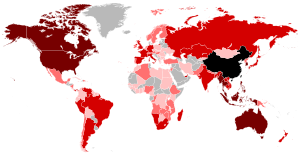

Overseas Chinese people are those of Chinese birth or ethnicity who reside outside mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau.[26] As of 2011, there were over 40.3 million overseas Chinese.[9] Overall, China has a low percent of population living overseas.

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 60,000,000[1][2][3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Thailand | 9,392,792 (2012)[4] |

| Malaysia | 6,884,800 (2022)[5] |

| United States | 5,400,000 (2019)[6] |

| Indonesia | 2,832,510 (2010)[7] |

| Singapore | 2,675,521 (2020)[8] |

| Myanmar | 1,725,794 (2011)[9] |

| Canada | 1,715,770 (2021)[10] |

| Australia | 1,390,639 (2021)[11] |

| Philippines | 1,350,000 (2013)[12] |

| South Korea | 1,070,566 (2018)[13] |

| Vietnam | 749,466 (2019)[14] |

| Japan | 744,551 (2022)[15] |

| Russia | 447,200 (2011)[9] |

| France | 441,750 (2011)[9] |

| United Kingdom | 433,150 (2011)[16] |

| Italy | 330,495 (2020)[17] |

| Brazil | 252,250 (2011)[9] |

| New Zealand | 247,770 (2018)[18] |

| Germany | 217,000 (2023)[19] |

| Laos | 176,490 (2011)[9] |

| Cambodia | 147,020 (2011)[9] |

| Spain | 140,620 (2011)[9] |

| Panama | 135,960 (2011)[9] |

| India | 200,000 (2023)[9] |

| Netherlands | 111,450 (2011)[9] |

| South Africa | 110,220–400,000 (2011)[9][20] |

| United Arab Emirates | 109,500 (2011)[9] |

| Saudi Arabia | 14,619 (2022 census) [21][22] |

| Brunei | 42,132 (2021)[23] |

| Mauritius | 26,000–39,000 |

| Reunion | 25,000 (2000) |

| Mexico | 24,489 (2019) |

| Papua New Guinea | 20,000 (2008)[24] |

| Ireland | 19,447 (2016) |

| Bangladesh | 7,500 |

| Timor Leste | 4,000-20,000 (2021) |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Chinese people | |

| Overseas Chinese | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 海外華人 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 海外华人 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 海外中國人 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 海外中国人 | ||||||

| |||||||

Terminology

Huáqiáo (simplified Chinese: 华侨; traditional Chinese: 華僑) or Hoan-kheh (Chinese: 番客; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Hoan-kheh) in Hokkien, refers to people of Chinese citizenship residing outside of either the PRC or ROC (Taiwan). The government of China realized that the overseas Chinese could be an asset, a source of foreign investment and a bridge to overseas knowledge; thus, it began to recognize the use of the term Huaqiao.[33]

Ching-Sue Kuik renders huáqiáo in English as "the Chinese sojourner" and writes that the term is "used to disseminate, reinforce, and perpetuate a monolithic and essentialist Chinese identity" by both the PRC and the ROC.[34]

The modern informal internet term haigui (simplified Chinese: 海归; traditional Chinese: 海歸) refers to returned overseas Chinese and guīqiáo qiáojuàn (simplified Chinese: 归侨侨眷; traditional Chinese: 歸僑僑眷) to their returning relatives.[35][clarification needed]

Huáyì (simplified Chinese: 华裔; traditional Chinese: 華裔; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Hôa-è) refers to people of Chinese origin residing outside of China, regardless of citizenship.[36] Another often-used term is 海外華人 (Hǎiwài Huárén) or simply 華人/华人 (Huárén) in Mandarin. It is often used by the Government of the People's Republic of China to refer to people of Chinese ethnicities who live outside the PRC, regardless of citizenship (they can become citizens of the country outside China by naturalization).

Overseas Chinese who are ethnic Han Chinese, such as Cantonese, Hokchew, Hokkien, Hakka or Teochew refer to themselves as 唐人 (Tángrén), pronounced Tòhng yàn in Cantonese, Toung ning in Hokchew, Tn̂g-lâng in Hokkien and Tong nyin in Hakka. Literally, it means Tang people, a reference to Tang dynasty China when it was ruling. This term is commonly used by the Cantonese, Hokchew, Hakka and Hokkien as a colloquial reference to the Chinese people and has little relevance to the ancient dynasty. For example, in the early 1850s when Chinese shops opened on Sacramento St. in San Francisco, California, United States, the Chinese emigrants, mainly from the Pearl River Delta west of Canton, called it Tang People Street (Chinese: 唐人街; pinyin: Tángrén Jiē)[37][38]: 13 and the settlement became known as Tang People Town (Chinese: 唐人埠; pinyin: Tángrén Bù) or Chinatown, which in Cantonese is Tong Yun Fow.[38]: 9–40

The term shǎoshù mínzú (simplified Chinese: 少数民族; traditional Chinese: 少數民族) is added to the various terms for the overseas Chinese to indicate those who would be considered ethnic minorities in China. The terms shǎoshù mínzú huáqiáo huárén and shǎoshù mínzú hǎiwài qiáobāo (simplified Chinese: 少数民族海外侨胞; traditional Chinese: 少數民族海外僑胞) are all in usage. The Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the PRC does not distinguish between Han and ethnic minority populations for official policy purposes.[35] For example, members of the Tibetan people may travel to China on passes granted to certain people of Chinese descent.[39] Various estimates of the Chinese emigrant minority population include 3.1 million (1993),[40] 3.4 million (2004),[41] 5.7 million (2001, 2010),[42][43] or approximately one tenth of all Chinese emigrants (2006, 2011).[44][45] Cross-border ethnic groups (跨境民族, kuàjìng mínzú) are not considered Chinese emigrant minorities unless they left China after the establishment of an independent state on China's border.[35]

Some ethnic groups who have historic connections with China, such as the Hmong, may not or may identify themselves as Chinese.[46]

History

The Chinese people have a long history of migrating overseas, as far back as the 10th century. One of the migrations dates back to the Ming dynasty when Zheng He (1371–1435) became the envoy of Ming. He sent people – many of them Cantonese and Hokkien – to explore and trade in the South China Sea and in the Indian Ocean.

Early emigration

In the mid-1800s, outbound migration from China increased as a result of the European colonial powers opening up treaty ports.[47]: 137 The British colonization of Hong Kong further created the opportunity for Chinese labor to be exported to plantations and mines.[47]: 137

During the era of European colonialism, many overseas Chinese were coolie laborers.[47]: 123 Chinese capitalists overseas often functioned as economic and political intermediaries between colonial rulers and colonial populations.[47]: 123

The area of Taishan, Guangdong Province was the source for many of economic migrants.[36] In the provinces of Fujian and Guangdong in China, there was a surge in emigration as a result of the poverty and village ruin.[48]

San Francisco and California was an early American destination in the mid-1800s because of the California Gold Rush. Many settled in San Francisco forming one of the earliest Chinatowns. For the countries in North America and Australia saw great numbers of Chinese gold diggers finding gold in the gold mining and railway construction. Widespread famine in Guangdong impelled many Cantonese to work in these countries to improve the living conditions of their relatives.

From 1853 until the end of the 19th century, about 18,000 Chinese were brought as indentured workers to the British West Indies, mainly to British Guiana (now Guyana), Trinidad and Jamaica.[49] Their descendants today are found among the current populations of these countries, but also among the migrant communities with Anglo-Caribbean origins residing mainly in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada.

Some overseas Chinese were sold to South America during the Punti–Hakka Clan Wars (1855–1867) in the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong.

Research conducted in 2008 by German researchers who wanted to show the correlation between economic development and height, used a small dataset of 159 male labourers from Guangdong who were sent to the Dutch colony of Suriname to illustrate their point. They stated that the Chinese labourers were between 161 to 164 cm in height for males.[50] Their study did not account for factors other than economic conditions and acknowledge the limitations of such a small sample.

The Lanfang Republic (Chinese: 蘭芳共和國; pinyin: Lánfāng Gònghéguó) in West Kalimantan was established by overseas Chinese.

In 1909, the Qing dynasty established the first Nationality Law of China.[47]: 138 It granted Chinese citizenship to anyone born to a Chinese parent.[47]: 138 It permitted dual citizenship.[47]: 138

Republic of China

In the first half of the 20th Century, war and revolution accelerated the pace of migration out of China.[47]: 127 The Kuomintang and the Communist Party competed for political support from overseas Chinese.[47]: 127–128

Under the Republicans economic growth froze and many migrated outside the Republic of China, mostly through the coastal regions via the ports of Fujian, Guangdong, Hainan and Shanghai. These migrations are considered to be among the largest in China's history. Many nationals of the Republic of China fled and settled down overseas mainly between the years 1911–1949 before the Nationalist government led by Kuomintang lost the mainland to Communist revolutionaries and relocated. Most of the nationalist and neutral refugees fled mainland China to North America while others fled to Southeast Asia (Singapore, Brunei, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and Philippines) as well as Taiwan (Republic of China).[51]

After World War II

Those who fled during 1912–1949 and settled down in Singapore and Malaysia and automatically gained citizenship in 1957 and 1963 as these countries gained independence.[52][53] Kuomintang members who settled in Malaysia and Singapore played a major role in the establishment of the Malaysian Chinese Association and their meeting hall at Sun Yat Sen Villa. There was evidence that some intended to reclaim mainland China from the CCP by funding the Kuomintang.[54][55]

After their defeat in the Chinese Civil War, parts of the Nationalist army retreated south and crossed the border into Burma as the People's Liberation Army entered Yunnan.[47]: 65 The United States supported these Nationalist forces because the United States hoped they would harass the People's Republic of China from the southwest, thereby diverting Chinese resources from the Korean War.[47]: 65 The Burmese government protested and international pressure increased.[47]: 65 Beginning in 1953, several rounds of withdrawals of the Nationalist forces and their families were carried out.[47]: 65 In 1960, joint military action by China and Burma expelled the remaining Nationalist forces from Burma, although some went on to settle in the Burma-Thailand borderlands.[47]: 65–66

During the 1950s and 1960s, the ROC tended to seek the support of overseas Chinese communities through branches of the Kuomintang based on Sun Yat-sen's use of expatriate Chinese communities to raise money for his revolution. During this period, the People's Republic of China tended to view overseas Chinese with suspicion as possible capitalist infiltrators and tended to value relationships with Southeast Asian nations as more important than gaining support of overseas Chinese, and in the Bandung declaration explicitly stated[where?] that overseas Chinese owed primary loyalty to their home nation.[dubious – discuss]

From the mid-20th century onward, emigration has been directed primarily to Western countries such as the United States, Australia, Canada, Brazil, The United Kingdom, New Zealand, Argentina and the nations of Western Europe; as well as to Peru, Panama, and to a lesser extent to Mexico. Many of these emigrants who entered Western countries were themselves overseas Chinese, particularly from the 1950s to the 1980s, a period during which the PRC placed severe restrictions on the movement of its citizens.

Due to the political dynamics of the Cold War, there was relatively little migration from the People's Republic of China to southeast Asia from the 1950s until the mid-1970s.[47]: 117

In 1984, Britain agreed to transfer the sovereignty of Hong Kong to the PRC; this triggered another wave of migration to the United Kingdom (mainly England), Australia, Canada, US, South America, Europe and other parts of the world. The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre further accelerated the migration. The wave calmed after Hong Kong's transfer of sovereignty in 1997. In addition, many citizens of Hong Kong hold citizenships or have current visas in other countries so if the need arises, they can leave Hong Kong at short notice.[citation needed]

In recent years, the People's Republic of China has built increasingly stronger ties with African nations. In 2014, author Howard French estimated that over one million Chinese have moved in the past 20 years to Africa.[56]

More recent Chinese presences have developed in Europe, where they number well over 1 million, and in Russia, they number over 200,000, concentrated in the Russian Far East. Russia's main Pacific port and naval base of Vladivostok, once closed to foreigners and belonged to China until the late 19th century, as of 2010[update] bristles with Chinese markets, restaurants and trade houses. A growing Chinese community in Germany consists of around 76,000 people as of 2010[update].[57] An estimated 15,000 to 30,000 Chinese live in Austria.[58]

Overseas Chinese experience

Commercial success

Chinese emigrants are estimated to control US$2 trillion in liquid assets and have considerable amounts of wealth to stimulate economic power in China.[59][60] The Chinese business community of Southeast Asia, known as the bamboo network, has a prominent role in the region's private sectors.[61][62]In Europe, North America and Oceania, occupations are diverse and impossible to generalize; ranging from catering to significant ranks in medicine, the arts and academia.

Overseas Chinese often send remittances back home to family members to help better them financially and socioeconomically. China ranks second after India of top remittance-receiving countries in 2018 with over US$67 billion sent.[63]

Assimilation

Overseas Chinese communities vary widely as to their degree of assimilation, their interactions with the surrounding communities (see Chinatown), and their relationship with China.

Thailand has the largest overseas Chinese community and is also the most successful case of assimilation, with many claiming Thai identity. For over 400 years, descendants of Thai Chinese have largely intermarried and/or assimilated with their compatriots. The present royal house of Thailand, the Chakri dynasty, was founded by King Rama I who himself was partly of Chinese ancestry. His predecessor, King Taksin of the Thonburi Kingdom, was the son of a Chinese immigrant from Guangdong Province and was born with a Chinese name. His mother, Lady Nok-iang (Thai: นกเอี้ยง), was Thai (and was later awarded the noble title of Somdet Krom Phra Phithak Thephamat).

In the Philippines, the Chinese, known as the Sangley, from Fujian and Guangdong were already migrating to the islands as early as 9th century, where many have largely intermarried with both native Filipinos and Spanish Filipinos (Tornatrás). Early presence of Chinatowns in overseas communities start to appear in Spanish colonial Philippines around 16th century in the form of Parians in Manila, where Chinese merchants were allowed to reside and flourish as commercial centers, thus Binondo, a historical district of Manila, has become the world's oldest Chinatown.[64] Under Spanish colonial policy of Christianization, assimilation and intermarriage, their colonial mixed descendants would eventually form the bulk of the middle class which would later rise to the Principalía and illustrado intelligentsia, which carried over and fueled the elite ruling classes of the American period and later independent Philippines. Chinese Filipinos play a considerable role in the economy of the Philippines[65][66][67][68] and descendants of Sangley compose a considerable part of the Philippine population.[68][69] Ferdinand Marcos, the former president of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos was of Chinese descent, as were many others.[70]

Myanmar shares. a long border with China so ethnic minorities of both countries have cross-border settlements. These include the Kachin, Shan, Wa, and Ta’ang.[71]

In Cambodia, between 1965 and 1993, people with Chinese names were prevented from finding governmental employment, leading to a large number of people changing their names to a local, Cambodian name. Ethnic Chinese were one of the minority groups targeted by Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge during the Cambodian genocide.[72]

Indonesia forced Chinese people to adopt Indonesian names after the Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66.[73]

In Vietnam, all Chinese names can be pronounced by Sino-Vietnamese readings. For example, the name of the previous paramount leader Hú Jǐntāo (胡錦濤) would be spelled as "Hồ Cẩm Đào" in Vietnamese. There are also great similarities between Vietnamese and Chinese traditions such as the use Lunar New Year, philosophy such as Confucianism, Taoism and ancestor worship; leads to some Hoa people adopt easily to Vietnamese culture, however many Hoa still prefer to maintain Chinese cultural background. The official census from 2009 accounted the Hoa population at some 823,000 individuals and ranked 6th in terms of its population size. 70% of the Hoa live in cities and towns, mostly in Ho Chi Minh city while the rests live in the southern provinces.[74]

On the other hand, in Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei, the ethnic Chinese have maintained a distinct communal identity.

In East Timor, a large fraction of Chinese are of Hakka descent.

In Western countries, the overseas Chinese generally use romanised versions of their Chinese names, and the use of local first names is also common.

Discrimination

Overseas Chinese have often experienced hostility and discrimination. In countries with small ethnic Chinese minorities, the economic disparity can be remarkable. For example, in 1998, ethnic Chinese made up just 1% of the population of the Philippines and 4% of the population in Indonesia, but have wide influence in the Philippine and Indonesian private economies.[75] The book World on Fire, describing the Chinese as a "market-dominant minority", notes that "Chinese market dominance and intense resentment amongst the indigenous majority is characteristic of virtually every country in Southeast Asia except Thailand and Singapore".[76]

This asymmetrical economic position has incited anti-Chinese sentiment among the poorer majorities. Sometimes the anti-Chinese attitudes turn violent, such as the 13 May Incident in Malaysia in 1969 and the Jakarta riots of May 1998 in Indonesia, in which more than 2,000 people died, mostly rioters burned to death in a shopping mall.[77]

During the Indonesian killings of 1965–66, in which more than 500,000 people died,[78] ethnic Chinese Hakkas were killed and their properties looted and burned as a result of anti-Chinese racism on the excuse that Dipa "Amat" Aidit had brought the PKI closer to China.[79][80] The anti-Chinese legislation was in the Indonesian constitution until 1998.

The state of the Chinese Cambodians during the Khmer Rouge regime has been described as "the worst disaster ever to befall any ethnic Chinese community in Southeast Asia." At the beginning of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1975, there were 425,000 ethnic Chinese in Cambodia; by the end of 1979 there were just 200,000.[81]

It is commonly held that a major point of friction is the apparent tendency of overseas Chinese to segregate themselves into a subculture.[82][failed verification] For example, the anti-Chinese Kuala Lumpur Racial Riots of 13 May 1969 and Jakarta Riots of May 1998 were believed to have been motivated by these racially biased perceptions.[83] This analysis has been questioned by some historians, notably Dr. Kua Kia Soong, who has put forward the controversial argument that the 13 May Incident was a pre-meditated attempt by sections of the ruling Malay elite to incite racial hostility in preparation for a coup.[84][85] In 2006, rioters damaged shops owned by Chinese-Tongans in Nukuʻalofa.[86] Chinese migrants were evacuated from the riot-torn Solomon Islands.[87]

Ethnic politics can be found to motivate both sides of the debate. In Malaysia, many "Bumiputra" ("native sons") Malays oppose equal or meritocratic treatment towards Chinese and Indians, fearing they would dominate too many aspects of the country.[88][89] The question of to what extent ethnic Malays, Chinese, or others are "native" to Malaysia is a sensitive political one. It is currently a taboo for Chinese politicians to raise the issue of Bumiputra protections in parliament, as this would be deemed ethnic incitement.[90]

Many of the overseas Chinese emigrants who worked on railways in North America in the 19th century suffered from racial discrimination in Canada and the United States. Although discriminatory laws have been repealed or are no longer enforced today, both countries had at one time introduced statutes that barred Chinese from entering the country, for example the United States Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (repealed 1943) or the Canadian Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 (repealed 1947). In both the United States and Canada, further acts were required to fully remove immigration restrictions (namely United States' Immigration and Nationality Acts of 1952 and 1965, in addition to Canada's)

In Australia, Chinese were targeted by a system of discriminatory laws known as the 'White Australia Policy' which was enshrined in the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901. The policy was formally abolished in 1973, and in recent years Australians of Chinese background have publicly called for an apology from the Australian Federal Government[91] similar to that given to the 'stolen generations' of indigenous people in 2007 by the then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd.

In South Korea, the relatively low social and economic statuses of ethnic Korean-Chinese have played a role in local hostility towards them.[92] Such hatred had been formed since their early settlement years, where many Chinese-Koreans hailing from rural areas were accused of misbehaviour such as spitting on streets and littering.[92] More recently, they have also been targets of hate speech for their association with violent crime,[93][94] despite the Korean Justice Ministry recording a lower crime rate for Chinese in the country compared to native South Koreans in 2010.[95]

Relationship with China

Both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China (known more commonly as Taiwan) maintain high level relationships with the overseas Chinese populations. Both maintain cabinet level ministries to deal with overseas Chinese affairs, and many local governments within the PRC have overseas Chinese bureaus.

Before 2018, the PRC's Overseas Chinese Affairs Office (OCAO) under the State Council was responsible for liaising with overseas Chinese.[47]: 132 In 2018, the office was merged into the United Front Work Department of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.[96][47]: 132

Throughout its existence but particularly during the Xi Jinping administration, the PRC makes patriotic appeals to overseas Chinese to assist the country's political and economic needs.[47]: 132 In a July 2022 meeting with the United Front Work Department, Xi encouraged overseas Chinese to support China's rejuvenation and stated that domestic and overseas Chinese should pool their strengths to realize the Chinese Dream.[47]: 132 In the PRC's view, overseas Chinese are an asset to demonstrating a positive image of China internationally.[47]: 133

Citizenship status

The Nationality Law of the People's Republic of China, which does not recognise dual citizenship, provides for automatic loss of PRC citizenship when a former PRC citizen both settles in another country and acquires foreign citizenship. For children born overseas of a PRC citizen, whether the child receives PRC citizenship at birth depends on whether the PRC parent has settled overseas: "Any person born abroad whose parents are both Chinese nationals or one of whose parents is a Chinese national shall have Chinese nationality. But a person whose parents are both Chinese nationals and have both settled abroad, or one of whose parents is a Chinese national and has settled abroad, and who has acquired foreign nationality at birth shall not have Chinese nationality" (Article 5).[97]

By contrast, the Nationality Law of the Republic of China, which both permits and recognises dual citizenship, considers such persons to be citizens of the ROC (if their parents have household registration in Taiwan).

Returning and re-emigration

With China's growing economic strength, many of the overseas Chinese have begun to migrate back to China, even though many mainland Chinese millionaires are considering emigrating out of the nation for better opportunities.[98]

In the case of Indonesia and Burma, political strife and ethnic tensions has caused a significant number of people of Chinese origins to re-emigrate back to China. In other Southeast Asian countries with large Chinese communities, such as Malaysia, the economic rise of People's Republic of China has made the PRC an attractive destination for many Malaysian Chinese to re-emigrate. As the Chinese economy opens up, Malaysian Chinese act as a bridge because many Malaysian Chinese are educated in the United States or Britain but can also understand the Chinese language and culture making it easier for potential entrepreneurial and business to be done between the people among the two countries.[99]

After the Deng Xiaoping reforms, the attitude of the PRC toward the overseas Chinese changed dramatically. Rather than being seen with suspicion, they were seen as people who could aid PRC development via their skills and capital. During the 1980s, the PRC actively attempted to court the support of overseas Chinese by among other things, returning properties that had been confiscated after the 1949 revolution. More recently PRC policy has attempted to maintain the support of recently emigrated Chinese, who consist largely of Chinese students seeking undergraduate and graduate education in the West. Many of the Chinese diaspora are now investing in People's Republic of China providing financial resources, social and cultural networks, contacts and opportunities.[100][101]

The Chinese government estimates that of the 1,200,000 Chinese people who have gone overseas to study in the thirty years since China's economic reforms beginning in 1978; three-quarters of those who left have not returned to China.[102]

Beijing is attracting overseas-trained academics back home, in an attempt to internationalise its universities. However, some professors educated to the PhD level in the West have reported feeling "marginalised" when they return to China due in large part to the country's “lack of international academic peer review and tenure track mechanisms”.[103]

Language

The usage of Chinese by the overseas Chinese has been determined by a large number of factors, including their ancestry, their migrant ancestors' "regime of origin", assimilation through generational changes, and official policies of their country of residence. The general trend is that more established Chinese populations in the Western world and in many regions of Asia have Cantonese as either the dominant variety or as a common community vernacular, while Standard Chinese is much more prevalent among new arrivals, making it increasingly common in many Chinatowns.[104][105]

Country statistics

There are over 50 million overseas Chinese.[106][107][108] Most of them are living in Southeast Asia where they make up a majority of the population of Singapore (75%) and significant minority populations in Malaysia (22.8%), Thailand (14%) and Brunei (10%).

See also

- Chinese folk religion & Chinese folk religion in Southeast Asia

- Chinatown, the article and Category:Chinatowns the international category list

- Chinese kin, Kongsi & Ancestral shrine

- Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association

- Chinese Americans

- Chinese Indonesians

- Chinese people in India

- Chinese people in Japan

- Chinese people in Kenya

- Chinese people in Korea

- Chinese people in Madagascar

- Chinese people in Myanmar

- Chinese people in New York City

- Chinese people in Nigeria

- Chinese people in Papua New Guinea

- Chinese people in Portugal

- Chinese people in Spain

- Chinese people in Sri Lanka

- Chinese people in Turkey

- Chin Haw

- List of overseas Chinese

- Migration in China

- Kapitan Cina

- List of politicians of Chinese descent

- Overseas Chinese banks

- Legislation on Chinese Indonesians

- Chinese Exclusion Act (Scott Act, 1888 & Geary Act, 1892) in United States

- Chinese Immigration Act, 1885 & Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 in Canada

- Chinese head tax & 1886 Vancouver anti-Chinese riots

- Lost Years: A People's Struggle for Justice

- Overseas Chinese Affairs Office

References

Further reading

- Barabantseva, Elena. Overseas Chinese, Ethnic Minorities and Nationalism: De-centering China, Oxon/New York: Routledge, 2011.

- Brauner, Susana, and Rayén Torres. "Identity Diversity among Chinese Immigrants and Their Descendants in Buenos Aires." in Migrants, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers in Latin America (Brill, 2020) pp. 291–308.

- Chin, Ung Ho. The Chinese of South East Asia (London: Minority Rights Group, 2000). ISBN 1-897693-28-1

- Chuah, Swee Hoon, et al. "Is there a spirit of overseas Chinese capitalism?." Small Business Economics 47.4 (2016): 1095-1118 online

- Fitzgerald, John. Big White Lie: Chinese Australians in White Australia, (UNSW Press, Sydney, 2007). ISBN 978-0-86840-870-5

- Gambe, Annabelle R. (2000). Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship and Capitalist Development in Southeast Asia (illustrated ed.). LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3825843861. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Kuhn, Philip A. Chinese Among Others: Emigration in Modern Times, (Rowman & Littlefield, 2008).

- Le, Anh Sy Huy. "The Studies of Chinese Diasporas in Colonial Southeast Asia: Theories, Concepts, and Histories." China and Asia 1.2 (2019): 225–263.

- López-Calvo, Ignacio. Imaging the Chinese in Cuban Literature and Culture, Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 2008. ISBN 0-8130-3240-7

- Ngai, Mae. The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics (2021), Mid 19c in California, Australia and South Africa excerpt

- Ngai, Pun; Chan, Jenny (2012). "Global capital, the state, and Chinese workers: The Foxconn experience". Modern China. 38 (4): 383–410. doi:10.1177/0097700412447164. S2CID 151168599.

- Pan, Lynn. The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas, (Harvard University press, 1998). ISBN 981-4155-90-X

- Reid, Anthony; Alilunas-Rodgers, Kristine, eds. (1996). Sojourners and Settlers: Histories of Southeast China and the Chinese. Contributor Kristine Alilunas-Rodgers (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824824464. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Sai, Siew-Min. "Mandarin lessons: modernity, colonialism and Chinese cultural nationalism in the Dutch East Indies, c. 1900s." Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 17.3 (2016): 375–394. online Archived 27 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Sai, Siew-Min. "Dressing Up Subjecthood: Straits Chinese, the Queue, and Contested Citizenship in Colonial Singapore." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 47.3 (2019): 446–473. online Archived 27 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Tan, Chee-Beng. Chinese Overseas: Comparative Cultural Issues, Hong Kong University Press, 2004.

- Taylor, Jeremy E. ""Not a Particularly Happy Expression":"Malayanization" and the China Threat in Britain's Late-Colonial Southeast Asian Territories." Journal of Asian Studies 78.4 (2019): 789-808. online

- Van Dongen, Els, and Hong Liu. "The Chinese in Southeast Asia." in Routledge Handbook of Asian Migrations (2018). online

External links

Media related to Chinese expatriates at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chinese expatriates at Wikimedia Commons