The Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity (Arabic: رسائل إخوان الصفا, Rasā'il Ikhwān al-ṣafā') also variously known as the Epistles of the Brethren of Sincerity, Epistles of the Brethren of Purity and Epistles of the Brethren of Purity and Loyal Friends is an Islamic encyclopedia[1] in 52 treatises (rasā'il) written by the mysterious[2] Brethren of Purity of Basra, Iraq sometime in the second half of the 10th century CE (or possibly later, in the 11th century). It had a great influence on later intellectual leading lights of the Muslim world, such as ibn Arabi,[3][4] and was transmitted as far abroad within the Muslim world as al-Andalus.[5][6]

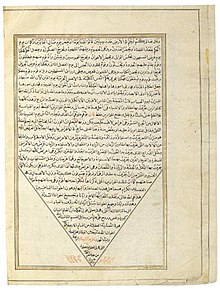

Manuscript of the Brethren's Kitab Ikhwan al-Safa i.e. the "Epistles of the Brethren of Purity". Copy created in late Safavid Iran, dated c. 17th century | |

| Author | Brethren of Purity |

|---|---|

| Original title | رسائل إخوان الصفاء وخِلَّان الوفاء |

The identity and period of the authors of the Encyclopedia have not been conclusively established,[7] though the work has been mostly linked with Isma'ilism. Idris Imad al-Din, a prominent 15th-century Isma'ili missionary in Yemen, credited the authorship of the encyclopedia to Muhammad al-Taqi, the 9th Isma'ili Imam, who lived in occultation in the era of the Abbasid Caliphate at the beginning of the Islamic Golden Age.[8]

Some suggest that besides Isma'ilism, the Brethren of Purity also contains elements of Sufism, Mu'tazilism, Nusayrism and others.[9][10][11] Some scholars present the work as Sunni Sufi.[12][13]

The subject of the work is vast and ranges from mathematics, music, astronomy, and natural sciences, to ethics, politics, religion, and magic—all compiled for one, basic purpose, that learning is training for the soul and a preparation for its eventual life once freed from the body.[14]

Turn from the sleep of negligence and the slumber of ignorance, for the world is a house of delusion and tribulations. – Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Sincerity[15]

Authorship

Authorship of the Encyclopedia is usually ascribed to the mysterious "Brethren of Purity" a group of unknown[17] scholars placed in Basra, Iraq sometime around 10th century CE .[18][19] While it is generally accepted that it was the group who authored at least the 52 rasa'il,[20] the authorship of the "Summary" (al-Risalat al-Jami'a) is uncertain; it has been ascribed to the later Majriti but this has been disproved by Yves Marquet (see the Risalat al-Jami'a section).Since style of the text is plain, and there are numerous ambiguities, due to language and vocabulary, often of Persian origin.[21]

Some philosophers and historians such as Tawhidi, Ibn al-Qifti, Shahrazuri disclosed the names of those allegedly involved in the development of the work: Abu Sulayma Bisti, Muqaddasi, 'Ali ibn Harun, Zanjani, Muahmmad ibn Ahmad Narhruji, 'Awfi. All these people are according to Henry Corbin, Ismailis[22] Other scholars, such as Susanne Diwald and Abdul Latif Tibawi have asserted a Sunni-Sufi nature of the work.[12][13]

Further perplexities abound; the use of pronouns for the authorial "sender" of the rasa'il is not consistent, with the writer occasionally slipping from third person to first-person (for example, in Epistle 44, "The Doctrine of the Sincere Brethren").[23] This has led some to suggest that the rasa'il were not in fact written co-operatively by a group or consolidated notes from lectures and discussions, but were actually the work of a single person.[24] Of course, if one accepts the longer time spans proposed for the composition of the Encyclopedia, or the simpler possibility that each risala was written by a separate person, sole authorship would be impossible.

Contents

The subject matter of the Rasa'il is vast and ranges from mathematics, music, logic, astronomy, the physical and natural sciences, as well as exploring the nature of the soul and investigating associated matters in ethics, revelation, and spirituality.[9][25]

Its philosophical outlook was Neoplatonic and it tried to integrate Greek philosophy (and especially the dialectical reasoning and logic of Aristotelianism) with various astrological, Hermetic, Gnostic and Islamic schools of thought. Scholars have seen Ismaili[26] and Sufi influences in the religious content, and Mu'tazilite acceptance of reasoning in the work.[10] Others, however, hold the Brethren to be "free-thinkers" who transcended sectarian divisions and were not bound by the doctrines of any specific creed.[9]

Their unabashed eclecticism[27] is fairly unusual in this period of Arabic thought, characterised by fierce theological disputes; they refused to condemn rival schools of thought or religions, instead insisting that they be examined fairly and open-mindedly for what truth they may contain:

...to shun no science, scorn any book, or to cling fanatically to no single creed. For [their] own creed encompasses all the others and comprehends all the sciences generally. This creed is the consideration of all existing things, both sensible and intelligible, from beginning to end, whether hidden or overt, manifest or obscure . . . in so far as they all derive from a single principle, a single cause, a single world, and a single Soul." - (from the Ikhwan al-Safa, or Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity; Rasa'il IV, pg 52) [15]

In total, they cover most of the areas an educated person was expected to understand in that era. The epistles (or "rasa'il") generally increase in abstractness, finally dealing with the Brethren's somewhat pantheistic philosophy, in which each soul is an emanation, a fragment of a universal soul with which it will reunite at death;[28] in turn, the universal soul will reunite with Allah on Doomsday. The epistles are intended to transmit right knowledge, leading to harmony with the universe and happiness.

Organization

Organizationally, it is divided into 52 epistles. The 52 rasa'il are subdivided into four sections, sometimes called books (indeed, some complete editions of the Encyclopedia are in four volumes); in order, they are: 14 on the Mathematical Sciences, 17 on the Natural Sciences, 10 on the Psychological and Rational Sciences, 11 on Theological Sciences.[25]

The division into four sections is no accident; the number four held great importance in Neoplatonic numerology, being the first square number and for being even. Reputedly, Pythagoras held that a man's life was divided into four sections, much like a year was divided into four seasons. The Brethren divided mathematics itself into four sections: arithmetic was Pythagoras and Nicomachus' domain; Ptolemy ruled over astronomy with his Almagest; geometry was associated with Euclid, naturally; and the fourth and last division was that of music. The fours did not cease there- the Brethren observed that four was crucial to a decimal system, as

Another possibility, suggested by Netton is that the veneration for four stems instead from the Brethren's great interest in the Corpus Hermeticum of Hermes Trismegistus (identified with the god Hermes, to whom the number four was sacred); that hermetic tradition's magical lore was the main subject of the 51st rasa'il.

Netton mentions that there are suggestions that the 52nd risalah (on talismans and magic) is a later addition to the Encyclopedia, because of intertextual evidence: a number of the rasa'il claim that the total of rasa'il is 51. However, the 52nd risalah itself claims to be number 51 in one area, and number 52 in another, leading to the possibility that the Brethren's attraction for the number 51 (or 17 times 3; there were 17 rasa'il on natural sciences) is responsible for the confusion. Seyyed Hossein Nasr suggests that the origin of the preference for 17 stemmed from the alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān's numerological symbolism.

Risalat al-Jami'a

Besides the fifty-odd epistles, there exists what claims to be overarching summary of the work, which is not counted in the 52, called "The Summary" (al-Risalat al-Jami'a) which exists in two versions. It has been claimed to have been the work of Majriti (d. circa 1008), although Netton states Majriti could not have composed it, and that Yves Marquet concludes from a philological analysis of the vocabulary and style in his La Philosophie des Ihwan al-Safa (1975) that it had to have been composed at the same time as the main corpus.

Style

Like conventional Arabic Islamic works, the Epistles have no lack of time-worn honorifics and quotations from the Qur'an,[30] but the Encyclopedia is also famous for some of the didactic fables it sprinkled throughout the text; a particular one, the "Island of Animals" or the "Debate of Animals" (embedded within the 22nd rasa'il, titled "On How The Animals and their Kinds are Formed"), is one of the most popular animal fables in Islam. The fable concerns how 70 men, nearly shipwrecked, discover an island where animals ruled, and began to settle on it. They oppressed and killed the animals, who unused to such harsh treatment, complained to the King (or Shah) of Djinns. The King arranged a series of debates between the humans and various representatives of the animals, such as the nightingale, the bee, and the jackal. The animals nearly defeat the humans, but an Arabian ends the series by pointing out that there was one way in which humans were superior to animals and so worthy of making animals their servants: they were the only ones Allah had offered the chance of eternal life to. The King was convinced by this argument, and granted his judgement to them, but strongly cautioned them that the same Qur'an that supported them also promised them hellfire should they mistreat their animals.

Philosophy

More metaphysical were the four ranks (or "spiritual principles"), which apparently were an elaboration of Plotinus' triad of Thought, Soul, and the One, known to the Brethren through The Theology of Aristotle (a version of Plotinus' Enneads in Arabic, modified with changes and paraphrases, and attributed to Aristotle);[31] first, the Creator (al-Bārī) emanated down to Universal Intellect (al-'Aql al-Kullī), then to Universal Soul (al-Nafs), and through Prime Matter (al-Hayūlā al-Ūlā), which emanated still further down through (and creating) the mundane hierarchy. The mundane hierarchy consisted of Nature (al-Tabī'a), the Absolute Body (al-Jism al-Mutlaq), the Sphere (al-Falak), the Four Elements (al-Arkān), and the Beings of this world (al-Muwalladāt) in their three varieties of animals, minerals, and vegetables, for a total hierarchy of nine members. Furthermore, each member increased in subdivisions proportional to how far down in the hierarchy it was, for instance, Sphere, being number seven has the seven planets as its members.

The Absolute Body is also a form in Prime Matter as we explained in the Chapter on Matter. Prime Matter is a spiritual form which emanated from the Universal Soul. The Universal Soul also is a spiritual form which emanated from the Universal Intellect which is the first thing the Creator Created."[32] Not all Pythagorean doctrines were followed, however. The Brethren argued strenuously against transmigration of the soul. Since they refused to accept transmigration, then the Platonic idea that all learning is "remembrance" and that man can never attain to complete knowledge whilst shackled in his body must be false; the Brethren's stance was rather that a person could potentially learn everything worth knowing and avoid the snares and delusion of this sinful world, eventually attaining to Paradise, Allah, and salvation, but unless they studied wise men and wise books - like their encyclopedia, whose sole purpose was to entice men to learn its knowledge and possibly be saved - that possibility would never become an actuality. As Netton writes, "The magpie eclecticism with which they surveyed and utilized elements from the philosophies of Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle and Plotinus, and religions such as Nestorian Christianity, Judaism and Hinduism,[23] was not an early attempt at ecumenism or interfaith dialogue. Their accumulation of knowledge was ordered towards the sublime goal of salvation. To use their own image, they perceived their Brotherhood, to which they invited others, as a "Ship of Salvation" that would float free from the sea of matter; the Ikhwan, with their doctrines of mutual cooperation, asceticism, and righteous living, would reach the gates of Paradise in its care."[33]

Another area in which the Brethren differed was in their conceptions of nature, in which they rejected the emanation of Forms that characterized Platonic philosophy for a quasi-Aristotelian system of substances:

Know, O brother, that the scholars have said that all things are of two types, substances and accidents, and that all substances are of one kind and self-existent, while accidents are of nine kinds, present in the substances, and they are attributes of them. But the Creator may not be described as either accident or substance, for He is their Creator and efficient cause.[34]

The first thing which the Creator produced and called into existence is a simple, spiritual, extremely perfect and excellent substance in which the form of all things is contained. This substance is called the Intellect. From this substance proceeds a second one which in hierarchy is below the first and is called the Universal Soul (al-nafs al-kullīyah). From the Universal Soul proceeds another substance which is below the Soul and which is called Original Matter. The latter is transformed into the Absolute Body, that is, into Secondary Matter which has length, width and depth."[35]

The 14th edition (EB-2:187a; 14th Ed., 1930) of the Encyclopædia Britannica described the mingling of Neoplatonism and Aristotelianism this way:

The materials of the work come chiefly from Aristotle, but they are conceived of in a Platonizing spirit, which places as the bond of all things a universal soul of the world with its partial or fragmentary souls."[11]

Evolution

The text in the "Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity" describes biological diversity in a manner similar to the modern day theory of evolution. The contexts of such passages are interpreted differently by scholars. The Brethren view as a proof on pre-Darwinian evolution theory also has been criticized by some scholars.[36]

In this document some modern day scholars note that “chain of being described by the Ikhwan possess a temporal aspect which has led certain scholars to view that the authors of the Rasai’l believed in the modern theory of evolution”.[37] According to the Rasa’il “But individuals are in perpetual flow; they are neither definite nor preserved. The reason for the conservation of forms, genus and species in matter is fixity of their celestial cause because their efficient cause is the Universal Soul of the spheres instead of the change and continuous flux of individuals which is due to the variability of their cause”.[38] This statement is supporting the concept that species and individuals are not static, and that when they change it is due to a new purpose given. In the Ikhwan doctrine there are similarities between that and the theory of evolution. Both believe that “the time of existence of terrestrial plants precedes that of animals, minerals precede plants, and organism adapt to their environment”,[39] but asserts that everything exists for a purpose.

Muhammad Hamidullah describes the ideas on evolution found in the Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity (The Epistles of Ikhwan al-Safa) as follows:

"[These books] state that God first created matter and invested it with energy for development. Matter, therefore, adopted the form of vapour which assumed the shape of water in due time. The next stage of development was mineral life. Different kinds of stones developed in course of time. Their highest form being mirjan (coral). It is a stone which has in it branches like those of a tree. After mineral life evolves vegetation. The evolution of vegetation culminates with a tree which bears the qualities of an animal. This is the date-palm. It has male and female genders. It does not wither if all its branches are chopped but it dies when the head is cut off. The date-palm is therefore considered the highest among the trees and resembles the lowest among animals. Then is born the lowest of animals. It evolves into an ape. This is not the statement of Darwin. This is what Ibn Maskawayh states and this is precisely what is written in the Epistles of Ikhwan al-Safa. The Muslim thinkers state that ape then evolved into a lower kind of a barbarian man. He then became a superior human being. Man becomes a saint, a prophet. He evolves into a higher stage and becomes an angel. The one higher to angels is indeed none but God. Everything begins from Him and everything returns to Him."[40]

English translations of the Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity were available from 1812, hence this work may have had an influence on Charles Darwin and his inception of Darwinism.[40] However Hamidullah's "Darwin was inspired by the Epistles of the Ihkwan al-Safa" theory sounds unlikely as Charles Darwin comes from an evolutionist family with his well-known physician grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, author of the poem The Origin of Society on evolution, was one of the leading Enlightenment evolutionists.[41]

Literature

The 48th epistle of the Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity features a fictional Arabic narrative. It is an anecdote of a "prince who strays from his palace during his wedding feast and, drunk, spends the night in a cemetery, confusing a corpse with his bride. The story is used as a gnostic parable of the soul's pre-existence and return from its terrestrial sojourn".[42]

Editions and translations

Complete editions of the encyclopedia have been printed at least three times:[43]

- Kitāb Ikhwān al-Ṣafā' (edited by Wilayat Husayn, Bombay 1888)

- Rasā'il Ikhwān al-Ṣafā' (edited by Khayr al-din al-Zarkali with introductions by Tāha Ḥusayn and Aḥmad Zakī Pasha, in 4 volumes, Cairo 1928)

- Rasā'il Ikhwān al-Ṣafā' (4 volumes, Beirut: Dār Ṣādir 1957)

The Encyclopedia has been widely translated, appearing not merely in its original Arabic, but in German, English, Persian, Turkish, and Hindustani.[4] Although portions of the Encyclopedia were translated into English as early as 1812, with the Rev. T. Thomason's prose English introduction to Shaikh Ahmad b. Muhammed Shurwan's Arabic edition of the "Debate of Animals" published in Calcutta,[24] a complete translation of the Encyclopedia into English does not exist as of 2006, although Friedrich Dieterici (Professor of Arabic in Berlin) translated the first 40 of the epistles into German;[44] presumably, the remainder have since been translated. The "Island of Animals" have been translated several times in differing completion;[45] the fifth risalah, on music, has been translated into English[46] as have the 43rd through the 47th epistles.[47]

As of 2021[update], the first complete Arabic critical edition and annotated English translation of the Rasa’il Ikhwan al-Safa’, with English commentaries, is being published by Oxford University Press in association with London's Institute of Ismaili Studies. The series' General Editor is Nader El-Bizri.[48] This series began in 2008 with an introductory volume of studies edited by Nader El-Bizri, and continued with the publication of:[49]

- Epistle 22: The Case of the Animals versus Man Before the King of the Jinn (eds. trans. L. Goodman & R. McGregor)

- Epistle 5: On Music (ed. trans. O. Wright, 2010)

- Epistles 10–15: On Logic (ed. trans. C. Baffioni, 2010)

- Epistle 52a: On Magic, Part I (eds. trans. G. de Callatay & B. Halflants, 2011)

- Epistles 1–2: Arithmetic and Geometry (ed. trans. N. El-Bizri, 2012)

- Epistles 15–21: Natural Sciences (ed. trans. C. Baffioni, 2013)

- Epistle 4: Geography (ed. trans. I Sanchez and J. Montgomery, 2014)

- Epistle 3: On "Astronomia" (ed. trans. J. F. Ragep and T. Mimura, 2015)

- Epistles 32–36: Sciences of the Soul and Intellect, Part I (ed. trans. I. Poonawala, G. de Callatay, P. Walker, D. Simonowitz, 2015)

- Epistles 39–41: Sciences of the Soul and Intellect, Part III (2017)

- Epistles 43–45: On Companionship and Belief (2017)

- Epistles 6–8: On Composition and the Arts (Nader El-Bizri, 2018)

- Epistle 48: The Call to God (Abbas Hamdani and Abdallah Soufan, 2019)

- Epistles 49–51: On God and the World (Wilferd Madelung, 2019)

- Epistles 29–31: On Life, Death, and Languages (Eric Ormsby, 2021)

Both the editors' approach to the project and the quality of its English translations have been criticized.[50]

See also

Notes

References

- Lane-Poole, Stanley (1966) [1883], Studies in a Mosque (1st ed.), Beirut: Khayat Book & Publishing Company S.A.L.; based on Dieterici's outline and translations.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (1964), An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines: Conceptions of nature and methods used for its study by the Ihwan Al-Safa, Al-Biruni, and Ibn Sina, Boston, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, LCCN 64-13430

- Van Reijn, Eric (1995), The Epistles of the Sincere Brethren: an annotated translation of Epistles 43-47, vol. 1 (1st ed.), Minerva Press, ISBN 1-85863-418-0; a partial translation

- Netton, Ian Richard (1991), Muslim Neoplatonists: An Introduction to the Thought of the Brethren of Purity, vol. 1 (1st ed.), Edinburgh, England: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0-7486-0251-8

- Ivanov, Valdimir Alekseevich (1946), The Alleged Founder of Ismailism., The Ismaili Society series; no. 1; Variation: Ismaili Society, Bombay; Ismaili Society series; no. 1., Bombay, Pub. for the Ismaili Society by Thacker, p. 197, LCCN 48-3517, OCLC: 385503

- Ikhwan as-Safa and their Rasa'il: A Critical Review of a Century and a Half of Research, by A. L. Tibawi, published in volume 2 of The Islamic Quarterly in 1955

- Rasa'il Ikhwan al-Safa', vol. 4, Beirut: Dar Sadir

- Johnson-Davies, Denys (1994), The Island of Animals / Khemir, Sabiha; (Illustrator - Ill.), Austin: University of Texas Press, p. 76, ISBN 0-292-74035-2

- "Notices of some copies of the Arabic work entitled "Rasàyil Ikhwàm al-cafâ"", written by Aloys Sprenger, originally published by the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (in Calcutta) in 1848 [2]

- "Abū Ḥayyan Al-Tawḥīdī and The Brethren of Purity", Abbas Hamdani. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 9 (1978), 345-353

Further reading

- (in French) La philosophie des Ihwan al-Safa' ("The philosophy of the Brethren of Purity"), Yves Marquet, 1975. Published in Algiers by the Société Nationale d'Édition et de Diffusion

- Epistles of the Brethren of Purity. The Ikhwan al-Safa' and their Rasa'il, ed. Nader El-Bizri (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

External links

- Article at Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Ikhwan al-Safa'". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Ikhwān al-Safā’[permanent dead link] - (general encyclopedia-style article)

- The Rasail Ikhwan as-Safa

- "Ikhwan al-Safa by Omar A. Farrukh" from A History of Muslim Philosophy [3]

- Review of Yves Marquet's La philosophie des Ihwan al-Safa': de Dieu a l'homme by F. W. Zimmermann

- "The Classification of the Sciences according to the Rasa'il Ikhwan al-Safa'" by Godefroid de Callataÿ Archived 2013-05-12 at the Wayback Machine

- The Institute of Ismaili Studies article on the Brethren, by Nader El-Bizri Archived 2014-05-29 at the Wayback Machine

- The Institute of Ismaili Studies gallery of images of manuscripts of the Rasa’il of the Ikhwan al-Safa’ Archived 2014-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- "Beastly Colloquies: Of Plagiarism and Pluralism in Two Medieval Disputations Between Animals and Men" -(by Lourdes María Alvarez; a discussion of the animal fables and later imitators; PDF file)

- "Pages of Medieval Mideastern History" - (by Eloise Hart; covers various small scholarly groups influential in the Arabic world)

- "Ikhwanus Safa: A Rational and Liberal Approach to Islam" - (by Asghar Ali Engineer)

- "Mark Swaney on the History of Magic Squares" -(includes a discussion of magic squares and the Encyclopedia)