongo is one of the Bantu languages spoken by the Kongo people living in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Republic of the Congo, Gabon, and Angola. It is a tonal language. The vast majority of present-day speakers live in Africa. There are roughly seven million native speakers of Kongo in the above-named countries. An estimated five million more speakers use it as a second language.[1]

| Kongo | |

|---|---|

| Kikongo | |

| Native to | DR Congo (Kongo Central), Angola, Republic of the Congo, Gabon |

| Ethnicity | Kongo |

Native speakers | (L1: 6.0 million cited 1982–2021)[1] L2: 5.0 million (2021)[1] |

| Latin, Mandombe | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | National language and unofficial language: |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | kg |

| ISO 639-2 | kon |

| ISO 639-3 | kon – inclusive codeIndividual codes: kng – Koongoldi – Ladi, Laadi, Lari or Laarikwy – San Salvador Kongo (South)yom – Yombe |

| Glottolog | yomb1244 Yombe |

H.14–16[2] | |

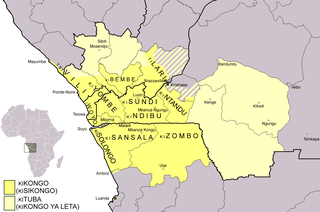

Map of the area where Kongo and Kituba are spoken, Kituba as a lingua franca. Kisikongo (also called Kisansala by some authors) is the Kikongo spoken in Mbanza Kongo. | |

| The Kongo language | |

|---|---|

| Person | muKongo, musi Kongo, muisi Kongo, mwisi Kongo, nKongo |

| People | baKongo, bisi Kongo, besi Kongo, esiKongo, aKongo |

| Language | kiKongo |

Historically, it was spoken by many of those Africans who for centuries were taken captive, transported across the Atlantic, and sold as slaves in the Americas. For this reason, creolized forms of the language are found in ritual speech of Afro-American religions, especially in Brazil, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Suriname. It is also one of the sources of the Gullah language, which formed in the Low Country and Sea Islands of the United States Southeast.[3] The Palenquero creole in Colombia is also related to Kong creole.

Geographic distribution

Kongo was the language of the Kingdom of Kongo prior to the creation of Angola by the Portuguese Crown in 1575. The Berlin Conference (1884-1885) among major European powers divided the rest of the kingdom into three territories. These are now parts of the DRC (Kongo Central and Bandundu), the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon.

Kikongo is the base for the Creole language Kituba, also called Kikongo de l'État and Kikongo ya Leta (French and Kituba, respectively, for "Kikongo of the state administration" or "Kikongo of the State").[4]

The constitution of the Republic of the Congo uses the name Kituba,[5] and Democratic Republic of the Congo uses the term Kikongo.[6] Kituba (i.e. Kikongo ya Leta) is used as the term in the DRC administration. This can be explained by the fact that Kikongo ya Leta is often mistakenly called Kikongo (i.e. KiNtandu, KiManianga, KiNdibu, etc.).[7][4][8]

Kikongo and Kituba are spoken in:

- South of Republic of the Congo :

- Kikongo (Yombe, Vili, Ladi, Sundi, etc.) and Kituba :

- Kouilou,

- Niari,

- Bouenza,

- Lékoumou,

- south of Brazzaville,

- Pointe-Noire,

- Kikongo (Ladi, Kongo Boko, etc.) :

- Pool;

- Kikongo (Yombe, Vili, Ladi, Sundi, etc.) and Kituba :

- South-west of Democratic Republic of the Congo :

- Kikongo (Yombe, Ntandu, Ndibu, Manyanga, etc.) and Kikongo ya Leta :

- Kongo Central,

- a part of Kinshasa,

- Kikongo ya Leta :

- Kwilu,

- Kwango,

- Mai-Ndombe,

- far west Kasaï ;

- Kikongo (Yombe, Ntandu, Ndibu, Manyanga, etc.) and Kikongo ya Leta :

- North of Angola :

- Kikongo (Kisikongo, Zombo, Ibinda, etc.) :

- Cabinda,

- Uíge,

- Zaire,

- north of Bengo and north of Cuanza Norte;

- Kikongo (Kisikongo, Zombo, Ibinda, etc.) :

- South-West of Gabon.

Presence in the Americas

Many African slaves transported in the Atlantic slave trade spoke Kikongo. Its influence can be seen in many creole languages in the diaspora, such as:

- Brazil

- Colombia

- Cuba

- Habla Congo/Habla Bantu

- None; liturgical language of the Afro-Cuban Palo religion.

- Habla Congo/Habla Bantu

- Haiti

- Haitian Creole

- Langaj

- None; liturgical language of the Haitian Vodou religion.

- Suriname

People

Prior to the Berlin Conference, the people called themselves "Bisi Kongo" (plural) and "Mwisi Kongo" (singular). Today they call themselves "Bakongo" (pl.) and "Mukongo" (sing.).[9]

Writing

Kongo was the earliest Bantu language to be written in Latin characters. Portuguese created a dictionary in Kongo, the first of any Bantu language. A catechism was produced under the authority of Diogo Gomes, who was born in 1557 in Kongo to Portuguese parents and became a Jesuit priest. No version of that survives today.

In 1624, Mateus Cardoso, another Portuguese Jesuit, edited and published a Kongo translation of the Portuguese catechism compiled by Marcos Jorge. The preface says that the translation was done by Kongo teachers from São Salvador (modern Mbanza Kongo) and was probably partially the work of Félix do Espírito Santo (also a Kongo).[10]

The dictionary was written in about 1648 for the use of Capuchin missionaries. The principal author was Manuel Robredo, a secular priest from Kongo (after he became a Capuchin, he was named Francisco de São Salvador). The back of this dictionary includes a two-page sermon written in Kongo. The dictionary has some 10,000 words.

In the 1780s, French Catholic missionaries to the Loango coast created additional dictionaries. Bernardo da Canecattim published a word list in 1805.

Baptist missionaries who arrived in Kongo in 1879 (from Great Britain) developed a modern orthography of the language.

American missionary W. Holman Bentley arranged for his Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language to be published by the University of Michigan in 1887. In the preface, Bentley gave credit to Nlemvo, an African, for his assistance. He described "the methods he used to compile the dictionary, which included sorting and correcting 25,000 slips of paper containing words and their definitions."[11] Eventually W. Holman Bentley, with the special assistance of João Lemvo, produced a complete Christian Bible in 1905.

The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has published a translation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Fiote.

Standardisation

The work of English, Swedish and other missionaries in the 19th and 20th centuries, in collaboration with Kongo linguists and evangelists such as Ndo Nzuawu Nlemvo (or Ndo Nzwawu Nlemvo; Dom João in Portuguese) and Miguel NeKaka, marked the standardisation of Kikongo.[12][13][14][15]

A large proportion of the people at San Salvador, and in its neighbourhood, pronounce s and z before i as sh and j; for the sound sh, the letter x was adopted (as in Portuguese), while z before i was written as j. Our books are read over a much wider area than the district of San Salvador, and in those parts where s and z remain unchanged before i, the use of x and j has proved a difficulty; it has therefore been decided to use s and z only, and in those parts where the sound of these letters is softened before i they will be naturally softened in pronunciation, and where they remain unchanged they will be pronounced as written.

— William Holman Bentley, Dictionary and grammar of the Kongo language as spoken at San Salvador, the ancient capital of the old Kongo Empire (1887)

Linguistic classification

Kikongo belongs to the Bantu language family.

According to Malcolm Guthrie, Kikongo is in the language group H10, the Kongo languages. Other languages in the same group include Bembe (H11). Ethnologue 16 counts Ndingi (H14) and Mboka (H15) as dialects of Kongo, though it acknowledges they may be distinct languages.

Bastin, Coupez and Man's classification of the language (as Tervuren) is more recent and precise than that of Guthrie on Kikongo. The former say the language has the following dialects:

- Kikongo group H16

- Southern Kikongo H16a

- Central Kikongo H16b

- Yombe (also called Kiyombe) H16c[16]

- Fiote H16d

- Western Kikongo H16d

- Bwende H16e

- Lari H16f

- Eastern Kikongo H16g

- Southeastern Kikongo H16h

NB:[17][18][19] Kisikongo is not the protolanguage of the Kongo language cluster. Not all varieties of Kikongo are mutually intelligible (for example, 1. Civili is better understood by Kiyombe- and Iwoyo-speakers than by Kisikongo- or Kimanianga-speakers; 2. Kimanianga is better understood by Kikongo of Boko and Kintandu-speakers than by Civili or Iwoyo-speakers).

Phonology

| Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m /m/ | n /n/ | ng /ŋ/ | |

| Plosive | voiceless | p /p/ | t /t/ | k /k/ |

| prenasal voiceless | mp /ᵐp/ | nt /ⁿt/ | nk /ᵑk/ | |

| voiced | b /b/ | d /d/ | (g /ɡ/)1 | |

| prenasal voiced | mb /ᵐb/ | nd /ⁿd/ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f /f/ | s /s/ | |

| prenasal voiceless | mf /ᶬf/ | ns /ⁿs/ | ||

| voiced | v /v/ | z /z/ | ||

| prenasal voiced | mv /ᶬv/ | nz /ⁿz/ | ||

| Approximant | w /w/ | l /l/ | y /j/ | |

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| High | i /i/ | u /u/ |

| Mid | e /e/ | o /o/ |

| Low | a /a/ | |

- The phoneme /ɡ/ can occur, but is rarely used.

There is contrastive vowel length. /m/ and /n/ also have syllabic variants, which contrast with prenasalized consonants.

Grammar

Noun classes

Kikongo has a system of 18 noun classes in which nouns are classified according to noun prefixes. Most of the classes go in pairs (singular and plural) except for the locative and infinitive classes which do not admit plurals.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32]

| Classes | Noun prefixes | Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | mu-, n- | humans | muntu/muuntu/mutu/muutu (person, human) |

| 2 | ba-, wa-, a- | plural form of the class 1... | bantu/baantu/batu/baatu/wantu/antu (people, humans,) |

| 3 | mu-, n- | various: plants, inanimate... | muti/nti (tree), nlangu (water) |

| 4 | mi-, n-, i- | plural form of the class 3... | miti/minti/inti (trees), milangu/minlangu (waters) |

| 5 | di-, li- | various: body parts, vegetables... | didezo/lideso/lidezu/didezu (bean) |

| 6 | ma- | various : liquids, plural form of the class 5... | madezo/medeso/madeso/madezu (beans), maza/maamba/mamba/maampa/masi/masa (water) |

| 7 | ki-, ci (tchi/tshi) -, tsi (ti) -, i- | various: language, inanimate... | kikongo/cikongo/tsikongo/ikongo (kongo language), kikuku/cikuuku/tsikûku (kitchen) |

| 8 | bi-, i-, yi-, u- | plural form of the class 7... | bikuku/bikuuku/bikûku (kitchens) |

| 9 | Ø-, n-, m-, yi-, i- | various: animals, pets, artefacts... | nzo/nso (house), ngulu (pig) |

| 10 | Ø-, n-, m-, si-, zi-, tsi- | plural form of the classes 9, 11... | si nzo/zi nzo/zinzo/tsi nso (houses), si ngulu/zi ngulu/zingulu (pigs) |

| 11 | lu- | various: animals, artefacts, sites, attitudes, qualities, feeling... | lulendo (pride), lupangu/lupaangu (plot of land) |

| 13 | tu- | plural form of the classes 7 11... | tupangu/tupaangu (plots of land) |

| 14 | bu-, wu- | various: artefacts, sites, attitudes, qualities... | bumolo/bubolo (laziness) |

| 15 | ku-, u- | infinitives | kutuba/kutub'/utuba (to speak), kutanga/kutaangë/utanga (to read) |

| 15a | ku- | body parts... | kulu (foot), koko/kooko (hand) |

| 6 | ma- | plural form of the class 15a... | malu (foots), moko/mooko (hands) |

| 4 | mi- | plural form of the class 15a... | miooko/mioko(hands) |

| 16 | va-, ga- (ha-), fa- | locatives (proximal, exact) | va nzo (near the house), fa (on, over), ga/ha (on), va (on) |

| 17 | ku- | locatives (distal, approximate) | ku vata (in the village), kuna (over there) |

| 18 | mu- | locatives (interior) | mu nzo (in the house) |

| 19 | fi-, mua/mwa- | diminutives | fi nzo (small house), fi nuni (nestling, fledgling, little bird), mua (or mwa) nuni (nestling, fledgling, little bird) |

NB: Noun prefixes may or may not change from one Kikongo variant to another (e.g. class 7: the noun prefix ci is used in civili, iwoyo or ciladi (lari) and the noun prefix ki is used in kisikongo, kiyombe, kizombo, kimanianga,...).

Conjugation

| Personal pronouns | Translation |

|---|---|

| Mono | I |

| Ngeye | You |

| Yandi | He or she |

| Kima | It (for an object / an animal / a thing, examples: a table, a knife,...) |

| Yeto / Beto | We |

| Yeno / Beno | You |

| Yawu / Bawu (or Bau) | They |

| Bima | They (for objects / animals / things, examples: tables, knives,...) |

NB: Not all variants of Kikongo have completely the same personal pronouns and when conjugating verbs, the personal pronouns become stressed pronouns (see below and/or the references posted).

Conjugating the verb (mpanga in Kikongo) to be (kuena or kuwena; also kuba or kukala in Kikongo) in the present:[33]

| (Mono) ngiena / Mono ngina | (Me), I am |

| (Ngeye) wena / Ngeye wina / wuna / una | (You), you are |

| (Yandi) wena / Yandi kena / wuna / una | (Him / Her), he or she is |

| (Kima) kiena | (It), it is (for an object / an animal / a thing, examples: a table, a knife,...) |

| (Beto) tuena / Yeto tuina / tuna | (Us), we are |

| (Beno) luena / Yeno luina / luna | (You), you are |

| (Bawu) bena / Yawu bena | (Them), they are |

| (Bima) biena | (Them), they are (for objects / animals / things, examples: tables, knives,...) |

Conjugating the verb (mpanga in Kikongo) to have (kuvua in Kikongo; also kuba na or kukala ye) in the present :

| (Mono) mvuidi | (Me), I have |

| (Ngeye) vuidi | (You), you have |

| (Yandi) vuidi | (Him / Her), he or she has |

| (Beto) tuvuidi | (Us), we have |

| (Beno) luvuidi | (You), you have |

| (Bawu) bavuidi | (Them), they have |

NB: In Kikongo, the conjugation of a tense to different persons is done by changing verbal prefixes (highlighted in bold). These verbal prefixes are also personal pronouns. However, not all variants of Kikongo have completely the same verbal prefixes and the same verbs (cf. the references posted). The ksludotique site uses several variants of Kikongo (kimanianga,...).

Vocabulary

| Word | Translation |

|---|---|

| kiambote, yenge (kiaku, kieno) / mbot'aku / mbotieno (mboti'eno) / mbote zeno / mbote / mboti / mboto / bueke / buekanu [34] | hello, good morning |

| malafu, malavu | alcoholic drink |

| diamba | hemp |

| binkutu, binkuti | clothes |

| ntoto, mutoto | soil, floor, ground, Earth |

| nsi, tsi, si | country, province, region |

| vata, gata, divata, digata, dihata, diɣata, buala (or bwala), bual' (or bwal', bualë, bwalë), bula, hata, ɣata | village |

| mavata, magata, mahata, maɣata, mala, maala | villages |

| nzo | house |

| zulu, yulu, yilu | sky, top, above |

| maza, masa, mamba, masi, nlangu, mazi, maampa | water |

| tiya, mbasu, mbawu | fire |

| makaya | leaves (example : hemp leaves) |

| bakala, yakala | man, husband |

| nkento, mukento, nkiento, ncyento, nciento, ntchiento, ntchientu, ntchetu, ntcheetu, ncetu, nceetu, mukietu, mukeetu, mukeeto | woman |

| mukazi, nkazi, nkasi, mukasi | spouse (wife) |

| mulumi, nlumi, nnuni | spouse (husband) |

| muana (or mwana) ndumba, ndumba | young girl, single young woman |

| nkumbu / zina / li zina / dizina / ligina [35] | name |

| kudia, kudya, kulia, kulya | to eat |

| kunua, kunwa | to drink |

| nene | big |

| fioti | small |

| mpimpa | night |

| lumbu | day |

| kukovola, kukofola, kukofula, kukôla, kukosula | to cough |

| kuvana, kugana, kuhana, kuɣana | to give |

| nzola, zola | love |

| luzolo, luzolu | love, will |

| kutanga, kutaangë | to read |

| kusoneka, kusonikë, kusonika, kutina | to write |

| kuvova, kuta, kuzonza, kutuba, kutub', kugoga, kuɣoɣa, kuhoha, utuba | to say, to speak, to talk, to tell |

| kuzola, kutsolo, kuzolo, uzola | to love |

| ntangu | time, sun, hour |

| kuseva, kusega, kuseɣa, kuseha, kusefa, kusefë, kuseya | to laugh |

| nzambi | god |

| luzitu | the respect |

| lufua, lufwa | the death |

| yi ku zolele / i ku zolele [36] / ngeye nzolele / ni ku zololo (or ni ku zolele) (Ladi) / minu i ku zoleze (Ibinda) / mi ya ku zola (Vili) / minu i ku tidi (Cabindan Yombe) / mê nge nzololo (or mê nge nzolele) (Ladi) / minu i ku zoleze (Cabindan Woyo) / minu i ba ku zola (Linji, Linge) / mi be ku zol' (or mi be ku zolë) (Vili) / me ni ku tiri (Beembe) / minu i ku tili | i love you |

| Days of the week in English | Kisikongo and Kizombo | Congolese Yombe Yombe | Ladi (Lari) | Vili[37] | Ibinda | Ntandu | Kisingombe and Kimanianga |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | Kyamosi | Un'tône | Buduka / Nsila (N'sila) / M'tsila | Un'tône | Tchikunda | Kintete | Kiamonde / Kiantete |

| Tuesday | Kyazole | N'silu | Nkênge | N'silu | Tchimuali / Tchimwali | Kinzole | Kianzole |

| Wednesday | Kyatatu | Un'duka | Mpika | Un'duk | Tchintatu | Kintatu | Kiantatu |

| Thursday | Kyaya | N'sone | Nkôyi | N'sone | Tchinna | Kinya | Kianya |

| Friday | Kyatanu | Bukonzu | Bukônzo | Bukonz' | Tchintanu | Kintanu | Kiantanu |

| Saturday | Kyasabala | Sab'l | Saba / Sabala | Sab'l | Tchisabala | Sabala | Kiasabala |

| Sunday | Kyalumingu | Lumingu | Lumîngu / Nsona | Lumingu | Tchilumingu | Lumingu | Kialumingu |

| Numbers 1 to 10 in English | Kisikongo and Kizombo | Ladi (Lari) | Ntandu | Solongo | Yombe | Beembe | Vili | Kisingombe and Kimanianga | Ibinda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | Mosi | Mosi | Mosi | Mosi / Kosi | Mosi | Mosi | Muek' / Mesi | Mosi | Mueka / Tchimueka |

| Two | Zole | Zole | Zole | Zole | Wadi | Boolo / Biole | Wali | Zole | Wali |

| Three | Tatu | Tatu | Tatu | Tatu | Tatu | Tatu / Bitatu | Tatu | Tatu | Tatu |

| Four | Ya | Ya | Ya | Ya | Ya | Na / Bina | Na | Ya | Na |

| Five | Tanu | Tanu | Tanu | Tanu | Tanu | Taanu / Bitane | Tanu | Tanu | Tanu |

| Six | Sambanu | Sambanu | Sambanu | Nsambanu / Sambanu | Sambanu | Saambanu / Saamunu / Samne | Samunu | Sambanu | Sambanu |

| Seven | Nsambuadi (Nsambwadi) / Nsambuadia (Nsambwadia) | Nsambuadi (Nsambwadi) | Sambuadi (Sambwadi) | Nsambuadi (Nsambwadi) / Sambuadi (Sambwadi) | Tsambuadi (Tsambwadi) | Tsambe | Sambuali (Sambwali) | Nsambuadi (Nsambwadi) / Nsambodia | Sambuali (Sambwali) |

| Eight | Nana | Nana / Mpoomo / Mpuomô | Nana | Nana | Dinana | Mpoomo | Nana | Nana | Nana |

| Nine | Vua (Vwa) / Vue (Vwe) | Vua (Vwa) | Vua (Vwa) | Vua (Vwa) | Divua (Divwa) | Wa | Vua (Vwa) | Vua (Vwa) | Vua (Vwa) |

| Ten | Kumi | Kumi | Kumi / Kumi dimosi | Kumi | Dikumi | Kumi | Kumi | Kumi | Kumi |

English words of Kongo origin

- The Southern American English word "goober", meaning peanut, comes from Kongo nguba.[38]

- The word zombie.

- The word funk, or funky, in American popular music has its origin, some say, in the Kongo word Lu-fuki.[39]

- The name of the Cuban dance mambo comes from a Bantu word meaning "conversation with the gods".

In addition, the roller coaster Kumba at Busch Gardens Tampa Bay in Tampa, Florida gets its name from the Kongo word for "roar".

- The word chimpanzee

Sample text

According to Filomão CUBOLA, article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Fiote translates to:

- Bizingi bioso bisiwu ti batu bambutukanga mu kidedi ki buzitu ayi kibumswa. Bizingi-bene, batu, badi diela ayi tsi-ntima, bafwene kuzingila mbatzi-na-mbatzi-yandi mu mtima bukhomba.

- "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."[40]

References

External links

- Bentley, William Holman (1887). Dictionary and grammar of the Kongo language, as spoken at San Salvador, the ancient capital of the old Kongo empire, West Africa. Appendix. London Baptist Missionary Society. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- Congo kiKongo Bible : Genesis. Westlind UBS. 1992. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- OLAC resources in and about the Koongo language Archived 2014-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

Kongo learning materials

- Cours de KIKONGO (1955) (French and Kongo language) par Léon DEREAU. Maison d'éditions AD. WESMAEL-CHARLIER, Namur; 117 pages.

- Leçons de Kikongo par des Bakongo (1964) Eengenhoven - Louvain. Grammaire et Vocabulaire. 62 pages.

- KIKONGO, Notions grammaticales, Vocabulaire Français – Kikongo – Néerlandais - Latin (1960) par A. Coene, Imprimerie Mission Catholique Tumba. 102 pages.

- (1957) par Léon DEREAU, d'après le dictionnaire de K. E. LAMAN. Maison d'éditions AD. WESMAEL-CHARLIER, Namur. 60 pages.

- Carter, Hazel and João Makoondekwa. , c1987. Kongo language course : a course in the dialect of Zoombo, northern Angola = Maloòngi makíkoongo. Madison, WI : African Studies Program, University of Wisconsin—Madison.

- Nominalisations en Kisikóngó (H16): les substantifs prédicatifs et les verbes-supports vánga, sala, sá et tá (faire) (2015). Luntadila Nlandu Inocente.

- Grammaire du Kiyombe par R. P. L. DE CLERCQ. Edition Goemaere - Bruxelles - Kinshasa. 47 pages

- Nkutama a Mvila za Makanda, Imprimerie Mission Catholique Tumba, (1934) par J. CUVELIER, Vic. Apostlique de Matadi. 56 pages (L'auteur est en réalité Mwene Petelo BOKA, Catechiste redemptoriste à Vungu, originaire de Kionzo.)

- Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language (1886) Bentley, William Holman. 718 pages.

- Learn basic Kikongo (Mofeko) Omotola Akindipe and Moisés Kudimuena.

- Leçons de kikongo (kintandu) par des Bakongo. (1964) Eegenhoven - Louvain. 61 pages or Leçons de kintandu par des Bakongo. (1964) Eegenhoven - Louvain. 61 pages