LK-99 (from the Lee-Kim 1999 research),[2] also called PCPOSOS,[3] is a gray–black, polycrystalline compound, identified as a copper-doped lead‒oxyapatite. A team from Korea University led by Lee Sukbae (이석배) and Kim Ji-Hoon (김지훈) began studying this material as a potential superconductor starting in 1999.[4]: 1 In July 2023, they published preprints claiming that it acts as a room-temperature superconductor[4]: 8 at temperatures of up to 400 K (127 °C; 260 °F) at ambient pressure.[2][5][4]: 1

| |

3D structure | |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| CuO25P6Pb9 | |

| Molar mass | 2514.2 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Purple crystal when pure[1] |

| Density | ≈6.699 g/cm3 |

| Structure | |

| hexagonal | |

| P63/m, No. 176 | |

a = 9.843 Å, c = 7.428 Å | |

Lattice volume (V) | 623.2 Å3 |

Formula units (Z) | 1 |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds | Oxypyromorphite (lead apatite) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

Many different researchers have attempted to replicate the work, and were able to reach initial results within weeks, as the process of producing the material is relatively straightforward.[6] By mid-August 2023, the consensus[1] was that LK-99 is not a superconductor at any temperature, and is an insulator in pure form.[7][8][9]

As of 12 February 2024, no replications had gone through the peer review process of a journal, but some had been reviewed by a materials science lab. A number of replication attempts identified non-superconducting ferromagnetic and diamagnetic causes for observations that suggested superconductivity. A prominent cause was a copper sulfide impurity[10] occurring during the proposed synthesis, which can produce resistance drops, lambda transition in heat capacity, and magnetic response in small samples.[11][12][10][13][14][15][16]

After the initial preprints were published, Lee claimed they were incomplete,[17] and coauthor Kim Hyun-Tak (김현탁) said one of the papers contained flaws.[18]

Chemical properties and structure

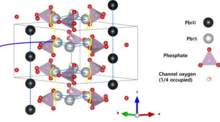

The chemical composition of LK-99 is approximately Pb9Cu(PO4)6O, in which— compared to pure lead-apatite (Pb10(PO4)6O)[19]: 5 — approximately one quarter of Pb(II) ions in position 2 of the apatite structure are replaced by Cu(II) ions.[4]: 9

The structure is similar to that of apatite, space group P63/m (No. 176).

Synthesis

Lee et al. provide a method for chemical synthesis of LK-99[19]: 2 in three steps. First they produce lanarkite from a 1:1 molar mixing of lead(II) oxide (PbO) and lead(II) sulfate (Pb(SO4)) powders, and heating at 725 °C (1,000 K; 1,340 °F) for 24 hours:

- PbO + Pb(SO4) → Pb2(SO4)O.

Then, copper(I) phosphide (Cu3P) is produced by mixing copper (Cu) and phosphorus (P) powders in a 3:1 molar ratio in a sealed tube under a vacuum and heated to 550 °C (820 K; 1,000 °F) for 48 hours:[19]: 3

- 3 Cu + P → Cu3P.

Then, lanarkite and copper phosphide crystals are ground into a powder, placed in a sealed tube under a vacuum, and heated to 925 °C (1,200 K; 1,700 °F) for between 5‒20 hours:[19]: 3

- Pb2(SO4)O + Cu3P → Pb10-xCux(PO4)6O + S (g), where 0.9 < x < 1.1.

There were a number of problems with the above synthesis from the initial paper. The reaction is not balanced, and others reported the presence of copper(I) sulfide (Cu2S) as well.[20][12] For

- 5 Pb2SO4O + 6 Cu3P → Pb9Cu(PO4)6O + 5 Cu2S + Pb + 7 Cu.[21]

Many syntheses produced fragmentary results in different phases, where some of the resulting fragments were responsive to magnetic fields, other fragments were not.[22] The first synthesis to produce pure crystals found them to be diamagnetic insulators.[23]

Physical properties

Some small LK-99 samples were reported to show strong diamagnetic properties, including a response confusingly[24] referred to as "partial levitation" over a magnet.[19] This was misinterpreted by some as a sign of superconductivity, although it is a sign of regular diamagnetism or ferromagnetism.

While initial preprints claimed the material was a room-temperature superconductor,[19]: 1 they did not report observing any definitive features of superconductivity, such as zero resistance, the Meissner effect, flux pinning, AC magnetic susceptibility, the Josephson effect, a temperature-dependent critical field and current, or a sudden jump in specific heat around the critical temperature.[25]

As it is common for a new material to spuriously seem like a potential candidate for high-temperature superconductivity,[14] thorough experimental reports normally demonstrate a number of these expected properties. As of 15 October 2023,[update] not one of these properties had been observed by the original experiment or any replications.[26]

Proposed mechanism for superconductivity

Partial replacement of Pb2+ ions with smaller Cu2+ ions is said to cause a 0.48% reduction in volume, creating internal stress in the material,[4]: 8 causing a heterojunction quantum well between the Pb(1) and oxygen within the phosphate ([PO4]3−). This quantum well was proposed to be superconducting[4]: 10 , based on a 2021 paper[27] by Kim Hyun-Tak describing a novel and complicated theory combining ideas from a classical theory of metal-insulator transitions,[28] the standard Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer theory, and the theory of hole superconductivity[29] by J.E.Hirsch.

Response

On 31 July 2023, Sinéad Griffin of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory analyzed LK-99 with density functional theory (DFT), showing that its structure would have correlated isolated flat bands, and suggesting this might contribute to superconductivity.[30] However, while other researchers agreed with the DFT analysis, a number suggested that this was not compatible with superconductivity, and that a structure different from what was described in Lee, et al. would be necessary.[31]

Analyses by industrial and experimental physicists noted experimental and theoretical shortcomings of the published works.[32] Shortcomings included the lack of phase diagrams[29] spanning temperature, stoichiometry,[33] and stress; the lack of pathways for the very high Tc of LK-99 compared to prior heavy fermion superconductors; the absence of flux pinning in any observations; the possibility of stochastic conductive artifacts[34] in conductivity measurements; the high resistance and low current capacity of the alleged superconducting state; and the lack of direct transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of the materials.

Compound name

The name LK-99 comes from the initials of discoverers Lee and Kim, and the year of discovery (1999).[2] The pair had worked with Tong-Seek Chair (최동식) at Korea University in the 1990s.[35]

In 2008, they founded the Quantum Energy Research Centre (퀀텀 에너지연구소; also known as Q-Centre) with other researchers from Korea University .[17] Lee would later become CEO of Q-Centre, and Kim would become director of research and development.

Publication history

Lee has stated that in 2020, an initial paper was submitted to Nature, but was rejected.[35] Similarly presented research on room-temperature superconductors (but a completely different chemical system) by Ranga P. Dias had been published in Nature earlier that year, and received with skepticism—Dias's paper would subsequently be retracted in 2022 after its data was questioned as having been falsified.[36]

In 2020, Lee and Kim Ji-Hoon filed a patent application.[37] A second patent application (additionally listing Young-Wan Kwon), was filed in 2021, which was published on 3 March 2023.[38] A World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) patent was also published on 2 March 2023.[39] On 4 April 2023, a Korean trademark application for "LK-99" was filed by the Q-Centre.[40]

Scholarly articles and preprints

A series of academic publications summarizing initial findings came out in 2023, with a total of seven authors across four publications.

On 31 March 2023, a Korean-language paper, "Consideration for the development of room-temperature ambient-pressure superconductor (LK-99)", was submitted to the Korean Journal of Crystal Growth and Crystal Technology.[5] It was accepted on 18 April, but was not widely read until three months later.

On 22 July 2023, two preprints appeared on arXiv. The first was submitted by Young-Wan Kwon, and listed Kwon, former Q-Centre CTO, as third author.[4] The second preprint was submitted only 2 hours later by Kim Hyun-Tak, former principal researcher at the Electronics & Telecommunications Research Institute and professor at the College of William & Mary, listing himself as third author, as well as three new authors.[19][41]

On 23 July, the findings were also submitted by Lee to APL Materials for peer review.[35][17] On 3 August 2023, a newly-formed Korean LK-99 Verification Committee requested a high-quality sample from the original research team. The team responded that they would only provide the sample once the review process of their APL paper was completed, expected to take several weeks or months.[42]

On 31 July 2023, a group led by Kapil Kumar published a preprint on arXiv documenting their replication attempts, which confirmed the structure using X-ray crystallography (XRD) but failed to find strong diamagnetism.[20]

On 16 August 2023, Nature published an article declaring that LK-99 had been demonstrated to not be a superconductor, but rather an insulator. It cited statements by an condensed matter experimentalist at the University of California, Davis, and several studies previewed in August 2023.[1]

Other discussion by authors

On 26 July 2023, Kim Hyun-Tak stated in an interview with the New Scientist that the first paper submitted by Kwon contained "many defects" and was submitted without his permission.[33][41]

On 28 July 2023, Kwon presented the findings at a symposium held at Korea University.[43][44][45] That same day, Yonhap News Agency published an article quoting an official from Korea University as saying that Kwon was no longer in contact with the university.[17] The article also quoted Lee saying that Kwon had left the Q-Centre Research Institute four months previously.[17]

On the same day, Kim Hyun-Tak provided The New York Times with a new video presumably showing a sample displaying strong signs of diamagnetism.[2] The video appears to show a sample different to the one in the original preprint. On 4 August 2023, he informed SBS News that high-quality LK-99 samples may exhibit diamagnetism over 5,000 times greater than graphite, which he claimed would be inexplicable unless the substance is a superconductor.[46]

Response

Materials scientists and superconductor researchers responded with skepticism.[18][47] The highest-temperature superconductors known at the time of publication had a critical temperature of 250 K (−23 °C; −10 °F) at pressures of over 170 gigapascals (1,680,000 atm; 24,700,000 psi). The highest-temperature superconductors at atmospheric pressure (1 atm) had a critical temperature of at most 150 K (−123 °C; −190 °F).

On 2 August 2023, the The Korean Society of Superconductivity and Cryogenics established a verification committee as a response to the controversy and unverified claims of LK-99, in order to arrive at conclusions over these claims. The verification committee is headed by Kim Chang-Young of Seoul National University and consists of members of the university, Sungkyunkwan University and Pohang University of Science and Technology. Upon formation, the verification committee did not agree that the two 22 July arXiv papers by Lee et al. or the publicly available videos at the time supported the claim of LK-99 being a superconductor.[41][48]

As of 15 August 2023,[update] the measured properties do not prove that LK-99 is a superconductor. The published material does not explain how the LK-99's magnetisation can change, demonstrate its specific heat capacity, or demonstrate it crossing its transition temperature.[18] A more likely explanation for LK-99's magnetic response is a mix of ferromagnetism and non-superconductive diamagnetism.[41][16][49] A number of studies found that copper(I) sulfide contamination common to the synthesis process could closely replicate the observations that inspired the initial preprints.[10][11]

Public response

The claims in the 22 July papers by Lee et al. went viral on social media platforms the following week.[6][50] The viral nature of the claim resulted in posts from users using pseudonyms from Russia and China claiming to have replicated LK-99 on both Twitter and Zhihu.[51] Other viral videos described themselves as having replicated samples of LK-99 "partially levitating", most of which were found to be fake.[47]

Scientists interviewed by the press remained skeptical,[52][53] because of the quality of both the original preprints, the lack of purity in the sample they reported, and the legitimacy of the claim after the failure of previous claims of room temperature superconductivity did not show legitimacy (such as the Ranga Dias affair).[41] The Korean Society of Superconductivity and Cryogenics expressed concern on the social and economic impacts of the preliminary and unverified LK-99 research.[54]

A video from Huazhong University of Science and Technology uploaded on 1 August 2023 by a postdoctoral researcher on the team of Chang Haixin,[41] apparently showed a micrometre-sized sample of LK-99 partially levitating. This went viral on Chinese social media, becoming the most viewed video on Bilibili by the next day,[55][41] and a prediction market briefly put the chance of successful replication at 60%.[56] A researcher from the Chinese Academy of Sciences refused to comment on the video for the press, dismissing the claim as "ridiculous".[55]

In early August, people began to create memes about "floating rocks",[57] and there was a brief surge in Korean and Chinese technology stocks,[58][59][60] despite warnings from the Korean stock exchange against speculative bets in light of the excitement around LK-99,[54] which eventually fell on August 8.[61] Following the publication of the Nature article on August 16 that proclaimed LK-99 is not a superconductor,[1] South Korean superconductor stocks fell further, as the interest about LK-99 from investors in previous weeks disappeared.[62]

Replication attempts

After the July 2023 publication's release, independent groups reported that they had begun attempting to reproduce the synthesis, with initial results expected within weeks.[6]

As of 15 August 2023,[update] no replication attempts had yet been peer-reviewed by a journal. Of the non-peer-reviewed attempts, over 15 notable labs have published results that failed to observe any superconductivity, and a few have observed magnetic response in small fragments that could be explained by normal diamagnetism or ferromagnetism. Some demonstrated and replicated alternate causes of the observations in the original papers: Copper-deficient copper (I) sulfide[10] has a known phase transition at 377 K (104 °C; 219 °F) from a low-temperature phase to a high-temperature superionic phase, with a sharp rise in resistivity[11][10] and a λ-like-feature in the heat capacity.[10] Furthermore, Cu2S is diamagnetic.

Only one attempt observed any sign of superconductivity: Southeast University claimed to measure very low resistance in a flake of LK-99, in one of four synthesis attempts, below a temperature of 110 K (−163 °C; −262 °F).[2][63] Doubts were expressed by experts in the field, as they saw no dropoff to zero resistance, and used crude instruments that could not measure resistance below 10 μΩ (too high to distinguish superconductivity from less exotic low-temperature conductivity), and had large measurement artifacts.[47][64]

Some replication efforts gained global visibility, with the aid of online replication trackers that catalogued new announcements and status updates.[51][26]

Experimental studies

Selected experimental studies.

Results Key: Success Partial success Partial failure Failure

| Group | Country/region | Status | Results | Publication notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Planck (Solid State) |  Germany Germany | Preliminary | Produced pure LK-99 samples with floating zone technique. Purple crystals with high resistance, no magnetic response. | |

| Huazhong Tech |  China China | Preliminary | Measured diamagnetism of micron-sized flakes. Non-zero resistance, purity of sample was important. | |

| Beihang University | Preliminary | No diamagnetism observed. High resistivity not consistent with superconductivity. | ||

| Southeast University | Preliminary | Structure confirmed by XRD. Resistance of one mm-sized sample dropped from 0.1 Ω at room temperature to noise level (10−5 Ω) at 110 K and below. No observed Meissner effect. | ||

| Peking University | Preliminary | No Meissner effect nor zero resistivity observed. | ||

| Chinese Academy of Sciences (Condensed Matter) | Preliminary | No superconductivity observed. Proposed that resistivity drop and strong diamagnetism could be due to a phase change of Cu2S impurities. | ||

| Central South University, South China Tech, and UESTC | Preliminary | Low-field microwave absorption below 250 K resembles superconductivity, but is destroyed by rotation in an external field. Theoretical models suggest the external field excites a fragile superconducting state to a vortex glass, followed by a ~2-day-long relaxation to the ground state. |

| |

| DIPC, Princeton, Max Planck (Chemical Physics) |  Spain, Spain,  USA, USA,  Germany Germany | Preliminary | Synthesized LK-99 found to be a multiphase material. Performed single-crystal analysis with XRD. Tested four different Cu dopings, some found to be magnetic but none was superconducting. | |

| University of Manchester |  United Kingdom United Kingdom | Preliminary | Synthesized and characterized samples of LK-99, no superconductivity. |

|

| CSIR-NPLI |  India India | Preliminary | Initial attempt: Structure confirmed by XRD, no diamagnetism or superconductivity. Second attempt: strong diamagnetism in a fragment. | |

| Varda Space & USC |  United States United States | Preliminary | Only a few LK-99 fragments responded to magnetic field. Analysis showed impurities of Iron and Cu2S, which could explain magnetic response rather than superconductivity. | |

| UC–Boulder | Unpublished | Samples have failed tests for superconductivity. |

| |

| Argonne | Unknown | Not reported | ||

| Korea University, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul National University |  South Korea South Korea | Unknown | Not reported | |

| Chinese Academy of Sciences (Process Engineering), South China Tech, Beijing 2060, Huazhong Tech, Fuzhou University, Tokai University, and USTB |  Mainland China、 Mainland China、 Japan Japan | Preliminary | Modified LK-99 exhibited diamagnetic direct current magnetization occurred under a 25 Oe magnetic field, but significant bifurcation between zero field cooling (ZFC) and field cooling (FC) measurements, and paramagnetism at a 200 Oe magnetic field. A glassy memory effect was discovered while cooling. Typical hysteresis loops of superconductors were detected below 250 K, and there was asymmetry between forward and reverse magnetic field scans. Possible Meissner effect at room temperature. | |

| Chinese Academy of Sciences (Process Engineering),Huazhong University of Science and Technology, University of Science and Technology Beijing, South China University of Technology, Fuzhou University, Tokai University and University of Science and Technology of China | Preliminary | 1. Proposed a new lk99 structure theory 2. The resistance of lk99 material was measured, which is roughly equivalent to copper. 3. Observed strange metal phenomena | arXiv:Observation of diamagnetic strange-metal phase in sulfur-copper codoped lead apatite |

Theoretical studies

In the initial papers, the theoretical explanations for potential mechanisms of superconductivity in LK-99 were incomplete. Later analyses by other labs added simulations and theoretical evaluations of the material's electronic properties from first principles.

Selected theoretical studies:

| Group | Country | Result | Publication notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese Academy of Sciences (SYNL) |  China China | First-principles study of the electronic structure of LK-99 and other variants. Expresses no opinion on room-temp superconductivity. | arXiv: Junwen Lai, et al.[89] Media mentions:[90] |

| Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory |  United States United States | Density functional theory analysis on a simplified 3D structure explored possible electronic structure that could favor superconductivity, suggests slightly decreased lattice constant. Similar work published the next day by Si & Held[31] and Kurleto, et al.[91] | arXiv: Sinéad Griffin[30][b 1] Analysis:[92][93] |

| Universidad de Chile |  Chile Chile | DFT analysis, finding large electron-phonon coupling in the flat bands. | arXiv: J. Cabezas-Escares, et al.[94] |

| CIEMAT |  Spain, Spain,  Armenia Armenia | Concludes the original synthesis for LK-99 likely produces a heterogenous material, making it hard for others to reproduce the same results | arXiv: P. Abramian, et al.[22] |

| Northwest University (China) and TU Wien |  China, China,  Austria Austria | Concludes Pb9Cu(PO4)6O, without further doping, is an insulator. Analyzes possible effects of doping. | arXiv: Liang Si & Karsten Held[31][b 1] |

| Indiana University Bloomington |  United States United States | Concludes material is a transparent insulator, possibly with active Cu color centers at low temperature. Does not find signatures of type I or II superconductivity. Solves previous issues related to overestimation of lattice constant contraction, doping site energetics. Does not find flat bands at Fermi level, concluding they are related to an unfavored high-symmetry structure. | arxiv: A.B. Georgescu[95] Analysis and discussions:[96][97] |

See also

- Bismuth strontium calcium copper oxide: Superconductivity at Tc ≈ 33 K (−240.2 °C) to 104 K (−169 °C)

- Carbonaceous sulfur hydride: Purported superconductivity at Tc ≈ 288 K (15 °C) at 267 GPa

- Lanthanum decahydride: Superconductivity at Tc = 250 K (−23 °C) at 150 GPa

- Unconventional superconductor

- Salvatore Pais – Inventor with a patent referenced by a patent related to LK-99

References

Further reading

- 최동식 (17 May 1994). 초전도 혁명의 이론적 체계 [Theoretical Framework of the Superconducting Revolution] (in Korean). 고려대학교출판부. ISBN 89-7641-276-1. Archived from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- "최동식". Donga Science (Interview with T.S. Chair) (in Korean): 106‒107. September 1993. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- Krivovichev, Sergey V.; Burns, Peter C. (17 October 2002). "Crystal chemistry of lead oxide phosphates: crystal structures of Pb4O(PO4)2, Pb8O5(PO4)2 and Pb10(PO4)6O". Zeitschrift für Kristallographie – Crystalline Materials. 218 (5). Munich: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag (published 1 May 2003): 357–365. doi:10.1524/zkri.218.5.357.20732. S2CID 101229927.

The compound Pb10(PO4)6O has been designated 'oxypyromorphite' ... Pb10(PO4)6O crystallizes with an apatite-type structure. The structure contains a single O atom that is not part of a PO4 tetrahedron; it has a site occupancy factor of 0.25 and is located on the 63 axis.

- Lowe, Derek (26 July 2023). "Breaking Superconductor News". Chemical News. In the Pipeline (blog). American Association for the Advancement of Science. Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023 – via Science.org.

- Orf, Darren (27 July 2023). "Scientists Claim They Found the Holy Grail of Superconductors". Energy. Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- Harris, Margaret (27 July 2023). "Have scientists in Korea discovered the first room-temperature, ambient-pressure superconductor?". Superconductivity blog. Physics World. Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 28 July 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- Wu, Yuewei; Sun, Wenya; Li, Ruiyang (28 July 2023). 南大教授谈韩国室温超导:不像超导,正重复实验—新闻 [NU professor talks about room temperature superconductivity found in South Korea: Unlike superconductivity, experiments are being repeated]. ScienceNet.cn (broad overview) (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 31 July 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- 안경애 (8 August 2023). "'LK-99 샘플' 미세 결정구조 논문과 같다"...에너지공대 확인 [The 'LK-99' sample crystal structure matches published paper — [Korea University] College of Energy Engineering]. Digital Times (in Korean). Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

LK-99 연구에 참여하고 있는 한국에너지공대의 한 연구자는 8일 디지털타임스와의 통화에서 "샘플에 대한 X선 회절구조 분석 결과, 논문에 제시된 것과 샘플의 미세 결정구조가 같다는 사실을 확인했다"고 밝혔다. 이 연구자는 "미세 결정구조를 보면 물질의 물성을 확인하지 못해도 가능성을 추정할 수 있다. LK-99 분석을 위해 X레이로 미세 결정구조를 확인한 결과, 퀀텀에너지연구소 측이 논문에서 밝힌 결정구조와 샘플에서 확인되는 결정구조가 같았다"고 말했다.

- Shilin Zhu; Wei Wu; Zheng Li; Jianlin Luo (8 August 2023). "First-order transition in LK-99 containing Cu2S". Matter. 6 (12): 4401–4407. arXiv:2308.04353. doi:10.1016/j.matt.2023.11.001.

- Puphal, P.; Akbar, M. Y. P.; Hepting, M.; Goering, E.; Isobe, M.; Nugroho, A. A.; Keimer, B. (11 August 2023). "Single crystal synthesis, structure, and magnetism of Pb10− x Cu x (PO4)6O". APL Materials. 11 (10). arXiv:2308.06256. Bibcode:2023APLM...11j1128P. doi:10.1063/5.0172755. S2CID 260866146.

External links

- Magnetic Property Test of LK-99 Film (video). Quantum Energy Research Centre. 26 January 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2023 – via Youtube. This effect is a conductive copper plate induced by a magnetic.

- Kim, Hyun-Tak (25 July 2023). Superconductor Pb10-xCux(PO4)6O showing levitation at room temperature and atmospheric pressure and mechanism (video). Retrieved 25 July 2023 – via ScienceCast.

- List of replication claims, regularly updated:

- Compilation of Known Replication Attempt Claims. Guderian2nd, Spacebattles Forums. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- LK-99#Online Claims. Eiri Sanada. Retrieved 2 August 2023.