Information fluctuation complexity is an information-theoretic quantity defined as the fluctuation of information about entropy. It is derivable from fluctuations in the predominance of order and chaos in a dynamic system and has been used as a measure of complexity in many diverse fields. It was introduced in a 1993 paper by Bates and Shepard.[1]

Definition

The information fluctuation complexity of a discrete dynamic system is a function of the probability distribution of its states when it is subject to random external input data. The purpose of driving the system with a rich information source such as a random number generator or a white noise signal is to probe the internal dynamics of the system in much the same way as a frequency-rich impulse is used in signal processing.

If a system has

where

The information fluctuation complexity of the system is defined as the standard deviation or fluctuation of

or

The fluctuation of state information

Fluctuation of information allows for memory and computation

As a complex dynamic system evolves in time, how it transitions between states depends on external stimuli in an irregular way. At times it may be more sensitive to external stimuli (unstable) and at other times less sensitive (stable). If a particular state has several possible next-states, external information determines which one will be next and the system gains that information by following a particular trajectory in state space. But if several different states all lead to the same next-state, then upon entering the next-state the system loses information about which state preceded it. Thus, a complex system exhibits alternating information gain and loss as it evolves in time. The alternation or fluctuation of information is equivalent to remembering and forgetting — temporary information storage or memory — an essential feature of non-trivial computation.

The gain or loss of information associated with transitions between states can be related to state information. The net information gain of a transition from state

Here

Eliminating the conditional probabilities:

Therefore, the net information gained by the system as a result of the transition depends only on the increase in state information from the initial to the final state. It can be shown that this is true even for multiple consecutive transitions.[1]

It may be useful to compute the standard deviation of

Chaos and order

A dynamic system that is sensitive to external information (unstable) exhibits chaotic behavior whereas one that is insensitive to external information (stable) exhibits orderly behavior. A complex system exhibits both behaviors, fluctuating between them in dynamic balance when subject to a rich information source. The degree of fluctuation is quantified by

Example: rule 110 variant of the elementary cellular automaton[2]

The rule 110 variant of the elementary cellular automaton has been proven to be capable of universal computation. The proof is based on the existence and interactions of cohesive and self-perpetuating cell patterns known as gliders or spaceships (examples of emergent phenomena associated with complex systems), that imply the capability of groups of automaton cells to remember that a glider is passing through them. It is therefore to be expected that there will be memory loops in state space resulting from alternations of information gain and loss, instability and stability, chaos and order.

Consider a 3-cell group of adjacent automaton cells that obey rule 110: end-center-end. The next state of the center cell depends on the present state of itself and the end cells as specified by the rule:

| 3-cell group | 1-1-1 | 1-1-0 | 1-0-1 | 1-0-0 | 0-1-1 | 0-1-0 | 0-0-1 | 0-0-0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| next center cell | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

To calculate the information fluctuation complexity of this system, attach a driver cell to each end of the 3-cell group to provide a random external stimulus like so, driver→end-center-end←driver, such that the rule can be applied to the two end cells. Next, determine what the next state is for each possible present state and for each possible combination of driver cell contents, to determine the forward conditional probabilities.

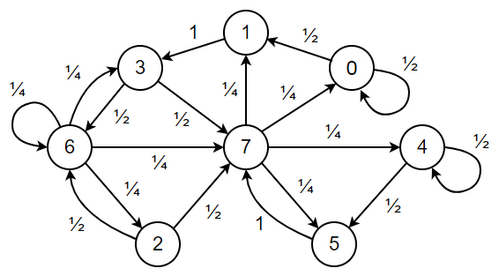

The state diagram of this system is depicted below, with circles representing the states and arrows representing transitions between states. The eight states of this system, 1-1-1 to 0-0-0 are labeled with the octal equivalent of the 3-bit contents of the 3-cell group: 7 to 0. The transition arrows are labeled with forward conditional probabilities. Notice that there is variability in the divergence and convergence of arrows corresponding to variability in gain and loss of information from the driver cells.

The forward conditional probabilities are determined by the proportion of possible driver cell contents that drive a particular transition. For example, for the four possible combinations of two driver cell contents, state 7 leads to states 5, 4, 1 and 0 and so

The state probabilities are related by

and

These linear algebraic equations can be solved manually or with the aid of a computer program for the state probabilities, with the following results:[2]

| p0 | p1 | p2 | p3 | p4 | p5 | p6 | p7 |

| 2/17 | 2/17 | 1/34 | 5/34 | 2/17 | 2/17 | 2/17 | 4/17 |

Information entropy and complexity can then be calculated from the state probabilities:

Note that the maximum possible entropy for eight states is

An alternative method can be used to obtain the state probabilities when the analytical method used above is unfeasible. Simply drive the system at its inputs (the driver cells) with a random source for many generations and observe the state probabilities empirically. When this is done via computer simulation for 10 million generations the results are as follows:[2]

| number of cells | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(bits) (bits) | 2.86 | 3.81 | 4.73 | 5.66 | 6.56 | 7.47 | 8.34 | 9.25 | 10.09 | 10.97 | 11.78 |

(bits) (bits) | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.15 |

| 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

Since both

In the paper by Bates and Shepard,[1]

Applications

Although the derivation of the information fluctuation complexity formula is based on information fluctuations in a dynamic system, the formula depends only on state probabilities and so is also applicable to any probability distribution, including those derived from static images or text.

Over the years the original paper[1] has been referred to by researchers in many diverse fields: complexity theory,[3] complex systems science,[4] complex networks,[5] chaotic dynamics,[6] many-body localization entanglement,[7] environmental engineering,[8] ecological complexity,[9] ecological time-series analysis,[10] ecosystem sustainability,[11] air[12] and water[13] pollution, hydrological wavelet analysis,[14] soil water flow,[15] soil moisture,[16] headwater runoff,[17] groundwater depth,[18] air traffic control,[19] flow patterns[20] and flood events,[21] topology,[22] economics,[23] market forecasting of metal[24] and electricity[25] prices, health informatics,[26] human cognition,[27] human gait kinematics,[28] neurology,[29] EEG analysis,[30] education,[31] investing,[32] artificial life[33] and aesthetics.[34]