In geometry, the kissing number of a mathematical space is defined as the greatest number of non-overlapping unit spheres that can be arranged in that space such that they each touch a common unit sphere. For a given sphere packing (arrangement of spheres) in a given space, a kissing number can also be defined for each individual sphere as the number of spheres it touches. For a lattice packing the kissing number is the same for every sphere, but for an arbitrary sphere packing the kissing number may vary from one sphere to another.

Other names for kissing number that have been used are Newton number (after the originator of the problem), and contact number.

In general, the kissing number problem seeks the maximum possible kissing number for n-dimensional spheres in (n + 1)-dimensional Euclidean space. Ordinary spheres correspond to two-dimensional closed surfaces in three-dimensional space.

Finding the kissing number when centers of spheres are confined to a line (the one-dimensional case) or a plane (two-dimensional case) is trivial. Proving a solution to the three-dimensional case, despite being easy to conceptualise and model in the physical world, eluded mathematicians until the mid-20th century.[1][2] Solutions in higher dimensions are considerably more challenging, and only a handful of cases have been solved exactly. For others, investigations have determined upper and lower bounds, but not exact solutions.[3]

Known greatest kissing numbers

One dimension

In one dimension,[4] the kissing number is 2:

Two dimensions

In two dimensions, the kissing number is 6:

Proof: Consider a circle with center C that is touched by circles with centers C1, C2, .... Consider the rays C Ci. These rays all emanate from the same center C, so the sum of angles between adjacent rays is 360°.

Assume by contradiction that there are more than six touching circles. Then at least two adjacent rays, say C C1 and C C2, are separated by an angle of less than 60°. The segments C Ci have the same length – 2r – for all i. Therefore, the triangle C C1 C2 is isosceles, and its third side – C1 C2 – has a side length of less than 2r. Therefore, the circles 1 and 2 intersect – a contradiction.[5]

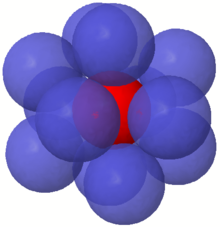

Three dimensions

In three dimensions, the kissing number is 12, but the correct value was much more difficult to establish than in dimensions one and two. It is easy to arrange 12 spheres so that each touches a central sphere, with a lot of space left over, and it is not obvious that there is no way to pack in a 13th sphere. (In fact, there is so much extra space that any two of the 12 outer spheres can exchange places through a continuous movement without any of the outer spheres losing contact with the center one.) This was the subject of a famous disagreement between mathematicians Isaac Newton and David Gregory. Newton correctly thought that the limit was 12; Gregory thought that a 13th could fit. Some incomplete proofs that Newton was correct were offered in the nineteenth century, most notably one by Reinhold Hoppe, but the first correct proof (according to Brass, Moser, and Pach) did not appear until 1953.[1][2][6]

The twelve neighbors of the central sphere correspond to the maximum bulk coordination number of an atom in a crystal lattice in which all atoms have the same size (as in a chemical element). A coordination number of 12 is found in a cubic close-packed or a hexagonal close-packed structure.

Larger dimensions

In four dimensions, it was known for some time that the answer was either 24 or 25. It is straightforward to produce a packing of 24 spheres around a central sphere (one can place the spheres at the vertices of a suitably scaled 24-cell centered at the origin). As in the three-dimensional case, there is a lot of space left over — even more, in fact, than for n = 3 — so the situation was even less clear. In 2003, Oleg Musin proved the kissing number for n = 4 to be 24.[7][8]

The kissing number in n dimensions is unknown for n > 4, except for n = 8 (where the kissing number is 240), and n = 24 (where it is 196,560).[9][10] The results in these dimensions stem from the existence of highly symmetrical lattices: the E8 lattice and the Leech lattice.

If arrangements are restricted to lattice arrangements, in which the centres of the spheres all lie on points in a lattice, then this restricted kissing number is known for n = 1 to 9 and n = 24 dimensions.[11] For 5, 6, and 7 dimensions the arrangement with the highest known kissing number found so far is the optimal lattice arrangement, but the existence of a non-lattice arrangement with a higher kissing number has not been excluded.

Some known bounds

The following table lists some known bounds on the kissing number in various dimensions.[12] The dimensions in which the kissing number is known are listed in boldface.

| Dimension | Lower bound | Upper bound |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| 2 | 6 | |

| 3 | 12 | |

| 4 | 24[7] | |

| 5 | 40 | 44 |

| 6 | 72 | 78 |

| 7 | 126 | 134 |

| 8 | 240 | |

| 9 | 306 | 363 |

| 10 | 510 | 553 |

| 11 | 592 | 868 |

| 12 | 840 | 1,355 |

| 13 | 1,154 | 2,064 |

| 14 | 1,932 | 3,174 |

| 15 | 2,564 | 4,853 |

| 16 | 4,320 | 7,320 |

| 17 | 5,346 | 10,978 |

| 18 | 7,398 | 16,406 |

| 19 | 10,668 | 24,417 |

| 20 | 17,400 | 36,195 |

| 21 | 27,720 | 53,524 |

| 22 | 49,896 | 80,810 |

| 23 | 93,150 | 122,351 |

| 24 | 196,560 | |

Generalization

The kissing number problem can be generalized to the problem of finding the maximum number of non-overlapping congruent copies of any convex body that touch a given copy of the body. There are different versions of the problem depending on whether the copies are only required to be congruent to the original body, translates of the original body, or translated by a lattice. For the regular tetrahedron, for example, it is known that both the lattice kissing number and the translative kissing number are equal to 18, whereas the congruent kissing number is at least 56.[13]

Algorithms

There are several approximation algorithms on intersection graphs where the approximation ratio depends on the kissing number.[14] For example, there is a polynomial-time 10-approximation algorithm to find a maximum non-intersecting subset of a set of rotated unit squares.

Mathematical statement

The kissing number problem can be stated as the existence of a solution to a set of inequalities. Let

Thus the problem for each dimension can be expressed in the existential theory of the reals. However, general methods of solving problems in this form take at least exponential time which is why this problem has only been solved up to four dimensions. By adding additional variables,

Therefore, to solve the case in D = 5 dimensions and N = 40 + 1 vectors would be equivalent to determining the existence of real solutions to a quartic polynomial in 1025 variables. For the D = 24 dimensions and N = 196560 + 1, the quartic would have 19,322,732,544 variables. An alternative statement in terms of distance geometry is given by the distances squared

This must be supplemented with the condition that the Cayley–Menger determinant is zero for any set of points which forms a (D + 1) simplex in D dimensions, since that volume must be zero. Setting

See also

Notes

References

- T. Aste and D. Weaire The Pursuit of Perfect Packing (Institute Of Physics Publishing London 2000) ISBN 0-7503-0648-3

- Table of the Highest Kissing Numbers Presently Known maintained by Gabriele Nebe and Neil Sloane (lower bounds)

- Bachoc, Christine; Vallentin, Frank (2008). "New upper bounds for kissing numbers from semidefinite programming". Journal of the American Mathematical Society. 21 (3): 909–924. arXiv:math.MG/0608426. Bibcode:2008JAMS...21..909B. doi:10.1090/S0894-0347-07-00589-9. MR 2393433. S2CID 204096.

External links

- Grime, James. "Kissing Numbers" (video). youtube. Brady Haran. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 11 October 2018.