Cholangiocarcinoma, also known as bile duct cancer, is a type of cancer that forms in the bile ducts.[2] Symptoms of cholangiocarcinoma may include abdominal pain, yellowish skin, weight loss, generalized itching, and fever.[1] Light colored stool or dark urine may also occur.[4] Other biliary tract cancers include gallbladder cancer and cancer of the ampulla of Vater.[7]

| Cholangiocarcinoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bile duct cancer, cancer of the bile duct[1] |

| |

| Micrograph of an intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (right of image) adjacent to normal liver cells (left of image). H&E stain. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, yellowish skin, weight loss, generalized itching, fever[1] |

| Usual onset | 70 years old[3] |

| Types | Intrahepatic, perihilar, distal[3] |

| Risk factors | Primary sclerosing cholangitis, ulcerative colitis, infection with certain liver flukes, some congenital liver malformations[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Confirmed by examination of the tumor under a microscope[4] |

| Treatment | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, stenting procedures, liver transplantation[1] |

| Prognosis | Generally poor[5] |

| Frequency | 1–2 people per 100,000 per year (Western world)[6] |

Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma include primary sclerosing cholangitis (an inflammatory disease of the bile ducts), ulcerative colitis, cirrhosis, hepatitis C, hepatitis B, infection with certain liver flukes, and some congenital liver malformations.[1][3][8] However, most people have no identifiable risk factors.[3] The diagnosis is suspected based on a combination of blood tests, medical imaging, endoscopy, and sometimes surgical exploration.[4] The disease is confirmed by examination of cells from the tumor under a microscope.[4] It is typically an adenocarcinoma (a cancer that forms glands or secretes mucin).[3]

Cholangiocarcinoma is typically incurable at diagnosis which is why early detection is ideal.[9][1] In these cases palliative treatments may include surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and stenting procedures.[1] In about a third of cases involving the common bile duct and less commonly with other locations the tumor can be completely removed by surgery offering a chance of a cure.[1] Even when surgical removal is successful chemotherapy and radiation therapy are generally recommended.[1] In certain cases surgery may include a liver transplantation.[3] Even when surgery is successful the 5-year survival is typically less than 50%.[6]

Cholangiocarcinoma is rare in the Western world, with estimates of it occurring in 0.5–2 people per 100,000 per year.[1][6] Rates are higher in Southeast Asia where liver flukes are common.[5] Rates in parts of Thailand are 60 per 100,000 per year.[5] It typically occurs in people in their 70s; however, in those with primary sclerosing cholangitis it often occurs in the 40s.[3] Rates of cholangiocarcinoma within the liver in the Western world have increased.[6]

Signs and symptoms

The most common physical indications of cholangiocarcinoma are abnormal liver function tests, jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin occurring when bile ducts are blocked by tumor), abdominal pain (30–50%), generalized itching (66%), weight loss (30–50%), fever (up to 20%), and changes in the color of stool or urine.[10] To some extent, the symptoms depend upon the location of the tumor: people with cholangiocarcinoma in the extrahepatic bile ducts (outside the liver) are more likely to have jaundice, while those with tumors of the bile ducts within the liver more often have pain without jaundice.[11]

Blood tests of liver function in people with cholangiocarcinoma often reveal a so-called "obstructive picture", with elevated bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma glutamyl transferase levels, and relatively normal transaminase levels. Such laboratory findings suggest obstruction of the bile ducts, rather than inflammation or infection of the liver parenchyma, as the primary cause of the jaundice.[12]

Risk factors

Although most people present without any known risk factors evident, a number of risk factors for the development of cholangiocarcinoma have been described. In the Western world, the most common of these is primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), an inflammatory disease of the bile ducts which is closely associated with ulcerative colitis (UC).[13] Epidemiologic studies have suggested that the lifetime risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma for a person with PSC is on the order of 10–15%,[14] although autopsy series have found rates as high as 30% in this population.[15] For inflammatory bowel disease patients with altered DNA repair functions, the progression from PSC to cholangiocarcinoma may be a consequence of DNA damage resulting from biliary inflammation and bile acids.[16]

Certain parasitic liver diseases may be risk factors as well. Colonization with the liver flukes Opisthorchis viverrini (found in Thailand, Laos PDR, and Vietnam)[17][18][19] or Clonorchis sinensis (found in China, Taiwan, eastern Russia, Korea, and Vietnam)[20][21] has been associated with the development of cholangiocarcinoma. Control programs (Integrated Opisthorchiasis Control Program) aimed at discouraging the consumption of raw and undercooked food have been successful at reducing the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in some countries.[22] People with chronic liver disease, whether in the form of viral hepatitis (e.g. hepatitis B or hepatitis C),[23][24][25] alcoholic liver disease, or cirrhosis of the liver due to other causes, are at significantly increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma.[26][27] HIV infection was also identified in one study as a potential risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma, although it was unclear whether HIV itself or other correlated and confounding factors (e.g. hepatitis C infection) were responsible for the association.[26]

Infection with the bacteria Helicobacter bilis and Helicobacter hepaticus species can cause biliary cancer.[28]

Congenital liver abnormalities, such as Caroli disease (a specific type of five recognized choledochal cysts), have been associated with an approximately 15% lifetime risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma.[29][30] The rare inherited disorders Lynch syndrome II and biliary papillomatosis have also been found to be associated with cholangiocarcinoma.[31][32] The presence of gallstones (cholelithiasis) is not clearly associated with cholangiocarcinoma. However, intrahepatic stones (called hepatolithiasis), which are rare in the West but common in parts of Asia, have been strongly associated with cholangiocarcinoma.[33][34][35] Exposure to Thorotrast, a form of thorium dioxide which was used as a radiologic contrast medium, has been linked to the development of cholangiocarcinoma as late as 30–40 years after exposure; Thorotrast was banned in the United States in the 1950s due to its carcinogenicity.[36][37][38]

Pathophysiology

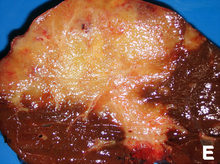

Cholangiocarcinoma can affect any area of the bile ducts, either within or outside the liver. Tumors occurring in the bile ducts within the liver are referred to as intrahepatic, those occurring in the ducts outside the liver are extrahepatic, and tumors occurring at the site where the bile ducts exit the liver may be referred to as perihilar. A cholangiocarcinoma occurring at the junction where the left and right hepatic ducts meet to form the common hepatic duct may be referred to eponymously as a Klatskin tumor.[39]

Although cholangiocarcinoma is known to have the histological and molecular features of an adenocarcinoma of epithelial cells lining the biliary tract, the actual cell of origin is unknown. Recent evidence has suggested that the initial transformed cell that generates the primary tumor may arise from a pluripotent hepatic stem cell.[40][41][42] Cholangiocarcinoma is thought to develop through a series of stages – from early hyperplasia and metaplasia, through dysplasia, to the development of frank carcinoma – in a process similar to that seen in the development of colon cancer.[43] Chronic inflammation and obstruction of the bile ducts, and the resulting impaired bile flow, are thought to play a role in this progression.[43][44][45]

Histologically, cholangiocarcinomas may vary from undifferentiated to well-differentiated. They are often surrounded by a brisk fibrotic or desmoplastic tissue response; in the presence of extensive fibrosis, it can be difficult to distinguish well-differentiated cholangiocarcinoma from normal reactive epithelium. There is no entirely specific immunohistochemical stain that can distinguish malignant from benign biliary ductal tissue, although staining for cytokeratins, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mucins may aid in diagnosis.[46] Most tumors (>90%) are adenocarcinomas.[47]

Diagnosis

Blood tests

There are no specific blood tests that can diagnose cholangiocarcinoma by themselves. Serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA19-9 are often elevated, but are not sensitive or specific enough to be used as a general screening tool. However, they may be useful in conjunction with imaging methods in supporting a suspected diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma.[48]

Abdominal imaging

Ultrasound of the liver and biliary tree is often used as the initial imaging modality in people with suspected obstructive jaundice.[49][50] Ultrasound can identify obstruction and ductal dilatation and, in some cases, may be sufficient to diagnose cholangiocarcinoma.[51] Computed tomography (CT) scanning may also play an important role in the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma.[52][53][54]

Imaging of the biliary tree

While abdominal imaging can be useful in the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, direct imaging of the bile ducts is often necessary. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), an endoscopic procedure performed by a gastroenterologist or specially trained surgeon, has been widely used for this purpose. Although ERCP is an invasive procedure with attendant risks, its advantages include the ability to obtain biopsies and to place stents or perform other interventions to relieve biliary obstruction.[12] Endoscopic ultrasound can also be performed at the time of ERCP and may increase the accuracy of the biopsy and yield information on lymph node invasion and operability.[55] As an alternative to ERCP, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) may be utilized. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a non-invasive alternative to ERCP.[56][57][58] Some authors have suggested that MRCP should supplant ERCP in the diagnosis of biliary cancers, as it may more accurately define the tumor and avoids the risks of ERCP.[59][60][61]

Surgery

Surgical exploration may be necessary to obtain a suitable biopsy and to accurately stage a person with cholangiocarcinoma. Laparoscopy can be used for staging purposes and may avoid the need for a more invasive surgical procedure, such as laparotomy, in some people.[62][63]

Pathology

Histologically, cholangiocarcinomas are classically well to moderately differentiated adenocarcinomas. Immunohistochemistry is useful in the diagnosis and may be used to help differentiate a cholangiocarcinoma from hepatocellular carcinoma and metastasis of other gastrointestinal tumors.[65] Cytological scrapings are often nondiagnostic,[66] as these tumors typically have a desmoplastic stroma and, therefore, do not release diagnostic tumor cells with scrapings.

Staging

Although there are at least three staging systems for cholangiocarcinoma (e.g. those of Bismuth, Blumgart, and the American Joint Committee on Cancer), none have been shown to be useful in predicting survival.[67] The most important staging issue is whether the tumor can be surgically removed, or whether it is too advanced for surgical treatment to be successful. Often, this determination can only be made at the time of surgery.[12]

General guidelines for operability include:[68][69]

- Absence of lymph node or liver metastases

- Absence of involvement of the portal vein

- Absence of direct invasion of adjacent organs

- Absence of widespread metastatic disease

Treatment

Cholangiocarcinoma is considered to be an incurable and rapidly lethal disease unless all the tumors can be fully resected (cut out surgically). Since the operability of the tumor can only be assessed during surgery in most cases,[70] a majority of people undergo exploratory surgery unless there is already a clear indication that the tumor is inoperable.[12] However, the Mayo Clinic has reported significant success treating early bile duct cancer with liver transplantation using a protocolized approach and strict selection criteria.[71]

Adjuvant therapy followed by liver transplantation may have a role in treatment of certain unresectable cases.[72] Locoregional therapies including transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), transarterial radioembolization (TARE) and ablation therapies have a role in intrahepatic variants of cholangiocarcinoma to provide palliation or potential cure in people who are not surgical candidates.[73]

Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy

If the tumor can be removed surgically, people may receive adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy after the operation to improve the chances of cure. If the tissue margins are negative (i.e. the tumor has been totally excised), adjuvant therapy is of uncertain benefit. Both positive[74][75] and negative[11][76][77] results have been reported with adjuvant radiation therapy in this setting, and no prospective randomized controlled trials have been conducted as of March 2007. Adjuvant chemotherapy appears to be ineffective in people with completely resected tumors.[78][79] The role of combined chemoradiotherapy in this setting is unclear. However, if the tumor tissue margins are positive, indicating that the tumor was not completely removed via surgery, then adjuvant therapy with radiation and possibly chemotherapy is generally recommended based on the available data.[80][81]

Treatment of advanced disease

The majority of cases of cholangiocarcinoma present as inoperable (unresectable) disease[82] in which case people are generally treated with palliative chemotherapy, with or without radiotherapy. Chemotherapy has been shown in a randomized controlled trial to improve quality of life and extend survival in people with inoperable cholangiocarcinoma.[83] There is no single chemotherapy regimen which is universally used, and enrollment in clinical trials is often recommended when possible.[81] Chemotherapy agents used to treat cholangiocarcinoma include 5-fluorouracil with leucovorin,[84] gemcitabine as a single agent,[85] or gemcitabine plus cisplatin,[86] irinotecan,[87] or capecitabine.[88] A small pilot study suggested possible benefit from the tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in people with advanced cholangiocarcinoma.[89]Radiation therapy appears to prolong survival in people with resected extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma,[90] and the few reports of its use in unresectable cholangiocarcinoma appear to show improved survival, but numbers are small.[6]

Infigratinib (Truseltiq) is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) that was approved for medical use in the United States in May 2021.[91] It is indicated for the treatment of people with previously treated locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma harboring an FGFR2 fusion or rearrangement.[91]

Pemigatinib (Pemazyre) is a kinase inhibitor of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) that was approved for medical use in the United States in April 2020.[92] It is indicated for the treatment of adults with previously treated, unresectable locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with a fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) fusion or other rearrangement as detected by an FDA-approved test.

Ivodesinib (Tibsovo) is a small molecule inhibitor of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1. The FDA approved ivosidenib in August 2021 for adults with previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with an isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 (IDH1) mutation as detected by an FDA-approved test.[93]

Durvalumab, (Imfinzi) is an immune checkpoint inhibitor that blocks the PD-L1 protein on the surface of immune cells, thereby allowing the immune system to recognize and attack tumor cells. In Phase III clinical trials, durvalumab, in combination with standard-of-care chemotherapy, demonstrated a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in overall survival and progression-free survival versus chemotherapy alone as a 1st-line treatment for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer.[94]

Futibatinib (Lytgobi) was approved for medical use in the United States in September 2022.[95]

Prognosis

Surgical resection offers the only potential chance of cure in cholangiocarcinoma. For non-resectable cases, the five-year survival rate is 0% where the disease is inoperable because distal lymph nodes show metastases,[96] and less than 5% in general.[97] Overall mean duration of survival is less than 6 months in people with metastatic disease.[98]

For surgical cases, the odds of cure vary depending on the tumor location and whether the tumor can be completely, or only partially, removed. Distal cholangiocarcinomas (those arising from the common bile duct) are generally treated surgically with a Whipple procedure; long-term survival rates range from 15 to 25%, although one series reported a five-year survival of 54% for people with no involvement of the lymph nodes.[99] Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (those arising from the bile ducts within the liver) are usually treated with partial hepatectomy. Various series have reported survival estimates after surgery ranging from 22 to 66%; the outcome may depend on involvement of lymph nodes and completeness of the surgery.[100] Perihilar cholangiocarcinomas (those occurring near where the bile ducts exit the liver) are least likely to be operable. When surgery is possible, they are generally treated with an aggressive approach often including removal of the gallbladder and potentially part of the liver. In patients with operable perihilar tumors, reported 5-year survival rates range from 20 to 50%.[101]

The prognosis may be worse for people with primary sclerosing cholangitis who develop cholangiocarcinoma, likely because the cancer is not detected until it is advanced.[15][102] Some evidence suggests that outcomes may be improving with more aggressive surgical approaches and adjuvant therapy.[103]

Epidemiology

| Country | IC (men/women) | EC (men/women) |

|---|---|---|

| U.S.A. | 0.60/0.43 | 0.70/0.87 |

| Japan | 0.23/0.10 | 5.87/5.20 |

| Australia | 0.70/0.53 | 0.90/1.23 |

| England/Wales | 0.83/0.63 | 0.43/0.60 |

| Scotland | 1.17/1.00 | 0.60/0.73 |

| France | 0.27/0.20 | 1.20/1.37 |

| Italy | 0.13/0.13 | 2.10/2.60 |

Cholangiocarcinoma is a relatively rare form of cancer; each year, approximately 2,000 to 3,000 new cases are diagnosed in the United States, translating into an annual incidence of 1–2 cases per 100,000 people.[105] Autopsy series have reported a prevalence of 0.01% to 0.46%.[82][106] There is a higher prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma in Asia, which has been attributed to endemic chronic parasitic infestation. The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma increases with age, and the disease is slightly more common in men than in women (possibly due to the higher rate of primary sclerosing cholangitis, a major risk factor, in men).[47] The prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma in people with primary sclerosing cholangitis may be as high as 30%, based on autopsy studies.[15]

Multiple studies have documented a steady increase in the incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; increases have been seen in North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia.[107] The reasons for the increasing occurrence of cholangiocarcinoma are unclear; improved diagnostic methods may be partially responsible, but the prevalence of potential risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma, such as HIV infection, has also been increasing during this time frame.[26]

References

External links