Modified gross national income (also Modified GNI or GNI*) is a metric used by the Central Statistics Office (Ireland) to measure the Irish economy rather than GNI or GDP. GNI* is GNI minus the depreciation on Intellectual Property, depreciation on leased aircraft and the net factor income of redomiciled PLCs.

While "Inflated GDP-per-capita" due to BEPS tools is a feature of tax havens,[1][2] Ireland was the first to adjust its GDP metrics. Economists, including Eurostat,[3] noted Irish Modified GNI (GNI*) is still distorted by Irish BEPS tools and US multinational tax planning activities in Ireland (e.g. contract manufacturing); and that Irish BEPS tools distort aggregate EU-28 data,[4] and the EU-US trade deficit.[5]

In August 2018, the Central Statistics Office (Ireland) (CSO) restated table of Irish GDP versus Modified GNI (2009–2017) showed GDP was 162% of GNI* (EU-28 2017 GDP was 100% of GNI).[6] Ireland's public § 2018 Debt metrics differ dramatically depending on whether Debt-to-GDP, Debt-to-GNI* or Debt-per-Capita is used.[7]

Original distortion

In February 1994, tax academic James R. Hines Jr., identified Ireland as one of seven major tax havens in his 1994 Hines-Rice paper,[10] still[as of?] the most cited paper in research on tax havens.[11] Hines noted that the profit shifting tools of US multinationals in corporate-focused tax havens distorted the national economic statistics of the haven as the scale of the profit shifting was disproportionate to haven's economy. An elevated GDP-per-capita became a "proxy indicator" of a tax haven.[2]

In November 2005, the Wall Street Journal reported that US technology and life sciences multinationals (e.g. Microsoft), were using an Irish base erosion and profit shifting ("BEPS") tool called the double Irish, to minimise their corporate taxes.[12][13] Designed by PwC (Ireland) tax partner, Feargal O'Rourke,[14][15] the double Irish would become the largest BEPS tool in history, and would enable US multinationals to accumulate over US$1 trillion in untaxed offshore profits.[16]

The accounting flows of BEPS tools can appear in national economic statistics, varying with each tool, but without contributing to the economy of the tax haven.[2]

Subsequent US Senate (2013), and EU Commission (2014–2016) investigations, into Apple's Irish tax structure, would show that starting in 2004, Apple's Irish subsidiary, Apple Sales International ("ASI"), would almost double the untaxed profits shifted through its double Irish BEPS tool every year, for a decade.[17]

| Year | ASI profit shifted (USD m) | Average €/$ rate | ASI profit shifted (EUR m) | Irish corp. tax rate | Irish corp. tax avoided (EUR m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 268 | .805 | 216 | 12.5% | 27 |

| 2005 | 725 | .804 | 583 | 12.5% | 73 |

| 2006 | 1,180 | .797 | 940 | 12.5% | 117 |

| 2007 | 1,844 | .731 | 1,347 | 12.5% | 168 |

| 2008 | 3,127 | .683 | 2,136 | 12.5% | 267 |

| 2009 | 4,003 | .719 | 2,878 | 12.5% | 360 |

| 2010 | 12,095 | .755 | 9,128 | 12.5% | 1,141 |

| 2011 | 21,855 | .719 | 15,709 | 12.5% | 1,964 |

| 2012 | 35,877 | .778 | 27,915 | 12.5% | 3,489 |

| 2013 | 32,099 | .753 | 24,176 | 12.5% | 3,022 |

| 2014 | 34,229 | .754 | 25,793 | 12.5% | 3,224 |

| Total | 147,304 | 110,821 | 13,853 |

From 2003 to 2007, research has shown that inflated Irish GDP from US multinational BEPS tools,[18] amplified the Irish Celtic Tiger period by stimulating Irish consumer optimism, who increased borrowing to OECD record levels; and global capital markets optimism about Ireland enabling Irish banks to borrow 180% of Irish deposits.[19]

This unwound in the economic crisis as global capital markets, who had ignored Ireland's deteriorating credit metrics and distorted GDP data when Irish GDP was rising, withdrew and precipitated an Irish property and banking collapse in 2009–2012.[18][20]

The 2009–2012 Irish economic collapse led to a transfer of indebtedness from the Irish private sector balance sheet, the most leveraged in the OECD with household debt-to-income at 190%, to the Irish public sector balance sheet, which was almost unleveraged pre-crisis. This was done via Irish bank bailouts and public deficit spending.[21][22]

2009 distortion restarts

During the Irish financial crisis from 2009 to 2012, two catalysts would restart the distortion of Irish economic statistics:

- The crisis caused the Irish State to look for new BEPS tools, and in September 2009, the Commission on Taxation,[24][25] recommended extending Irish capital allowances to intangible assets and intellectual property in particular; the "capital allowances for intangible assets" or "Green Jersey" BEPS tool, was created in the 2009 Finance Act; it would spur a new wave of US corporate tax inversions to Ireland;

- Irish-based US technology firms such as Apple and Google entered a stronger phase of growth; for example, in 2007, Apple's Irish ASI subsidiary was profit shifting just under USD 2 billion of untaxed global income through its hybrid-double Irish BEPS tool, however by 2012, ASI was profit shifting just under USD 36 billion of untaxed global income through Ireland, although only a small amount of this BEPS tool appeared in Irish GDP.[17]

In 2010, Hines published a new list of 52 global tax havens, the Hines 2010 list, which ranked Ireland as the 3rd largest tax haven in the world.[26]

By 2011, Eurostat showed that Ireland's ratio of GNI to GDP, had fallen to 80% (i.e. Irish GDP was 125% of Irish GNI, or artificially inflated by 25%). Only Luxembourg, who ranked 1st on Hines' 2010 list of global tax havens,[26] was lower at 73% (i.e. Luxembourg GDP was 137% of Luxembourg GNI). Eurostat's GNI/GDP table (see graphic) showed EU GDP is equal to EU GNI for almost every EU country, and for the aggregate EU-27 average.[18][27]

In 2013–2015 several large US life sciences multinationals executed tax inversions to Ireland (e.g. Medtronic). Ireland became the largest recipient of US corporate tax inversions in history.[28] The Irish BEPS tool enabled US multinationals to avoid almost all Irish corporate taxes, however, unlike other Irish BEPS tools, it registers fully in Irish economic statistics.[29] In April 2016, the Obama Administration blocked the proposed US$160 billion proposed Pfizer-Allergan Irish inversion.[30]

A 2015 EU Commission report into Ireland's economic statistics, showed that from 2010 to 2015, almost 23% of Ireland's GDP was now represented by untaxed multinational net royalty payments, thus implying that Irish GDP was now circa 130% of Irish GNI.[31] This analysis, however, did not capture the full effect of the BEPS tool as it uses capital allowances, rather than royalty payments, to execute the BEPS movement. The Irish media were also confused as to Ireland's state of indebtedness as Irish Debt-per-Capita diverged sharply from Irish Debt-to GDP.[32][33][34]

2016 distortion climax

By 2012–14, Apple's Irish subsidiary, ASI, was profit shifting circa US$35 billion per annum through Ireland, equivalent to 20% of Irish GDP, via its hybrid-double Irish BEPS tool.[17] However, this particular BEPS tool had a modest impact on Irish GDP data. In late 2014, to limit further exposure to fines from the EU Commission's investigation into Apple's Irish tax schemes, Apple closed its hybrid-double Irish BEPS tool,[35] and decided to swap into the BEPS tool.[36][37] In Q1 2015, Apple Ireland purchased circa US$300 billion of virtual IP assets owned by Apple Jersey, executing the largest BEPS action in history.[17][38]

The BEPS tool is recorded like a tax inversion in the Irish national accounts.[38] Because Apple's IP was now on-shored in Ireland, all of ASI's circa US$40 billion in profit shifting for 2015, appeared in 2015 Irish GDP and GNP, despite the fact that new BEPS tool would limit Apple's exposure to Irish corporation tax.

In July 2016, the Irish Central Statistice Office announced 2015 Irish economic growth rates of 26.3% (GDP) and 18.7% (GNP), as a result of Apple's restructuring.[39] The announcement led to ridicule,[40][41][42][43][44][45][46] and was labelled by Nobel Prize economist Paul Krugman as "leprechaun economics".[47]

From July 2016 to July 2018, the Central Statistics Office refused to identify the source of leprechaun economics, and suppressed the release of other economic data to protect Apple's identity under the 1993 Central Statistics Act,[48][49] in the manner of a "captured state", further damaging confidence in Ireland.[50]

By early 2017, research in the Sloan School of Management in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, using the limited data released by the Irish CSO, could conclude: While corporate inversions and aircraft leasing firms were credited for increasing Irish [2015] GDP, the impact may have been exaggerated.[51] The same research noted that capital markets did not consider Irish macro economic statistics to be credible or meaningful, as evidenced by the lack of any reaction by the capital markets to Ireland's 26.3% GDP growth (both on the day of release, and in the subsequent days).[51]

Where as the Obama Administration blocked the proposed US$160 billion Pfizer-Allergan Irish inversion in 2016, Apple's larger US$300 billion Irish inversion was ignored. It is not clear if this was due to the confusion caused by the Central Statistics Office (Ireland) in protecting Apple's identity for 2 years, or other reasons.

2017 GNI* response

In September 2016, as a direct result of the "leprechaun economics" affair, the Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland ("CBI"), Philip R. Lane, chaired a special cross-economic steering group, the Economic Statistics Review Group ("ESRG"), of stakeholders (incl. CBI, IFAC, ESRI, NTMA, leading academics and the Department of Finance), to recommend new economic statistics that would better represent the true position of the Irish economy.[52]

In February 2017, a new metric, "Modified Gross National Income" (or GNI* for short) was announced. The difference between GNI* and GNI is due to having to deal with two problems (a) The retained earnings of re-domiciled firms in Ireland (where the earnings ultimately accrue to foreign investors), and (b) depreciation on foreign-owned capital assets located in Ireland, such as intellectual property (which inflate the size of Irish GDP, but again the benefits accrue to foreign investors).[53][54]

The Central Statistics Office (Ireland) ("CSO") simplifies the definition of Irish modified GNI (or GNI*) as follows:

Irish GNI less the effects of the profits of re-domiciled companies and the depreciation of intellectual property products and aircraft leasing companies.[55]

In February 2017, the CSO stated they would continue to calculate and release Irish GDP and Irish GNP to meet their EU and other International statistical reporting commitments.[56] In July 2017, the CSO estimated that 2016 Irish GNI* (€190bn) was 30% below Irish GDP (€275bn), or that Irish GDP is 143% above Irish GNI*. The CSO also confirmed that Irish Net Public Debt-to-GNI* was 106% (Irish Net Public Debt-to-GDP, post leprechaun economics, was 73%).[57][58]

In December 2017, Eurostat noted that while GNI* was helpful, it was still being artificially inflated by BEPS flows, and the BEPS activities of certain types of contract manufacturing in particular;[3] a view shared by several others.[18][59][60][61][62][63] There have been several material revisions to Irish 2015 GDP in particular (as per § Irish GDP versus Modified GNI (2009–2017).[64] Modified GNI, or GNI*, was adopted by the IMF and OECD in their 2017 Ireland Country Reports.[65][66]

Economists noted in May 2018 that distorted Irish economic data was calling into question the credibility of Eurostat's aggregate EU-28 economic data.[4]

In June 2018, tax academic Gabriel Zucman, using 2015 economic data, claimed Irish BEPS tools had made Ireland the world's largest tax haven (Zucman-Tørsløv-Wier 2018 list).[67][68] Zucman also showed that Irish BEPS flows were becoming so large, that they were artificially exaggerating the scale of the EU-US trade deficit.[5]

Another study published in June 2018 by the IMF called into question the economic data of all leading tax havens, and the artificial effect of their BEPS tools.[1][69]

2018 debt metrics

The issues post leprechaun economics, and "modified GNI", are captured on page 34 of the OECD 2018 Ireland survey:[66]

- On a gross public debt-to-GDP basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 78.8% is not of concern;

- On a gross public debt-to-GNI* basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 116.5% is more serious, but not alarming;

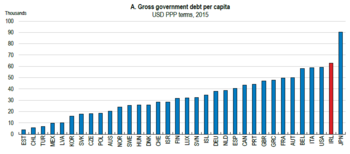

- On a gross public debt-per-capita basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at over $62,686 per capita, is the second highest in the OECD, after Japan.[71]

There is concern Ireland repeats the mistakes of the "Celtic Tiger" era, and over-leverages again, against distorted Irish economic data.[59] Given the transfer of Irish private sector debt to the Irish public balance sheet from the Irish 2009–2012 financial crisis, it will not be possible to bail out the Irish banking system again.

- In June 2017, the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council benchmarked Irish public debt against Irish tax revenues (similar to the debt-to-EBITDA ratio used in capital markets). Ireland's 2016 gross public debt-to-tax revenues was 282.9%, the 4th highest in the EU-28 (after Greece, Portugal, and Cyprus).[72][73][74]

- In November 2017, the Central Bank of Ireland benchmarked Irish private debt against Irish disposable income. Ireland's 2016 private debt as a % of Irish disposable income was 141.6%, the 4th highest in the EU-28 (after Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden).[75][76]

These two initiatives show Ireland's high public debt levels, and Ireland's high private sector debt levels, imply that on a "total debt" basis (i.e. Irish public debt plus Irish private debt), Ireland is likely one of the most indebted of the EU-27 countries when benchmarked on a GNI*-type basis; hence the importance of a GNI* metric.[citation needed]

Irish GDP versus Modified GNI (2009–2018)

| Year | Irish GDP | Irish GNI* | Irish GDP/GNI* ratio | EU-28 GDP/GNI ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (€ bn) | YOY (%) | (€ bn) | YOY (%) | |||

| 2009 | 170.1 | - | 134.8 | - | 126% | 100% |

| 2010 | 167.7 | -1.4% | 128.9 | -4.3% | 130% | 100% |

| 2011 | 171.1 | 2.0% | 126.6 | -1.8% | 135% | 100% |

| 2012 | 175.2 | 2.4% | 126.4 | -0.2% | 139% | 100% |

| 2013 | 179.9 | 2.7% | 136.9 | 8.3%‡ | 131% | 100% |

| 2014 | 195.3 | 8.6% | 148.3 | 8.3%‡ | 132% | 100% |

| 2015 | 262.5† | 34.4% | 161.4 | 8.8%‡ | 163% | 100% |

| 2016 | 273.2 | 4.1% | 175.8 | 8.9%‡ | 155% | 100% |

| 2017 | 294.1 | 7.6% | 181.2 | 3.1% | 162% | 100% |

| 2018^ | 324.0 | 8.2% | 197.5 | - | - | 100% |

(†) The Central Statistics Office (Ireland) revised 2015 GDP higher in 2017, increasing Ireland's "leprechaun economics" 2015 GDP growth rate from 26.3% to 34.4%.

(‡) Eurostat show that GNI* is also still distorted by certain BEPS tools, and specifically contract manufacturing, which is a significant activity in Ireland.[3]