The 2015 United Kingdom general election was held on Thursday 7 May 2015 to elect 650 Members of Parliament (or MPs) to the House of Commons. It was the only general election held under the rules of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 and was the last general election to be held before the United Kingdom would vote to end its membership of the European Union (EU). Local elections took place in most areas of England on the same day.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

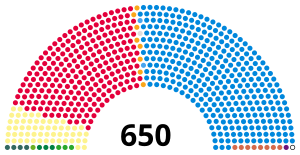

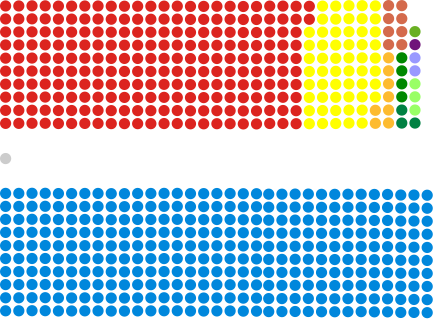

All 650 seats in the House of Commons 326 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Registered | 46,354,197 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 66.4%[1] ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

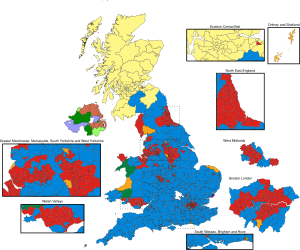

Colours denote the winning party, as shown in the main table of results. * Figure does not include the Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow, who was included in the Conservative seat total by some media outlets. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Composition of the House of Commons after the election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

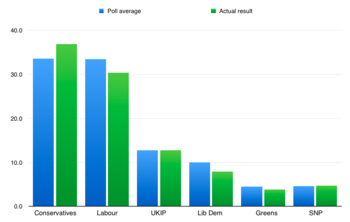

Opinion polls and political commentators had predicted that the results of the election would cause a second consecutive hung parliament whose composition would be similar to the previous Parliament, which was in effect from the previous national election in 2010. Opinion polls turned out to have underestimated the Conservatives, however, as they won 330 of the 650 seats and 36.9% of the votes, giving them a majority of ten seats (not including the Speaker, who cannot vote or debate and must remain impartial). This won them the right to govern the country alone and the right for their leader, David Cameron, to continue as Prime Minister.

The Labour Party, led by Ed Miliband, saw a small increase in its share of the vote to 30.4% but won 26 fewer seats than in 2010. This gave them 232 MPs. This was the fewest seats the party won since the 1987 general election, when it had 229 MPs returned. Many senior Labour MPs, such as Ed Balls, Douglas Alexander and Jim Murphy, lost their seats.

The Scottish National Party won a landslide victory in Scotland, mainly at the expense of Labour, who had held a majority of Scottish seats in the House of Commons at every general election since 1964. The SNP won 56 of the 59 Scottish seats and became the third-largest party in the House of Commons.

The Liberal Democrats, led by outgoing Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, had their worst result since their formation in 1988, losing 49 of their 57 seats, with Cabinet ministers Vince Cable, Ed Davey and Danny Alexander all losing their seats. The UK Independence Party came third in terms of votes with 12.6% but won only a single seat, with party leader Nigel Farage failing to win his seat of South Thanet. The Green Party won its highest ever vote share of 3.8% and retained their only seat.[2] In Northern Ireland, the Ulster Unionist Party returned to the Commons with two seats after their five-year long absence, and the Alliance Party lost its only seat despite an increase in their vote share. Following the election, Ed Miliband resigned as leader of the Labour Party and Nick Clegg resigned as leader of the Liberal Democrats.

The election is considered to have begun a political realignment in the UK, marking the end of the traditional three-party domination of the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats seen throughout the 20th century. The Scottish National Party began its domination of Scottish politics. It also saw the last public appearance of Charles Kennedy, the former Leader of the Liberal Democrats, before his death on 1 June 2015.

Notable MPs who retired at this election included former Prime Minister Gordon Brown, former Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling, former Leader of the Conservative Party William Hague and former Leader of the Liberal Democrats Menzies Campbell. Notable newcomers to the House of Commons include: future Leader of the SNP in the House of Commons Ian Blackford, future Deputy Leader of the Labour Party Angela Rayner, future Leader of the Labour Party Keir Starmer and future UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak. Another future UK Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, who had previously left Parliament in 2008 so he could serve as the Mayor of London, returned to Parliament as the MP for Uxbridge and South Ruislip.

Election process

The Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 led to the dissolution of the 55th Parliament on 30 March 2015 and the scheduling of the election on 7 May.[3] There were local elections on the same day in all of England, with the exception of Greater London. No elections were scheduled to take place in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland.

All British, Irish and Commonwealth citizens over the age of 18 residing in the UK that were not in prison, a mental hospital or on the run from law enforcement on the date of the election were permitted to vote. In British general elections, voting takes place in all constituencies in the United Kingdom to elect members of parliament (or MPs) to the House of Commons, the lower house of Parliament in the UK. Each constituency elects one MP to the House of Commons using the first-past-the-post voting system. If one party obtains a majority (326) of the 650 seats, then that party is entitled to form the Government. If no party has a majority, then there is what is known as a hung parliament. In this case, the options for forming the Government are either a minority government (where one party governs alone despite not having the majority of the seats) or a coalition government (where one party governs alongside party in order to get a majority of seats).[4]

Although the Conservative Party planned for the number of constituencies to be reduced from 650 to 600, through the Sixth Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies under the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011, the review of constituencies and reduction in seats was delayed by the Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013.[5][6][7][8] The next boundary review was set to take place in 2018; and so the 2015 general election was contested using the same constituencies and boundaries as in 2010. Of the 650 constituencies, 533 were in England, 59 were in Scotland, 40 were in Wales and 18 were in Northern Ireland.

In addition, the 2011 Act mandated a referendum in 2011 on changing from the first-past-the-post voting system to an alternative vote system for general elections. The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government agreed to holding a referendum.[9] The referendum was held in May 2011 and resulted in the retention of the existing voting system. Before the previous general election the Liberal Democrats had pledged to change the voting system, and the Labour Party had pledged to hold a referendum on any such change.[10] The Conservatives, however, promised to keep the first-past-the-post system, but to reduce the number of constituencies to 600. Liberal Democrats' plan was to reduce the number of MPs to 500, and for them to be elected using a proportional vote system.[11][12]

The Government increased the amount of money that parties and candidates were allowed to spend on campaigning during the election by 23%; a move decided against the advice of the Electoral Commission.[13] The election saw the first cap on spending by parties in individual constituencies during the 100 days before Parliament's dissolution on 30 March: £30,700, plus a per-voter allowance of 9p in county constituencies and 6p in borough seats. An additional voter allowance of more than £8,700 is available after the dissolution of Parliament. In total, parties spent £31.1m in the 2010 general election, of which the Conservative Party spent 53%, the Labour Party spent 25% and the Liberal Democrats 15%.[14] This was also the first UK general election to use individual rather than household voter registration.

Date of the election

An election is called following the dissolution of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The 2015 general election was the first to be held under the provisions of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011. Prior to this, the power to dissolve Parliament was a royal prerogative, exercised by the sovereign on the advice of the prime minister. Under the provisions of the Septennial Act 1715, as amended by the Parliament Act 1911, an election had to be announced on or before the fifth anniversary of the beginning of the previous parliament, barring exceptional circumstances. No sovereign had refused a request for dissolution since the beginning of the 20th century, and the practice had evolved that a prime minister would typically call a general election to be held at a tactically convenient time within the final two years of a Parliament's lifespan, to maximise the chance of an electoral victory for his or her party.[15]

Prior to the 2010 general election, the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats pledged to introduce fixed-term elections.[10] As part of the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreement, the Cameron ministry agreed to support legislation for fixed-term Parliaments, with the date of the next general election being 7 May 2015.[16] This resulted in the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, which removed the prime minister's power to advise the monarch to call an early election. The Act only permits an early dissolution if Parliament votes for one by a two-thirds supermajority, or if a majority of MPs pass a vote of no confidence and no new government is subsequently formed within 14 days.[17] However, the prime minister had the power, by order made by Statutory Instrument under section 1(5) of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, to fix the polling day to be up to two months later than 7 May 2015. Such a Statutory Instrument must be approved by each House of Parliament. Under section 14 of the Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013, the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 was amended to extend the period between the dissolution of Parliament and the following general election polling day from 17 to 25 working days. This had the effect of moving forward the date of the dissolution of the Parliament to 30 March 2015.[3]

Timetable

The key dates were:

| Monday 30 March | Dissolution of Parliament and the start of campaigning. |

| Saturday 2 May | Deadline to file nomination papers, to register to vote, and to request a postal vote.[18] |

| Thursday 7 May | Date of the election. |

| Friday 8 May | The Conservative Party wins the election with a majority of 10 seats. |

| Monday 18 May | New Parliament meets for the first time to elect a Speaker. |

| Wednesday 27 May | 2015 State Opening of Parliament. |

MPs not standing for re-election

While at the previous election there had been a record 149 MPs not standing for re-election,[19] the 2015 election saw 89 MPs standing down.[20] Out of these MPs, 37 were Conservatives, 37 were Labour, 10 were Liberal Democrats, 3 were Independents, 1 was Sinn Féin and 1 was Plaid Cymru. The highest-profile members of parliament leaving were: Gordon Brown, the former Prime Minister, and William Hague, the former Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition.[21] Alongside Brown and Hague, 17 former cabinet ministers stood down at the election, including Stephen Dorrell, Jack Straw, Alistair Darling, David Blunkett, Sir Malcolm Rifkind and Dame Tessa Jowell.[21] The highest profile Liberal Democrat to stand down was their former leader Sir Menzies Campbell, while the longest-serving MP, Sir Peter Tapsell, also retired, having served as an MP continuously since 1966, or for 49 years.[21]

Contesting political parties and candidates

Overview

On 9 April 2015, the deadline for standing for the general election, there were 464 political parties registered with the Electoral Commission. Candidates who did not belong to a party were either labelled as an Independent or not labelled at all.

The Conservative Party and the Labour Party had been the two biggest parties since 1922, and had supplied all the UK's prime ministers since 1935. Opininion polls had predicted that the two parties would receive a combined total of anywhere between 65% and 75% of votes, and would receive anywhere between 80% and 85% of the seats;[22][23] and that, as such, the leader of one of the two parties would become the Prime Minister after the election. The Liberal Democrats had been the third largest party in the UK for many years; but as described by various political commentators, other parties had risen relative to the Liberal Democrats since the 2010 election.[24][25] In order to emphasise this, The Economist stated that "the familiar three-party system of the Tories, Labour, and the Lib Dems appears to be breaking down with the rise of UKIP, the Greens and the SNP." Ofcom ruled that the major parties in Great Britain were the Conservatives, Labour, the Liberal Democrats and UKIP, the SNP a major party in Scotland, and Plaid Cymru a major party in Wales.[26] The BBC's guidelines were similar but removed UKIP from their list of major parties, and instead stated that UKIP should be given "appropriate levels of coverage in output to which the largest parties contribute and, on some occasions, similar levels of coverage".[27][28] Seven parties (Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrat, UKIP, SNP, PC and Green) participated in the election leadership debates.[29] Northern Ireland's political parties were not included in any debates, despite the DUP, a party based in Northern Ireland, being the fourth largest party in the UK going into the election.

National

Several parties operate in specific regions only. The main national parties, standing in most seats across all of the country, are listed below in order of the number of seats that they contested:

- Conservative Party: The Conservative Party was the senior party in the 2010-15 coalition government, having won the most seats (306) at the 2010 election. The party stood in 647 seats (every seat except for two in Northern Ireland and the Speaker's seat).

- Labour Party: Labour had been in power from 1997 to 2010. The party was Her Majesty's Most Loyal Opposition after the 2010 election, having won 258 seats. It stood in 631 constituencies,[n 2] missing only the Speaker's seat, and all seats in Northern Ireland.

- Liberal Democrats: The Liberal Democrats were the junior member of the 2010–15 coalition government, having won 57 seats. They contested 631 seats, and like Labour, only not contesting the Speaker's seat and all seats in Northern Ireland.

- UK Independence Party (or UKIP): UKIP won the fourth-most votes at the 2010 election, but failed to win any seats. They went into the election with two seats; due to winning two by-elections. They also won the most votes of any British party at the 2014 European election. It contested 624 seats across the United Kingdom.[n 3]

- Green Party: The Green Party went into the election with only one seat. However, they won the fourth-most votes in the 2014 European election. In 2010, Caroline Lucas became the party's first ever MP. In this election they received 3.8% of the vote. This made them the sixth largest party in terms of how many people voted for them. They stood in 573 seats.

Minor parties

Dozens of minor parties stood in this election. The Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition stood 135 candidates and was the only minor party to have more than forty candidates.[30] The Respect Party, who came into the election with one MP who was elected at the 2012 Bradford West by-election, stood four candidates. The British National Party, who finished fifth with 1.9% of the vote and stood 338 candidates at the 2010 general election, stood only eight candidates this year following a collapse in their support.[31] 753 other candidates stood at the general election, including Independents and candidates from other parties.[31]

Northern Ireland

The main parties in Northern Ireland in order of their number of seats were:

- Democratic Unionist Party (DUP): the DUP won eight seats in 2010, making it the largest party in Northern Ireland and the fourth biggest in the UK. The party also won the 2011 Northern Ireland Assembly election, and came in second out of the Northern Irish parties at the 2014 European election. It contested 16 of the 18 Northern Irish constituencies, having entered into an electoral pact to abstain from the two other seats with the Ulster Unionist Party.

- Sinn Féin: Sinn Féin won the most votes in Northern Ireland in 2010, but came second in the number of seats, winning five. They came second at the 2011 Northern Ireland Assembly election and they came in first out of the Northern Irish parties in the 2014 European election. In the House of Commons Sinn Féin are abstentionists, and so they have never taken up the seats that they have won there. The party also operates in Ireland, where it does take seats in parliament. It stood in all 18 Northern Irish constituencies.

- Social Democratic and Labour Party (or the SDLP): The SDLP third in terms of both votes and seats in the 2010 general election and 2011 Northern Ireland Assembly election, and fourth in the 2014 European election. Going into this election, the party had three MPs. The SDLP has a relationship with the Labour Party, with the SDLP's MPs generally following the Labour whip. In the case of a hung parliament, the party would have entered into a confidence-and-supply-agreement with the party.[32] They contested all 18 Northern Irish constituencies at the election.

- Ulster Unionist Party (or the UUP): in 2010 the UUP entered into an electoral alliance with the Conservative Party, and finished fourth in terms of votes in Northern Ireland, but won no seats. The party has one MEP, having placed third in the 2014 European elections. They came fourth in the 2011 Northern Ireland Assembly election. The UUP contested 15 of the 18 Northern Irish seats; the party did not run in two seats because of its electoral pact with the DUP, and also did not nominate a candidate against former party member, Sylvia Hermon.[33]

- Alliance Party of Northern Ireland: The Alliance Party had one MP going into this election, Naomi Long, who had been elected for the first time in 2010. They came fifth in the 2010 election by vote share. They have a relationship with the Liberal Democrats. However, the Alliance's one MP elected in 2010 sat on the opposition benches in the Commons and not with the Liberal Democrats on the government benches. The party contested all 18 Northern Irish constituencies in 2015.

Smaller parties in Northern Ireland included the Traditional Unionist Voice, who won no seats at this election but had one member of the Northern Ireland Assembly, the Conservatives and UKIP (both are major parties in the rest of the UK, but are minor parties here).[34]

Scotland

- Scottish National Party (or the SNP): The SNP only contested seats in Scotland and stood in all 59 Scottish constituencies. The party received the second-most votes in Scotland and the sixth-most overall in 2010, winning six seats. It won the 2011 election to the Scottish Parliament and had a surge of support since the Scottish independence referendum in September 2014, in which it was the main political party behind the losing Yes campaign.[35] Most projections suggested that it would be the third-largest party overall after the 2015 election, in terms of seats won, overtaking the Liberal Democrats.[23]

Smaller parties in Scotland include the Scottish Libertarian Party, but none of the smaller parties make much of an impact in general elections in Scotland.

Wales

- Plaid Cymru: led by Leanne Wood, who was a member of the Welsh Assembly and did not stand in the general election. Plaid Cymru organises only in Wales, where it contested all forty Welsh constituencies. The party has three MPs and was fourth in Wales (eighth overall) by vote share in 2010, later finishing third in the 2011 Welsh Assembly elections.

Wales has a number of smaller parties which, again, do not tend to make much impact in the general elections. In 2015, the Labour Party continued to dominate Welsh politics at the general elections.

Pacts and possible coalitions

Coalitions have been rare in the United Kingdom, because the first-past-the-post system has usually led to one party winning an overall majority in the Commons. However, with the outgoing Government being a coalition and with opinion polls not showing a large or consistent lead for any one party, there was much discussion about possible post-election coalitions or other arrangements, such as confidence and supply agreements.[36]

Some UK political parties that only stand in part of the country have reciprocal relationships with parties standing in other parts of the country. These include:

- Labour (in Great Britain) and SDLP (in Northern Ireland)

- Liberal Democrats (in Great Britain) and Alliance (in Northern Ireland)

- SNP (in Scotland) and Plaid Cymru (in Wales)

- Plaid Cymru also recommended supporters in England to vote Green,[37] while the SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon said she would vote for Plaid Cymru were she in Wales, and Green were she in England.[38] However, Sturgeon also said that, if their candidate was the most progressive, she would vote for Labour were she in England.[39]

- Green Party of England and Wales (in England and Wales), Scottish Greens (in Scotland) and the Green Party in Northern Ireland (in Northern Ireland)

On 17 March 2015 the Democratic Unionist Party and the Ulster Unionist Party agreed an election pact, whereby the DUP would not stand candidates in Fermanagh and South Tyrone (where Michelle Gildernew, the Sinn Féin candidate, won by only four votes in 2010) and in Newry and Armagh. In return the UUP would stand aside in Belfast East and Belfast North. The SDLP rejected a similar pact suggested by Sinn Féin to try to ensure that an agreed nationalist would win that constituency.[40][41][42] The DUP also called on voters in Scotland to support whichever pro-Union candidate was best placed to beat the SNP.[43]

Candidates

The deadline for parties and individuals to file candidate nomination papers to the acting returning officer (and the deadline for candidates to withdraw) was 4 p.m. on 9 April 2015.[44][45][46][47] The total number of candidates was 3,971; the second-highest number in history, slightly down from the record 4,150 candidates at the last election in 2010.[31][48]

There were a record number of female candidates standing in terms of both absolute numbers and percentage of candidates: 1,020 (26.1%) in 2015, up from 854 (21.1%) in 2010.[31][48] The proportion of female candidates for major parties ranged from 41% of Alliance Party candidates to 12% of UKIP candidates.[49] According to UCL's Parliamentary Candidates UK project[50] the major parties had the following percentages of black and ethnic minority candidates: the Conservatives 11%, the Liberal Democrats 10%, Labour 9%, UKIP 6%, the Greens 4%.[51] The average age of the candidates for the seven major parties was 45.[50]

The youngest candidates were all aged 18: Solomon Curtis (Labour, Wealden); Niamh McCarthy (Independent, Liverpool Wavertree); Michael Burrows (UKIP, Inverclyde); Declan Lloyd (Labour, South East Cornwall); and Laura-Jane Rossington (Communist Party, Plymouth Sutton and Devonport).[52][53][54] The oldest candidate was Doris Osen, 84, of the Elderly Persons' Independent Party (EPIC), who was standing in Ilford North.[53] Other candidates aged over 80 included three long-serving Labour MPs standing for re-election: Sir Gerald Kaufman (aged 84; Manchester Gorton), Dennis Skinner (aged 83; Bolsover) and David Winnick (aged 81; Walsall North).

A number of candidates—including two for Labour[55][56] and two for UKIP[57][58] – were suspended from their respective parties after nominations were closed. Independent candidate Ronnie Carroll died after nominations were closed.[59]

Campaign

By party

Conservative

In late 2014, the year before the election, the Conservatives decided to target Lib Dem seats as well as defending their own seats and targeting Conservative-Labour marginals, which ultimately contributed towards their victory.[60] In 2015 David Cameron launched the Conservative formal campaign in Chippenham on 30 March.[61] Throughout the campaign the Conservatives played on fears of a Labour-SNP coalition following the Scottish independence referendum the year before.[62]

Labour

The Labour campaign was launched on 27 March at Olympic Park in London.[63][64] Ed Miliband's EdStone was a major feature of the campaign which was covered by the media.[65] Deputy Leader of the Labour Party Harriet Harman embarked on a pink bus tour as part of her Woman to Woman campaign.[66]

Issues

Constitutional affairs

The Conservative manifesto committed to "a straight in-out referendum on our membership of the European Union by the end of 2017".[67] Labour did not support this, but did commit to an EU membership referendum if any further powers were transferred to the European Union.[68] The Lib Dems also supported the Labour position, but explicitly supported the UK's continuing membership of the EU.

The election was the first following the 2014 Scottish independence referendum. None of the three major party manifestos supported a second referendum and the Conservative manifesto stated that "the question of Scotland's place in the United Kingdom is now settled". In the run-up to the election, David Cameron coined the phrase "Carlisle principle" for the idea that checks and balances are required to ensure that devolution to Scotland has no adverse effects on other parts of the United Kingdom.[69][70] The phrase references a fear that Carlisle, being the English town closest to the Scottish border, could be affected economically by preferential tax rates in Scotland.

Government finance

The deficit, who was responsible for it and plans to deal with it were a major theme of the campaign. While some smaller parties opposed austerity,[71] the Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats, UKIP and the Greens all supported some further cuts, albeit to different extents.

Conservative campaigning sought to blame the deficit on the previous Labour government. Labour, in return, sought to establish their fiscal responsibility. With the Conservatives also making several spending commitments (e.g. on the NHS), commentators talked of the two main parties' "political crossdressing", each trying to campaign on the other's traditional territory.[72]

Possibility of a hung Parliament

Hung Parliaments have been unusual in post-War British political history, but with the outgoing Government a coalition and opinion polls not showing a large or consistent lead for any one party, it was widely expected and predicted throughout the election campaign that no party would gain an overall majority, which could have led to a new coalition or other arrangements such as confidence and supply agreements.[73][74] This was also associated with a rise in multi-party politics, with increased support for UKIP, the SNP and the Greens.

The question of what the different parties would do in the event of a hung result dominated much of the campaign. Smaller parties focused on the power this would bring them in negotiations; Labour and the Conservatives both insisted that they were working towards winning a majority government, while they were also reported to be preparing for the possibility of a second election in the year.[75] In practice, Labour were prepared to make a "broad" offer to the Liberal Democrats in the event of a hung Parliament.[76] Most predictions saw Labour as having more potential support in Parliament than the Conservatives, with several parties, notably the SNP, having committed to keeping out a Conservative government.[77][78] The Conservatives described a potential Labour-led hung parliament as a "coalition of chaos", and David Cameron described (in a tweet) the electoral choice as one between "stable and strong government with me, or chaos with Ed Miliband".[79][80] The political turmoil in Britain in the wake of the 2015 election has since made the tweet "infamous".[80]

Conservative campaigning sought to highlight what they described as the dangers of a minority Labour administration supported by the SNP. This proved effective at dominating the agenda of the campaign[76] and at motivating voters to support them.[81][82][83][84] The Conservative victory was "widely put down to the success of the anti-Labour/SNP warnings", according to a BBC article[85] and others.[86] Labour, in reaction, produced ever stronger denials that they would co-operate with the SNP after the election.[76] The Conservatives and Lib Dems both also rejected the idea of a coalition with the SNP.[87][88][89] This was particularly notable for Labour, to whom the SNP had previously offered support: their manifesto stated that "the SNP will never put the Tories into power. Instead, if there is an anti-Tory majority after the election, we will offer to work with other parties to keep the Tories out".[90][91] SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon later confirmed in the Scottish leaders' debate on STV that she was prepared to "help make Ed Miliband prime minister".[92] However, on 26 April, Miliband ruled out a confidence and supply arrangement with the SNP too.[93] Miliband's comments suggested to many that he was working towards forming a minority government.[94][95]

The Liberal Democrats said that they would talk first to whichever party won the most seats.[96] They later campaigned on being a stabilising influence should either the Conservatives or Labour fall short of a majority, with the slogan "We will bring a heart to a Conservative Government and a brain to a Labour one".[97]

Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats ruled out coalitions with UKIP.[98] Ruth Davidson, leader of the Scottish Conservatives, asked about a deal with UKIP in the Scottish leaders' debate, replied: "No deals with UKIP." She continued that her preference and the Prime Minister's preference in a hung Parliament was for a minority Conservative government.[99] UKIP said they could have supported a minority Conservative government through a confidence and supply arrangement in return for a referendum on EU membership before Christmas 2015.[100] They also spoke of the DUP joining UKIP in this arrangement.[101] UKIP and DUP said they would work together in Parliament.[102] The DUP welcomed the possibility of a hung Parliament and the influence that this would bring them.[75] The party's deputy leader, Nigel Dodds, said the party could work with the Conservatives or Labour, but that the party is "not interested in a full-blown coalition government".[103] Their leader, Peter Robinson, said that the DUP would talk first to whichever party wins the most seats.[104] The DUP said they wanted, for their support, a commitment to 2% defence spending, a referendum on EU membership, and a reversal of the under-occupation penalty. They opposed the SNP being involved in government.[105][106] The UUP also indicated that they would not work with the SNP if it wanted another independence referendum in Scotland.[107]

The Green Party of England & Wales, Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party all ruled out working with the Conservatives, and agreed to work together "wherever possible" to counter austerity.[108][109][71] Each would also make it a condition of any agreement with Labour that Trident nuclear weapons was not replaced; the Green Party of England and Wales stated that "austerity is a red line".[110] Both Plaid Cymru and the Green Party stated a preference for a confidence and supply arrangement with Labour, rather than a coalition.[110][111] The leader of the SDLP, Alasdair McDonnell, said: "We will be the left-of-centre backbone of a Labour administration" and that "the SDLP will categorically refuse to support David Cameron and the Conservative Party".[112] Sinn Féin reiterated their abstentionist stance.[75] In the event the Conservatives did secure an overall majority, rendering much of the speculation and positioning moot.

Television debates

The first series of televised leaders' debates in the United Kingdom was held in the previous election. Following much debate and various proposals,[113][114] a seven-way debate with the leaders of Labour, the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats, UKIP, Greens, SNP and Plaid Cymru was held.[115] with a series of other debates involving some of the parties.

The campaign was notable for a reduction in the number of party posters on roadside hoardings. It was suggested that 2015 saw "the death of the campaign poster".[116]

Endorsements

Various newspapers, organisations and individuals endorsed parties or individual candidates for the election. For example, the main national newspapers gave the following endorsements:

National daily newspapers

| Newspaper | Main endorsement | Secondary endorsement(s) | Notes | Link | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Express | UK Independence Party | Conservative Party | Endorsed the UK Independence Party. | [1] | ||

| Daily Mail | Conservative Party | UK Independence Party | Supported a Conservative government. Encouraged anti-Labour tactical voting. | [2] | ||

| Liberal Democrats | ||||||

| Daily Mirror | Labour Party | Liberal Democrats | Endorsed a Labour government. Supported tactically voting LibDem against the Conservatives in marginal seats. | [3] [4] | ||

| Daily Telegraph | Conservative Party | None | [5] | |||

| Financial Times | Conservative Party | Liberal Democrats | Endorsed a Conservative-led coalition. | [6] | ||

| The Guardian | Labour Party | Green parties in the United Kingdom | Endorsed the Labour Party. Also supported Green and Liberal Democrat candidates where they were the main opposition to the Conservatives. | [7] | ||

| Liberal Democrats | ||||||

| The Independent | Liberal Democrats | Conservative Party | Endorsed a second term of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition. | [8] [9] | ||

| Metro | None | |||||

| The Sun | Conservative Party | Liberal Democrats | Supported voting for the Liberal Democrats in 14 Labour/LibDem marginals. | [10] | ||

| The Times | Conservative Party | Liberal Democrats | Endorsed a second term of Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition. | [11] | ||

National Sunday newspapers

| Newspaper | Party endorsed | Notes | Link | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent on Sunday | None | Newspaper stated in an editorial that it was not advising readers how to vote in 2015. | [12] | |

| Mail on Sunday | Conservative Party | [13] | ||

| The Observer | Labour Party | [14] | ||

| Sunday Express | UK Independence Party | [15] | ||

| Sunday Mirror | Labour Party | [16] | ||

| Sunday Telegraph | Conservative Party | [17] | ||

| Sunday Times | Conservative Party | [18] | ||

Media coverage

Despite speculation that the 2015 general election would be the 'social media election', traditional media, particularly broadcast media, remained more influential than new digital platforms.[117][118][119] A majority of the public (62%) reported that TV coverage had been most influential for informing them during the election period, especially televised debates between politicians.[120] Newspapers were next most influential, with the Daily Mail influencing people's opinions most (30%), followed by The Guardian (21%) and The Times (20%).[120] Online, major media outlets—like BBC News, newspaper websites, and Sky News—were most influential.[120] Social media was regarded less influential than radio and conversations with friends and family.[120]

During the campaign, TV news coverage was dominated by horse race journalism, focusing on the how close Labour and the Conservatives (supposedly) were according to the polls, and speculation on possible coalition outcomes.[121] This 'meta-coverage' was seen to squeeze out other content, namely policy.[121][122][123] Policy received less than half of election news airtime across all five main TV broadcasters (BBC, ITV, Channel 4, Channel 5, and Sky) during the first five weeks of the campaign.[121] When policy was addressed, the news agenda in both broadcast and print media followed the lead of the Conservative campaign,[122][124][125][126] focusing on the economy, tax, and constitutional matters (e.g., the possibility of a Labour-SNP coalition government),[126][124] with the economy dominating the news every week of the campaign.[125] On TV, these topics made up 43% of all election news coverage;[126] within the papers, nearly a third (31%) of all election-related articles were on the economy alone.[127] Within reporting and comment about the economy, newspapers prioritised Conservative party angles (i.e., spending cuts (1,351 articles), economic growth (921 articles), reducing the deficit (675 articles)) over Labour's (i.e., Zero-hour contracts (445 articles), mansion tax (339 articles), non-domicile status (322 articles)).[127] Less attention was given to policy areas that might have been problematic for the Conservatives, like the NHS or housing (policy topics favoured by Labour)[126] or immigration (favoured by UKIP).[124]

Reflecting on analysis carried out during the election campaign period, David Deacon of Loughborough University's Communication Research Centre said there was "aggressive partisanship [in] many section of the national press" which could be seen especially in the "Tory press".[122] Similarly, Steve Barnett, Professor of Communications at the University of Westminster, said that, while partisanship has always been part of British newspaper campaigning, in this election it was "more relentless and more one-sided" in favour of the Conservatives and against Labour and the other parties.[119] According to Bart Cammaerts of the Media and Communications Department at the London School of Economics, during the campaign "almost all newspapers were extremely pro-Conservative and rabidly anti-Labour".[128] 57.5% of the daily newspapers backed the Conservatives, 11.7% Labour, 4.9% UKIP, and 1.4% backed a continuation of the incumbent Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government;[129] 66% of Sunday national newspapers backed the Conservatives.[130] Of newspaper front-page lead stories, the Conservatives received 80 positive splashes and 26 negative; Labour received 30 positive against 69 negative.[125] Print media was hostile towards Labour at levels "not seen since the 1992 General Election",[124][128][131][132] when Neil Kinnock was "attacked hard and hit below the belt repeatedly".[128] Roy Greenslade described the newspaper coverage of Labour as "relentless ridicule".[133] Of the leader columns in The Sun 95% were anti-Labour.[132] The SNP also received substantial negative press in English newspapers: of the 59 leader columns about the SNP during the election, one was positive.[125] The Daily Mail ran a headline suggesting SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon was "the most dangerous woman in Britain"[124][134] and, at other times, called her a "glamorous power-dressing imperatrix" and said that she "would make Hillary Clinton look human".[127] While the Scottish edition of The Sun encouraged people north of the border to vote for the SNP, the English edition encouraged people to vote for the Conservatives in order to "stop the SNP running the country".[135] The negative coverage of the SNP increased towards the end of the election campaign.[118] While TV news airtime given to quotations from politicians was more balanced between the two larger parties (Con.: 30.14%; Lab.: 27.98%), more column space in newspapers was dedicated to quotes from Conservative politicians (44.45% versus 29.01% for Labour)[118]—according to analysts, the Conservatives "benefitted from a Tory supporting press in away the other leaders did not".[118] At times, the Conservatives worked closely with newspapers to co-ordinate their news coverage.[127] For example, The Daily Telegraph printed a letter purportedly sent directly to the paper from 5,000 small business owners; the letter had been organised by the Conservatives and prepared at Conservative Campaign Headquarters.[127]

According to researchers at Cardiff University and Loughborough University, TV news agendas focused on Conservative campaign issues partly because of editorial choices to report on news originally broken in the rightwing press but not that broken in the leftwing press.[126][122][121] Researchers also found that most airtime was given to politicians from the Conservative party—especially in Channel 4's and Channel 5's news coverage, where they received more than a third of speaking time.[121][136] Only ITV gave more airtime to Labour spokespeople (26.9% compared with 25.1% for the Conservatives).[136] Airtime given to the two main political leaders, Cameron (22.4%) and Miliband (20.9%), was more balanced than that given to their parties.[136]

Smaller parties—especially the SNP[136]—received unprecedented levels of media coverage because of speculation about a minority or coalition government.[124][126] The five most prominent politicians were David Cameron (Con) (15% of TV and press appearances), Ed Miliband (Lab) (14.7%), Nick Clegg (Lib Dem) (6.5%), Nicola Sturgeon (SNP) (5.7%), and Nigel Farage (UKIP) (5.5%).[124][126] However, according to analysts from Loughborough University Communication Research Centre, "the big winners of the media coverage were the Conservatives. They gained the most quotation time, the most strident press support, and coverage focused on their favoured issues (the economy and taxation, rather than say the NHS)".[118]

Other than politicians, 'business sources' were the most frequently quoted in the media. On the other hand, trade unions representatives, for example, received very little coverage, with business representatives receiving seven times more coverage than unions.[122] Tony Blair was also in the top ten most prominent politicians (=9), warning people about the threat of the UK leaving the EU.[124]

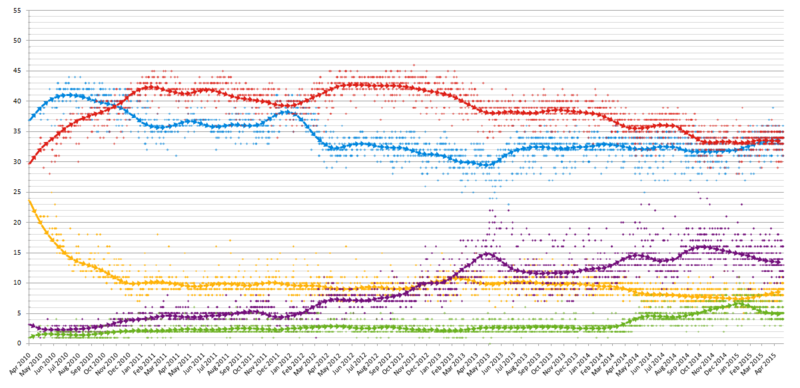

Opinion polling

Throughout the 55th parliament of the United Kingdom, first and second place in the polls without exception alternated between the Conservatives and Labour. Labour took a lead in the polls in the second half of 2010, driven in part by a collapse in Liberal Democrat support.[137] This lead rose to approximately 10 points over the Conservative Party during 2012, whose ratings dipped alongside an increase in UKIP support.[138] UKIP passed the Liberal Democrats as the third-most popular party at the start of 2013. Following this, Labour's lead over the Conservatives began to fall as UKIP gained support from it as well,[139] and by the end of the year Labour were polling at 39%, compared to 33% for the Conservative Party and 11% for UKIP.[139]

UKIP received 26.6% of the vote at the European elections in 2014, and though their support in the polls for Westminster never reached this level, it did rise up to over 15% through that year.[140] 2014 was also marked by the Scottish independence referendum. Despite the 'No' vote winning, support for the Scottish National Party rose quickly after the referendum, and had reached 43% in Scotland by the end of the year, up 23 points from the 2010 general election, largely at the expense of Labour (−16 points in Scotland) and the Liberal Democrats (−13 points).[141] In Wales, where polls were less frequent, the 2012–2014 period saw a smaller decline in Labour's lead over the second-placed Conservative Party, from 28 points to 17.[142] These votes went mainly to UKIP (+8 points) and Plaid Cymru (+2 points). The rise of UKIP and SNP, alongside the smaller increases for Plaid Cymru and the Green Party (from around 2% to 6%)[140] saw the combined support of the Conservative and Labour party fall to a record low of around 65%.[143] Within this the decline came predominantly from Labour, whose lead fell to under 2 points by the end of 2014.[140] Meanwhile, the Liberal Democrat vote, which had held at about 10% since late 2010, declined further to about 8%.[140]

Early 2015 saw the Labour lead continue to fall, disappearing by the start of March.[144] Polling during the election campaign itself remained relatively static, with the Labour and Conservative parties both polling between 33 and 34% and neither able to establish a consistent lead.[145] Support for the Green Party and UKIP showed slight drops of around 1–2 points each, while Liberal Democrat support rose up to around 9%.[146] In Scotland, support for the SNP continued to grow with polling figures in late March reaching 54%, with the Labour vote continuing to decline accordingly,[147] while Labour retained their (reduced) lead in Wales, polling at 39% by the end of the campaign, to 26% for the Conservatives, 13% for Plaid Cymru, 12% for UKIP and 6% for the Liberal Democrats.[142] The final polls showed a mixture of Conservative leads, Labour leads and ties with both between 31 and 36%, UKIP on 11–16%, the Lib Dems on 8–10%, the Greens on 4–6%, and the SNP on 4–5% of the national vote.[148]

In addition to the national polls, Lord Ashcroft funded from May 2014 a series of polls in marginal constituencies, and constituencies where minor parties were expected to be significant challengers. Among other results, Lord Ashcroft's polls suggested that the growth in SNP support would translate into more than 50 seats;[149] that there was little overall pattern in Labour and Conservative Party marginals;[150] that the Green Party MP Caroline Lucas would retain her seat;[151] that both Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg and UKIP leader Nigel Farage would face very close races to be elected in their own constituencies;[152] and that Liberal Democrat MPs would enjoy an incumbency effect that would lose fewer MPs than their national polling implied.[153] As with other smaller parties, their proportion of MPs remained likely to be considerably lower than that of total, national votes cast. Several polling companies included Ashcroft's polls in their election predictions, though several of the political parties disputed his findings.[154]

Predictions one month before the vote

The first-past-the-post system used in UK general elections means that the number of seats won is not closely related to vote share.[155] Thus, several approaches were used to convert polling data and other information into seat predictions. The table below lists some of the predictions. ElectionForecast was used by Newsnight and FiveThirtyEight. May2015.com is a project run by the New Statesman magazine.[156]

Seat predictions draw from nationwide polling, polling in the constituent nations of Britain and may additionally incorporate constituency level polling, particularly the Ashcroft polls. Approaches may or may not use uniform national swing (UNS). Approaches may just use current polling, i.e. a "nowcast" (e.g. Electoral Calculus, May2015.com and The Guardian), or add in a predictive element about how polling shifts based on historical data (e.g. ElectionForecast and Elections Etc.).[157] An alternative approach is to use the wisdom of the crowd and base a prediction on betting activity: the Spreadex and Sporting Index columns below cover bets on the number of seats each party will win with the midpoint between asking and selling price, while FirstPastThePost.net aggregates the betting predictions in each individual constituency. Some predictions cover Northern Ireland, with its distinct political culture, while others do not. Parties are sorted by current number of seats in the House of Commons:

| Party | ElectionForecast[157] (Newsnight Index) as of 9 April 2015 | Electoral Calculus[158] as of 12 April 2015 | Elections Etc.[159] as of 3 April 2015 | The Guardian[160] as of 12 April 2015 | May2015.com[161] as of 12 April 2015 | Spreadex[162] as of 15 April 2015 | Sporting Index[163] as of 12 April 2015 | First Past the Post[164] as of 12 April 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 284 | 278 | 289 | 281 | 284.5 | 267 | 283 | |

| Labour | 274 | 284 | 266 | 271 | 277 | 273.5 | 272 | 279 |

| Liberal Democrats | 28 | 17 | 22 | 29 | 26 | 24.5 | 25 | 28 |

| DUP | 8 | Included under Other | GB forecast only | Included under Other | Included under Other | No market | No market | 8.7 |

| SNP | 41 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 54 | 43.5 | 42 | 38 |

| UKIP | 1 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4.5 | 6 | 7 |

| SDLP | 3 | Included under Other | GB forecast only | Included under Other | Included under Other | No market | No market | 2.7 |

| Plaid Cymru | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3 |

| Greens | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1 |

| Other | 8 | 18 (including 18 NI seats) | GB forecast only, but above may not sum to 632 due to rounding | 18 (including 18 NI seats) | 19 (including 18 NI | No Market | No market | Respect 0.5 |

| Overall result (probability) | Hung parliament (93%) | Hung parliament (60%) | Hung parliament (80%) | Hung parliament | Hung parliament | Hung Parliament | Hung parliament | Hung parliament |

Other predictions were published.[165] An election forecasting conference on 27 March 2015 yielded 11 forecasts of the result in Great Britain (including some included in the table above).[166] Averaging the conference predictions gives Labour 283 seats, Conservatives 279, Liberal Democrats 23, UKIP 3, SNP 41, Plaid Cymru 3 and Greens 1.[167] In that situation, no two parties (excluding a Lab-Con coalition) would have been able to form a majority without the support of a third. On 27 April, Rory Scott of the bookmaker Paddy Power predicted Conservatives 284, Labour 272, SNP 50, UKIP 3, and Greens 1.[168] LucidTalk for the Belfast Telegraph predicted for Northern Ireland: DUP 9, Sinn Féin 5, SDLP 3, Sylvia Hermon 1, with the only seat change being the DUP gaining Belfast East from Alliance.[169][170]

Final predictions before the vote

Percentage shares of votes, as predicted in the first week of May:

| Party | BMG[171] | TNS-BNRB[172] | Opinium[173] | ICM[148] | YouGov[174] | Ipsos MORI[175] | Ashcroft[176] | Comres[177] | Panelbase[178] | Populus[179] | Survation[180] | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | 33.7 | 33 | 35 | 34 | 34 | 36 | 33 | 35 | 31 | 33 | 31.4 | 33.6 |

| Labour | 33.7 | 32 | 34 | 35 | 34 | 35 | 33 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 31.4 | 33.5 |

| UKIP | 12 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 16 | 14 | 15.7 | 12.7 |

| Liberal Democrats | 10 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 9.6 | 10.0 |

| Green | 4 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4.8 | 4.5 |

| SNP | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 PC | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4.7 | 4.6 |

| Other | 2.6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Lead | Tie | Con +1 | Con +1 | Lab +1 | Tie | Con +1 | Tie | Con +1 | Lab +2 | Tie | Tie | Tie |

- PC Includes Plaid Cymru

Seats predicted on 7 May:

| Party | ElectionForecast[157][181] (Newsnight Index) | Electoral Calculus[158] | Elections Etc.[182] | The Guardian[183] | May2015.com[161] | Spreadex[184] | Sporting Index[163] | First Past the Post[164] | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 278 | 280 | 285 | 273 | 288 | 286 | 279 | ||

| Labour | 267 | 274 | 262 | 273 | 268 | 266 | 269 | 270 | 269.0 |

| SNP | 53 | 52 | 53 | 52 | 56 | 48 | 46 | 49 | 51.6 |

| Liberal Democrats | 27 | 21 | 25 | 27 | 28 | 25.5 | 26.5 | 25 | 25.6 |

| DUP | 8 | Included under Other | GB forecast only | Included under Other | Included under Other | No market | No market | 8.7 | |

| UKIP | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3.25 | 3.3 | 4 | 2.5 |

| SDLP | 3 | Included under Other | GB forecast only | Included under Other | Included under Other | No market | No market | 2.7 | |

| Plaid Cymru | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3.8 | 3.35 | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| Greens | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.75 | 1.15 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| Other | Sinn Féin 5 UUP 1 Sylvia Hermon 1 Speaker 1 | 18 (including 18 NI seats) | 1, although its GB forecast only, 18 NI seats | 18 (including 18 NI seats) | 19 (including 18 NI seats & Respect 1) | No market | No market | Sinn Féin 4.7 Hermon 1 Speaker 1 UUP 1 Respect 0.6 | |

| Overall result (probability) | Hung parliament (100%[citation needed]) | Hung parliament (92%) | Hung parliament (91%) | Hung parliament | Hung parliament | Hung parliament | Hung parliament | Hung parliament | Hung parliament |

Exit poll

An exit poll, collected by Ipsos MORI and GfK on behalf of the BBC, ITN and Sky News, was published at 10 pm at the end of voting. It interviewed around 22,000 people across a sample of 133 constituencies:[185]

| Parties | Seats | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative Party | 316 |  10 10 | |

| Labour Party | 239 |  19 19 | |

| Scottish National Party | 58 |  52 52 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 10 |  47 47 | |

| UK Independence Party | 2 |  2 2 | |

| Green Party | 2 |  1 1 | |

| Others | 23 | N/A | |

| Conservatives 10 short of majority | |||

This predicted the Conservatives to be 10 seats short of an absolute majority, although with the 5 predicted Sinn Féin MPs not taking their seats, it was likely to be enough to govern. (In the event, Michelle Gildernew lost her seat, reducing the number of Sinn Féin MPs to 4.)[186]

The exit poll was markedly different from the pre-election opinion polls,[187] which had been fairly consistent; this led many pundits and MPs to speculate that the exit poll was inaccurate, and that the final result would have the two main parties closer to each other. Former Liberal Democrat leader Paddy Ashdown vowed to "eat his hat" and former Labour "spin doctor" Alastair Campbell promised to "eat his kilt" if the exit poll, which predicted huge losses for their respective parties, was right.[188]

As it turned out, the results were even more favourable to the Conservatives than the poll predicted, with the Conservatives obtaining 330 seats, an absolute majority.[189] Ashdown and Campbell were presented with hat- and kilt-shaped cakes (labelled "eat me") on BBC Question Time on 8 May.[188]

Opinion polling inaccuracies and scrutiny

With the eventual outcome in terms of both votes and seats varying substantially from the bulk of opinion polls released in the final months before the election, the polling industry received criticism for their inability to predict what was a surprisingly clear Conservative victory. Several theories have been put forward to explain the inaccuracy of the pollsters. One theory was that there had simply been a very late swing to the Conservatives, with the polling company Survation claiming that 13% of voters made up their minds in the final days and 17% on the day of the election.[190] The company also claimed that a poll they carried out a day before the election gave the Conservatives 37% and Labour 31%, though they said they did not release the poll (commissioned by the Daily Mirror) on the concern that it was too much of an outlier with other poll results.[191]

However, it was reported that pollsters had in fact picked up a late swing to Labour immediately prior to polling day, not the Conservatives.[192] It was reported after the election that private pollsters working for the two largest parties actually gathered more accurate results, with Labour's pollster James Morris claiming that the issue was largely to do with surveying technique.[193] Morris claimed that telephone polls that immediately asked for voting intentions tended to get a high "Don't know" or anti-government reaction, whereas longer telephone conversations conducted by private polls that collected other information such as views on the leaders' performances placed voters in a much better mode to give their true voting intentions.[citation needed] Another theory was the issue of 'shy Tories' not wanting to openly declare their intention to vote Conservative to pollsters.[194] A final theory, put forward after the election, was the 'Lazy Labour' factor, which claimed that Labour voters tend to not vote on polling day whereas Conservative voters have a much higher turnout.[195]

The British Polling Council announced an inquiry into the substantial variance between the opinion polls and the actual election result.[196][197] The inquiry published preliminary findings in January 2016, concluding that "the ways in which polling samples are constructed was the primary cause of the polling miss".[198] Their final report was published in March 2016.[199]

The British Election Study team have suggested that weighting error appears to be the cause.[200]

Results

After all 650 constituencies had been declared, the results were:[201]

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Leader | MPs | Votes | |||||

| Of total | Of total | |||||||

| Conservative Party | David Cameron | 330 | 50.8% | 330 / 650 | 11,299,609 | 36.8% | ||

| Labour Party | Ed Miliband | 232 | 35.7% | 232 / 650 | 9,347,273 | 30.4% | ||

| Scottish National Party | Nicola Sturgeon | 56 | 8.6% | 56 / 650 | 1,454,436 | 4.7% | ||

| Liberal Democrats | Nick Clegg | 8 | 1.2% | 8 / 650 | 2,415,916 | 7.9% | ||

| Democratic Unionist Party | Peter Robinson | 8 | 1.2% | 8 / 650 | 184,260 | 0.6% | ||

| Sinn Féin | Gerry Adams | 4 | 0.6% | 4 / 650 | 176,232 | 0.6% | ||

| Plaid Cymru | Leanne Wood | 3 | 0.5% | 3 / 650 | 181,704 | 0.6% | ||

| Social Democratic & Labour Party | Alasdair McDonnell | 3 | 0.5% | 3 / 650 | 99,809 | 0.3% | ||

| Ulster Unionist Party | Mike Nesbitt | 2 | 0.3% | 2 / 650 | 114,935 | 0.4% | ||

| UK Independence Party | Nigel Farage | 1 | 0.2% | 1 / 650 | 3,881,099 | 12.6% | ||

| Green Party of England and Wales | Natalie Bennett | 1 | 0.2% | 1 / 650 | 1,111,603 | 3.8% | ||

| Speaker | John Bercow | 1 | 0.2% | 1 / 650 | 34,617 | 0.1%[202] | ||

| Independent Unionist | Sylvia Hermon | 1 | 0.2% | 1 / 650 | 17,689 | 0.06%[203] | ||

The following table shows final election results as reported by BBC News[204] and The Guardian.[205]

| ||||||||||||||

| Political party | Leader | MPs | Votes | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidates[206] | Total | Gained | Lost | Net | Of total (%) | Total | Of total (%) | Change[b] (%) | ||||||

| Conservative[c] | David Cameron | 647 | 330 | 35 | 11 | +24 | 50.8 | 11,299,609 | 36.8 | +0.7 | ||||

| Labour | Ed Miliband | 631 | 232 | 22 | 48 | −26 | 35.7 | 9,347,273 | 30.4 | +1.5 | ||||

| UKIP | Nigel Farage | 624 | 1 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 0.2 | 3,881,099 | 12.6 | +9.5 | ||||

| Liberal Democrats | Nick Clegg | 631 | 8 | 0 | 49 | −49 | 1.2 | 2,415,916 | 7.9 | −15.1 | ||||

| SNP | Nicola Sturgeon | 59 | 56 | 50 | 0 | +50 | 8.6 | 1,454,436 | 4.7 | +3.1 | ||||

| Green Party of England and Wales | Natalie Bennett | 538 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1,111,603 | 3.8 | +2.7 | ||||

| DUP | Peter Robinson | 16 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1.2 | 184,260 | 0.6 | 0.0 | ||||

| Plaid Cymru | Leanne Wood | 40 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 181,704 | 0.6 | 0.0 | ||||

| Sinn Féin | Gerry Adams | 18 | 4 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0.6 | 176,232 | 0.6 | 0.0 | ||||

| Ulster Unionist | Mike Nesbitt | 15 | 2 | 2 | 0 | +2 | 0.3 | 114,935 | 0.4 | —[d] | ||||

| Independent | — | 170 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 101,897 | 0.3 | — | ||||

| SDLP | Alasdair McDonnell | 18 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 99,809 | 0.3 | 0.0 | ||||

| Alliance | David Ford | 18 | 0 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 61,556 | 0.2 | +0.1 | ||||

| Scottish Green | Patrick Harvie / Maggie Chapman | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 39,205 | 0.1 | 0.0 | ||||

| TUSC | Dave Nellist | 128 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36,490 | 0.1 | +0.1 | ||||

| Speaker | John Bercow | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 34,617 | 0.1 | 0.0 | ||||

| NHA[e] | Richard Taylor & Clive Peedell | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12,999 | 0.1 | 0.0 | ||||

| TUV | Jim Allister | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16,538 | 0.1 | 0.0 | ||||

| Respect | George Galloway | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9,989 | 0.0 | −0.1 | ||||

| Green (NI) | Steven Agnew | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6,822 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| CISTA | Paul Birch | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6,566 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| People Before Profit | Collective | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6,978 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Yorkshire First | Richard Carter | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6,811 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| English Democrat | Robin Tilbrook | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6,531 | 0.0 | −0.2 | ||||

| Mebyon Kernow | Dick Cole | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,675 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Lincolnshire Independent | Marianne Overton | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,407 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Liberal | Steve Radford | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,480 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Monster Raving Loony | Alan "Howling Laud" Hope | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,898 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Independent Save Withybush Save Lives | Chris Overton | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,729 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Socialist Labour | Arthur Scargill | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,481 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| CPA | Sidney Cordle | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,260 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Christian[f] | Jeff Green | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,205 | 0.0 | −0.1 | ||||

| No description[g] | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,012 | 0.0 | — | |||||

| Workers' Party | John Lowry | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2,724 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| North East | Hilton Dawson | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2,138 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Poole People | Mike Howell | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,766 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| BNP | Adam Walker | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,667 | 0.0 | −1.9 | ||||

| Residents for Uttlesford | John Lodge | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,658 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Rochdale First Party | Farooq Ahmed | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,535 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Communist | Robert David Griffiths | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,229 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Pirate | Laurence Kaye | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,130 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| National Front | Kevin Bryan | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,114 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Communities United | Kamran Malik | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,102 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Reality | Mark "Bez" Berry | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,029 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| The Southport Party | David Cobham | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 992 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| All People's Party | Prem Goyal | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 981 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Peace | John Morris | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 957 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Bournemouth Independent Alliance | David Ross | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 903 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Socialist (GB) | Collective | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 899 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Scottish Socialist | Executive Committee | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 875 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Alliance for Green Socialism | Mike Davies | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 852 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Your Vote Could Save Our Hospital | Sandra Allison | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 849 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Wigan Independents | Gareth Fairhurst | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 768 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Animal Welfare | Vanessa Hudson | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 736 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Something New | James Smith | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 695 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Consensus | Helen Tyrer | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 637 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| National Liberal | National Council | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 627 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Independents Against Social Injustice | Steve Walmsley | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 603 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Independence from Europe | Mike Nattrass | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 578 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Whig | Waleed Ghani | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 561 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Guildford Greenbelt Group | Susan Parker | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 538 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Class War | Ian Bone | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 526 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Above and Beyond | Mark Flanagan | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 522 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Northern | Mark Dawson | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 506 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Workers Revolutionary | Sheila Torrance | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 488 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Left Unity | Kate Hudson | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 455 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Liberty GB | Paul Weston | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 418 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| People First | Collective | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 407 | 0.0 | New | ||||

| Other parties[h] | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 65,537 | 0.0 | — | |||||

| Total | 3,921 | 650 | 30,697,525 | |||||||||||

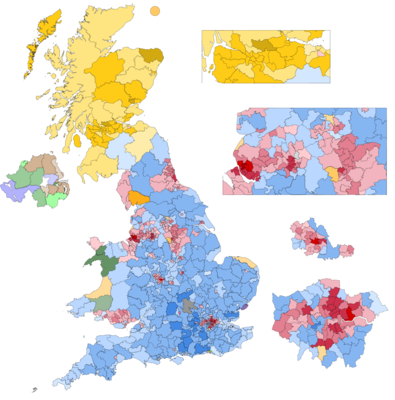

Geographic voting distribution

One result of the 2015 general election was that a different political party won the popular vote in each of the countries of the United Kingdom.[207] This was reflected in terms of MPs elected:The Conservatives won in England with 319 MPs out of 533 constituencies,[208] the SNP won in Scotland with 56 out of 59,[209] Labour won in Wales with 25 out of 40,[210] and the Democratic Unionist Party won in Northern Ireland with 8 out of 18.[211]

Outcome

Despite most opinion polls predicting that the Conservatives and Labour were neck and neck, the Conservatives secured a surprise victory after having won a clear lead over their rivals and incumbent Prime Minister David Cameron was able to form a majority single-party government with a working majority of 12 (in practice increased to 15 due to Sinn Féin's four MPs' abstention). Thus the result bore resemblance to 1992.[212] The Conservatives gained 38 seats while losing 10, all to Labour; Employment Minister Esther McVey, in Wirral West, was the most senior Conservative to lose her seat. Cameron became the first Prime Minister since Lord Salisbury in 1900 to increase his popular vote share after a full term, and is sometimes credited as being the only Prime Minister other than Margaret Thatcher (in 1983) to be re-elected with a greater number of seats for his party after a 'full term'[n 4].[213]

The Labour Party polled below expectations, winning 30.4% of the vote and 232 seats, 24 fewer than its previous result in 2010—even though in 222 constituencies there was a Conservative-to-Labour swing, as against 151 constituencies where there was a Labour-to-Conservative swing.[214] Its net loss of seats were mainly a result of its resounding defeat in Scotland, where the Scottish National Party took 40 of Labour's 41 seats, unseating key politicians such as shadow Foreign Secretary Douglas Alexander and Scottish Labour leader Jim Murphy. Labour gained some seats in London and other major cities, but lost a further nine seats to the Conservatives, recording its lowest share of the seats since the 1987 general election.[215] Ed Miliband subsequently tendered his resignation as Labour leader.

The Scottish National Party had a stunning election, rising from just 6 seats to 56 – winning all but 3 of the constituencies in Scotland and securing 50% of the popular vote in Scotland.[209] They recorded a number of record breaking swings of over 30% including the new record of 39.3% in Glasgow North East. They also won the seat of former Prime Minister Gordon Brown, overturning a majority of 23,009 to win by a majority of 9,974 votes and saw Mhairi Black, then a 20-year-old student, defeat Labour's Shadow Foreign Secretary Douglas Alexander with a swing of 26.9%.

The Liberal Democrats, who had been in government as coalition partners, suffered the worst defeat they or the previous Liberal Party had suffered since the 1970 general election.[216] Winning just eight seats, the Liberal Democrats lost their position as the UK's third party and found themselves tied in fourth place with the Democratic Unionist Party of Northern Ireland in the House of Commons, with Nick Clegg being one of the few MPs from his party to retain his seat. The Liberal Democrats gained no seats, while losing 49 in the process—of them, 27 to the Conservatives, 12 to Labour, and 10 to the SNP. The party also lost their deposit in 341 seats, the same number as in every general election from 1979 to 2010 combined.

The UK Independence Party (UKIP) was only able to hold one of its two seats, Clacton, gaining no new ones despite increasing its vote share to 12.9% (the third-highest share overall). Party leader Nigel Farage, having failed to win the constituency of South Thanet, tendered his resignation, although this was rejected by his party's executive council and he stayed on as leader.

In Northern Ireland, the Ulster Unionist Party returned to the Commons with two MPs after a five-year absence, gaining one seat from the Democratic Unionist Party and one from Sinn Féin, while the Alliance Party lost its only Commons seat to the DUP, despite an increase in total vote share.[217]

Voter demographics

Ipsos MORI

Ipsos MORI polling after the election suggested the following demographic breakdown:

| The 2015 UK General Election vote in Great Britain[218] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social group | Con | Lab | UKIP | Lib Dem | Green | Others | Lead | ||

| Total vote | 38 | 31 | 13 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 38 | 30 | 14 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 8 | ||

| Female | 37 | 33 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 4 | ||

| Age | |||||||||

| 18–24 | 27 | 43 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 16 | ||

| 25–34 | 33 | 36 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 3 | ||

| 35–44 | 35 | 35 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 0 | ||

| 45–54 | 36 | 33 | 14 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 3 | ||

| 55–64 | 37 | 31 | 14 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 6 | ||

| 65+ | 47 | 23 | 17 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 24 | ||

| Men by Age | |||||||||

| 18–24 | 32 | 41 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 9 | ||

| 25–34 | 35 | 32 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 3 | ||

| 35–54 | 38 | 32 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 6 | ||

| 55+ | 40 | 25 | 19 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 15 | ||

| Women by Age | |||||||||

| 18–24 | 24 | 44 | 10 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 20 | ||

| 25–34 | 31 | 40 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 9 | ||

| 35–54 | 32 | 35 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 3 | ||

| 55+ | 45 | 27 | 13 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 18 | ||

| Social class | |||||||||

| AB | 45 | 26 | 8 | 12 | 4 | 5 | 19 | ||

| C1 | 41 | 29 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 12 | ||

| C2 | 32 | 32 | 19 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 0 | ||

| DE | 27 | 41 | 17 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 14 | ||

| Men by social class | |||||||||

| AB | 46 | 25 | 10 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 21 | ||

| C1 | 42 | 27 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 15 | ||

| C2 | 30 | 32 | 21 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 2 | ||

| DE | 26 | 40 | 18 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 14 | ||

| Women by social class | |||||||||

| AB | 44 | 28 | 6 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 16 | ||

| C1 | 41 | 31 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 10 | ||

| C2 | 34 | 33 | 17 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 1 | ||

| DE | 28 | 42 | 16 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 14 | ||

| Housing tenure | |||||||||

| Owned | 46 | 22 | 15 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 24 | ||

| Mortgage | 39 | 31 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 8 | ||

| Social renter | 18 | 50 | 18 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 32 | ||

| Private renter | 28 | 39 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 11 | ||

| Ethnic group | |||||||||

| White | 39 | 28 | 14 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 11 | ||

| BME | 23 | 65 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 44 | ||

YouGov

YouGov polling after the election suggested the following demographic breakdown:

| The 2015 UK general election vote in Great Britain[219][220] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social group | Con | Lab | UKIP | Lib Dem | SNP | Green | Plaid | Others | Lead |

| Total vote | 38 | 31 | 13 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 37 | 29 | 15 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| Female | 38 | 33 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Age | |||||||||

| 18–29 | 32 | 36 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 30–39 | 36 | 34 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 40–49 | 33 | 33 | 14 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 50–59 | 36 | 32 | 16 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 60+ | 45 | 25 | 16 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 20 |

| Men by Age | |||||||||

| 18–29 | 34 | 31 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 30–39 | 38 | 31 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 40–49 | 34 | 31 | 16 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 50–59 | 33 | 31 | 18 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 60+ | 44 | 24 | 18 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 20 |

| Women by Age | |||||||||

| 18–29 | 29 | 41 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 12 |

| 30–39 | 33 | 37 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| 40–49 | 33 | 36 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 50–59 | 38 | 32 | 14 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| 60+ | 46 | 25 | 14 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 21 |

| Social class | |||||||||

| AB | 44 | 28 | 9 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 16 |

| C1 | 38 | 30 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| C2 | 36 | 31 | 17 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| DE | 29 | 37 | 18 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| Highest educational level | |||||||||

| GCSE or lower | 38 | 30 | 20 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| A-Level | 37 | 31 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| University | 35 | 34 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Other | 41 | 27 | 13 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 14 |

| DK/refused | 32 | 33 | 18 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Housing status | |||||||||

| Own outright | 47 | 23 | 15 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 24 |

| Mortgage | 42 | 29 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 13 |

| Social housing | 20 | 45 | 18 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 25 |

| Private rented | 34 | 32 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Don't know | 31 | 38 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Work sector | |||||||||

| Private sector | 43 | 26 | 14 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 17 |

| Public sector | 33 | 36 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Household income | |||||||||

| Under £20,000 | 29 | 36 | 17 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| £20,000-£39,999 | 37 | 32 | 14 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| £40,000-£69,999 | 42 | 29 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| £70,000+ | 51 | 23 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 28 |

| Newspaper | |||||||||

| Daily Express | 51 | 13 | 27 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 38 |

| Daily Mail | 59 | 14 | 19 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 45 |

| Daily Mirror/Daily Record | 11 | 67 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 56 |

| Daily Star | 25 | 41 | 26 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 16 |

| The Sun | 47 | 24 | 19 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 23 |

| The Daily Telegraph | 69 | 8 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 61 |

| The Guardian | 6 | 62 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 56 |

| The Independent | 17 | 47 | 4 | 16 | 3 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 30 |

| The Times | 55 | 20 | 6 | 13 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 35 |

Gender

The election led to an increase in the number of female MPs, to 191 (29% of the total, including 99 Labour; 68 Conservative; 20 SNP; 4 other) from 147 (23% of the total, including 87 Labour; 47 Conservative; 7 Liberal Democrat; 1 SNP; 5 other). As before the election, the region with the largest proportion of women MPs was North East England.[221]

Votes, of total, by party

MPs, of total, by party

Open seats changing hands

Seats which changed allegiance

111 seats changed hands compared to the result in 2010 plus three by-election gains reverted to the party that won the seat at the last general election in 2010 (Bradford West, Corby and Rochester and Strood).

General election records broken in 2015

Youngest elected MP

- Mhairi Black, Scottish National Party, elected aged 20 years 237 days.[222]

Largest swing

- A swing of 39.3% from Labour to the SNP was recorded in Glasgow North East.[223]

- Alasdair McDonnell of the SDLP won the seat of Belfast South on 24.5% of the vote.[224][225]

Aftermath

Resignations

On 8 May, three party leaders announced their resignations within an hour of each other:[226] Ed Miliband (Labour) and Nick Clegg (Liberal Democrat) resigned due to their parties' worse-than-expected results in the election, although both had been re-elected to their seats in Parliament.[227][228][229][230] Nigel Farage (UKIP) offered his resignation because he had failed to be elected as MP for Thanet South, but said he might re-stand in the resulting leadership election. However, on 11 May, the UKIP executive rejected his resignation on the grounds that the election campaign had been "a great success",[231] and Farage agreed to continue as party leader.[232]

Alan Sugar, a Labour peer in the House of Lords, also announced his resignation from the Labour Party for running what he perceived to be an anti-business campaign.[233]

In response to Labour's poor performance in Scotland, Scottish Labour leader Jim Murphy initially resisted calls for his resignation by other senior party members. Despite surviving a no-confidence vote by 17–14 from the party's national executive, Murphy announced he would step down as leader on or before 16 May.[234]

Financial markets

Financial markets reacted positively to the result, with the pound sterling rising against the Euro and US dollar when the exit poll was published, and the FTSE 100 stock market index rising 2.3% on 8 May. The BBC reported: "Bank shares saw some of the biggest gains, on hopes that the sector will not see any further rises in levies. Shares in Lloyds Banking Group rose 5.75% while Barclays was 3.7% higher", adding: "Energy firms also saw their share prices rise, as Labour had wanted a price freeze and more powers for the energy regulator. British Gas owner Centrica rose 8.1% and SSE shares were up 5.3%." BBC economics editor Robert Peston noted: "To state the obvious, investors love the Tories' general election victory. There are a few reasons. One (no surprise here) is that Labour's threat of breaking up banks and imposing energy price caps has been lifted. Second is that investors have been discounting days and weeks of wrangling after polling day over who would form the government – and so they are semi-euphoric that we already know who's in charge. Third, many investors tend to be economically Conservative and instinctively Conservative."[235]

Electoral reform