Hyraxes (from Ancient Greek ὕραξ (húrax) 'shrewmouse'), also called dassies,[1][2] are small, thickset, herbivorous mammals in the order Hyracoidea. Hyraxes are well-furred, rotund animals with short tails.[3] Modern hyraxes are typically between 30 and 70 cm (12 and 28 in) long and weigh between 2 and 5 kg (4 and 11 lb). They are superficially similar to pikas and marmots, but are more closely related to elephants and sea cows.

| Hyraxes Temporal range: Eocene–recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Rock hyrax (Procavia capensis) Erongo, Namibia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Superorder: | Afrotheria |

| Clade: | Paenungulatomorpha |

| Grandorder: | Paenungulata |

| Order: | Hyracoidea Huxley, 1869 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

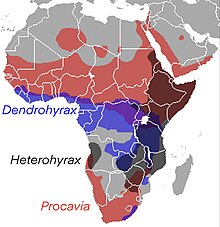

| The range map of Procaviidae, the only living family within Hyracoidea | |

Hyraxes have a life span from 9 to 14 years. Six extant species are recognised: the rock hyrax (Procavia capensis) and the yellow-spotted rock hyrax (Heterohyrax brucei), which both live on rock outcrops, including cliffs in Ethiopia[4] and isolated granite outcrops called koppies in southern Africa;[5] the western tree hyrax (Dendrohyrax dorsalis), southern tree hyrax (D. arboreus), eastern tree hyrax (D. validus)[6] and Benin tree hyrax (D. interfluvialis). Their distribution is limited to Africa, except for P. capensis, which is also found in the Middle East.

Hyraxes were a much more diverse group in the past encompassing species considerably larger than modern hyraxes. The largest known extinct hyrax, Titanohyrax ultimus has been estimated to weigh 600–1,300 kilograms (1,300–2,900 lb), comparable to a rhinoceros.[7]

Characteristics

Hyraxes retain or have redeveloped a number of primitive mammalian characteristics; in particular, they have poorly developed internal temperature regulation,[8] for which they compensate by behavioural thermoregulation, such as huddling together and basking in the sun.

Unlike most other browsing and grazing animals, they do not use the incisors at the front of the jaw for slicing off leaves and grass; rather, they use the molar teeth at the side of the jaw. The two upper incisors are large and tusk-like, and grow continuously through life, similar to those of rodents. The four lower incisors are deeply grooved "comb teeth". A diastema occurs between the incisors and the cheek teeth. The dental formula for hyraxes is 1.0.4.32.0.4.3.

Although not ruminants, hyraxes have complex, multichambered stomachs that allow symbiotic bacteria to break down tough plant materials, but their overall ability to digest fibre is lower than that of the ungulates.[9] Their mandibular motions are similar to chewing cud,[10] but the hyrax is physically incapable of regurgitation[11][12] as in the even-toed ungulates and some of the macropods. This behaviour is referred to in a passage in the Bible which describes hyraxes as "chewing the cud".[13] This chewing behaviour may be a form of agonistic behaviour when the animal feels threatened.[14]

The hyrax does not construct dens, as most rodents and rodent-like mammals do, but over the course of its lifetime rather seeks shelter in existing holes of great variety in size and configuration.[15]

Hyraxes inhabit rocky terrain across sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. Their feet have rubbery pads with numerous sweat glands, which may help the animal maintain its grip when quickly moving up steep, rocky surfaces. Hyraxes have stumpy toes with hoof-like nails; four toes are on each front foot and three are on each back foot.[16] They also have efficient kidneys, retaining water so that they can better survive in arid environments.

Female hyraxes give birth to up to four young after a gestation period of 7–8 months, depending on the species. The young are weaned at 1–5 months of age, and reach sexual maturity at 16–17 months.

Hyraxes live in small family groups, with a single male that aggressively defends the territory from rivals. Where living space is abundant, the male may have sole access to multiple groups of females, each with its own range. The remaining males live solitary lives, often on the periphery of areas controlled by larger males, and mate only with younger females.[17]

Hyraxes have highly charged myoglobin, which has been inferred to reflect an aquatic ancestry.[18]

Similarities with Proboscidea and Sirenia

Hyraxes share several unusual characteristics with mammalian orders Proboscidea (elephants and their extinct relatives) and Sirenia (manatees and dugongs), which have resulted in their all being placed in the taxon Paenungulata. Male hyraxes lack a scrotum and their testicles remain tucked up in their abdominal cavity next to the kidneys,[19][20] as do those of elephants, manatees, and dugongs.[21] Female hyraxes have a pair of teats near their armpits (axilla), as well as four teats in their groin (inguinal area); elephants have a pair of teats near their axillae, and dugongs and manatees have a pair of teats, one located close to each of the front flippers.[22][23] The tusks of hyraxes develop from the incisor teeth as do the tusks of elephants; most mammalian tusks develop from the canines. Hyraxes, like elephants, have flattened nails on the tips of their digits, rather than the curved, elongated claws usually seen on mammals.[24]

Evolution

All modern hyraxes are members of the family Procaviidae (the only living family within Hyracoidea) and are found only in Africa and the Middle East. In the past, however, hyraxes were more diverse and widespread. The order first appears in the fossil record at a site in the Middle East in the form of Dimaitherium, 37 million years ago.[25] For many millions of years, hyraxes, proboscideans, and other afrotherian mammals were the primary terrestrial herbivores in Africa, just as odd-toed ungulates were in North America.

Through the middle to late Eocene, many different species existed.[26] The smallest of these were the size of a mouse but others were much larger than any extant relatives. Titanohyrax could reach 600 kg (1,300 lb) or even as much as over 1,300 kg (2,900 lb).[27] Megalohyrax from the upper Eocene-lower Oligocene was as huge as a tapir.[28][29] During the Miocene, however, competition from the newly developed bovids, which were very efficient grazers and browsers, displaced the hyraxes into marginal niches. Nevertheless, the order remained widespread and diverse as late as the end of the Pliocene (about two million years ago) with representatives throughout most of Africa, Europe, and Asia.

The descendants of the giant "hyracoids" (common ancestors to the hyraxes, elephants, and sirenians) evolved in different ways. Some became smaller, and evolved to become the modern hyrax family. Others appear to have taken to the water (perhaps like the modern capybara), ultimately giving rise to the elephant family and perhaps also the sirenians. DNA evidence supports this hypothesis, and the small modern hyraxes share numerous features with elephants, such as toenails, excellent hearing, sensitive pads on their feet, small tusks, good memory, higher brain functions compared with other similar mammals, and the shape of some of their bones.[30]

Hyraxes are sometimes described as being the closest living relative of the elephant,[31] although whether this is so is disputed. Recent morphological- and molecular-based classifications reveal the sirenians to be the closest living relatives of elephants. While hyraxes are closely related, they form a taxonomic outgroup to the assemblage of elephants, sirenians, and the extinct orders Embrithopoda and Desmostylia.[32]

The extinct meridiungulate family Archaeohyracidae, consisting of seven genera of notoungulate mammals known from the Paleocene through the Oligocene of South America,[33] is a group unrelated to the true hyraxes.

List of genera

| Phylogeny of early hyracoids | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| A phylogeny of hyracoids known from the early Eocene through the middle Oligocene epoch.[34] |

- †Dimaitherium

- †Helioseus?

- †Microhyrax

- †Seggeurius

- †Geniohyidae

- †Brachyhyrax

- †Bunohyrax

- †Geniohyus

- †Namahyrax

- †Pachyhyrax

- †"Saghatheriidae" (Polyphyletic)

- †Megalohyrax

- †Regubahyrax

- †Rukwalorax

- †Saghatherium

- †Selenohyrax

- †Thyrohyrax

- †Titanohyracidae

- †Afrohyrax

- †Antilohyrax

- †Rupestrohyrax

- †Titanohyrax

- †Pliohyracidae

- †Hengduanshanhyrax

- †Kvabebihyrax

- †Meroehyrax

- †Parapliohyrax

- †Pliohyrax

- †Postschizotherium

- †Prohyrax

- Procaviidae

- Dendrohyrax (Tree hyrax)

- †Gigantohyrax

- Heterohyrax (Bush hyrax)

- Procavia (Rock hyrax)

Extant species

In the 2000s, taxonomists reduced the number of recognized species of hyraxes. In 1995, they recognized 11 species or more, but as of 2013, only four were recognized, with the others all considered as subspecies of one of the recognized four. Over 50 subspecies and species are described, many of which are considered highly endangered.[37] The most recently identified species is Dendrohyrax interfluvialis, which is a tree hyrax living between the Volta and Niger rivers but makes a unique barking call that is distinct from the shrieking vocalizations of hyraxes inhabiting other regions of the African forest zone.[38]

The following cladogram shows the relationship between the extant genera:[39]

| Hyracoidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (order) |

Human interactions

Local and indigenous names

Biblical references

References are made to hyraxes in the Hebrew Bible (Leviticus 11:5; Deuteronomy 14:7; Psalm 104:18; Proverbs 30:26). In Leviticus they are described as lacking a split hoof and therefore not being kosher. It also describes the hyrax as chewing its cud, reflecting its observable ruminant-like mandible motions; the Hebrew phrase in question (מַעֲלֵה גֵרָה) means "bringing up cud". Some of the modern translations refer to them as rock hyraxes.[43][44]

... hyraxes are creatures of little power, yet they make their home in the crags; ...

The words "rabbit", "hare", "coney", or "daman" appear as terms for the hyrax in some English translations of the Bible.[45][46] Early English translators had no knowledge of the hyrax, so no name for them, though "badger" or "rock-badger" has also been used more recently in new translations, especially in "common language" translations such as the Common English Bible (2011).[47]

"Spain"

One of the proposed etymologies for "Spain" is that it may be a derivation of the Phoenician I-Shpania, meaning "island of hyraxes", "land of hyraxes", but the Phoenecian-speaking Carthaginians are believed to have used this name to refer to rabbits, animals with which they were unfamiliar.[48] Roman coins struck in the region from the reign of Hadrian show a female figure with a rabbit at her feet,[49] and Strabo called it the "land of the rabbits".[50]

The Phoenician shpania is cognate to the modern Hebrew shafan.[51]

See also

References

External links

Data related to Procaviidae at Wikispecies

Data related to Procaviidae at Wikispecies Media related to Hyracoidea at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hyracoidea at Wikimedia Commons