An incunable or incunabulum (plural incunables or incunabula, respectively) is a book, pamphlet, or broadside that was printed in the earliest stages of printing in Europe, up to the year 1500. Incunabula were produced before the printing press became widespread on the continent and are distinct from manuscripts, which are documents written by hand. Some authorities on the history of printing include block books from the same time period as incunabula, whereas others limit the term to works printed using movable type.

As of 2021,[update] there are about 30,000 distinct incunable editions known.[1] The probable number of surviving individual copies is much higher, estimated at 125,000 in Germany alone.[2] Through statistical analysis, it is estimated that the number of lost editions is at least 20,000.[3] Around 550,000 copies of around 27,500 different works have been preserved worldwide.[4]

Terminology

Incunable is the anglicised form of incunabulum,[5] reconstructed singular of Latin incunabula,[6] which meant "swaddling clothes", or "cradle",[7] which could metaphorically refer to "the earliest stages or first traces in the development".[8] A former term for incunable is fifteener, meaning "fifteenth-century edition".[9]

The term incunabula was first used in the context of printing by the Dutch physician and humanist Hadrianus Junius (Adriaen de Jonghe, 1511–1575), in a passage in his work Batavia (written in 1569; published posthumously in 1588). He referred to a period "inter prima artis [typographicae] incunabula" ("in the first infancy of the typographic art").[10][11] The term has sometimes been incorrectly attributed to Bernhard von Mallinckrodt (1591–1664), in his Latin pamphlet De ortu ac progressu artis typographicae ("On the rise and progress of the typographic art"; 1640), but he was quoting Junius.[12][13]

The term incunabula came to denote printed books themselves in the late 17th century.[14] It is not found in English before the mid-19th century.[8]

Junius set an end-date of 1500 to his era of incunabula, which remains the convention in modern bibliographical scholarship.[10][11] This convenient but arbitrary end-date for identifying a printed book as an incunable does not reflect changes in the printing process, and many books printed for some years after 1500 are visually indistinguishable from incunables. The term "post-incunable" is now used to refer to books printed after 1500 up to 1520 or 1540, without general agreement. From around this period the dating of any edition becomes easier, as the practice of printing the place and year of publication using a colophon or on the title page became more widespread.[citation needed]

Types

There are two types of printed incunabula: the block book, printed from a single carved or sculpted wooden block for each page (the same process as the woodcut in art, called xylographic); and the typographic book, made by individual cast-metal movable type pieces on a printing press. Many authors reserve the term "incunabula" for the latter.[15]

The spread of printing to cities both in the North and in Italy ensured that there was great variety in the texts and the styles which appeared. Many early typefaces were modelled on local writing or derived from various European Gothic scripts, but there were also some derived from documentary scripts like Caxton's, and, particularly in Italy, types modelled on handwritten scripts and calligraphy used by humanists.

Printers congregated in urban centres where there were scholars, ecclesiastics, lawyers, and nobles and professionals who formed their major customer base. Standard works in Latin inherited from the medieval tradition formed the bulk of the earliest printed works, but as books became cheaper, vernacular works (or translations into vernaculars of standard works) began to appear.[citation needed]

Famous examples

Famous incunabula include two from Mainz, the Gutenberg Bible of 1455 and the Peregrinatio in terram sanctam of 1486, printed and illustrated by Erhard Reuwich; the Nuremberg Chronicle written by Hartmann Schedel and printed by Anton Koberger in 1493; and the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili printed by Aldus Manutius with important illustrations by an unknown artist.[citation needed]

Other printers of incunabula were Günther Zainer of Augsburg, Johannes Mentelin and Heinrich Eggestein of Strasbourg, Heinrich Gran of Haguenau, Johann Amerbach of Basel, William Caxton of Bruges and London, and Nicolas Jenson of Venice. The first incunable to have woodcut illustrations was Ulrich Boner's Der Edelstein, printed by Albrecht Pfister in Bamberg in 1461.[16]

A finding in 2015 brought evidence of quires, as claimed by extensive research, printed in 1444–1446, possibly assigned to Procopius Waldvogel in Avignon, France.

Post-incunable

Many incunabula are undated, needing complex bibliographical analysis to place them correctly. The post-incunabula period marks a time of development during which the printed book evolved fully as a mature artefact with a standard format.[17] After about 1540 books tended to conform to a template that included the author, title-page, date, seller, and place of printing. This makes it much easier to identify any particular edition.[18]

As noted above, the end date for identifying a printed book as an incunable is convenient but was chosen arbitrarily; it does not reflect any notable developments in the printing process around the year 1500. Books printed for a number of years after 1500 continued to look much like incunables, with the notable exception of the small format books printed in italic type introduced by Aldus Manutius in 1501. The term post-incunable is sometimes used to refer to books printed "after 1500—how long after, the experts have not yet agreed."[19] For books printed in the UK, the term generally covers 1501–1520, and for books printed in mainland Europe, 1501–1540.[20]

Statistical data

The data in this section were derived from the Incunabula Short-Title Catalogue (ISTC).[21]

The number of printing towns and cities stands at 282. These are situated in some 18 countries in terms of present-day boundaries. In descending order of the number of editions printed in each, these are: Italy, Germany, France, Netherlands, Switzerland, Spain, Belgium, England, Austria, the Czech Republic, Portugal, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, Turkey, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, and Hungary (see diagram).

The following table shows the 20 main 15th century printing locations; as with all data in this section, exact figures are given, but should be treated as close estimates (the total editions recorded in ISTC at August 2016 is 30,518):

| Town or city | No. of editions | % of ISTC recorded editions |

|---|---|---|

| Venice[22] | 3,549 | 12.5 |

| Paris[23] | 2,764 | 9.7 |

| Rome[24] | 1,922 | 6.8 |

| Cologne[25] | 1,530 | 5.4 |

| Lyon[26] | 1,364 | 4.8 |

| Leipzig[27] | 1,337 | 4.7 |

| Augsburg[28] | 1,219 | 4.3 |

| Strasbourg[29] | 1,158 | 4.1 |

| Milan[30] | 1,101 | 3.9 |

| Nuremberg[31] | 1,051 | 3.7 |

| Florence | 801 | 2.8 |

| Basel | 786 | 2.8 |

| Deventer | 613 | 2.2 |

| Bologna | 559 | 2.0 |

| Antwerp | 440 | 1.5 |

| Mainz | 418 | 1.5 |

| Ulm | 398 | 1.4 |

| Speyer | 354 | 1.2 |

| Pavia | 337 | 1.2 |

| Naples | 323 | 1.1 |

| TOTAL | 22,024 | 77.6 |

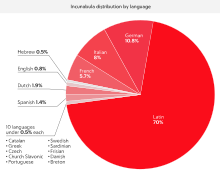

The 18 languages that incunabula are printed in, in descending order, are: Latin, German, Italian, French, Dutch, Spanish, English, Hebrew, Catalan, Czech, Greek, Church Slavonic, Portuguese, Swedish, Breton, Danish, Frisian and Sardinian (see diagram).

Only about one edition in ten (i.e. just over 3,000) has any illustrations, woodcuts or metalcuts.

The "commonest" incunable is Schedel's Nuremberg Chronicle ("Liber Chronicarum") of 1493, with about 1,250 surviving copies (which is also the most heavily illustrated). Many incunabula are unique, but on average about 18 copies survive of each. This makes the Gutenberg Bible, at 48 or 49 known copies, a relatively common (though extremely valuable) edition. Counting extant incunabula is complicated by the fact that most libraries consider a single volume of a multi-volume work as a separate item, as well as fragments or copies lacking more than half the total leaves. A complete incunable may consist of a slip, or up to ten volumes.[32]

In terms of format, the 30,000-odd editions comprise: 2,000 broadsides, 9,000 folios, 15,000 quartos, 3,000 octavos, 18 12mos, 230 16mos, 20 32mos, and 3 64mos.

ISTC at present cites 528 extant copies of books printed by Caxton, which together with 128 fragments makes 656 in total, though many are broadsides or very imperfect (incomplete).[citation needed]

Apart from migration to mainly North American and Japanese universities, there has been little movement of incunabula in the last five centuries. None were printed in the Southern Hemisphere, and the latter appears to possess less than 2,000 copies, about 97.75% remain north of the equator. However, many incunabula are sold at auction or through the rare book trade every year.[citation needed]

Major collections

The British Library's Incunabula Short Title Catalogue now records over 29,000 titles, of which around 27,400 are incunabula editions (not all unique works). Studies of incunabula began in the 17th century. Michel Maittaire (1667–1747) and Georg Wolfgang Panzer (1729–1805) arranged printed material chronologically in annals format, and in the first half of the 19th century, Ludwig Hain published the Repertorium bibliographicum—a checklist of incunabula arranged alphabetically by author: "Hain numbers" are still a reference point. Hain was expanded in subsequent editions, by Walter A. Copinger and Dietrich Reichling, but it is being superseded by the authoritative modern listing, a German catalogue, the Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke, which has been under way since 1925 and is still being compiled at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. North American holdings were listed by Frederick R. Goff and a worldwide union catalogue is provided by the Incunabula Short Title Catalogue.[33]

Notable collections with more than 1,000 incunabula include:

See also

References

External links

- Centre for the History of the Book

- British Library worldwide Incunabula Short Title Catalogue Archived 12 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke (GW), partially English version

- History of Incunabula Studies

- UIUC Rare Book & Manuscript Library

- Grand Valley State University Incunabula & 16th Century Printing digital collections

- Incunable Collection at the US Library of Congress

- Digital facsimiles of several incunabula Archived 8 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine from the website of the Linda Hall Library

- Kristian Jensen (2016). "Introduction to the study of incunabula". Lyon: Ecole Nationale Superieure des Sciences de l'information et des Bibliotheques, Institut d'histoire du livre. Archived from the original on 27 November 2017. (Includes annotated bibliography)

- "Rinascimento: Manuscripts & Incunabula". Research Guides. US: Harvard University Library.

- Pollard, Alfred W. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). pp. 369–370.

- "An Introduction to Incunabula". Barber, Phil. Retrieved 6 July 2017.