Kalimpong district is a district in the state of West Bengal, India. In 2017, it was carved out as a separate district to become the 21st district of West Bengal.[2][3]

Kalimpong | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top-left: Mangal Dham Mandir, Morgan House in Kalimpong, Hanuman Mandir, view from Rishyap, Neora Valley National Park | |

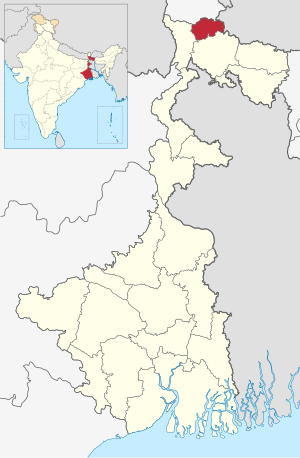

Location of Kalimpong in West Bengal | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Division | Jalpaiguri |

| Headquarters | Kalimpong |

| Government | |

| • Lok Sabha constituencies | Darjeeling (shared with Darjeeling district) |

| • Vidhan Sabha constituencies | Kalimpong |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,053.60 km2 (406.80 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 251,642 |

| • Density | 240/km2 (620/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| Website | kalimpong |

The district is headquartered at Kalimpong, which grew to prominence as a market town for Indo-Tibetan trade during the British period. It is bounded by Pakyong district of Sikkim in the north, Bhutan in the east, Darjeeling district in the west, and Jalpaiguri district in the south. The district consists of the Kalimpong municipality and four community development blocks: Kalimpong I, Kalimpong II, Gorubathan and Pedong.

Area

Apart from the Kalimpong municipality that consists of 23 wards, the district contains rural areas of 42 gram panchayats under four community development blocks: Kalimpong I, Kalimpong II, Gorubathan and Pedong.[4]

Kalimpong district has an area of 1,053.60 km2 (406.80 sq mi), with Kalimpong I block having an area of 360.46 km2 (139.17 sq mi); Kalimpong II block an area of 241.26 km2 (93.15 sq mi); Gorubathan block an area of 442.72 km2 (170.94 sq mi); and Kalimpong Municipality an area of 9.16 km2 (3.54 sq mi).[1]

History

What is now Kalimpong district was originally Sikkimese territory.[5][6] It was controlled through two hill forts in the region, at Damsang[a] and Daling[b] (or Dalingkot, meaning "Daling fort"). The region itself seems to have been referred to as Dalingkot.[7] In 1718, the Kingdom of Bhutan annexed this territory, and ruled it for the following 150 years.[8][9] The area was sparsely populated by Indian Hindus, Lepchas, and migrant Bhutia, Limbu and Kirati tribes.

After the Anglo-Bhutan War in 1864, the Treaty of Sinchula (1865) was signed, in which certain "hill territory to east of the Teesta River" was ceded to British India.[5] The precise territory was unspecified but included the fort of Dalingkot. In 1866–1867, British surveyors demarcated the area, and set the Di Chu and Ni Chu rivers as the eastern and northeastern boundaries.[10][11]

The ceded territory was added to the Western Duars district at first, and later transferred to the Darjeeling district of the Bengal province in 1866.[8] It was referred to as the "tract of Dalingkot" or "tract of Damsang", after the hill forts through which it had been administered in the past.[11][12] At that time, Kalimpong was a small hamlet, with only two or three families known to reside there.[13] However the neighbourhood of Kalimpong was well-populated with several villages, as recorded by Ashley Eden during a mission to Bhutan in 1864. Eden mentioned that the people there were well-disposed to the British administration and had frequently traded with the Darjeeling area to the west of Teesta in defiance of the Bhutanese authorities.[14]

The temperate climate prompted the British to develop the town as an alternative hill station to Darjeeling, to escape the scorching summer heat in the plains. Kalimpong's proximity to the Nathu La and Jelep La passes for trading with Tibet was an added advantage. It soon became an important trading outpost in the trade of furs, wools and food grains between India and Tibet.[15] The increase in commerce attracted large numbers of Nepalis from neighbouring Nepal and also the lower regions of Sikkim where Nepalis had been residing since the Gorkha invasion of Sikkim in 1790. The movement of people into the area transformed Kalimpong from a small hamlet with a few houses, to a thriving town with economic prosperity. Britain assigned a plot within Kalimpong to the influential Bhutanese Dorji family, through which trade and relations with Bhutan flowed. This later became the Bhutan House, a Bhutanese administrative and cultural centre.[16][17][18]

The arrival of Scottish missionaries saw the construction of schools and welfare centres for the British.[13] Rev. W. Macfarlane in the early 1870s established the first schools in the area.[13] The Scottish University Mission Institution was opened in 1886, followed by the Kalimpong Girls High School. In 1900, Reverend J.A. Graham founded the Dr. Graham's Homes for destitute Anglo-Indian students.[13] The young missionary (and aspiring writer and poet) Aeneas Francon Williams, aged 24, arrived in Kalimpong in 1910 to take up the post of assistant schoolmaster at Dr. Graham's Homes,[19] where he later became Bursar and remained working at the school for the next fourteen years.[20] From 1907 onwards, most schools in Kalimpong had started offering education to Indian students. By 1911, the population comprised many ethnic groups, including Nepalis, Lepchas, Tibetans, Muslims, the Anglo-Indian communities. Hence by 1911, the population had swollen to 7,880.[13]

Following Indian independence in 1947, Kalimpong remained in West Bengal, the part of Bengal allocated to India during the Paritiion. With China's annexation of Tibet in 1950, many Buddhist monks fled Tibet and established monasteries in Kalimpong. These monks brought rare Buddhist scriptures with them. In 1962, the permanent closure of Jelep La after the Sino-Indian War disrupted trade between Tibet and India, and led to a slowdown in Kalimpong's economy. In 1976, the visiting Dalai Lama consecrated the Zang Dhok Palri Phodang monastery, which houses many of the Tibetan Buddhist scriptures.[13]

Between 1986 and 1988, the demand for a separate state of Gorkhaland and Kamtapur based on ethnic lines grew strong. Riots between the Gorkha National Liberation Front (GNLF) and the West Bengal government reached a stand-off after a forty-day strike. The town was virtually under siege, and the state government called in the Indian army to maintain law and order. This led to the formation of the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council, a body that was given semi-autonomous powers to govern the Darjeeling district, except the area under the Siliguri subdivision. Since 2007, the demand for a separate Gorkhaland state has been revived by the Gorkha Janmukti Morcha and its supporters in the Darjeeling hills.[21] The Kamtapur People's Party and its supporters' movement for a separate Kamtapur state covering North Bengal have gained momentum.[22]

Blocks

Kalimpong I block

The Kalimpong I block consists of 18 gram panchayats; Bong, Kalimpong, Samalbong, Tista, Dr. Graham's Homes, Lower Echhay, Samthar, Neembong, Dungra, Upper Echhay, Seokbir, Bhalukhop, Yangmakum, Pabringtar, Sindebong, Kafer Kanke Bong, Pudung and Tashiding.[4] This block has one police station at Kalimpong.[23] The block is headquartered in Kalimpong.[24]

Kalimpong II block

The Kalimpong II block consists of 7 gram panchayats, namely Dalapchand, Gitdabling, Lava-Gitabeong, Lolay, Payong, Shangse, and Shantuk.[4] This block is served by Kalimpong police station.[23] The block is headquartered in Algarah.[24]

Gorubathan block

The Gorubathan block consists of 11 gram panchayats, namely Dalim, Gorubathan–I, Gorubathan–II, Patengodak, Todey Tangta, Kumai, Pokhreybong, Samsing, Aahaley, Nim and Rongo.[4] This block has two police stations: Gorubathan and Jaldhaka.[23] The block is headquartered in Fagu.[24]

Pedong block

The Pedong block consists of 6 gram panchayats, namely Kage, Kashyong, Lingsey, Lingseykha, Pedong and Syakiyong.This block is served by Kalimpong police station. The block is headquartered in Pedong.

Legislative segments

As per order of the Delimitation Commission in respect of the delimitation of constituencies in West Bengal, the whole area under the district of Kalimpong (formerly Kalimpong subdivision), namely the Kalimpong municipality and the three blocks of Kalimpong–I, Kalimpong–II and Gorubathan together constitutes the Kalimpong assembly constituency of West Bengal. This constituency is part of Darjeeling Lok Sabha constituency. Darjeeling is represented by Neeraj Zimba of the Bharatiya Janata Party, while Kalimpong Assembly constituency is represented by Ruden Sada Lepcha of the Gorkha Janmukti Morcha (Tamang faction).[25]

Demographics

According to the 2011 census, Kalimpong district (enumerated as Kalimpong subdivision then) has a population of 251,642. Kalimpong I block had a population of 74,746; Kalimpong II block had a population of 66,830; Gorubathan block had a population of 60,663; and Kalimpong Municipality had a population of 49,403. Kalimpong district has a sex ratio of 959 females per 1000 males. 56,192 (22.33%) live in urban areas. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes made up 16,433 (6.53%) and 74,976 (29.79%) of the population respectively.[1]

Religion

| Religion | Population (1941)[27]: 90–91 | Percentage (1941) | Population (2011)[26] | Percentage (2011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Hinduism  | 35,928 | 45.45% | 153,355 | 60.94% |

Tribal religion  | 31,674 | 40.07% | 3,243 | 1.29% |

Christianity  | 714 | 0.9% | 37,453 | 14.88% |

Islam  | 324 | 0.41% | 3,998 | 1.59% |

Buddhism  | --- | --- | 52,688 | 20.94% |

| Others[c] | 10,402 | 13.16% | 905 | 0.36% |

| Total Population | 79,042 | 100% | 251,642 | 100% |

According to the 2011 census, Hindus numbered 153,355 (60.94%), Buddhists numbered 52,688 (20.94%), Christians numbered 37,453 (14.88%). Muslims numbered 3,998 (1.59%) of the population, while traditional faiths (such as Kirat Mundhum) were 3,243 (1.29%).[26]

Languages

At the time of the 1951 census, only 24% of those now living in Kalimpong district spoke Nepali as their mother tongue. Most of the population spoke a variety of other languages such as Rai, Limbu, Lepcha and Tamang, although nearly all could speak Nepali as a second language.[30] By 1961, the proportion of people in Kalimpong returning Nepali as their mother tongue had jumped to 75%. This was accompanied by a dramatic fall in the numbers of other languages spoken by the variety of ethnic groups in the hills.[31]

At the time of the 2011 census, 87.61% of the population spoke Nepali, 3.18% Hindi, 2.67% Lepcha, 1.16% Bhojpuri and 5.38% Others languages as their first language.[28][29]

Flora and fauna

Kalimpong district is home to the Neora Valley National Park, which has an area of 159.89 km2 (61.73 sq mi).[32] Mammals reported from this area are Indian leopard, five viverrid species, Asiatic black bear, sloth bear, Asian golden cat, wild boar, leopard cat, goral, serow, barking deer, sambar deer, flying squirrel, tahr, red panda and clouded leopard.[33]

Transport

Roadways

National Highways

- National Highway 10 connecting Siliguri to Gangtok, lies in Kalimpong District from Kalijhora to Atal Setu Bridge, Rangpo via Teesta Bazaar, Rambi Bazar and Melli.

- National Highway-717A Connecting Bagrakote to Gangtok lies in Kalimpong district from Bagrakote to Resi Sikkim border, via Labha, Algarah, Pedong, and Kataray Bazar.[34]

- National Highway 17 connecting Sevoke to Guwahati lies in Kalimpong district at Coronation Bridge - Mongpong area.

Railway

The currently functioning nearest railway station from Kalimpong district is Sivok railway station of Darjeeling district and Bagrakote Railway Station of Jalpaiguri district.The nearest major railway stations are Malbazar Junction, Siliguri Junction and New Jalpaiguri railway station.

The under construction Sevoke - Rangpo railway line lies in Kalimpong district from Kalijhora to

- Melli Railway Station via the following stations:

- Riyang Railway Station and

- Tista Bazaar Railway Station

Airways

Bagdogra Airport is the nearest airport from southern parts of Kalimpong district, and Pakyong Airport is the nearest airport from northern areas of Kalimpong district.

Rivers

The major rivers flowing through Kalimpong district are River Teesta, River Jaldhaka and River Rangpo. Other rivers are Relli Khola, Riyang Khola,Murti Khola, Reshi Khola, Chel Khola, River Ghish, Bindu Khola, Les Khola, Neora Khola etc.

Notes

References

Bibliography

- Rennie, Surgeon (1866), Bhotan and the Dooar War, John Murray – via archive.org

- Roy, D. C. (ed.), Survey and Settlement of the Western Duarsl in the District of Jalpaiguri 1889-1895, D. H. E. Sunder, Siliguri: N. L. Publishers – via archive.org

- Samanta, Amiya K. (2000). Gorkhaland Movement: A Study in Ethnic Separatism. APH Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7648-166-3.

External links

- Official website

- Kalimpong district, OpenStreetMap, retrieved 2 December 2021.