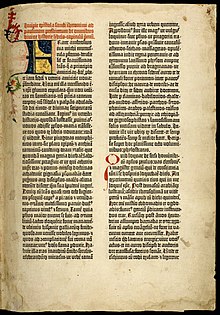

The Gutenberg Bible, also known as the 42-line Bible, the Mazarin Bible or the B42, was the earliest major book printed in Europe using mass-produced metal movable type. It marked the start of the "Gutenberg Revolution" and the age of printed books in the West. The book is valued and revered for its high aesthetic and artistic qualities[1] and its historical significance.

The Gutenberg Bible is an edition of the Latin Vulgate printed in the 1450s by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz, in present-day Germany. Forty-nine copies (or substantial portions of copies) have survived. They are thought to be among the world's most valuable books, although no complete copy has been sold since 1978.[2][3] In March 1455, the future Pope Pius II wrote that he had seen pages from the Gutenberg Bible displayed in Frankfurt to promote the edition, and that either 158 or 180 copies had been printed.

The 36-line Bible, said to be the second printed Bible, is also sometimes referred to as a Gutenberg Bible, but may be the work of another printer.

Text

The Gutenberg Bible, an edition of the Vulgate, contains the Latin version of the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament. It is mainly the work of St Jerome who began his work on the translation in AD 380, with emendations from the Parisian Bible tradition, and further divergences.[4]

Printing history

While it is unlikely that any of Gutenberg's early publications would bear his name, the initial expense of press equipment and materials and of the work to be done before the Bible was ready for sale suggests that he may have started with more lucrative texts, including several religious documents, a German poem, and some editions of Aelius Donatus's Ars Minor, a popular Latin grammar school book.[5][6][7]

Preparation of the Bible probably began soon after 1450, and the first finished copies were available in 1454 or 1455.[8] It is not known exactly how long the Bible took to print. The first precisely datable printing is Gutenberg's 31-line Indulgence which certainly existed by 22 October 1454.[9]

Gutenberg made three significant changes during the printing process.[10]

Some time later, after more sheets had been printed, the number of lines per page was increased from 40 to 42, presumably to save paper. Therefore, pages 1 to 9 and pages 256 to 265, presumably the first ones printed, have 40 lines each. Page 10 has 41, and from there on the 42 lines appear. The increase in line number was achieved by decreasing the interline spacing, rather than increasing the printed area of the page. Finally, the print run was increased, necessitating resetting those pages which had already been printed. The new sheets were all reset to 42 lines per page. Consequently, there are two distinct settings in folios 1–32 and 129–158 of volume I and folios 1–16 and 162 of volume II.[10][11]

The most reliable information about the Bible's date comes from a letter. In March 1455, the future Pope Pius II wrote that he had seen pages from the Gutenberg Bible, being displayed to promote the edition, in Frankfurt.[12] It is not known how many copies were printed, with the 1455 letter citing sources for both 158 and 180 copies. Scholars today think that examination of surviving copies suggests that somewhere between 160 and 185 copies were printed, with about three-quarters on paper and the others on vellum.[13][14]

The production process: Das Werk der Bücher

In a legal paper, written after completion of the Bible, Johannes Gutenberg refers to the process as Das Werk der Bücher ("the work of the books"). He had introduced the printing press to Europe and created the technology to make printing with movable types finally efficient enough to facilitate the mass production of entire books.[15]

Many book-lovers have commented on the high standards achieved in the production of the Gutenberg Bible, some describing it as one of the most beautiful books ever printed. The quality of both the ink and other materials and the printing itself have been noted.[1]

Pages

The paper size is 'double folio', with two pages printed on each side (four pages per sheet). After printing the paper was folded once to the size of a single page. Typically, five of these folded sheets (ten leaves, or twenty printed pages) were combined to a single physical section, called a quinternion, that could then be bound into a book. Some sections, however, had as few as four leaves or as many as twelve leaves.[16]

The 42-line Bible was printed on the size of paper known as 'Royal'.[17] A full sheet of Royal paper measures 42 cm × 60 cm (17 in × 24 in) and a single untrimmed folio leaf measures 42 cm × 30 cm (17 in × 12 in).[18] There have been attempts to claim that the book was printed on larger paper measuring 44.5 cm × 30.7 cm (17.5 in × 12.1 in),[19] but this assertion is contradicted by the dimensions of existing copies. For example, the leaves of the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, measure 40 cm × 28.6 cm (15.7 in × 11.3 in).[20] This is typical of other folio Bibles printed on Royal paper in the fifteenth century.[21] Most fifteenth-century printing papers have a width-to-height ratio of 1:1.4 (e.g. 30:42 cm) which, mathematically, is a ratio of 1 to the square root of 2 or, simply,

Ink

In Gutenberg's time, inks used by scribes to produce manuscripts were water-based. Gutenberg developed an oil-based ink that would better adhere to his metal type. His ink was primarily carbon, but also had a high metallic content, with copper, lead, and titanium predominating.[25] Head of collections at the British Library, Kristian Jensen, described it thus: "if you look [at the pages of The Gutenberg Bible] closely you will see this is a very shiny surface. When you write you use a water-based ink, you put your pen into it and it runs off. Now if you print that's exactly what you don't want. One of Gutenberg's inventions was an ink which wasn't ink, it's a varnish. So what we call printer's ink is actually a varnish, and that means it sticks to its surface."[26][27]

Type

Each unique character requires a piece of master type in order to be replicated. Given that each letter has uppercase and lowercase forms, and the number of various punctuation marks and ligatures (e.g., "fi" for the letter sequence "fi", commonly used in writing), the Gutenberg Bible needed a set of 290 master characters. It seems probable that six pages, containing 15,600 characters altogether, would be set at any one moment.[5]

Type style

The Gutenberg Bible is printed in the blackletter type styles that would become known as Textualis (Textura) and Schwabacher. The name Textura refers to the texture of the printed page: straight vertical strokes combined with horizontal lines, giving the impression of a woven structure. Gutenberg already used the technique of justification, that is, creating a vertical, not indented, alignment at the left and right-hand sides of the column. To do this, he used various methods, including using characters of narrower widths, adding extra spaces around punctuation, and varying the widths of spaces around words.[28][29]

Rubrication, illumination and binding

Initially the rubrics—the headings before each book of the Bible—were printed, but this practice was quickly abandoned at an unknown date, and gaps were left for rubrication to be added by hand. A guide of the text to be added to each page, printed for use by rubricators, survives.[30]

The spacious margin allowed illuminated decoration to be added by hand. The amount of decoration presumably depended on how much each buyer could or would pay. Some copies were never decorated.[31] The place of decoration can be known or inferred for about 30 of the surviving copies. It is possible that 13 of these copies received their decoration in Mainz, but others were worked on as far away as London.[32] The vellum Bibles were more expensive, and perhaps for this reason tend to be more highly decorated, although the vellum copy in the British Library is completely undecorated.[33]

There has been speculation that the "Master of the Playing Cards", an unidentified engraver who has been called "the first personality in the history of engraving,"[34] was partly responsible for the illumination of the copy held by the Princeton University library. However, all that can be said for certain is that the same model book was used for some of the illustrations in this copy and for some of the Master's illustrated playing cards.[35]

Although many Gutenberg Bibles have been rebound over the years, nine copies retain fifteenth-century bindings. Most of these copies were bound in either Mainz or Erfurt.[32] Most copies were divided into two volumes, the first volume ending with The Book of Psalms. Copies on vellum were heavier and for this reason were sometimes bound in three or four volumes.[1]

Early owners

The Bible seems to have sold out immediately, with some initial purchases as far away as England and possibly Sweden and Hungary.[1][36] At least some copies are known to have sold for 30 florins (equivalent to about 100 grams or 3.5 ounces of gold), which was about three years' wages for a clerk.[37][38] Although this made them significantly cheaper than manuscript Bibles, most students, priests or other people of moderate income would not have been able to afford them. It is assumed that most were sold to monasteries, universities and particularly wealthy individuals.[30] At present only one copy is known to have been privately owned in the fifteenth century. Some are known to have been used for communal readings in monastery refectories; others may have been for display rather than use, and a few were certainly used for study.[1] Kristian Jensen suggests that many copies were bought by wealthy and pious laymen for donation to religious institutions.[33]

Influence on later Bibles

The Gutenberg Bible had a profound effect on the history of the printed book. Textually, it also had an influence on future editions of the Bible. It provided the model for several later editions, including the 36 Line Bible, Mentelin's Latin Bible, and the first and third Eggestein Bibles. The third Eggestein Bible was set from the copy of the Gutenberg Bible now in Cambridge University Library. The Gutenberg Bible also had an influence on the Clementine edition of the Vulgate commissioned by the Papacy in the late sixteenth century.[39][40]

Forgeries

Joseph Martini, a New York book dealer, found that the Gutenberg Bible held by the library of the General Theological Seminary in New York had a forged leaf, carrying part of Chapter 14, all of Chapter 15, and part of Chapter 16 of the Book of Ezekiel. It was impossible to tell when the leaf had been inserted into the volume. It was replaced in the fall of 1953, when a patron donated the corresponding leaf from a defective Gutenberg second volume which was being broken up and sold in parts.[41] This made it "the first imperfect Gutenberg Bible ever restored to completeness."[41] In 1978, this copy was sold for US$2.2 million to the Württembergische Landesbibliothek in Stuttgart, Germany.[42]

Surviving copies

As of 2009[update], 49 Gutenberg Bibles are known to exist, but of these only 21 are complete. Others have pages or even whole volumes missing. In addition, there are a substantial number of fragments, some as small as individual leaves, which are likely to represent about another 16 copies. Many of these fragments have survived because they were used as part of the binding of later books.[36]

Substantially complete copies

List of substantially complete copies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Recent history

Today, few copies remain in religious institutions, with most now owned by university libraries and other major scholarly institutions. After centuries in which all copies seem to have remained in Europe, the first Gutenberg Bible reached North America in 1847. It is now in the New York Public Library.[94] In the last hundred years, several long-lost copies have come to light, considerably improving the understanding of how the Bible was produced and distributed.[36]

In 1921 a New York rare book dealer, Gabriel Wells, bought a damaged paper copy, dismantled the book and sold sections and individual leaves to book collectors and libraries. The leaves were sold in a portfolio case with an essay written by A. Edward Newton, and were referred to as "Noble Fragments".[95][96] In 1953 Charles Scribner's Sons, also book dealers in New York, dismembered a paper copy of volume II. The largest portion of this, the New Testament, is now owned by Indiana University. The matching first volume of this copy was subsequently discovered in Mons, Belgium.[13]

The only copy held outside Europe and North America is the first volume of a Gutenberg Bible (Hubay 45) at Keio University in Tokyo. The Humanities Media Interface Project (HUMI) at Keio University is known for its high-quality digital images of Gutenberg Bibles and other rare books.[68] Under the direction of Professor Toshiyuki Takamiya, the HUMI team has made digital reproductions of 11 sets of the bible in nine institutions, including both full-text facsimiles held in the collection of the British Library.[97]

The last sale of a complete Gutenberg Bible took place in 1978, which sold for $2.4 million. This copy is now in Austin, Texas.[94] The price of a complete copy today is estimated at $25−35 million.[2][3]

A two-volume paper edition of the Gutenberg Bible was stolen from Moscow State University in 2009 and subsequently recovered in an FSB sting operation in 2013.[98]

Possession of a Gutenberg Bible by a library has been equated to keeping a "trophy book".[99]

See also

General bibliography

- Niels Henry Sonne. America's Oldest Episcopal Seminary Library and the Needs It Serves. New York?: General Theological Seminary, 1953.

- St. Mark's Library (General Theological Seminary). The Gutenberg Bible of the General Theological Seminary. New York: St. Mark's Library, the General Theological Seminary, 1963.

- The Gutenberg Bible of 1454, Göttingen Library, Facsimile Edition, 2 vols + booklet, ed. Stephan Füssel, 1400 pp. Taschen: Cologne. In Latin

References

External links

- Gutenberg Digital Public access to digitised copy of the Gutenberg Bible held by the Göttingen State and University Library in Germany

- Morgan Gutenberg Bible Online Digitised copy of the Gutenberg Bible at the Morgan Library & Museum in the United States

- Treasures in Full: Gutenberg Bible Archived 10 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Information about Gutenberg and the Bible as well as online images of the British Library's two copies

- Gutenberg Bible Census Details of surviving copies, including some notes on provenance

- The Munich copy of the Gutenberg Bible on bavarikon

- Tabula rubricarum (in German) Image of rubricators' instructions from the Munich copy

- 1462 The Gutenberg Bible Latin Vulgate – via archive.org.

- The Gutenberg Bible at the Beinecke Archived 2020-07-27 at the Wayback Machine Podcast from the Beinecke Library, Yale University

- The Gutenberg Leaf Image and information about a single "Noble Fragment" held by the McCune Collection in Vallejo, California

- History in the Headlines: 7 Things You May Not Know About the Gutenberg Bible History.com, February 23, 2015