The mass media in Azerbaijan refers to mass media outlets based in the Republic of Azerbaijan. Television, magazines, and newspapers are all operated by both state-owned and for-profit corporations which depend on advertising, subscription, and other sales-related revenues.

History

The History of Azerbaijani media and press has several stages:[1] the press published under tsar Russian rule which starts from 1832 and lasts until 1917, the press during the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic which covers 1918–1920, the press during the Soviet Union from 1920 to 1991, emigration press, and the press since independence to the present day.[2]

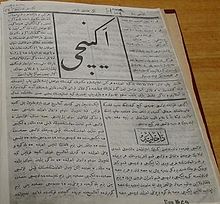

The history of the first Azerbaijani media dates back to 1875 when "Akinchi" ("Əkinçi" in the original, meaning "Cultivator", "Farmworker") was first published by Hasan Bey Zardabi.[3] The peculiarity of the journal was that it was the first ever published media in Azerbaijani.[4][5] Azerbaijani people have struggled a lot to have their national press, mainly because in late 19th century the cultural relations between states grew significantly in parallel with economic and political relations. As a consequence, educated people of Azerbaijan were remarkably influenced by circumstances going on at the time in Russia, Iran, and somewhat European countries and were encouraged to establish a local and national newspaper to express what was going on in the country. This, however, was not an easy task: Azerbaijan was under Russian control and the oppression was stricter than ever so it was hard to reflect the circumstances happening at the time due to censorship. Hasan Bey Zardabi and his colleagues chose a different path to deal with the problem: they used a very simple language peculiar to working class and mainly satire to avoid censorship.[5] The main goal of the journal, however, was completely different. Hasan Bey said in one of the issues of the journal that "the press in the region should be as a mirror".[6] Due to Russian pressure "Akinchi" had to stop publishing and it had overall 56 issues during those two years from 22 July 1875 to 29 September 1877. It was published twice a month with the circulation ranging from 300 to 400.

The second stage in the development of the national press is the press during Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan. The government during that period adopted rules about the modernization of the press and printed media in general. For example, with the new rule adopted on October 30, 1919, the establishment of press, lithography and other similar foundations, in addition, the publishing and the sale of press materials became free. The newly established government issued a decree on November 9, 1918, abolishing the government control over mass media. Approximately 100 newspapers and journals were published in Azerbaijani, Russian, Georgian, Jewish, Polish and Persian at the time. The main examples of the press of the time are "Molla Nəsrəddin", "İstiqlal", "Azərbaycan", "Açıq söz", "İqbal", "Dirilik", "Təkamül", "Mədəniyyət", "Qurtuluş" which were the forerunners of nationalist ideas.[7]

When "Iskra" published in December 1900, the new type of press was established in Azerbaijan. It was the first newspaper created to spread bolshevik ideas in Azerbaijan. in October 1904, the first-ever social-democratic press "Hummat" was secretly published in Azerbaijani language with a group of social-democrats including Mammad Amin Rasulzadeh, Meshadi Azizbekov, Nariman Narimanov, Sultan Majid Afandiyev, Prokofy Dzhaparidze.

Legislative framework

The legislative framework on freedom of speech and access to information include the Constitution of Azerbaijan, the Mass Media Law, and the Law on the Right to Obtain Information.

The norms on access to information (as well as others) have been amended after 2012. The amendments allow for-profit companies to withhold information on their registration, ownership, and structure, thus limiting the identification of the assets of politicians and public figures for privacy reasons.

Defamation remains a criminal offense in Azerbaijan and may be punished with large fines and up to 3 years in jail. "Disseminating information that damages the honor and dignity of the president" is a criminal offense (Article 106 of the Constitution and Article 323 of the Criminal Code), punishable by up to two years of prison - which may rise to five if in conjunction with other criminal charges. Since 2013, defamation laws apply to online contents too. The Azerbaijan Supreme Court has suggested that the norms on defamation are amended to be brought in line with ECHR standards.[8]

Media outlets

Print and broadcast media in Azerbaijan are mostly state-owned or subsidized by the government. Ownership opacity is backed by law. Azerbaijan hosts 9 national TV stations (of which a public service broadcaster and 3 more state-run channels), over 12 regional TV stations, 25 radio channels, over 30 daily newspapers.[9]

Print media

There are 3500 publication titles formally registered in Azerbaijan. The vast majority of them are published in Azerbaijani. The remaining 130 are published in Russian (70), English[10](50) and other languages (Turkish, French, German, Arabic, Persian, Armenian, etc.).[11]

Registered daily newspapers are more than 30. The most widely read are the critical Yeni Müsavat (qəzet) and Azadliq papers. In May 2014 Zerkalo gave up on print publications due to financial losses. Azerbaijani newspapers can be split into more serious-minded newspapers, usually referred to as broadsheets due to their large size, and sometimes known collectively as "the quality press".[12]

Radio broadcasting

As of 2014, Azerbaijan has 9 AM stations, 17 FM stations, and one shortwave station. Additionally, there are approximately 4,350,000 radios in existence.[9] Primary network provider is the Ministry of Communications and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan (MCIT). According to MCIT, the FM radio penetration rate is 97% according to 2014 data.[13]

Television broadcasting

There are three state-owned television channels: AzTV, Idman TV and Medeniyyet TV. One public channel and 6 private channels: Ictimai Television, ANS TV, Space TV, Lider TV, Azad Azerbaijan TV, Xazar TV and Region TV.[9]

Azerbaijan has a total of 47 television channels, of which 4 are public television channels and 43 are private television channels of which 12 are national television channels and 31 regional television channels. According to the Ministry of Communications and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan (MCIT), the television penetration rate is 99% according to 2014 data.[13] The penetration rate of cable television in Azerbaijan totaled 28.1% of households in 2013, from a study by the State Statistical Committee of the Azerbaijan Republic. Almost 39% of the cable television subscriber base is concentrated in major cities. The penetration rate is 59.1% in the city of Baku.[14]

From 2010 to 2014, the Institute for Reporters' Freedom and Safety (IRFS) produced Obyektiv TV, an online news channel with daily coverage on freedom of expression and human rights.

Cinema

The film industry in Azerbaijan dates back to 1898. In fact, Azerbaijan was among the first countries involved in cinematography.[15] Therefore, it's not surprising that this apparatus soon showed up in Baku – at the start of the 20th century, this bay town on the Caspian was producing more than 50 percent of the world's supply of oil. Just like today, the oil industry attracted foreigners eager to invest and to work.[16]

In 1919, during the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, a documentary The Celebration of the Anniversary of Azerbaijani Independence was filmed on Azerbaijan's independence day, 28 May, and premiered in June 1919 at several theatres in Baku.[17] After the Soviet power was established in 1920, Nariman Narimanov, Chairman of the Revolutionary Committee of Azerbaijan, signed a decree nationalizing Azerbaijan's cinema. This also influenced the creation of Azerbaijani animation.[17]

In 1991, after Azerbaijan gained its independence from the Soviet Union, the first Baku International Film Festival East-West was held in Baku. In December 2000, the former President of Azerbaijan, Heydar Aliyev, signed a decree proclaiming 2 August to be the professional holiday of filmmakers of Azerbaijan. Today Azerbaijani filmmakers are again dealing with issues similar to those faced by cinematographers prior to the establishment of the Soviet Union in 1920. Once again, both choice of content and sponsorship of films are largely left up to the initiative of the filmmaker.[15]

Telecommunications

The Azerbaijan economy has been markedly stronger in recent years and, not surprisingly, the country has been making progress in developing ICT sector. Nonetheless, it still faces problems. These include poor infrastructure and an immature telecom regulatory regime. The Ministry of Communications and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan (MCIT), as well as being an operator through its role in Aztelekom, is both a policy-maker and regulator.[13][18]

Internet

61% of the population of Azerbaijan had access to the internet in 2014, although this is mainly concentrated in Baku and other cities. Social networks as Facebook and Twitter are common and are used to share information and point of views.[19]

Media Organisations

Media agencies

Azerbaijan's main media watchdogs were the Institute for Reporters' Freedom and Safety (IRFS) and the Media Rights Institute (MRI).

The International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX), an international NGO working to reinforce independent media in Azerbaijan.

Trade unions

Regulatory authorities

Since the dissolution of the Ministry of Mass Media and Information, media regulation is carried out by two governing bodies. Azerbaijan Press Council (APC) is the self-regulatory authority of print media in the country. The National Television and Radio Council (NTRC) is the electronic media regulator of Azerbaijan. Its 9 members are appointed by the government, without limited terms (only 7 of them were active in 2014).