Picard (/ˈpɪkɑːrd/,[4] also US: /pɪˈkɑːrd, ˈpɪkərd/,[5][6] French: [pikaʁ] ⓘ) is a langue d'oïl of the Romance language family spoken in the northernmost of France and parts of Hainaut province in Belgium. Administratively, this area is divided between the French Hauts-de-France region and the Belgian Wallonia along the border between both countries due to its traditional core being the districts of Tournai and Mons (Walloon Picardy).

| Picard | |

|---|---|

| picard | |

| Pronunciation | [pikaʁ] |

| Native to | France, Belgium |

Native speakers | 700,000 (2011)[1] |

Early forms | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | None |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | pcd |

| Glottolog | pica1241 |

| ELP | Picard |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-he |

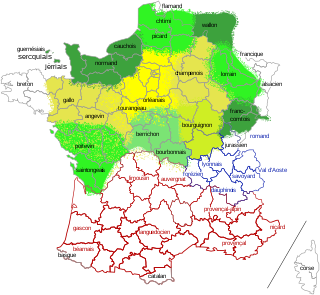

The geographical spread of Picard and Chtimi among the Oïl languages (other than French) can be seen in shades of green and yellow on this map. | |

Picard is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger [3] | |

The language or dialect is referred to by different names, as residents of Picardy call it simply Picard, but in the more populated region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais it is called Ch'ti or Ch'timi (sometimes written as Chti or Chtimi). This is the area that makes up Romance Flanders, around the metropolis of Lille and Douai, and northeast Artois around Béthune and Lens. Picard is also named Rouchi around Valenciennes, Roubaignot around Roubaix, or simply patois in general French.

In 1998, Picard native speakers amounted to 700,000 individuals, the vast majority of whom were elderly people (aged 65 and over).[7] Since its daily use had drastically declined, Picard was declared by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) a "severely endangered language".[8] However, as of 2023, the Picard language was listed as “vulnerable” by UNESCO.[9]

Origin of the word ch'ti

The word ch'ti, chtimi or ch'timi to designate the Picard language was invented during the First World War by Poilus from non-Picard speaking areas to refer to their brothers in arms from Picardy and Nord-Pas-de-Calais. It is an onomatopeia created based on the frequent use of the /ʃ/ (ch-) phoneme and of the /ʃti/ (chti) sound in Picard: "ch'ti" means the one, as in the sentence "ch'est chti qui a fait cha" ( he is the one who has done that), for instance.[10]

Recognition

Belgium's French Community gave full official recognition to Picard as a regional language along with Walloon, Gaumais (Lorraine), Champenois (Champagne) and Lorraine German in its 1990 decree. The French government has not followed suit and has not recognized Picard as an official regional language (in line with its policy of linguistic unity, which allows for only one official language in France, as per the French Constitution), but some reports have recognized Picard as a language distinct from French.

A 1999 report by Bernard Cerquiglini, the director of the Institut national de la langue française (National Institute of the French Language) stated:

The gap has continued to widen between French and the varieties of langues d'oïl, which today we would call "French dialects"; Franc-comtois, Walloon, Picard, Norman, Gallo, Poitevin, Saintongeais, Bourguignon-morvandiau, Lorrain must be accepted among the regional languages of France; by placing them on the list [of French regional languages], they will be known from then on as langues d'oïl.[11]

Even if it has no official status as a language in France, Picard, along with all the other languages spoken in France, benefits from actions led by the Culture Minister's General Delegation for the French language and the languages of France (la Délégation générale à la langue française et aux langues de France).

Origins

Picard, like French, is one of the langues d'oïl and belongs to the Gallo-Roman family of languages. It consists of all the varieties used for writing (Latin: scriptae) in the north of France from before 1000 (in the south of France at that time the Occitan language was used). Often, the langues d'oïl are referred to simply as Old French.Picard is phonetically quite different from the North-central langues d'oïl, which evolved into modern French. Among the most notable traits, the evolution in Picard towards palatalization is less marked than in the central langues d'oïl in which it is particularly striking; /k/ or /ɡ/ before /j/, tonic /i/ and /e/, as well as in front of tonic /a/ and /ɔ/ (from earlier *au; the open /o/ of the French porte) in central Old French but not in Picard:

- Picard keval ~ Old French cheval (horse; pronounced in Old French [tʃəˈval] rather than the modern [ʃəˈval]), from *kabal (vulgar Latin caballus): retaining the original /k/ in Picard before tonic /a/ and /ɔ/.

- Picard gambe ~ Old French jambe (leg; pronounced in Old French [ˈdʒãmbə] rather than the modern [ʒɑ̃b] – [ʒ] is the ge sound in beige), from *gambe (vulgar Latin gamba): absence of palatalization of /ɡ/ in Picard before tonic /a/ and /ɔ/.

- Picard kief ~ Old French chef (leader), from *kaf (Latin caput): less palatalization of /k/ in Picard

- Picard cherf ~ Old French cerf (stag; pronounced [tʃerf] and [tserf] respectively), from *kerf (Latin cervus): simple palatalization in Picard, palatalization then fronting in Old French[citation needed]

The effects of palatalization can be summarised as this:

- /k/ and (tonic) /y/, /i/ or /e/: Picard /tʃ/ (written ch) ~ Old French /ts/ (written c)

- /k/ and /ɡ/ + tonic /a/ or /ɔ/: Picard /k/ and /ɡ/ ~ Old French /tʃ/ and /dʒ/.

There are striking differences, such as Picard cachier ('to hunt') ~ Old French chacier, which later took the modern French form of chasser.Because of the proximity of Paris to the northernmost regions of France, French (that is, the languages that were spoken in and around Paris) greatly influenced Picard and vice versa. The closeness between Picard and French causes the former to not always be recognised as a language in its own right, but rather a "distortion of French" as it is often viewed.

Dialectal variations

Despite being geographically and syntactically affiliated according to some linguists due to their inter-comprehensible morphosyntactic features, Picard in Picardy, Ch'timi and Rouchi still intrinsically maintain conspicuous discrepancies. Picard includes a variety of very closely related dialects. It is difficult to list them all accurately in the absence of specific studies on the dialectal variations, but these varieties can probably provisionally be distinguished: [citation needed] Amiénois, Vimeu-Ponthieu, Vermandois, Thiérache, Beauvaisis, "chtimi" (Bassin Minier, Lille), dialects in other regions near Lille (Roubaix, Tourcoing, Mouscron, Comines), "rouchi" (Valenciennois) and Tournaisis, Borain, Artésien rural, Boulonnais. The varieties are defined by specific phonetic, morphological and lexical traits and sometimes by a distinctive literary tradition.

The Ch'ti language was re-popularised by the 2008 French comedy film Welcome to the Sticks (French: Bienvenue chez les Ch'tis; French pronunciation: [bjɛ̃vny ʃe le ʃti]) which broke nearly every box office record in France and earned over $245,000,000 worldwide on an 11 million euro budget.[12]

Verbs and tenses

The first person plural often appears in spoken Picard in the form of the neutral third person in; however, the written form prioritizes os (as in French, where on is used for nous). On the other hand, the spelling of conjugated verbs will depend on the pronunciation, which varies within the Picard domain. For instance southern Picard would read il étoait / étoét while northern Picard would read il étot. This is noted as variants in the following:

| TO BE : ète (être) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicative | Subjunctive | Imperative | ||||||||

| Present | Imperfect | Future | Conditional | Present | ||||||

| North | South | North | South | Variables | Variables | |||||

| I | ej su | j'éto(s) | j'étoé / étoais | ej srai | ej séro(s) | ej sroé | qu'ej soéche | qu'ej fuche / seuche | ||

| YOU | t'es | t'étos | t'étoés / étoais | tu sros | té séros | tu sroés | eq tu soéches | eq tu fuches / seuches | soéche | fus / fuche |

| HE | il est | i'étot | il étoét / étoait | i sro | i sérot | i sroét | qu'i soéche | qu'i fuche / seuche | ||

| SHE | al est | al étot | al étoét / étoait | ale sro | ale sérot | ale sroét | qu'ale soéche | qu'ale fuche / seuche | ||

| ONE | in est | in étot | in étoét / étoait | in sro | in sérot | in sroét | qu'in soéche | qu'in fuche / seuche | ||

| WE | os sonmes | os étonmes | os étoinmes | os srons | os séronmes | os sroinmes | qu'os soéïonches | qu'os fuchonches / seuchonches / sonches | soéïons | fuchons |

| YOU | os ètes | os étotes | os étoétes | os srez | os sérotes | os sroétes | qu'os soéïèches | qu'os fuchèches / seuchèches | soéïez | fuchez |

| THEY | is sont | is étotte | is étoétte / étoaitte | is sront | is sérotte | is sroétte | qu'is soéchtte | qu'is fuchtte / seuchtte | ||

| TO HAVE : avoèr (avoir) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicative | Subjunctive | Imperative | ||||||||

| Present | Imperfect | Future | Conditional | Present | ||||||

| North | South | North | South | Variables | Variables | |||||

| I | j'ai | j'ai | j'avo(s) | j'avoés / avoais | j'arai | j'érai | j'aros | j'éroé | eq j'euche | |

| YOU | t'as | t'os | t'avos | t'avoés | t'aras | t'éros | t'aros | t'éroés | eq t'euches | aïe |

| HE | i'a | il o | i'avot | il avoét | i'ara | il éro | i'arot | il éroét | qu'il euche | |

| SHE | al a | al o | al avot | al avoét | al ara | al éro | al arot | al éroét | qu'al euche | |

| ONE | in a | in o | in avot | in avoét | in ara | in éro | in arot | in éroét | qu'in euche | |

| WE | os avons | os avons | os avonmes | os avoinmes | os arons | os érons | os aronmes | os éroinmes | qu'os euchonches / aïonches | aïons |

| YOU | os avez | os avez | os avotes | os avoétes | os arez | os érez | os arotes | os éroétes | qu'os euchèches / aïèches | aïez |

| THEY | is ont | il ont | is avotte | is avoétte | is aront | is éront | is arotte | is éroétte | qu'is euhtte | |

| TO GO : s'in aler (s'en aller) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicative | Subjunctive | Imperative | ||||||||

| Present | Imperfect | Future | Conditional | Present | ||||||

| North | South | North | South | Variables | Variables | |||||

| I | j'm'in vas | ej m'in vos | j'm'in alos | ej m'in aloés / aloais | j'm'in irai | j'm'in iros | ej m'in iroé | qu'ej m'in ale | qu'ej m'in voaiche | |

| YOU | té t'in vas | tu t'in vos | té t'in alos | tu t'in aloés | tu t'in iros | té t'in iros | tu t'in iroés | qu'té t'in ale | qu'tu t'in voaiches | |

| HE | i s'in va | i s'in vo | i s'in a lot | i s'in aloét | i s'in iro | i s'in irot | i s'in iroét | qu'i s'in ale | qu'i s'in voaiche | |

| SHE | ale s'in va | ale s'in vo | ale s'in a lot | ale s'in aloét | ale s'in iro | ale s'in irot | ale s'in iroét | qu'ale s'in ale | qu'ale s'in voaiche | |

| ONE | in s'in va | in s'in vo | in s'in a lot | in s'in aloét | in s'in ira | in s'in irot | in s'in iroét | qu'in s'in ale | qu'in s'in voaiche | |

| WE | os nos in alons | os nos in alons | os nos in alonmes | os nos in aloinmes | os nos in irons | os nos in ironmes | os nos in iroinmes | qu'os nos in allotte | qu'os nos in alonches | |

| YOU | os vos in alez | os vos in alez | os vos in alotes | os vos in aloétes | vos vos in irez | os vos in irotes | os vos in iroétes | qu'os vos in allotte | qu'os vos in alèches | |

| THEY | is s'in vont | is s'in vont | is s'in alotte | is s'in aloétte | is s'in iront | is s'in irotte | is s'in iroétte | qu'is s'in allote | qu'is s'in voaichtte | |

Vocabulary

The majority of Picard words derive from Vulgar Latin.

| English | Picard | French |

|---|---|---|

| English | Inglé | Anglais |

| Hello! | Bojour ! or Bojour mes gins ! (formal) or Salut ti z’aute ! (informal) | Bonjour (lit.: Bonjour mes gens ! or Salut vous autres !) |

| Good evening! | Bonsoèr ! | Bonsoir |

| Good night! | La boinne nuit ! | Bonne nuit ! |

| Goodbye! | À s'ervir ! or À l’arvoïure ! or À t’ervir ! | Au revoir ! |

| Have a nice day! | Eune boinne jornée ! | Bonne journée ! |

| Please/if you please | Sins vos komander (formal) or Sins t' komander (informal) | S'il vous plaît (lit: sans vous commander) |

| Thank you | Merchi | Merci |

| I am sorry | Pardon or Échtchusez-mi | Pardon or Excusez-moi |

| What is your name? | Kmint qu’os vos aplez ? | Comment vous appelez-vous ? |

| How much? | Combin qu’cha coûte ? | Combien ça coute ? |

| I do not understand. | Éj n'comprinds poin. | Je ne comprends pas. |

| Yes, I understand. | Oui, j' comprinds. | Oui, je comprends. |

| Help! | À la rescousse ! | À l'aide (lit.: À la rescousse !) |

| Can you help me please? | Povez-vos m’aider, sins vos komander ? | Pouvez-vous m'aider, s'il vous plaît ? |

| Where are the toilets? | D'ousqu'il est ech tchioér ? | Où sont les toillettes ? (Slang: Où sont les chiottes ?) |

| Do you speak English? | Parlez-vos inglé ? | Parlez-vous anglais ? |

| I do not speak Picard. | Éj n’pérle poin picard. | Je ne parle pas picard. |

| I do not know. | Éj n’sais mie. | Je ne sais pas. (lit: Je ne sais moi.) |

| I know. | Éj sais. | Je sais. |

| I am thirsty. | J’ai soé. (literally, "I have thirst") | J'ai soif. |

| I am hungry. | J’ai fan. (literally, "I have hunger") | J'ai faim. |

| How are you? / How are things going? / How is everything? | Comint qu’i va ? (formal) or Cha va t’i ? | Comment vas-tu ? or Ça va ? |

| I am fine. | Cha va fin bien. | Ça va bien. |

| Sugar | Chuque | Sucre |

| Crybaby | Brayou | Pleurnicheur (lit: brailleur) |

Some phrases

Many words are very similar to French, but a large number are unique to Picard—principally terms relating to mining or farming.

Here are several typical phrases in Picard, accompanied by French and English translations:

- J'ai prins min louchet por mi aler fouir min gardin.

- J'ai pris ma bêche pour aller bêcher mon jardin.

- "I took my spade to go dig my garden."

- J'ai pris ma bêche pour aller bêcher mon jardin.

- Mi, à quate heures, j'archine eune bonne tartine.

- Moi, à quatre heures, je mange une bonne tartine.

- "At four o'clock, I eat a good snack."

- Moi, à quatre heures, je mange une bonne tartine.

- Quind un Ch'ti mi i'est à l'agonie, savez vous bin che qui li rind la vie ? I bot un d'mi. (Les Capenoules (a music group))

- Quand un gars du Nord est à l'agonie, savez-vous bien ce qui lui rend la vie ? Il boit un demi.

- "When a northerner is dying, do you know what revives him? He drinks a pint."

- Quand un gars du Nord est à l'agonie, savez-vous bien ce qui lui rend la vie ? Il boit un demi.

- Pindant l'briquet un galibot composot, assis sur un bos,

- L'air d'eune musique qu'i sifflotot

- Ch'étot tellemint bin fabriqué, qu'les mineurs lâchant leurs briquets

- Comminssotent à's'mette à'l'danser (Edmond Tanière - La polka du mineur)

- Pendant le casse-croûte un jeune mineur composa, assis sur un bout de bois

- L'air d'une musique qu'il sifflota

- C'était tellement bien fait que les mineurs, lâchant leurs casse-croûte

- Commencèrent à danser.

- "During lunch a young miner composed, seated on a piece of wood

- "The melody of a tune that he whistled

- "It was so well done that the miners, leaving their sandwiches,

- "Started to dance to it" (Edmond Tanière - La polka du mineur, "The Miner's Polka")

- I n'faut pas qu'ches glaines is cantent pus fort que ch'co.

- Il ne faut pas que les poules chantent plus fort que le coq.

- "Hens must not sing louder than the rooster" (n. b. this saying really refers to men and women rather than poultry)

- Il ne faut pas que les poules chantent plus fort que le coq.

- J' m'in vo à chlofe, lo qu'i n'passe poin d'caroche.

- Je vais au lit, là où il ne passe pas de carrosse.

- "I go to bed where no car is running."

- Je vais au lit, là où il ne passe pas de carrosse.

- Moqueu d'gins

- railleur, persifleur (lit. moqueur des gens)

- "someone who mocks or jeers at people" (compare gens, which is French for "people")

- railleur, persifleur (lit. moqueur des gens)

- Ramaseu d'sous

- personne âpre au gain (lit. ramasseur de sous)

- "a greedy person"

- personne âpre au gain (lit. ramasseur de sous)

Numerals

Cardinal numbers in Picard from 1 to 20 are as follows:

- One: un (m) / eune (f)

- Two: deus

- Three: troés

- Four: quate

- Five: chonc

- Six: sis

- Seven: sèt

- Eight: uit

- Nine: neu

- Ten: dis

- Eleven: onze

- Twelve: dousse

- Thirteen: trèsse

- Fourteen: quatore

- Fifteen: tchinse

- Sixteen: sèse

- Seventeen: dis-sèt

- Eighteen: dis-uit

- Nineteen: dis-neu

- Twenty: vint

Use

Picard is not taught in French schools (apart from a few one-off and isolated courses) and is generally only spoken among friends or family members. It has nevertheless been the object of scholarly research at universities in Lille and Amiens, as well as at Indiana University.[13] Since people are now able to move around France more easily than in past centuries, the different varieties of Picard are converging and becoming more similar. In its daily use, Picard is tending to lose its distinctive features and may be confused with regional French. At the same time, even though most Northerners can understand Picard today, fewer and fewer are able to speak it, and people who speak Picard as their first language are increasingly rare, particularly under 50.[14]

The 2008 film Welcome to the Sticks, starring comedian Dany Boon, deals with Ch'ti language and culture and the perceptions of the region by outsiders, and it was the highest-grossing French film of all time at the box office in France[15] until it was surpassed by The Intouchables.

Written Picard

Today Picard is primarily a spoken language, but in the medieval period, there is a wealth of literary texts in Picard. However, Picard was not able to compete with French and was slowly reduced to the status of a regional language.

A more recent body of Picard literature, written during the last two centuries, also exists. Modern written Picard is generally a transcription of the spoken language. For that reason, words are often spelled in a variety of different ways (in the same way that English and French were before they were standardized).

One system of spelling for Picard words is similar to that of French. It is undoubtedly the easiest for French speakers to understand but can also contribute the stereotype that Picard is only a corruption of French rather than a language in its own right.

Various spelling methods have been proposed since the 1960s to offset the disadvantage and to give Picard a visual identity that is distinct from French. There is now a consensus, at least between universities, in favor of the written form known as Feller-Carton (based on the Walloon spelling system, which was developed by Jules Feller, and adapted for Picard by Professor Fernand Carton).

Learning Picard

Picard, although primarily a spoken language, has a body of written literature: poetry, songs ("P'tit quinquin" for example), comic books, etc.

A number of dictionaries and patois guides also exist (for French speakers):

- René Debrie, Le cours de picard pour tous - Eche pikar, bèl é rade (le Picard vite et bien). Parlers de l'Amiénois. Paris, Omnivox, 1983 (+ 2 cassettes), 208p.

- Alain Dawson, Le picard de poche. Paris : Assimil, 2003, 192p.

- Alain Dawson, Le "chtimi" de poche, parler du Nord et du Pas-de-Calais. Paris : Assimil, 2002, 194p.

- Armel Depoilly (A. D. d'Dérgny), Contes éd no forni, et pi Ramintuvries (avec lexique picard-français). Abbeville : Ch'Lanchron, 1998, 150p.

- Jacques Dulphy, Ches diseux d'achteure : diries 1989. Amiens : Picardies d'Achteure, 1992, 71p. + cassette

- Gaston Vasseur, Dictionnaire des parlers picards du Vimeu (Somme), avec index français-picard (par l'équipe de Ch'Lanchron d'Abbeville). Fontenay-sous-Bois : SIDES, 1998 (rééd. augmentée), 816p. (11.800 termes)

- Gaston Vasseur, Grammaire des parlers picards du Vimeu (Somme) - morphologie, syntaxe, anthropologie et toponymie. 1996, 144p.

See also

References

Further reading

- Linguistic studies of Picard

- Villeneuve, Anne-José. 2013. (with Julie Auger) "'Chtileu qu’i m’freumereu m’bouque i n’est point coér au monne': Grammatical variation and diglossia in Picardie". Journal of French Language Studies 23,1:109-133.

- Auger, Julie. 2010. "Picard et français; La grammaire de la différence". Mario Barra-Jover (ed.), Langue française 168,4:19-34.

- Auger, Julie. 2008. (with Anne-José Villeneuve). Ne deletion in Picard and in regional French: Evidence for distinct grammars. Miriam Meyerhoff & Naomi Nagy (eds.), Social Lives in Language – Sociolinguistics and multilingual speech communities. Amsterdam: Benjamins. pp. 223–247.

- Auger, Julie. 2005. (with Brian José). “Geminates and Picard pronominal clitic allomorphy”. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 4:127-154.

- Auger, Julie. 2004. (with Brian José). “(Final) nasalization as an alternative to (final) devoicing: The case of Vimeu Picard”. In Brian José and Kenneth de Jong (eds.). Indiana University Linguistics Club Working Papers Online 4.

- Auger, Julie. 2003. “Le redoublement des sujets en picard”. Journal of French Language Studies 13,3:381-404.

- Auger, Julie. 2003. “Les pronoms clitiques sujets en picard: une analyse au confluent de la phonologie, de la morphologie et de la syntaxe”. Journal of French Language Studies 13,1:1-22.

- Auger, Julie. 2003. “The development of a literary standard: The case of Picard in Vimeu-Ponthieu, France”. In Brian D. Joseph et al. (eds.), When Languages Collide: Perspectives on Language Conflict, Language Competition, and Language Coexistence, . Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press. pp. 141–164.5

- Auger, Julie. 2003. “Pronominal clitics in Picard revisited”. In Rafael Núñez-Cedeño, Luís López, & Richard Cameron (eds.), Language Knowledge and Language Use: Selected Papers from LSRL 31. Amsterdam: Benjamins. pp. 3–20.

- Auger, Julie. 2003. “Picard parlé, picard écrit: comment s’influencent-ils l’un l’autre?”. In Jacques Landrecies & André Petit (eds.), "Le picard d’hier et d’aujourd’hui", special issue of Bien dire et bien Aprandre, 21, Centre d'Études médiévales et Dialectales, Lille 3, pp. 17–32.

- Auger, Julie. 2002. (with Jeffrey Steele) “A constraint-based analysis of intraspeaker variation: Vocalic epenthesis in Vimeu Picard”. In Teresa Satterfield, Christina Tortora, & Diana Cresti (eds.), Current Issues in Linguistic Theory: Selected Papers from the XXIXth Linguistic Symposium on the Romance Languages (LSRL), Ann Arbor 8–11 April 1999. Amsterdam: Benjamins. pp. 306–324.

- Auger, Julie. 2002. “Picard parlé, picard écrit: dans quelle mesure l’écrit représente-t-il l’oral?”. In Claus Pusch & Wolfgang Raible (eds.), Romanistische Korpuslinguistik. Korpora und gesprochene Sprache / Romance Corpus Linguistics. Corpora and Spoken Language. Tübingen: Gunter Narr. pp. 267–280. (ScriptOralia Series)

- Auger, Julie. 2001. “Phonological variation and Optimality Theory: Evidence from word-initial vowel epenthesis in Picard”. Language Variation and Change 13,3:253-303.

- Auger, Julie. 2000. “Phonology, variation, and prosodic structure: Word-final epenthesis in Vimeu Picard”. In Josep M. Fontana et al. (eds.), Proceedings of the First International Conference on Language Variation in Europe (ICLaVE). Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra. pp. 14–24.

External links

- «Même s’ils sont proches, le picard n’est pas un mauvais français» (in French) - an article about Julie Auger's linguistic research on Picard

- The Princess & Picard - an essay about Picard from Indiana University, USA

- Qu'est-ce que le Picard? (in French) - history of Picard

- Bienvenue chez les Ch'tis (in French)- a comedy about differences between northern and southern France.