Zaza or Zazaki[5] (Zazaki: Zazakî, Kirmanckî, Kirdkî, Dimilkî)[a][6] is a Northwestern Iranian language spoken primarily in eastern Turkey by the Zazas, who are commonly considered as Kurds, and in many cases identify as such.[7][8][9] The language is a part of the Zaza–Gorani language group of the northwestern group of the Iranian branch. The glossonym Zaza originated as a pejorative[10] and many Zazas call their language Dimlî.[11]

| Zaza | |

|---|---|

| Zazakî / Kirmanckî / Kirdkî / Dimilkî | |

| Native to | Turkey |

| Region | Provinces of Sivas, Tunceli, Bingöl, Erzurum, Erzincan, Elazığ, Muş, Malatya,[1] Adıyaman and Diyarbakır[1] |

| Ethnicity | Zazas |

Native speakers | 3–4 million (2009)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | zza |

| ISO 639-3 | zza – inclusive codeIndividual codes: kiu – Kirmanjki (Northern Zaza)diq – Dimli (Southern Zaza) |

| Glottolog | zaza1246 |

| ELP | Dimli |

| Linguasphere | 58-AAA-ba |

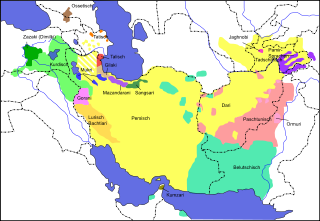

The position of Zazaki among Iranian languages[4] | |

Zaza is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

According to Ethnologue, Zaza is spoken by around three to four million people.[1] Nevins, however, puts the number of Zaza speakers between two and three million.[12] Ethnologue also states that Zaza is threatened as the language is decreasing due to losing speakers, and that many are shifting to Turkish, as well as mentioning that there are a few monolingual speakers mostly the elderly. This is causing a decline as the language is increasingly not being passed down to younger generations, with most choosing to speak Turkish. Some also speak Kurmanji.[1]

Relations to other languages

In terms of grammar, genetics, linguistics and vocabulary Zazaki is closely related to Talysh, Old Azeri, Tati, Sangsari, Semnani, Mazandarani and Gilaki languages spoken on the shores of the Caspian Sea and central Iran.[13][14] Prof. Dr. Ludwig Paul demonstrated that Zazaki is closely related to Old Azeri, Talysh and Parthian (an extinct northwestern Iranian language), shares many similarities with these languages[15] and does not have universal Kurdish vowel changes.[16] According to linguist Prof. Dr. Joyce Blau, Zazaki is a separate language and the history of Zazaki is older than that of Kurdish, some of the Zazaki and Gorani speakers have been assimilated by the Kurds, but not all.[17][18][19] Zaza is linguistically more closely related to Talysh, Tati, Semnani, Sangesari, Gilaki and the Mazandarani.[13] Due to centuries of interaction, Kurmanji has had an impact on the language, which have blurred the boundaries between the two languages.[20] This and the fact that Zaza speakers are identified as ethnic Kurds by some scholars,[21][22] has encouraged some linguists to classify the language as a Kurdish dialect.[23][24]

The formation of these consonants, which form the basis of the historical evolution of languages and the classification in language groups, is almost the same in Zazaki as in Talysh, Tati (Harzandi), Sangesari, Vafsi, and some central Iranian languages. Zazaki, here, forms a belt of northwestern Iranian languages with Talysh, Tati, central Iranian dialects and Semnani, Semnani and the Gilaki. This belt is geographically divided by speakers of Persian, Azerbaijani and Kurdish into Zazaki, Talyshi, Tati in the western part and Semnani, Sangesari, Gilaki and other Caspian/Central dialects in the eastern part. Like most other languages of the belt, Zazaki shows a two-case system in the nouns, with an oblique ending generally going back to the Old Iranian genitive ending *-ahya. Zazaki, Talyshi, Azeri, Semnani, Gilaki and some other Caspian/Central dialects derive their present stem from the same old present participle ending in *ant:[25][26][27][28]

| English | Zazaki | Semnani | Gilaki | Tati | Talyshi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "to go" | šin- | šenn- | šun- | šend- | šed- |

| "to come" | yen- | ānn- | ān- | āmānd- | omed- |

| "to say" | vān- | vān- | gān- | otn- | voted- |

| "to see" | vīnen- | ? | īn- | vīnn- | vīnd- |

| "to do" | ken- | ken- | kun- | könd- | kerded- |

| "I go" | ez šina | e šeni | men šunem | men šenden/ez mešem | ez šedam |

Zazaki, along with Tati, Talysh, and some northwestern dialects, has strongly preserved its West Iranian Proto-Indo-European consonant roots and is quite distant from Persian and Kurdish. While Zazaki, along with Talysh and Tati, remain at the westernmost part of the western Iranian languages, Persian and Kurdish are positioned at the easternmost part:[29]

| Proto Indo-European | Part | Azeri/Tati[b] | Zazaki | Talysh | Semnani | Caspian lang./dial. | Central dia. | Balochi | Kurdish | Persian |

| *ḱ/ĝ | s/z | s/z | s/z | s/z | s/z | s/z | s/z | s/z | s/z | h/d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *kue | -ž- | -ž- | -ĵ- | -ž | -ĵ, ž- | -ĵ- | -ĵ-, ž, z | -ĵ- | -ž- | -z- |

| *gue | ž | ž (y-) | ĵ | ž | ĵ,ž | ĵ | ĵ, ž, z | ĵ | ž | z |

| *kw29 | ? | isb | esb | asb | esp | s | esb | ? | s | s |

| *tr/tl | hr | (h)r | (hi)r | (h)*r | (h)r | r | r | s | s | s |

| *d(h)w | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | d | d | d |

| *rd/*rz | r/rz | r/rz | r/rz | rz | l/l(rz) | l/l | l/l(rz) | l/l | l/l | l/l |

| *sw | wx | h | w | h | x(u) | x(u) | x(u), f | v | x(w) | x(u) |

| *tw | f | u | w | h | h | h | h(u) | h | h | h |

| *y- | y | y | ĵ | ĵ | ĵ | ĵ | ĵ (y) | ĵ | ĵ | ĵ |

History

Writing in Zaza is a recent phenomenon. The first literary work in Zaza is Mewlîdu'n-Nebîyyî'l-Qureyşîyyî by Ehmedê Xasi in 1899, followed by the work Mawlûd by Osman Efendîyo Babij in 1903. As the Kurdish language was banned in Turkey during a large part of the Republican period, no text was published in Zaza until 1963. That year saw the publication of two short texts by the Kurdish newspaper Roja Newe, but the newspaper was banned and no further publication in Zaza took place until 1976, when periodicals published a few Zaza texts. Modern Zaza literature appeared for the first time in the journal Tîrêj in 1979 but the journal had to close as a result of the 1980 coup d'état. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, most Zaza literature was published in Germany, France and especially Sweden until the ban on the Kurdish language was lifted in Turkey in 1991. This meant that newspapers and journals began publishing in Zaza again. The next book to be published in Zaza (after Mawlûd in 1903) was in 1977, and two more books were published in 1981 and 1986. From 1987 to 1990, five books were published in Zaza. The publication of books in Zaza increased after the ban on the Kurdish language was lifted and a total of 43 books were published from 1991 to 2000. As of 2018, at least 332 books have been published in Zaza.[30]

Due to the above-mentioned obstacles, the standardization of Zaza could not have taken place and authors chose to write in their local or regional Zaza variety. In 1996, however, a group of Zaza-speaking authors gathered in Stockholm and established a common alphabet and orthographic rules which they published. Some authors nonetheless do not abide by these rules as they do not apply the orthographic rules in their oeuvres.[31]

In 2009, Zaza was classified as a vulnerable language by UNESCO.[32]

The institution of Higher Education of Turkey approved the opening of the Zaza Language and Literature Department in Munzur University in 2011 and began accepting students in 2012 for the department. In the following year, Bingöl University established the same department.[33] TRT Kurdî also broadcast in the language.[34] Some TV channels which broadcast in Zaza were closed after the 2016 coup d'état attempt.[35]

Dialects

There are two main Zaza dialects:

- Northern Zaza [kiu]: It is spoken in Tunceli, Erzincan, Erzurum, Sivas, Gümüşhane, Muş, and Kayseri provinces.

Its subdialects are:

- Southern Zaza [diq]: It is spoken in primarily Bingöl, Çermik, Dicle, Eğil, Gerger, Palu and Hani, Turkey.

Its subdialects are:

- Sivereki, Kori, Hazzu, Motki, Dumbuli, Eastern/Central Zazaki, Dersimki.

Zaza shows many similarities with other Northwestern Iranian languages:

- Similar personal pronouns and use of these[37]

- Enclitic use of the letter "u"[37]

- Very similar ergative structure[38]

- Masculine and feminine ezafe system[39]

- Both languages have nominative and oblique cases that differs by masculine -î and feminine -ê

- Both languages have forgotten possessive enclitics, while it exists in such other languages as Persian, Sorani, Gorani, Hewrami or Shabaki

- Both languages distinguish between aspirated and unaspirated voiceless stops

- Similar vowel phonemes

Ludwig Paul divides Zaza into three main dialects. In addition, there are transitions and edge accents that have a special position and cannot be fully included in any dialect group.[40]

Grammar

| Pronoun | Zaza | Talysh [41] | Tati[42][43] | Semnani[44] | Sangsari[45] | Ossetian[46] | Persian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st sing. | ez | āz | āz | ā | ā | æz (az) | man | I |

| 2nd | tı | te/ti | ti | ti | ti | dɨ (di) | to | you |

| 3rd | o/ey | ay | u | un | no | wuiy | ū, ān | he |

| 3rd | a/ay | - | nā | una | na | - | - | she |

| 1st plur. | ma | ama | amā | hamā | mā | max | mā | we |

| 2nd | şıma | shēma/shūma | shūmā | shūmā | shūmā | shimax | shomā | you |

| 3rd. | ê, i, ina, ino | ayēn | ē | e | ey | idon/widon | ēnan, ishān, inhā | they |

As with a number of other Iranian languages like Talysh,[47] Tati,[14][48] central Iranian languages and dialects like Semnani, Kahangi, Vafsi,[49] Balochi[50] and Kurmanji, Zaza features split ergativity in its morphology, demonstrating ergative marking in past and perfective contexts, and nominative-accusative alignment otherwise. Syntactically it is nominative-accusative.[51]

Grammatical gender

Among all Western Iranian languages Zaza, Semnani,[52][53][54] Sangsari,[55] Tati,[56][57] central Iranian dialects like Cālī, Fārzāndī, Delījanī, Jowšaqanī, Abyāne'i[58] and Kurmanji distinguish between masculine and feminine grammatical gender. Each noun belongs to one of those two genders. In order to correctly decline any noun and any modifier or other type of word affecting that noun, one must identify whether the noun is feminine or masculine. Most nouns have inherent gender. However, some nominal roots have variable gender, i.e. they may function as either masculine or feminine nouns.[59]

Phonology

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɨ | u |

| ʊ | |||

| Mid | e | ə | o |

| Open | ɑ |

The vowel /e/ may also be realized as [ɛ] when occurring before a consonant. /ɨ/ may become lowered to [ɪ] when occurring before a velarized nasal /n/ [ŋ], or occurring between a palatal approximant /j/ and a palato-alveolar fricative /ʃ/. Vowels /ɑ/, /ɨ/, or /ə/ become nasalized when occurring before /n/, as [ɑ̃], [ɨ̃], and [ə̃], respectively.

Consonants

/n/ becomes a velar [ŋ] when following a velar consonant.[60][61]

Alphabet

Zaza texts written during the Ottoman era were written in Arabic letters. The works of this era had religious content. The first Zaza text, written by Sultan Efendi, in 1798, was written in Arabic letters in the Nesih font, which was also used in Ottoman Turkish.[62] Following this work, the first Zaza language Mawlid, written by the Ottoman-Zaza cleric, writer and poet Ahmed el-Hassi in 1891-1892, was also written in Arabic letters and published in 1899.[63][64] Another Mawlid in Zaza language, written by another Ottoman-Zaza cleric Osman Esad Efendi between 1903-1906, was also written in Arabic letters.[65] After the Republic, Zazaki works began to be written in Latin letters, abandoning the Arabic alphabet. However, today Zazaki does not have a common alphabet used by all Zazas. An alphabet called the Jacabson alphabet was developed with the contributions of the American linguist C. M Jacobson and is used by the Zaza Language Institute in Frankfurt, which works on the standardization of Zaza language.[66] The Zaza alphabet, prepared by Zülfü Selcan and started to be used at Munzur University as of 2012, is another writing system developed for Zazaki, consisting of 32 letters, 8 of which are vowels and 24 of which are consonants.[67] Another alphabet used for the language is the Bedirxan alphabet. The Zaza alphabet is an extension of the Latin alphabet used for writing the Zaza language, consisting of 32 letters, six of which (ç, ğ, î, û, ş, and ê) have been modified from their Latin originals for the phonetic requirements of the language.[68]

| Upper case | A | B | C | Ç | D | E | Ê | F | G | Ğ | H | I[A] | İ/Î[A] | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | Ş | T | U | Û | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower case | a | b | c | ç | d | e | ê | f | g | ğ | h | ı/i [A] | i/î [A] | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | ş | t | u | û | v | w | x | y | z |

| IPA phonemes | a | b | d͡ʒ | t͡ʃ | d | ɛ | e | f | g | ɣ | h | ɨ | i | ʒ | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r, ɾ | s | ʃ | t | ʊ | u | v | w | x | j | z |

Gallery

References

Literature

- Arslan, İlyas (2016). Verbfunktionalität und Ergativität in der Zaza-Sprache [Verb functionality and ergativity in the Zaza language] (PDF) (PhD thesis). Universität Düsseldorf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2016.

- Blau, Joyce (1989). "Gurânî et Zâzâ". In Schmitt, Rüdiger (ed.). Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum. Wiesbaden: Reichert. pp. 336–340. ISBN 3-88226-413-6. (About Daylamite origin of Zaza-Guranis)

- Gajewski, Jon. (2004) "Zazaki Notes" Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Gippert, Jost (4 May 1996). Die historische Entwicklung der Zaza-Sprache (PDF) (Speech). Mannheim Zaza Book Festival (in German). University of Frankfurt. (not original published speech)

- Gippert, Jost (4 May 1996). Zazaca'nın tarihsel gelişimi (PDF) (Speech). Mannheim Zaza Book Festival (in Turkish). Translated by Dursun, Hasan. University of Frankfurt. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2006.

- Haig, Geoffrey; Öpengin, Ergin. "Introduction to Special Issue - Kurdish: A critical research overview" (PDF). Kurdish Studies. 2 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2014.

- Keskin, Mesut (2008). Zur dialektalen Gliederung des Zazaki (Thesis). Frankfurt am Main: Goethe-Universität.

- Larson, Richard K.; Yamakido, Hiroko (8 January 2006). Zazaki "Double Ezafe" as Double Case-Marking (PDF). LSA. Albuquerque, NM. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2006.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Todd, Terry Lynn (1985). A Grammar of Dimili (Also Known as Zaza) (Thesis). University of Michigan. hdl:2027.42/160737.

- Malmîsanij, Mehemed (2021). "The Kirmanjki (Zazaki) Dialect of Kurdish Language and the Issues it Faces". In Bozarslan, Hamit; Gunes, Cengiz; Yadirgi, Veli (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Kurds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 663–684. doi:10.1017/9781108623711.027. ISBN 978-1-108-62371-1. S2CID 235541104.

- Paul, Ludwig (1998). "The Position of Zazaki Among West Iranian languages" (PDF). In Sims-Williams, Nicholas (ed.). Proceedings of the Third European Conference of Iranian Studies held in Cambridge, 11th to 15th September 1995. Vol. I: Old and Middle Iranian Studies. Wiesbaden: Ludwig Reichert. pp. 163–177.

- Werner, Brigitte (2007). Features of Bilingualism in the Zaza Community (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2009.

See also

Further reading

- Henarek – Granatäpfelchen: Welat Şêrq ra Sonîk | Märchen aus dem Morgenland. Gesammelt und verfasst von Suphi Aydin. Hamburg: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2022. ISBN 978-3-929728-89-7.

External links

- Zaza People and Zazaki Literature

- News, Articles and Columns (in Zaza)

- News, Folktales, Grammar Course Archived 29 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in Zaza)

- News, Articles and Bingöl city (in Zaza)

- Center of Zazaki (in Zaza, German, Turkish, and English)

- Website of Zazaki Institute Frankfurt

- "Zaza a Northwestern Iranic language of eastern Turkey". Endangered Language Alliance.