The Garni Temple[b] is the only standing Greco-Roman colonnaded building in Armenia. Built in the Ionic order, it is located in the village of Garni, in central Armenia, around 30 km (19 mi) east of Yerevan. It is the best-known structure and symbol of pre-Christian Armenia. It has been described as the "easternmost building of the Graeco-Roman world"[7][c] and the only extant Greco-Roman temple in the former Soviet Union.[d]

| Garni Temple | |

|---|---|

The temple in 2021 | |

| General information | |

| Status | Museum (part of a larger protected area), occasional Hetanist (neopagan) shrine |

| Type | Pagan temple or tomb[1][2] |

| Architectural style | Ancient Greek/Roman |

| Location | Garni, Kotayk Province, Armenia |

| Coordinates | 40°06′45″N 44°43′49″E / 40.112421°N 44.730277°E |

| Completed | 1st or 2nd century AD[1] |

| Destroyed | 1679 |

| Management | Armenian Ministry of Culture |

| Height | 10.7 metres (35 ft)[a] |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Basalt[4] |

| Floor area | 15.7 by 11.5 m (52 by 38 ft)[3] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Alexander Sahinian (reconstruction, 1969–75) |

The structure was probably built by king Tiridates I in the first century AD as a temple to the sun god Mihr. After Armenia's conversion to Christianity in the early fourth century, it was converted into a royal summer house of Khosrovidukht, the sister of Tiridates III. According to some scholars it was not a temple but a tomb, and thus survived the destruction of pagan structures. It collapsed in a 1679 earthquake. Renewed interest in the 19th century led to excavations at the site in the early and mid-20th century, and its eventual reconstruction between 1969 and 1975, using the anastylosis method. It is one of the main tourist attractions in Armenia and the central shrine of Hetanism (Armenian neopaganism).

Setting

The site is in the village of Garni, in Armenia's Kotayk Province. The temple is at the edge of a triangular promontory rising above the ravine of the Azat River and the Gegham mountains.[9] It is a part of the fortress of Garni,[e] one of Armenia's oldest,[10] that was strategically significant for the defense of the major cities in the Ararat plain.[9] Besides the temple, the site contains a Bronze Age cyclopean masonry wall, a cuneiform inscription by king Argishti I of Urartu (who called it Giarniani),[11] a Roman bath with a partly preserved mosaic floor with a Greek inscription,[12] ruins of palace, other "paraphernalia of the Greco-Roman world",[13] the medieval round church of St. Sion, and other objects (e.g., medieval khachkars).[14] It is situated at 1,400 m (4,600 ft) above sea level.[15] In the first century, Tacitus mentioned castellum Gorneas as a major fortress in his Annals.[16][11]

Date and function

The precise date and the classification of the structure as a temple remain topics of continual scholarly debate.[17] Christina Maranci calls it an Ionic structure with an "unclear function." She writes that "while often identified as temple, it may have been a funerary monument, perhaps serving as a royal tomb."[18]

The generally accepted view, especially in Armenian historiography, postulates that it was built in 77 AD, during the reign of king Tiridates I of Armenia.[f] The date is calculated based on a Greek inscription, which names Tiridates the Sun (Helios Tiridates) as the founder of the temple.[g][9][26] Movses Khorenatsi incorrectly attributed the inscription to Tiridates III, but most scholars now attribute it to Tiridates I.[27] The inscription states that the temple was constructed in the eleventh year of the reign of Tiridates, leading scholars to believe it was completed in 77 AD.[27][19] This date is calculated based on Tiridates's visit to Rome in 66 AD, during which he was crowned by the Roman emperor Nero.[h] To rebuild the city of Artaxata, destroyed by the Roman general Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo, Nero gave Tiridates 50 million drachmas and provided him with Roman craftsmen. Upon his return to Armenia, Tiridates began a major project of reconstruction, which included rebuilding the fortress of Garni.[30] It is during this period that the temple is thought to have been built.[31]

| ||

| Greek text[32] | Translation by Russell[33] | Reading by Ananian[34] |

|---|---|---|

| Ἣλιος Τιριδάτης [ὁ μέγας] μεγάλης Ἀρμενίας ἄνα[κτος] ὡς δεσπότης. Αἴκτισε ναΐ[διον] βασιλίσ[σ]α τὸν ἀνίκητον κασ[ιν ἐνι] αιτούς. Αι. Τῆς βασιλεί[ας αὐτου] με[γαλείας]. Ὑπὸ ἐξουσίᾳ στεγάν[ου] λίτουργος τῷ μεγάλῳ σπ[ῆι εὔχεσθε] μετὰ ματήμι καὶ εὐχαρ[ιστίαν εὐχήν] τοῦ μαρτυρίου. | The Sun Tiridatēs of Greater Armenia, lord as despot, built a temple for the queen; the invincible... in the eleventh year of his reign. ...Under the protection of the... may the priest to the great cave (?) in the vain (?) of the witness and thanks. | The Sun God Tiridates, uncontested king of Great Armenia built the temple and the impregnable fortress in the eleventh year of his reign when Mennieay was hazarapet [chiliarch] and Amateay was sparapet [commander]. |

In Armenia, the temple is commonly believed to have been dedicated to Mihr, the sun god in the Zoroastrian-influenced Armenian mythology and the equivalent of Mithra.[i][38] Tiridates, like other Armenian monarchs, considered Mihr his patron. Some scholars argue that, given the historical context in which the temple was constructed—specifically, after his return from Rome as king—it would be logical to assume that Tiridates dedicated the temple to his patron god.[31] Furthermore, in 2011, white marble sculptures of bull hooves were discovered some 20 metres (66 ft) from the temple, potentially the remnants of a Mihr sculpture, who was often portrayed in a fight with a bull.[39][40]

Scholars believe that Greeks or Romans were involved in its construction. Telfer believed that it was built by Greek workmen and its Grecian style reflects Tiridates's desire to "introduce a taste for higher art among his people."[41][42] Arshak Fetvadjian suggested that it was built by "Roman architects for Tiridat and probably for the pagan cult of the Græco-Roman gods."[43] Maranci found stylistic similarities with structures in Asia Minor and suggested that imperial Roman workmen may have taken part in its construction.[18] Vrej Nersessian argued that while the "design and ornament are typically Roman, the workmen were local, with experience of carving basalt."[27] Varazdat Harutyunyan believed that local workmen were also involved.[3]

Some scholars argue that it may have been built on top of a Urartian temple.[36][44]

Mausoleum or tomb

Not all scholars are convinced that the structure was a temple. Among early sceptics, Kamilla Trever suggested in 1950 that based on a different interpretation of the extant literature and the evidence provided by coinage, the erection of the temple started in 115 AD. The pretext for its construction would have been the declaration of Armenia as a Roman province[27] and the temple would have housed the imperial effigy of Trajan.[45]

In 1982 Richard D. Wilkinson suggested that the building is a tomb, probably constructed c. 175 AD in honor of one of the Romanized kings of Armenia of the late 2nd century. This theory is based on a comparison to Graeco-Roman buildings of western Asia Minor (e.g. Nereid Monument, Belevi Mausoleum, Mausoleum at Halicarnassus),[16] the discovery of nearby graves that date to about that time, and the discovery of a few marble pieces of the Asiatic sarcophagus style. Wilkinson furthermore states that there is no direct evidence linking the structure to Mithras or Mihr, and that the Greek inscription attributed to Tiridates I probably refers to the fortress and not to the colonnaded structure. He also notes that it is unlikely that a pagan temple would survive destruction during Armenia's 4th-century conversion to Christianity when all other such temples were destroyed.[46][21]

James R. Russell finds the view of the structure being a temple of Mihr baseless and is skeptical that the Greek inscription refers to the temple.[47] He suggested that the "splendid mausoleum" was erected by Romans living in Armenia.[48] Russell agreed with Wilkinson's interpretation that it was a 2nd century tomb, "possibly of one of the Romanized kings of Armenia," such as Sohaemus, and that it is "unique for the country and testifies to a particularly strong Roman presence."[49] Felix Ter-Martirosov also believed it was built in the latter half of the 2nd century.[50] Robert H. Hewsen argued, based on the construction of a church in the 7th century next to it rather than in its place, that the building was "more likely the tomb of one of the Roman-appointed kings of Armenia," such as Tiridates I or Sohaemus (r. 140–160).[10]

Christian period and collapse

In the early fourth century,[j] when King Tiridates III adopted Christianity as Armenia's state religion, all pagan places of worship in the country were destroyed.[54] Scholars regard it as the only pagan, Hellenistic, or Greco-Roman structure to have survived the widespread destruction.[k][l] Scholars continue to debate why it was exempted from destruction. Zhores Khachatryan argues that it underwent depaganization and was thereafter seen as a fine structure within the royal palace complex.[61] Tananyan believes that it was recognized as an artistic masterpiece, which saved it from destruction.[62]

According to Movses Khorenatsi a "cooling-off house" (tun hovanots) was built within the fortress of Garni for Khosrovidukht, the sister of Tiridates III. Some scholars believe the temple was thus turned into a royal summer house.[9][58][63] The structure presumably underwent some changes. Cult statue(s) in the cella were removed, the opening in the roof for skylight was closed, and the entrance was transformed and adjusted for residence.[62] Ter-Martirosov argued that after Armenia's Christianization, it was initially a royal shrine, but after Khosrovidukht's death c. 325/326 it was transformed into a Christian mausoleum dedicated to her.[50] Hamlet Petrosyan and Zhores Khachatryan rejected the postulated Christianization of the temple.[30]

The walls of the temple bear six Arabic inscriptions in the Kufic style and one in Persian in the naskh script, which have all been paleographically dated to the 9th-10th centuries.[64][21] They commemorate the capture of the fortress and the temple's conversion into a mosque.[36] There is also a large Armenian inscription on its entryway. It was left by Princess Khoshak of Garni, the granddaughter of Ivane Zakarian (commander of Georgian-Armenian forces in the early 13th century) and Khoshak's son, Amir Zakare, in 1291. It records the release of the people of Garni from taxes in forms of wine, goats, and sheep.[65]

Simeon of Aparan, a poet and educator, made the last written record about the temple before its collapse in his 1593 poem titled "Lamentation on the Throne of Trdat" («Ողբանք ի վերայ թախթին Տրդատայ թագաւորին»).[66][67][m] The Garni fort was damaged when it was captured twice during the Ottoman–Persian Wars, in 1604 and 1638.[69]

The entire colonnade collapsed in a devastating earthquake on June 4, 1679,[70][71] with its epicenter situated in the Garni Gorge.[72][73] Most of the original building blocks remained scattered at the site. As much as 80% of the original masonry and ornamental friezes were at the site by the late 1960s.[74]

Renewed interest and reconstruction

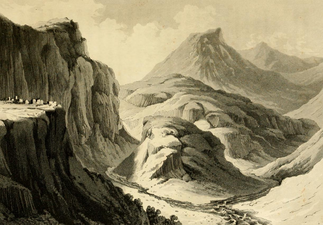

European travelers mentioned the temple in their works as early as the 17th century.[1] Jean Chardin (1673, who visited Armenia before the earthquake) and James Morier (1810s)[75] both incorrectly described it through local informants since they never actually visited the site.[16] Robert Ker Porter, who visited in the late 1810s, described what he saw as a "confused pile of beautiful fragments; columns, architraves, capitals, friezes, all mingled together in broken disorder." He provided a drawing of the site.[16][76] Another European to visit and document the ruins of the temple was Frédéric DuBois de Montperreux, who proposed a reconstruction plan in his 1839 book.[16] John Buchan Telfer, who visited in the 1870s, wrote that the ruins "lie tumbled in marvellous disorder."[42] He removed a fragment of the architrave bearing a lion head, which was displayed at the Royal Society of Arts in 1891, during his lecture on Armenia.[41] He subsequently bequeathed it to the British Museum, where it remains to this day.[77]

- Robert Ker Porter's 1821 drawing of the Garni Gorge.[78] The ruins are on the promontory on the left.[16]

- Toros Toramanian sitting on part of the pediment[81]

- The ruins in 1947[82]

In 1880 the Russian archaeologist Aleksey Uvarov, possibly inspired by the contemporaneous relocation of the Pergamon Altar from Asia Minor to Germany, proposed that the stones be moved to Tiflis (in Georgia) and be reconstructed there according to de Montpereux's plan.[83] Lori Khatchadourian suggests that the proposal "could be read as an attempt at co-opting Armenia's Roman past to the glory of Russia through the relocation of its most iconic monument to the nearest administrative center."[83] The governor of Erivan, citing technical difficulties with moving its parts, did not implement the plan and the project was aborted.[84][85]

In the subsequent decades scholars such as Nikoghayos Buniatian, Babken Arakelyan, and Nikolay Tokarsky studied the temple.[62] In 1909–11, during an excavation led by Nicholas Marr, the temple ruins were uncovered. Buniatian sought to reconstruct the temple in the 1930s.[84]

In 1949 the Armenian Academy of Sciences began major excavations of the Garni fortress site led by Babken Arakelyan. Architectural historian Alexander Sahinian focused on the temple itself. It was not until almost twenty years later, on December 10, 1968, that the Soviet Armenian government approved the reconstruction plan of the temple. A group led by Sahinian began reconstruction works in January 1969. It was completed by 1975,[86] almost 300 years after it was destroyed in an earthquake.[35][87] The temple was almost entirely rebuilt using its original stones, except the missing pieces which were filled with blank (undecorated) stones.[84]

The restoration has been well-received. Michael Greenhalgh wrote that the "almost perfect reconstruction" showed how little were removed, although he called it "decidedly an exception."[88] A U.S. historic preservation team noted:[89]

About a third of the reconstruction was of original materials and two-thirds of new materials. The new stone, of the same variety and color as the old, was obtained from a local quarry. Cutting of this stone was done onsite. The profiles of the original were reproduced without the embellishments of the original and without any attempt at fakery or antiquing. If a reconstruction must be done, this is an admirable approach.

The Soviet Armenian leader Karen Demirchyan pointed to its restoration as a "case in point" in the protection and restoration of historic monuments in the Soviet period.[6] For drawing up and supervising the project, Sahinian was awarded the State Prize of the Armenian SSR in 1975.[90] In 1978 a fountain-monument dedicated to Sahinian's reconstruction was erected near the temple.[87]

Architecture

Overview

It follows the general style of classical Ancient Greek architecture and has been described as Greek, Roman, Greco-Roman, or Hellenistic.[91] Natalie Kampen noted that it "shares a Graeco-Roman vocabulary with the use of basalt rather than marble."[17] Toros Toramanian stressed the singularity of the temple as a Roman-style building in the Armenian Highlands and noted that it "essentially had no influence on contemporary or subsequent Armenian architecture."[92] Sirarpie Der Nersessian argued that the temple, of a Roman type, "lies outside the line of development of Armenian architecture."[93] Fetvadjian described it as "of pure Roman style."[43]

Sahinian, the architect who oversaw its reconstruction, emphasized the local Armenian influence on its architecture, calling it an "Armenian-Hellenic" monument.[94] He further insisted that it resembles the ninth century BC Urartian Musasir temple.[95] Based on a comparative analysis, Sahinian also proposed that the design of the columns have their origins in Asia Minor.[96]

Maranci notes that its entablature is similar to that of the temple of Antoninus Pius at Sagalassos in western Asia Minor and to the columns of Attalia.[18]

In its small proportions,[43] the temple has been compared to the Roman temples of Maison carrée in Nîmes, and Temple of Augustus and Livia in Vienne, France.[97][98] William H. McNeill described it as a "small and undistinguished Roman-style temple."[99]

Exterior

The temple is constructed of locally quarried grey basalt,[4][16] assembled without the use of mortar.[5][18] Instead, the blocks are bound together by iron and bronze clamps.[18] It is a peripteros, composed of a collonaded portico (pronaos) and a cella (naos), erected on an elevated podium (base).[4][84] The podium, measuring 15.7 by 11.5 m (52 by 38 ft) and standing 2.8–3 m (9 ft 2 in – 9 ft 10 in) above ground,[3][36] is supported by a total of twenty-four Ionic order columns, each 6.54 m (21.5 ft) high: six in the front and back, and eight on the sides (with the corner columns counted twice).[4][91]

There is a 8–8.5 m (26–28 ft) wide stairway on the northern side leading to the chamber.[3][36] It consists of nine steep steps,[100] each measuring 30 cm (12 in) in height—approximately twice the average step height.[101] Tananyan proposes that ascending these steps compels individuals to feel humbled and exert physical effort to reach the altar.[102] On both sides of the stairway, there are roughly square pedestals. Sculpted on both of these pedestals is Atlas, the Greek mythological Titan who bore the weight of the earth, seemingly attempting to support the entire temple on its shoulders. Originally, it is assumed that these pedestals served the purpose of holding up altars, sacrificial tables.[102]

The exterior of the temple is richly decorated. The triangular pediment contains sculptures of plants and geometrical figures.[102] The frieze depicts a continuous line of acanthus. Furthermore, there are ornaments on the capital, architrave, and soffit. The stones in the front cornice have projecting sculptures of lion heads.[39] Sirarpie Der Nersessian argued that its "rich acanthus scrolls, with interposed lion masks and occasional palmettes, the fine Ionic and acanthus capitals, the other floral and geometric ornaments, are typical of the contemporary monuments of Asia Minor."[103]

- Ground plan

- Front view

- Fragment of frieze

Cella

The cella of the temple is 7.13 m (23.4 ft) high, 7.98 m (26.2 ft) long, and 5.05 m (16.6 ft) wide.[102] It covers an area of 40.3 m2 (434 sq ft). Due to the relatively small size of the cella, it has been proposed that a statue once stood inside and the ceremonies were held in the outside.[39] The cella is lit from two sources: the disproportionately large entrance of 2.29 by 4.68 metres (7 ft 6 in by 15 ft 4 in) and the opening in the roof of 1.74 by 1.26 metres (5.7 by 4.1 ft).[104]

Current state and use

It is the sole standing Greco-Roman colonnaded building in Armenia (and the entire former Soviet Union),[d] and is, consequently, the most important monument of ancient and pre-Christian Armenia.[3][60][108] Dickran Kouymjian described the "Greco-Roman temple" as the "most visible example [of classical tradition in Armenian art]."[109] In independent Armenia, it has been featured on a 1993 stamp, an uncirculated 1994 silver commemorative coin,[110] and the obverse of 5,000-dram banknote (in circulation from 1995 to 2005).[111]

Tourist attraction

It became a tourist destination even before its reconstruction in the 1970s.[112] Today, it is, along with the nearby medieval monastery of Geghard, one of Armenia's most visited sites.[113][114] Many visitors opt to explore the two sites, collectively known as Garni–Geghard, during a day trip from Yerevan.[115][116] In 2013 some 200,000 people visited the temple.[117] The number of visitors almost doubled by 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, when Garni received almost 390,000 visitors, including 250,000 Armenians and 137,400 foreigners.[118]

Notable visitors include several presidents,[n] opera singer Montserrat Caballé,[123] American TV personalities Khloé and Kim Kardashian,[124] and Conan O'Brien,[125] Russian pop star Philipp Kirkorov.[126] In October 2023, during her visit to Armenia, France's Culture Minister Rima Abdul Malak announced the twinning of Garni with the Maison carrée in Nîmes.[127]

Preservation

The temple and the fortress are part of the Garni Historical and Cultural Museum Reserve, which occupies 3.5 hectares (8.6 acres) and is supervised by the Service for the Protection of Historical Environment and Cultural Museum Reservations, an agency of the Armenian Ministry of Culture.[117] The government-approved list of historical and cultural monuments includes 11 objects within the site.[14]

In a 2006 survey the state of conservation of Garni was rated by over three-quarters of the visitors as "good" or "very good".[116] In 2011 UNESCO awarded the Museum-Reservation of Garni the Melina Mercouri International Prize for the Safeguarding and Management of Cultural Landscapes for "measures taken to preserve its cultural vestiges, and the emphasis placed on efforts to interpret and open the site for national and international visitors."[128]

Incidents

On September 25, 2014 a Russian tourist in his early 20s, defaced the temple by spray painting "В мире идол ничто" (literally translating to "In the world, idol is nothing").[129][130] The painting was cleaned days later.[131] The Armenian state service for protection of historical and cultural reserves filed a civil lawsuit against him in February 2015, in which the agency requested 839,390 AMD (~$1,760) to recover the damage resulting from vandalism.[132] In an April 2015 decision the Kotayk Province court ruled to fine him the requested amount.[133]

On September 4, 2021 a sanctioned private wedding ceremony took place at the site causing much controversy.[134] The site was closed for visitors that day.[135] The local authorities of Garni said they had opposed it in a written statement to the Culture Ministry.[136] The Culture Ministry said the agency responsible for the preservation of the site had acted independently in allowing the event to take place.[137]

Neopagan shrine

Since 1990,[138] the temple has been the central shrine[139][140] of the small number of followers of Armenian neopaganism (close to Zoroastrianism) who hold annual ceremonies at the temple,[141] especially on March 21—the pagan New Year.[138][142] On that day, which coincides with Nowruz, the Iranian New Year, Armenian neopagans celebrate the birthday of the god of fire, Vahagn.[143] Celebrations by neopagans are also held during the summer festival of Vardavar, which has pre-Christian (pagan) origins.[144][145]

Notable events

The torch of the first Pan-Armenian Games was lit near the temple on August 28, 1999.[146]

The square in front of the temple has been occasionally used as a venue for concerts:

- A concert of classical music was held near the temple on July 2, 2004 by the National Chamber Orchestra of Armenia, conducted by Aram Gharabekian.[147] The orchestra played the works of Aram Khachaturian, Komitas, Edvard Mirzoyan, Strauss, Mozart, and other composers.[148]

- On May 6, 2019 Acid Pauli performed a live concert of electronic music in front of the temple.[149][150][151]

- On July 14, 2019 Armenia's National Chamber Orchestra performed a concert in front of the temple dedicated to the 150th anniversaries of Komitas and Hovhannes Tumanyan.[152]

- On September 8, 2022 a Starmus VI festival event took place at the temple featuring the rock band Nosound, Sebu Simonian from the band Capital Cities, and the festival's speakers, including Charlie Duke, Charles Bolden, Kip Thorne, Brian Greene, Michel Mayor, George Smoot, John C. Mather as special guests.[153]

Gallery

- view from the steps of the temple

- Temple and ruins of buildings in 2018

- Temple in 2013

- Mosaic in bathhouse

- Part of forest wall

In film and television

- The ruins of the temple are depicted in the 1962 Soviet Armenian film Rings of Glory («Кольца славы»), featuring the Olympic gymnast Albert Azaryan.[154] and feature prominently in the second segment of the 1966 Soviet Armenian anthology film People of the Same City («Նույն քաղաքի մարդիկ») titled "Garni".[155][156]

- In 1985 an episode of the Soviet televised music festival Pesnya goda ("Song of the Year") was recorded near the temple.[157] It was noted for Alla Pugacheva's performance.[158]

- Some scenes of the 1985 Polish film Travels of Mr. Kleks (Podróże Pana Kleksa) were shot at the temple.[159][160]

- Several scenes of the 1986 Soviet musical film A Merry Chronicle of a Dangerous Voyage (Весёлая хроника опасного путешествия) were shot at the temple.[161]

- In the 2002 film Herostratus, a U.S.-Armenia co-production, director Ruben Kochar made "great, atmospheric use of unique locations unfamiliar to Western audiences," including Garni.[162]

- Garni features prominently in the 2007 Vigen Chaldranyan film The Priestess (Քրմուհին), where the priestess of the temple (portrayed by Ruzan Vit Mesropyan) commits adultery and is consequently expelled from it.[163][164]

- American comedian Conan O'Brien and his Armenian-American assistant Sona Movsesian filmed part of an episode dancing at the temple of Garni during their visit in October 2015.[165] The episode aired on his late-night talk show on November 17, 2015 and scored 1.3 million viewers.[166][167]

- In episode 6 ("Let the Good Times Roll") of the American reality television show The Amazing Race 28, first aired on April 1, 2016,[168] the contestants make a pit stop at the temple.[169]

- The 2022 Indian action film Rashtra Kavach Om, partially filmed in Armenia, features the Garni temple and other landmarks in the country.[170]

See also

References

- Notes

- References

Bibliography

- Books

- Canepa, Matthew P. (2018). The Iranian Expanse: Transforming Royal Identity through Architecture, Landscape, and the Built Environment, 550 BCE–642 CE. Oakland: University of California Press. pp. 115-118. ISBN 9780520290037.

- Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231139267.

- Nersessian, Vrej (2001). Treasures from the Ark: 1700 Years of Armenian Christian Art. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 9780892366392.

- Bauer-Manndorff, Elisabeth (1981). Armenia: Past and Present. Lucerne: Reich Verlag.

- Russell, James R. (1987). Zoroastrianism in Armenia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-96850-9.

- Strzygowski, Josef (1918). Die Baukunst der Armenier und Europa [The Architecture of the Armenians and of Europe] Volume 1 (in German). Vienna: Kunstverlag Anton Schroll & Co.

- Porter, Robert Ker (1821). Travels in Georgia, Persia, Armenia, ancient Babylonia, &c. &c. Volume II. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

- Kiesling, Brady (2000). Rediscovering Armenia: An Archaeological/Touristic Gazetteer and Map Set for the Historical Monuments of Armenia (PDF). Yerevan/Washington DC: Embassy of the United States of America to Armenia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-03.

- Lang, David Marshall (1970). Armenia: Cradle of Civilization. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Sahinian, Alexander (1983). Գառնիի անտիկ կառույցների ճարտարապետությունը [Architecture of antique constructions of Garni] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences Publishing.

- Harutyunyan, Varazdat (1992). Հայկական ճարտարապետության պատմություն [History of Armenian Architecture] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Luys. ISBN 5-545-00215-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2022. Alt URL

- Trever, Kamilla (1953). Orbeli, I. A. (ed.). Очерки по истории культуры древней Армении (II в. до н. э. — IV в. н. э.) [Essays on the history of the culture of ancient Armenia (II century BC - IV century AD)] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow: Soviet Academy of Sciences Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2021.

- Der Nersessian, Sirarpie (1969). The Armenians. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Khachatryan, Zhores (2001). "Գառնիի տաճարը հերեո՞ն, վկայարա՞ն". Հայոց սրբերը և սրբավայրերը [Armenian Saints and Sanctuaries] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Hayastan. pp. 244–254. ISBN 5-540-01771-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-08-07.

- Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-33228-4.

- Journal articles

- Abrahamian, A. G. (1947). Գառնիի հունարեն արձանագրությունը [The Greek inscription of Garni]. Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 4 (3–4): 61–72. Archived from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2018-09-26.

- Khatchadourian, Lori (2008). "Making Nations from the Ground up: Traditions of Classical Archaeology in the South Caucasus". American Journal of Archaeology. 112 (2): 247–278. doi:10.3764/aja.112.2.247. JSTOR 20627449. S2CID 163627047.

- Manandian, Hakob (1946). Գառնիի հունարեն արձանագրությունը և Գառնիի հեթանոսական տաճարի կառուցման ժամանակը [The Greek inscription of Garni and the construction date of the pagan temple of Garni] (in Armenian). Yerevan: State University Press. (PDF)

- Tananyan, Grigor (2014). Գառնի պատմամշակութային կոթողը (տաճարի վերականգման 40-ամյակի առթիվ) [The Historic & Cultural Monument of Garni (to the 40th anniversary of the restoration of the temple)]. Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). № 2 (2): 25–45. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Wilkinson, R. D. (1982). "A Fresh Look at the Ionic Building at Garni". Revue des Études Arméniennes (XVI): 221–244.

Further reading

- Manandyan, Hakob (1951). "Новые заметки о греческой надписи и языческом храме Гарни". Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences of the Armenian SSR: Social Sciences (in Russian). № 4 (4): 9–36. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Bartikian, Hrach (1965). "Գառնիի հունարեն անձանագրությունը և Մովսես Խորենացին [The Greek Inscription of Garni and Movses Khorenatsi]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). № 3 (3): 229–234. Archived from the original on 2016-11-11. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Mouradian, G. S. (1981). "Греческая надпись Трдата I, найденная в Гарни [Tiridates I's Greek Inscription Discovered in Garni]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Russian). № 3 (3): 81–94. Archived from the original on 2016-11-11. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Sahinian, Alexander (1979). "Գառնիի անտիկ տաճարի կառուցման ժամանակը [The Time of the Construction of the Antique Temple of Garny]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). № 3 (3): 165–181.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Sahinian, Alexander (1979). "Գառնիի անտիկ տաճարի վերակազմության գիտական հիմունքները [Scientific Foundations of the Reconstruction of the Ancient Temple of Garny]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). № 4 (4): 135–155. Archived from the original on 2016-11-10. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Sahinian, Alexander (1979). "Գառնիի անտիկ տաճարի վերականգնումը [The Reconstruction of the Ancient Temple of Garni]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian). № 10 (10): 59–74. ISSN 0320-8117. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Sahinian, Alexander (1979). "Գառնիի անտիկ տաճարի համաչափական համակարգը [Proportional System of the Ancient Temple of Garni]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian). № 12 (12): 76–92. ISSN 0320-8117.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Sargsian, Harma (1982). "Գառնիի հեթանոսական տաճարի վերականգնման ճարտարագիտական հարցերը [Engineering questions of the restoration of paganish temple of Garni]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian). № 12 (12): 70–76. ISSN 0320-8117.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Sahinian, Alexander (1983). Գառնիի անտիկ կառույցների ճարտարապետությունը [Architecture of ancient structures of Garni] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences Publishing.

- Sahinian, Alexander (1988). Архитектура античных сооружений Гарни [Architecture of ancient structures of Garni] (in Russian). Yerevan: Sovetakan Grogh.

External links

- Virtual tour of the Garni Temple

- "Arménie : Le temple de Garni au son du duduk". Le Monde (in French). 14 June 2011.

- Garni at Armenica.org