Gaulish is an extinct Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium, most of Switzerland, Northern Italy, as well as the parts of the Netherlands and Germany on the west bank of the Rhine). In a wider sense, it also comprises varieties of Celtic that were spoken across much of central Europe ("Noric"), parts of the Balkans, and Anatolia ("Galatian"), which are thought to have been closely related.[1][2] The more divergent Lepontic of Northern Italy has also sometimes been subsumed under Gaulish.[3][4]

| Gaulish | |

|---|---|

| Region | Gaul |

| Ethnicity | Gauls |

| Extinct | 6th century AD |

| Old Italic, Greek, Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:xtg – Transalpine Gaulishxga – Galatianxcg – ?Cisalpine Gaulishxlp – ?Lepontic |

xtg Transalpine Gaulish | |

xga Galatian | |

xcg ?Cisalpine Gaulish | |

xlp ?Lepontic | |

| Glottolog | tran1282 Transalpine Gaulish |

Together with Lepontic and the Celtiberian spoken in the Iberian Peninsula, Gaulish is a member of the geographic group of Continental Celtic languages. The precise linguistic relationships among them, as well as between them and the modern Insular Celtic languages, are uncertain and a matter of ongoing debate because of their sparse attestation.

Gaulish is found in some 800 (often fragmentary) inscriptions including calendars, pottery accounts, funeral monuments, short dedications to gods, coin inscriptions, statements of ownership, and other texts, possibly curse tablets. Gaulish was first written in Greek script in southern France and in a variety of Old Italic script in northern Italy. After the Roman conquest of those regions, writing shifted to Latin script.[5] During his conquest of Gaul, Caesar reported that the Helvetii were in possession of documents in the Greek script, and all Gaulish coins used the Greek script until about 50 BCE.[6]

Gaulish in Western Europe was supplanted by Vulgar Latin[7] and various Germanic languages from around the 5th century CE onward. It is thought to have been a living language well into the 6th century.[8]

The legacy of Gaulish can be observed in the modern French language, in which 150-400 words are derived from the extinct Celtic language. Some of these words have also found their way into the English language through the influence of Norman French.

Classification

It is estimated that during the Bronze Age, Proto-Celtic started splitting into distinct languages, including Celtiberian and Gaulish.[9] Due to the expansion of Celtic tribes in the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, closely related forms of Celtic came to be spoken in a vast arc extending from Britain and France through the Alpine region and Pannonia in central Europe, and into parts of the Balkans and Anatolia. Their precise linguistic relationships are uncertain due to fragmentary evidence.

The Gaulish varieties of central and eastern Europe and of Anatolia (called Noric and Galatian, respectively) are barely attested, but from what little is known of them it appears that they were quite similar to those of Gaul and can be considered dialects of a single language.[1] Among those regions where substantial inscriptional evidence exists, three varieties are usually distinguished.

- Lepontic, attested from a small area on the south slopes of the Alps, near the modern Swiss town of Lugano, is the oldest Celtic language known to have been written, with inscriptions in a variant of Old Italic script appearing circa 600. It has been described as either an "early dialect of an outlying form of Gaulish" or a separate Continental Celtic language.[10]

- Attestations of Gaulish proper in present-day France are called "Transalpine Gaulish." Its written record begins in the 3rd century BCE with inscriptions in Greek script, found mainly in the Rhône area of southern France, where Greek cultural influence was present via the colony of Massilia, founded circa 600 BCE. After the Roman conquest of Gaul (58–50 BCE), the writing of Gaulish shifted to Latin script.

- Finally, there are a small number of inscriptions from the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE in Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy), which share the same archaic alphabet as the Lepontic inscriptions but are found outside the Lepontic area proper. As they were written after the Gallic conquest of Cisalpine Gaul, they are usually called "Cisalpine Gaulish". They share some linguistic features both with Lepontic and with Transalpine Gaulish; for instance, both Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish simplify the consonant clusters -nd- and -χs- to -nn- and -ss- respectively, while both Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaulish replace inherited word-final -m with -n.[11] Scholars have debated to what extent the distinctive features of Lepontic reflect merely its earlier origin or a genuine genealogical split, and to what extent Cisalpine Gaulish should be seen as a continuation of Lepontic or an independent offshoot of mainstream Transalpine Gaulish.

The relationship between Gaulish and the other Celtic languages is also debated. Most scholars today agree that Celtiberian was the first to branch off from other Celtic.[12] Gaulish, situated in the centre of the Celtic language area, shares with the neighboring Brittonic languages of Britain, as well as the neighboring Italic Osco-Umbrian languages, the change of the Indo-European labialized voiceless velar stop /kʷ/ > /p/, while both Celtiberian in the south and Goidelic in Ireland retain /kʷ/. Taking this as the primary genealogical isogloss, some scholars divide the Celtic languages into a "q-Celtic" group and a "p-Celtic" group, in which the p-Celtic languages Gaulish and Brittonic form a common "Gallo-Brittonic" branch. Other scholars place more emphasis on shared innovations between Brittonic and Goidelic and group these together as an Insular Celtic branch. Sims-Williams (2007) discusses a composite model, in which the Continental and Insular varieties are seen as part of a dialect continuum, with genealogical splits and areal innovations intersecting.[13]

History

Early period

Though Gaulish personal names written by Gauls in Greek script are attested from the region surrounding Massalia by the 3rd century BCE, the first true inscriptions in Gaulish appeared in the 2nd century BCE.[14][15]

At least 13 references to Gaulish speech and Gaulish writing can be found in Greek and Latin writers of antiquity. The word "Gaulish" (gallicum) as a language term is first explicitly used in the Appendix Vergiliana in a poem referring to Gaulish letters of the alphabet.[16] Julius Caesar says in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico of 58 BCE that the Celts/Gauls and their language are separated from the neighboring Aquitani and Belgae by the rivers Garonne and Seine/Marne, respectively.[17] Caesar relates that census accounts written in Greek script were found among the Helvetii.[18] He also notes that as of 53 BCE the Gaulish druids used the Greek alphabet for private and public transactions, with the important exception of druidic doctrines, which could only be memorised and were not allowed to be written down.[19] According to the Recueil des Inscriptions Gauloises, nearly three quarters of Gaulish inscriptions (disregarding coins) are in the Greek alphabet. Later inscriptions dating to Roman Gaul are mostly in Latin alphabet and have been found principally in central France.[20]

Roman period

Latin was quickly adopted by the Gaulish aristocracy after Roman conquest to maintain their elite power and influence,[21] trilingualism in southern Gaul being noted as early as the 1st century BCE.[22]

Early references to Gaulish in Gaul tend to be made in the context of problems with Greek or Latin fluency until around CE 400, whereas after c. 450, Gaulish begins to be mentioned in contexts where Latin has replaced "Gaulish" or "Celtic" (whatever the authors meant by those terms), though at first these only concerned the upper classes. For Galatia (Anatolia), there is no source explicitly indicating a 5th-century language replacement:

- During the last quarter of the 2nd century, Irenaeus, bishop of Lugdunum (present-day Lyon), apologises for his inadequate Greek, being "resident among the Keltae and accustomed for the most part to use a barbarous dialect".[23]

- According to the Vita Sancti Symphoriani, Symphorian of Augustodunum (present-day Autun) was executed on 22 August 178 for his Christian faith. While he was being led to his execution, "his venerable mother admonished him from the wall assiduously and notable to all (?), saying in the Gaulish speech: Son, son, Symphorianus, think of your God!" (uenerabilis mater sua de muro sedula et nota illum uoce Gallica monuit dicens: 'nate, nate Synforiane, mentobeto to diuo'[24]). The Gaulish sentence has been transmitted in a corrupt state in the various manuscripts; as it stands, it has been reconstructed by Thurneysen. According to David Stifter (2012), *mentobeto looks like a Proto-Romance verb derived from Latin mens, mentis ‘mind’ and habere ‘to have’, and it cannot be excluded that the whole utterance is an early variant of Romance, or a mixture of Romance and Gaulish, instead of being an instance of pure Gaulish. On the other hand, nate is attested in Gaulish (for example in Endlicher's Glossary[25]), and the author of the Vita Sancti Symphoriani, whether or not fluent in Gaulish, evidently expects a non-Latin language to have been spoken at the time.

- The Latin author Aulus Gellius (c. 180) mentions Gaulish alongside the Etruscan language in one anecdote, indicating that his listeners had heard of these languages, but would not understand a word of either.[26]

- The Roman History by Cassius Dio (written CE 207–229) may imply that Cis- and Transalpine Gauls spoke the same language, as can be deduced from the following passages: (1) Book XIII mentions the principle that named tribes have a common government and a common speech, otherwise the population of a region is summarized by a geographic term, as in the case of the Spanish/Iberians.[27] (2) In Books XII and XIV, Gauls between the Pyrenees and the River Po are stated to consider themselves kinsmen.[28][29] (3) In Book XLVI, Cassius Dio explains that the defining difference between Cis- and Transalpine Gauls is the length of hair and the style of clothes (i.e., he does not mention any language difference), the Cisalpine Gauls having adopted shorter hair and the Roman toga at an early date (Gallia Togata).[30] Potentially in contrast, Caesar described the river Rhone as a frontier between the Celts and provincia nostra.[17]

- In the Digesta XXXII, 11 of Ulpian (CE 222–228) it is decreed that fideicommissa (testamentary provisions) may also be composed in Gaulish.[31]

- Writing at some point between c. CE 378 and CE 395, Latin poet and scholar Decimus Magnus Ausonius, from Burdigala (now Bordeaux), characterizes his deceased father Iulius' ability to speak Latin as inpromptus, "halting, not fluent"; in Attic Greek, Iulius felt eloquent enough.[32] This remark is sometimes taken as indicating that the first language of Iulius Ausonius (c. CE 290–378) was Gaulish,[33] but may alternatively mean his first language was Greek. As a physician, he would have cultivated Greek as part of his professional proficiency.

- In the Dialogi de Vita Martini I, 26 by Sulpicius Severus (CE 363–425), one of the partners in the dialogue utters the rhetorical commonplace that his deficient Latin might insult the ears of his partners. One of them answers: uel Celtice aut si mauis Gallice loquere dummodo Martinum loquaris ‘speak Celtic or, if you prefer, Gaulish, as long as you speak about Martin’.[34]

- Saint Jerome (writing in CE 386/387) remarked in a commentary on St. Paul's Epistle to the Galatians that the Belgic Treveri spoke almost the same language as the Galatians, rather than Latin.[35] This agrees with an earlier report in CE by Lucian.[36]

- In an CE 474 letter to his brother-in-law, Sidonius Apollinaris, bishop of Clermont in Auvergne, says that in his younger years, "our nobles ... resolved to forsake the barbarous Celtic dialect", evidently in favour of eloquent Latin.[37]

Late Roman

- Cassiodorus (ca. 490–585) cites in his book Variae VIII, 12, 7 (dated 526) from a letter to king Athalaric: Romanum denique eloquium non suis regionibus inuenisti et ibi te Tulliana lectio disertum reddidit, ubi quondam Gallica lingua resonauit ‘Finally you found Roman eloquence in regions that were not originally its own; and there the reading of Cicero rendered you eloquent where once the Gaulish language resounded’[38]

- In the 6th century, Cyril of Scythopolis (CE 525–559) tells a story about a Galatian monk who was possessed by an evil spirit and was unable to speak, but if forced to, could speak only in Galatian.[39]

- Gregory of Tours wrote in the 6th century (c. 560–575) that a shrine in Auvergne which "is called Vasso Galatae in the Gallic tongue" was destroyed and burnt to the ground.[40] This quote has been held by historical linguistic scholarship to attest that Gaulish was indeed still spoken as late as the mid- to late 6th century in France.[8][41]

Final demise

Despite considerable Romanization of the local material culture, the Gaulish language is held to have survived and coexisted with spoken Latin during the centuries of Roman rule of Gaul.[8] The exact time of the final extinction of Gaulish is unknown, but it is estimated to have been about the sixth century CE.[42]

The language shift was uneven in its progress and shaped by sociological factors. Although there was a presence of retired veterans in colonies, these did not significantly alter the linguistic composition of Gaul's population, of which 90% was autochthonous;[43][44] instead, the key Latinizing class was the coopted local elite, who sent their children to Roman schools and administered lands for Rome. In the fifth century, at the time of the Western Roman collapse, the vast majority (non-elite and predominantly rural) of the population remained Gaulish speakers, and acquired Latin as their native speech only after the demise of the Empire, as both they and the new Frankish ruling elite adopted the prestige language of their urban literate elite.[45]

Bonnaud[46] maintains that Latinization occurred earlier in Provence and in major urban centers, while Gaulish persisted longest, possibly as late as the tenth century[47] with evidence for continued use according to Bonnaud continuing into the ninth century,[48] in Langres and the surrounding regions, the regions between Clermont, Argenton and Bordeaux, and in Armorica. Fleuriot,[49] Falc'hun,[50] and Gvozdanovic[51] likewise maintained a late survival in Armorica and language contact of some form with the ascendant Breton language; however, it has been noted that there is little uncontroversial evidence supporting a relatively late survival specifically in Brittany whereas there is uncontroversial evidence that supports the relatively late survival of Gaulish in the Swiss Alps and in regions in Central Gaul.[52] Drawing from these data, which include the mapping of substrate vocabulary as evidence, Kerkhof argues that we may "tentatively" posit a survival of Gaulish speaking communities "at least into the sixth century" in pockets of mountainous regions of the Central Massif, the Jura, and the Swiss Alps.[52]

Corpus

Summary of sources

According to Recueil des inscriptions gauloises, more than 760 Gaulish inscriptions have been found throughout France, with the notable exception of Aquitaine, and in northern Italy.[53] Inscriptions include short dedications, funerary monuments, proprietary statements, and expressions of human sentiments, but also some longer documents of a legal or magical-religious nature,[2] the three longest being the Larzac tablet, the Chamalières tablet and the Lezoux dish. The most famous Gaulish record is the Coligny calendar, a fragmented bronze tablet dating from the 2nd century CE and providing the names of Celtic months over a five-year span; it is a lunisolar calendar trying to synchronize the solar year and the lunar month by inserting a thirteenth month every two and a half years. There is also a longish (11 lines) inscribed tile from Châteaubleau that has been interpreted as a curse or alternatively as a sort of wedding proposal.[54]

Many inscriptions are only a few words (often names) in rote phrases, and many are fragmentary.[55][56] It is clear from the subject matter of the records that the language was in use at all levels of society.

Other sources contribute to knowledge of Gaulish: Greek and Latin authors mention Gaulish words,[20] personal and tribal names,[57] and toponyms. A short Gaulish-Latin vocabulary (about 20 entries headed De nominib[us] Gallicis) called "Endlicher's Glossary" is preserved in a 9th-century manuscript (Öst. Nationalbibliothek, MS 89 fol. 189v).[25]

French now has about 150 to 180 known words of Gaulish origin, most of which concern pastoral or daily activity.[58][59] If dialectal and derived words are included, the total is about 400 words. This is the highest number among the Romance languages.[60][61]

Inscriptions

Gaulish inscriptions are edited in the Recueil des Inscriptions Gauloises (R.I.G.), in four volumes: [date missing]

- Volume 1: Inscriptions in the Greek alphabet, edited by Michel Lejeune (items G-1 –G-281)[date missing]

- Volume 2.1: Inscriptions in the Etruscan alphabet (Lepontic, items E-1 – E-6), and inscriptions in the Latin alphabet in stone (items l. 1 – l. 16), edited by Michel Lejeune[date missing]

- Volume 2.2: inscriptions in the Latin alphabet on instruments (ceramic, lead, glass etc.), edited by Pierre-Yves Lambert (items l. 18 – l. 139)[date missing]

- Volume 3: The Coligny calendar (73 fragments) and that of Villards-d'Héria (8 fragments), edited by Paul-Marie Duval and Georges Pinault[date missing]

- Volume 4: inscriptions on Celtic coinage, edited by Jean-Baptiste Colbert de Beaulieu and Brigitte Fischer (338 items)[date missing]

The longest known Gaulish text is the Larzac tablet, found in 1983 in l'Hospitalet-du-Larzac, France. It is inscribed in Roman cursive on both sides of two small sheets of lead. Probably a curse tablet (defixio), it clearly mentions relationships between female names, for example aia duxtir adiegias [...] adiega matir aiias (Aia, daughter of Adiega... Adiega, mother of Aia) and seems to contain incantations regarding one Severa Tertionicna and a group of women (often thought to be a rival group of witches), but the exact meaning of the text remains unclear.[63][64]

The Coligny calendar was found in 1897 in Coligny, France, with a statue identified as Mars. The calendar contains Gaulish words but Roman numerals, permitting translations such as lat evidently meaning days, and mid month. Months of 30 days were marked matus, "lucky," months of 29 days anmatus, "unlucky," based on comparison with Middle Welsh mad and anfad, but the meaning could here also be merely descriptive, "complete" and "incomplete."[65]

The pottery at La Graufesenque[66] is the most important source for Gaulish numerals. Potters shared furnaces and kept tallies inscribed in Latin cursive on ceramic plates, referring to kiln loads numbered 1 to 10:

- 1st cintus, cintuxos (Welsh cynt "before," cyntaf "first," Breton kent "in front" kentañ "first," Cornish kynsa "first," Old Irish céta, Irish céad "first")

- 2nd allos, alos (Welsh ail, Breton eil, Old Irish aile "other," Irish eile)

- 3rd tri[tios] (Welsh trydydd, Breton trede, Old Irish treide)

- 4th petuar[ios] (Welsh pedwerydd, Breton pevare)

- 5th pinpetos (Welsh pumed, Breton pempet, Old Irish cóiced)

- 6th suexos (possibly mistaken for suextos, but see Rezé inscription below; Welsh chweched, Breton c'hwec'hved, Old Irish seissed)

- 7th sextametos (Welsh seithfed, Breton seizhved, Old Irish sechtmad)

- 8th oxtumeto[s] (Welsh wythfed, Breton eizhved, Old Irish ochtmad)

- 9th namet[os] (Welsh nawfed, Breton naved, Old Irish nómad)

- 10th decametos, decometos (CIb dekametam, Welsh degfed, Breton degvet, Old Irish dechmad)

The lead inscription from Rezé (dated to the 2nd century, at the mouth of the Loire, 450 kilometres (280 mi) northwest of La Graufesenque) is evidently an account or a calculation and contains quite different ordinals:[67]

- 3rd trilu

- 4th paetrute

- 5th pixte

- 6th suexxe, etc.

Other Gaulish numerals attested in Latin inscriptions include *petrudecametos "fourteenth" (rendered as petrudecameto, with Latinized dative-ablative singular ending) and *triconts "thirty" (rendered as tricontis, with a Latinized ablative plural ending; compare Irish tríocha). A Latinized phrase for a "ten-night festival of (Apollo) Grannus," decamnoctiacis Granni, is mentioned in a Latin inscription from Limoges. A similar formation is to be found in the Coligny calendar, in which mention is made of a trinox[...] Samoni "three-night (festival?) of (the month of) Samonios." As is to be expected, the ancient Gaulish language was more similar to Latin than modern Celtic languages are to modern Romance languages. The ordinal numerals in Latin are prīmus/prior, secundus/alter (the first form when more than two objects are counted, the second form only when two, alius, like alter means "the other," the former used when more than two and the latter when only two), tertius, quārtus, quīntus, sextus, septimus, octāvus, nōnus, and decimus.

An inscription in stone from Alise-Sainte-Reine (first century CE) reads:

- MARTIALIS DANNOTALI IEVRV VCVETE SOSIN CELICNON

- ETIC GOBEDBI DVGIIONTIIO VCVETIN IN ALISIIA

A number of short inscriptions are found on spindle whorls and are among the most recent finds in the Gaulish language. Spindle whorls were apparently given to girls by their suitors and bear such inscriptions as:

- moni gnatha gabi / buððutton imon (RIG l. 119) "my girl, take my penis(?)"[70] (or "little kiss"?)[71]

- geneta imi / daga uimpi (RIG l. 120) '"I am a young girl, good (and) pretty."

A gold ring found in Thiaucourt seems to express the wearers undying loyalty to her lover:

- Adiantunne, ni exuertinin appisetu "May (this ring) never see (me) turn away (from you), Adiantunnos!"[72][73]

Inscriptions found in Switzerland are rare. The most notable inscription found in Helvetic parts is the Bern zinc tablet, inscribed ΔΟΒΝΟΡΗΔΟ ΓΟΒΑΝΟ ΒΡΕΝΟΔΩΡ ΝΑΝΤΑΡΩΡ (Dobnorēdo gobano brenodōr nantarōr) and apparently dedicated to Gobannus, the Celtic god of metalwork. Furthermore, there is a statue of a seated goddess with a bear, Artio, found in Muri bei Bern, with a Latin inscription DEAE ARTIONI LIVINIA SABILLINA, suggesting a Gaulish Artiū "Bear (goddess)".

Some coins with Gaulish inscriptions in the Greek alphabet have also been found in Switzerland, e.g. RIG IV Nos. 92 (Lingones) and 267 (Leuci). A sword, dating to the La Tène period, was found in Port, near Biel/Bienne, with its blade inscribed with ΚΟΡΙϹΙΟϹ (Korisios), probably the name of the smith.

Phonology

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | o oː | |

| Open | a aː |

- vowels:

- short: a, e, i, o, u

- long: ā, ē, ī, (ō), ū

- diphthongs: ai, ei, oi, au, eu, ou

| Bilabial | Dental Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m | n | ||

| Stops | p b | t d | k ɡ | |

| Affricates | ts | |||

| Fricatives | s | x1 | ||

| Approximants | j | w | ||

| Liquids | r, l |

- [x] is an allophone of /k/ before /t/.

- occlusives:

- voiceless: p, t, k

- voiced: b, d, g

- resonants

- nasals: m, n

- liquids r, l

- sibilant: s

- affricate: ts

- semi-vowels: w, y

The diphthongs all transformed over the historical period. Ai and oi changed into long ī and eu merged with ou, both becoming long ō. Ei became long ē. In general, long diphthongs became short diphthongs and then long vowels. Long vowels shortened before nasals in coda.

Other transformations include unstressed i became e, ln became ll, a stop + s became ss, and a nasal + velar became ŋ + velar.

The lenis plosives seem to have been voiceless, unlike in Latin, which distinguished lenis occlusives with a voiced realization from fortis occlusives with a voiceless realization, which caused confusions like Glanum for Clanum, vergobretos for vercobreto, Britannia for Pritannia.[74]

Orthography

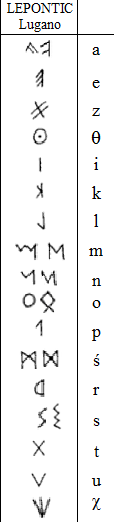

Lugano script

The alphabet of Lugano used in Cisalpine Gaul for Lepontic:

- AEIKLMNOPRSTΘVXZ

The alphabet of Lugano does not distinguish voicing in stops: P represents /b/ or /p/, T is for /d/ or /t/, K for /g/ or /k/. Z is probably for /ts/. U /u/ and V /w/ are distinguished in only one early inscription. Θ is probably for /t/ and X for /g/ (Lejeune 1971, Solinas 1985).

Greek script

The Eastern Greek alphabet used in southern Gallia Narbonensis.

| Letter | Pronunciation | Usage notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phoneme | IPA | ||

| Α | a | [a] | |

| Β | b | [b] | |

| Γ | g | [g] | |

| Δ | d | [d] | |

| Ε | e | [e] | |

| ē | [eː] | ||

| Ζ | z | [z] | |

| Η | e | [e] | |

| ē | [eː] | ||

| Θ | Never used alone | ||

| ΘΘ | ts | [t͡s] | |

| Ι | i | [i] | |

| ī | [iː] | ||

| ΕΙ | i | [i] | |

| ī | [iː] | ||

| Κ | k | [k] | |

| Λ | l | [l] | |

| Μ | m | [m] | |

| Ν | n | [n] | |

| Ξ | Earlier: xs | [xs] | Not attested. Existence is hinted by later use of Latin letters -XS- to denote /xs/ |

| Later: ks | [ks] | Used in parallel with -ΓϹ- | |

| ΓϹ | ks | [ks] | |

| Ο | o | [o] | |

| ō | [oː] | ||

| Π | p | [p] | |

| Ρ | r | [r] | |

| Ϲ | s | [s] | |

| Τ | t | [t] | |

| Υ | Never used alone | ||

| ΟΥ | u | [u] | Also used to denote the final element of the diphthongs:

|

| w | [w] | ||

| Χ | x | [x] | Used only in the consonant cluster -ΧΤ- (/xt/) |

| Ω | o | [o] | |

| ō | [oː] | ||

Latin script

Latin alphabet (monumental and cursive) in use in Roman Gaul:

- ABCDꟇEFGHIKLMNOPQRSTVXZ

- abcdꟈefghiklmnopqrstvxz

G and K are sometimes used interchangeably (especially after R). Ꟈ/ꟈ, ds and s may represent {/ts/ and/or /dz/. X, x is for [x] or /ks/. Q is only used rarely (Sequanni, Equos) and may represent an archaism (a retained *kw), borrowings from Latin, or, as in Latin, an alternate spelling of -cu- (for original /kuu/, /kou/, or /kom-u/).[78] Ꟈ is the letter tau gallicum, the Gaulish dental affricate. The letter ꟉꟉ/ꟊꟊ occurs in some inscriptions.[79]

Sound laws

- Gaulish changed the Proto-Celtic voiceless labiovelar *kʷ (from both PIE *kʷ and PIE *k'w) to p, a development also observed in the Brittonic languages (as well as Greek and some Italic languages like the Osco-Umbrian languages), while other Celtic languages retained the labiovelar. Thus, the Gaulish word for "son" was mapos,[80] contrasting with Primitive Irish

- maq(q)os (attested genitive case maq(q)i), which became mac (gen. mic) in modern Irish. In modern Welsh the word map, mab (or its contracted form ap, ab) is found in surnames. Similarly one Gaulish word for "horse" was epos (in Old Breton eb and modern Breton keneb "pregnant mare") while Old Irish has ech, the modern Irish language and Scottish Gaelic each, and Manx egh, all derived from proto-Indo-European

- h₁éḱwos.[81] The retention or innovation of this sound does not necessarily signify a close genetic relationship between the languages; Goidelic and Brittonic are, for example, both Insular Celtic languages and quite closely related.

- The Proto-Celtic voiced labiovelar *gʷ (from PIE *gʷʰ) became w: *gʷediūmi → uediiumi "I pray" (but Celtiberian Ku.e.z.o.n.to /gueðonto/ < *gʷʰedʰ-y-ont 'imploring, pleading', Old Irish guidim, Welsh gweddi "to pray").

- PIE *ds, *dz became /tˢ/, spelled ð: *neds-samo → neððamon (cf. Irish nesamh "nearest", Welsh nesaf "next", Modern Breton nes and nesañ "next").

- PIE *ew became eu or ou, and later ō: PIE *tewtéh₂ → *teutā/*toutā → tōtā "tribe" (cf. Irish túath, Welsh tud "people").

- PIE *ey became ei, ē and ī PIE *treyes → treis → trī (cf. Irish trí "three").

- Additionally, intervocalic /st/ became the affricate [tˢ] (alveolar stop + voiceless alveolar stop) and intervocalic /sr/ became [ðr] and /str/ became [θr]. Finally, labial and velar stops merged into the fricative [χ] when occurring before /t/ or /s/.

Morphology

There was some areal (and genetic, see Indo-European and the controversial Italo-Celtic hypothesis) similarity to Latin grammar, and the French historian Ferdinand Lot argued that it helped the rapid adoption of Vulgar Latin in Roman Gaul.[82]

Noun cases

Gaulish had seven cases: the nominative, vocative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental and the locative case. Greater epigraphical evidence attests common cases (nominative and accusative) and common stems (-o- and -a- stems) than for cases less frequently used in inscriptions or rarer -i-, -n- and -r- stems. The following table summarises the reconstructed endings for the words *toṷtā "tribe, people," *mapos "boy, son," *ṷātis "seer," *gutus "voice," and *brātīr "brother."[83][84]

| Case | Singular | Plural | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ā-stem | o-stem | i-stem | u-stem | r-stem | ā-stem | o-stem | i-stem | u-stem | r-stem | ||

| Nominative | *toṷtā | *mapos (n. *-on) | *ṷātis | *gutus | *brātīr | *toṷtās | *mapoi | *ṷātīs | *gutoṷes | *brāteres | |

| Vocative | *toṷtā | *mape | *ṷāti | *gutu | *brāter | *toṷtās | *mapoi | *ṷātīs | *gutoṷes | *brāteres | |

| Accusative | *toṷtan ~ *toṷtam > *toṷtim | *mapon ~ *mapom (n. *-on) | *ṷātin ~ *ṷātim | *gutun ~ *gutum | *brāterem | *toṷtās | *mapōs > *mapūs | *ṷātīs | *gutūs | *brāterās | |

| Genitive | toṷtās > *toṷtiās | *mapoiso > *mapi | *ṷātēis | *gutoṷs > *gutōs | *brātros | *toṷtanom | *mapon | *ṷātiom | *gutoṷom | *brātron | |

| Dative | *toṷtai > *toṷtī | *mapūi > *mapū | *ṷātei > *ṷāte | *gutoṷei > gutoṷ | *brātrei | *toṷtābo(s) | *mapobo(s) | *ṷātibo(s) | *gutuibo(s) | *brātrebo(s) | |

| Instrumental | *toṷtia > *toṷtī | *mapū | *ṷātī | *gutū | *brātri | *toṷtābi(s) | *mapuis > *mapūs | *ṷātibi(s) | *gutuibi(s) | *brātrebi(s) | |

| Locative | *toṷtī | *mapei > *mapē | *ṷātei | *gutoṷ | *brātri | *toṷtābo(s) | *mapois | *ṷātibo(s) | *gutubo(s) | *brātrebo(s) | |

In some cases, a historical evolution is attested; for example, the dative singular of a-stems is -āi in the oldest inscriptions, becoming first *-ăi and finally -ī as in Irish a-stem nouns with attenuated (slender) consonants: nom. lámh "hand, arm" (cf. Gaul. lāmā) and dat. láimh (< *lāmi; cf. Gaul. lāmāi > *lāmăi > lāmī). Further, the plural instrumental had begun to encroach on the dative plural (dative atrebo and matrebo vs. instrumental gobedbi and suiorebe), and in the modern Insular Languages, the instrumental form is known to have completely replaced the dative.

For o-stems, Gaulish also innovated the pronominal ending for the nominative plural -oi and genitive singular -ī in place of expected -ōs and -os still present in Celtiberian (-oś, -o). In a-stems, the inherited genitive singular -as is attested but was subsequently replaced by -ias as in Insular Celtic. The expected genitive plural -a-om appears innovated as -anom (vs. Celtiberian -aum).

There also appears to be a dialectal equivalence between -n and -m endings in accusative singular endings particularly, with Transalpine Gaulish favouring -n, and Cisalpine favouring -m. In genitive plurals the difference between -n and -m relies on the length of the preceding vowel, with longer vowels taking -m over -n (in the case of -anom this is a result of its innovation from -a-om).

Verbs

Gaulish verbs have present, future, perfect, and imperfect tenses; indicative, subjunctive, optative and imperative moods; and active and passive voices.[84][85] Verbs show a number of innovations as well. The Indo-European s-aorist became the Gaulish t-preterit, formed by merging an old third-person singular imperfect ending -t- to a third-person singular perfect ending -u or -e and subsequent affixation to all forms of the t-preterit tense. Similarly, the s-preterit is formed from the extension of -ss (originally from the third person singular) and the affixation of -it to the third-person singular (to distinguish it as such). Third-person plurals are also marked by addition of -s in the preterit.

Syntax

Word order

Most Gaulish sentences seem to consist of a subject–verb–object word order:

Subject Verb Indirect Object Direct Object martialis dannotali ieuru ucuete sosin celicnon Martialis, son of Dannotalos, dedicated this edifice to Ucuetis

Some, however, have patterns such as verb–subject–object (as in living Insular Celtic languages) or with the verb last. The latter can be seen as a survival from an earlier stage in the language, very much like the more archaic Celtiberian language.

Sentences with the verb first can be interpreted, however, as indicating a special purpose, such as an imperative, emphasis, contrast, and so on. Also, the verb may contain or be next to an enclitic pronoun or with "and," "but," etc. According to J. F. Eska, Gaulish was certainly not a verb-second language, as the following shows:

ratin briuatiom frontu tarbetisonios ie(i)uru NP.Acc.Sg. NP.Nom.Sg. V.3rd Sg. Frontus Tarbetisonios dedicated the board of the bridge.

Whenever there is a pronoun object element, it is next to the verb, as per Vendryes' Restriction. The general Celtic grammar shows Wackernagel's rule, so putting the verb at the beginning of the clause or sentence. As in Old Irish[86] and traditional literary Welsh,[87] the verb can be preceded by a particle with no real meaning by itself but originally used to make the utterance easier.

sioxt-i albanos panna(s) extra tuꟈ(on) CCC V-Pro.Neut. NP.Nom.Sg. NP.Fem.Acc.Pl. PP Num. Albanos added them, vessels beyond the allotment (in the amount of) 300.

to-me-declai obalda natina Conn.-Pro.1st.Sg.Acc.-V.3rd.Sg. NP.Nom.Sg. Appositive Obalda, (their) dear daughter, set me up.

According to Eska's model, Vendryes' Restriction is believed to have played a large role in the development of Insular Celtic verb-subject-object word order. Other authorities such as John T. Koch, dispute that interpretation.[citation needed]

Considering that Gaulish is not a verb-final language, it is not surprising to find other "head-initial" features:

- Genitives follow their head nouns:

atom deuogdonion The border of gods and men.

- The unmarked position for adjectives is after their head nouns:

toutious namausatis citizen of Nîmes

- Prepositional phrases have the preposition, naturally, first:

in alixie in Alesia

- Passive clauses:

uatiounui so nemetos commu escengilu To Vatiounos this shrine (was dedicated) by Commos Escengilos

Subordination

Subordinate clauses follow the main clause and have an uninflected element (jo) to show the subordinate clause. This is attached to the first verb of the subordinate clause.

gobedbi dugijonti-jo ucuetin in alisija NP.Dat/Inst.Pl. V.3rd.Pl.- Pcl. NP.Acc.Sg. PP to the smiths who serve Ucuetis in Alisia

Jo is also used in relative clauses and to construct the equivalent of THAT-clauses

scrisu-mi-jo uelor V.1st.Sg.-Pro.1st Sg.-Pcl. V.1st Sg. I wish that I spit

This element is found residually in the Insular Celtic languages and appears as an independent inflected relative pronoun in Celtiberian, thus:

- Welsh

- modern sydd "which is" ← Middle Welsh yssyd ← *esti-jo

- vs. Welsh ys "is" ← *esti

- Irish

- Old Irish relative cartae "they love" ← *caront-jo

- Celtiberian

Clitics

Gaulish had object pronouns that affixed inside a word:

to- so -ko -te Conn.- Pro.3rd Sg.Acc - PerfVZ - V.3rd Sg he gave it

Disjunctive pronouns also occur as clitics: mi, tu, id. They act like the emphasizing particles known as notae augentes in the Insular Celtic languages.

dessu- mii -iis V.1st.Sg. Emph.-Pcl.1st Sg.Nom. Pro.3rd Pl.Acc. I prepare them

buet- id V.3rd Sg.Pres.Subjunc.- Emph.Pcl.3rd Sg.Nom.Neut. it should be

Clitic doubling is also found (along with left dislocation), when a noun antecedent referring to an inanimate object is nonetheless grammatically animate. (There is a similar construction in Old Irish.)

Modern usage

In an interview, Swiss folk metal band Eluveitie said that some of their songs are written in a reconstructed form of Gaulish. The band asks scientists for help in writing songs in the language.[88] The name of the band comes from graffiti on a vessel from Mantua (c. 300 BC).[89] The inscription in Etruscan letters reads eluveitie, which has been interpreted as the Etruscan form of the Celtic (h)elvetios ("the Helvetian"),[90] presumably referring to a man of Helvetian descent living in Mantua.

See also

References

Citations

Bibliography

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (in French). Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2012), Noms de lieux celtiques de l'Europe Ancienne. -500 +500, Arles: Errance

- Eska, Joseph F. (2004), "Celtic Languages", in Woodard, Roger D. (ed.), Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge UP, pp. 857–880

- Eska, Joseph F. (2008), "Continental Celtic", in Woodard, Roger D. (ed.), The Ancient Languages of Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge UP, pp. 165–188

- Eska, Joseph F (1998), "The linguistic position of Lepontic", Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 24 (2): 2–11, doi:10.3765/bls.v24i2.1254

- Eska, Joseph F. (2010), "The emergence of the Celtic languages", in Ball, Martin J.; Müller, Nicole (eds.), The Celtic Languages (2nd ed.), London: Routledge, pp. 22–27

- Eska, Joseph F. (2012), "Lepontic", in Koch, John T.; Minard, Antoine (eds.), The Celts: History, Life, and Culture, Santa Barbara: ABC Clio, p. 534

- Eska, Joseph F.; Evans, D. Ellis (2010), "Continental Celtic", in Ball, Martin J.; Müller, Nicole (eds.), The Celtic Languages (2nd ed.), London: Routledge, pp. 28–54

- Evans, David E. (1967). Gaulish Personal Names: A Study of Some Continental Celtic Formations. Clarendon Press.

- Dottin, Georges (1920), La langue gauloise: grammaire, textes et glossaire, Paris: C. Klincksieck

- Forster, Peter; Toth, Alfred (2003), "Toward a phylogenetic chronology of ancient Gaulish, Celtic, and Indo-European", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 100 (15): 9079–9084, Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.9079F, doi:10.1073/pnas.1331158100, PMC 166441, PMID 12837934

- Koch, John T. (2005), Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- Lacroix, Jacques (2020), Les irréductibles mots gaulois dans la langue française, Lemme Edit, ISBN 978-2-917575-89-5.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (1994). La langue gauloise: description linguistique, commentaire d'inscriptions choisies (in French). Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-089-2.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (1997). "L'épigraphie gallo-grecque" [Gallo-Greek Epigraphy]. In Christol, Michel; Masson, Olivier (eds.). Actes du Xe congrès international d'épigraphie grecque et latine, Nîmes, 4–9 octobre 1992 [Proceedings of the Xth International Congress of Greek and Latin Epigraphy, Nîmes, 4–9 October 1992]. Paris, France: Université Panthéon-Sorbonne. pp. 35–50. ISBN 978-2-859-44281-1.

- Lejeune, Michel (1971), Lepontica, Paris: Belles Lettres

- Meid, Wolfgang (1994), Gaulish Inscriptions, Archaeolingua

- Recueil des inscriptions gauloises (XLVe supplément à «GALLIA»). ed. Paul-Marie Duval et al. 4 vols. Paris: CNRS, 1985–2002. ISBN 2-271-05844-9

- Russell, Paul (1995), An Introduction to the Celtic Languages, London: Longman

- Savignac, Jean-Paul (2004), Dictionnaire français-gaulois, Paris: Éditions de la Différence

- Savignac, Jean-Paul (1994), Les Gaulois, leurs écrits retrouvés: "Merde à César", Paris: Éditions de la Différence

- Sims-Williams, Patrick (2007), "Common Celtic, Gallo-Brittonic and Insular Celtic", in Lambert, Pierre-Yves; Pinault, Jean (eds.), Gaulois et celtique continental, Genève: Librairie Droz, pp. 309–354

- Solinas, Patrizia (1995), "Il celtico in Italia", Studi Etruschi, 60: 311–408

- Stifter, David (2012), Old Celtic Languages (lecture notes), University of Kopenhagen

- Vath, Bernd; Ziegler, Sabine (2017). "The documentation of Celtic". In Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (eds.). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. Vol. 2. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-054243-1.

- Watkins, Calvert (1999), "A Celtic miscellany", in K. Jones-Blei; et al. (eds.), Proceedings of the Tenth Annual UCLA Indo-European Conference, Los Angeles 1998, Washington: Institute for the Study of Man, pp. 3–25

Further reading

- Beck, Noémie. "Celtic Divine Names Related to Gaulish and British Population Groups." In: Théonymie Celtique, Cultes, Interpretatio – Keltische Theonymie, Kulte, Interpretatio. Edited by Hofeneder, Andreas and De Bernardo Stempel, Patrizia, by Hainzmann, Manfred and Mathieu, Nicolas. Wein: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2013. 51–72. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv8mdn28.7.

- Hamp, Eric P. "Gaulish ordinals and their history". In: Études Celtiques, vol. 38, 2012. pp. 131–135. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.2012.2349]; [www.persee.fr/doc/ecelt_0373-1928_2012_num_38_1_2349]

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves. "Le Statut Du Théonyme Gaulois." In Théonymie Celtique, Cultes, Interpretatio – Keltische Theonymie, Kulte, Interpretatio, edited by Hofeneder Andreas and De Bernardo Stempel Patrizia, by Hainzmann Manfred and Mathieu Nicolas, 113-24. Wein: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2013. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv8mdn28.11.

- Kennedy, James (1855). "On the Ancient Languages of France and Spain". Transactions of the Philological Society. 2 (11): 155–184. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1855.tb00784.x.

- Mullen, Alex; Darasse, Coline Ruiz. "Gaulish". In: Palaeohispanica: revista sobre lenguas y culturas de la Hispania antigua n. 20 (2020): pp. 749–783. ISSN 1578-5386 DOI: 10.36707/palaeohispanica.v0i20.383

- Witczak, Krzysztof Tomasz. "Gaulish SUIOREBE ‘with two sisters’", Lingua Posnaniensis 57, 2: 59–62, doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/linpo-2015-0011

External links

- L.A. Curchin, "Gaulish language"

- (in French) Langues et écriture en Gaule Romaine by Hélène Chew of the Musée des Antiquités Nationales

- two sample inscriptions on TITUS