Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene) is a stilbenoid, a type of natural phenol, and a phytoalexin produced by several plants in response to injury or when the plant is under attack by pathogens, such as bacteria or fungi.[6][7] Sources of resveratrol in food include the skin of grapes, blueberries, raspberries, mulberries, and peanuts.[8][9]

| |

| |

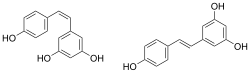

Chemical structures of cis- ((Z)-resveratrol, left) and trans-resveratrol ((E)-resveratrol, right)[1] | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name 5-[(E)-2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)ethen-1-yl]benzene-1,3-diol | |

| Other names trans-3,5,4′-Trihydroxystilbene; 3,4′,5-Stilbenetriol; trans-Resveratrol; (E)-5-(p-Hydroxystyryl)resorcinol; (E)-5-(4-hydroxystyryl)benzene-1,3-diol | |

| Identifiers | |

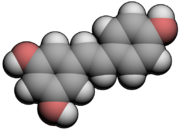

3D model (JSmol) | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.121.386 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID | |

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C14H12O3 | |

| Molar mass | 228.247 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white powder with slight yellow cast |

| Melting point | 261 to 263 °C (502 to 505 °F; 534 to 536 K)[2] |

| Solubility in water | 0.03 g/L |

| Solubility in DMSO | 16 g/L |

| Solubility in ethanol | 50 g/L |

| UV-vis (λmax) | 304nm (trans-resveratrol, in water) 286nm (cis-resveratrol, in water)[1] |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling:[5] | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H319 | |

| P264, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) | 23.2 μM (5.29 g)[4] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | Fisher Scientific[2] Sigma Aldrich[3] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

Although commonly used as a dietary supplement and studied in laboratory models of human diseases,[10] there is no high-quality evidence that resveratrol improves lifespan or has a substantial effect on any human disease.[11][12]

Research

Resveratrol has been studied for its potential therapeutic use,[13] with little evidence of anti-disease effects or health benefits in humans.[6][10][14]

Cardiovascular disease

There is no evidence of benefit from resveratrol in people who already have heart disease.[10][15] A 2018 meta-analysis found no effect on systolic or diastolic blood pressure; a sub-analysis revealed a 2 mmHg decrease in systolic pressure only from resveratrol doses of 300 mg per day, and only in diabetic people.[16] A 2014 Chinese meta-analysis found no effect on systolic or diastolic blood pressure; a sub-analysis found an 11.90 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure from resveratrol doses of 150 mg per day.[17]

Cancer

As of 2020[update], there is no evidence of an effect of resveratrol on cancer in humans.[10][18]

Metabolic syndrome

There is no conclusive evidence for an effect of resveratrol on human metabolic syndrome.[10][19][20] One 2015 review found little evidence for use of resveratrol to treat diabetes.[21] A 2015 meta-analysis found little evidence for an effect of resveratrol on diabetes biomarkers.[22]

One review found limited evidence that resveratrol lowered fasting plasma glucose in people with diabetes.[23] Two reviews indicated that resveratrol supplementation may reduce body weight and body mass index, but not fat mass or total blood cholesterol.[24][25] A 2018 review found that resveratrol supplementation may reduce biomarkers of inflammation, TNF-α and C-reactive protein.[26]

Lifespan

As of 2011[update], there is insufficient evidence to indicate that consuming resveratrol has an effect on human lifespan.[11]

Cognition

Resveratrol has been assessed for a possible effect on cognition, but with mixed evidence for an effect. One review concluded that resveratrol had no effect on neurological function, but reported that supplementation improved recognition and mood, although there were inconsistencies in study designs and results.[27]

Diabetes

Although animal experiments have found some evidence that resveratrol may help improve insulin sensitivity and so potentially help manage diabetes, subsequent research on people is limited and does not support the use of resveratrol for this purpose.[28]

Other

There is no significant evidence that resveratrol affects vascular endothelial function, neuroinflammation, Alzheimer's disease, skin infections or aging skin.[6][10] A 2019 review of human studies found mixed effects of resveratrol on certain bone biomarkers, such as increases in blood and bone alkaline phosphatase, while reporting no effect on other biomarkers, such as calcium and collagen.[29]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Resveratrol has been identified as a pan-assay interference compound, which produces positive results in many different laboratory assays.[30] Its ability for varied interactions may be due to direct effects on cell membranes.[31]

As of 2015, many specific biological targets for resveratrol had been identified, including NQO2 (alone and in interaction with AKT1), GSTP1, estrogen receptor beta, CBR1, and integrin αVβ. It was unclear at that time if any or all of these were responsible for the observed effects in cells and model organisms.[32]

Pharmacokinetics

The viability of an oral delivery method is unlikely due to the low aqueous solubility of the molecule. The bioavailability of resveratrol is about 0.5% due to extensive hepatic glucuronidation and sulfation.[33] Glucuronidation occurs in the intestine as well as in the liver, whereas sulfonation not only occurs in the liver but in the intestine and by microbial gut activity.[34] Due to rapid metabolism, the half-life of resveratrol is short (about 8–14 minutes), but the half-life of the sulphate and glucoronide metabolites is above 9 hours.[35]

Metabolism

Resveratrol is extensively metabolized in the body,[6] with the liver and intestines as the major sites of its metabolism.[36][35] Liver metabolites are products of phase II (conjugation) enzymes,[37] which are themselves induced by resveratrol in vitro.[38]

Chemistry

Resveratrol (3,5,4'-trihydroxystilbene) is a stilbenoid, a derivative of stilbene.[6] It exists as two geometric isomers: cis- (Z) and trans- (E), with the trans-isomer shown in the top image. Resveratrol exists conjugated to glucose.[39]

The trans- form can undergo photoisomerization to the cis- form when exposed to ultraviolet irradiation.[40][41]

UV irradiation to cis-resveratrol induces further photochemical reaction, producing a fluorescent molecule named "Resveratrone".[42]

Trans-resveratrol in the powder form was found to be stable under "accelerated stability" conditions of 75% humidity and 40 °C in the presence of air.[43] The trans isomer is also stabilized by the presence of transport proteins.[44] Resveratrol content also was stable in the skins of grapes and pomace taken after fermentation and stored for a long period.[45] lH- and 13C-NMR data for the four most common forms of resveratrols are reported in literature.[39]

Biosynthesis

Resveratrol is produced in plants via the enzyme resveratrol synthase (stilbene synthase).[46][47] Its immediate precursor is a tetraketide derived from malonyl CoA and 4-coumaroyl CoA.[46][47] The latter is derived from phenylalanine.[48]

Biotransformation

The grapevine fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea is able to oxidise resveratrol into metabolites showing attenuated antifungal activities. Those include the resveratrol dimers restrytisol A, B, and C, resveratrol trans-dehydrodimer, leachinol F, and pallidol.[49] The soil bacterium Bacillus cereus can be used to transform resveratrol into piceid (resveratrol 3-O-beta-D-glucoside).[50]

Adverse effects

Only a few human studies have been done to determine the adverse effects of resveratrol, all of them preliminary with small participant numbers. Adverse effects resulted mainly from long-term use (weeks or longer) and daily doses of 1000 mg or higher, causing nausea, stomach pain, flatulence, and diarrhea.[6] A review of 136 patients in seven studies who were given more than 500 mg for a month showed 25 cases of diarrhea, 8 cases of abdominal pain, 7 cases of nausea, and 5 cases of flatulence.[51] A 2018 review of resveratrol effects on blood pressure found that some people had increased frequency of bowel movements and loose stools.[16]

Occurrences

Plants

Resveratrol is a phytoalexin, a class of compounds produced by many plants when they are infected by pathogens or physically harmed by cutting, crushing, or ultraviolet radiation.[52]

Plants that synthesize resveratrol include knotweeds, pine trees including Scots pine and Eastern white pine, grape vines, raspberries, mulberries, peanut plants, cocoa bushes, and Vaccinium shrubs that produce berries, including blueberries, cranberries, and bilberries.[6][8][52]

Foods

The levels of resveratrol found in food varies considerably, even in the same food from season to season and batch to batch.[6]

Wine and grape juice

| Beverage | Resveratrol (μg/100 mL)[9] | |

|---|---|---|

| mean | range | |

| Red wine | 270 | 0 — 2780 |

| Rosé wine | 120 | 5 — 290 |

| White wine | 40 | 0 — 170 |

| Sparkling wine | 9 | 8 — 10 |

| Green grape juice | 5.08 | 0 — 10 |

Resveratrol concentrations in red wines average 1.9±1.7 mg trans-resveratrol/L (8.2±7.5 μM), ranging from nondetectable levels to 14.3 mg/L (62.7 μM) trans-resveratrol. Levels of cis-resveratrol follow the same trend as trans-resveratrol.[53]

In general, wines made from grapes of the Pinot noir and St. Laurent varieties showed the highest level of trans-resveratrol, though no wine or region can yet be said to produce wines with significantly higher concentrations than any other wine or region.[53] Champagne and vinegar also contain appreciable levels of resveratrol.[9]

Red wine contains between 0.2 and 5.8 mg/L, depending on the grape variety. White wine has much less because red wine is fermented with the skins, allowing the wine to extract the resveratrol, whereas white wine is fermented after the skin has been removed.[6] The composition of wine is different from that of grapes since the extraction of resveratrol from grapes depends on the duration of the skin contact, and the resveratrol 3-glucosides are in part hydrolysed, yielding both trans- and cis-resveratrol.[6][54]

Selected foods

| Food | Serving | Total resveratrol (mg)[6] |

|---|---|---|

| Peanuts (raw) | 1 cup (146 grams) | 0.01 – 0.26 |

| Peanut butter | 1 cup (258 grams) | 0.04 – 0.13 |

| Red grapes | 1 cup (160 grams) | 0.24 – 1.25 |

| Cocoa powder | 1 cup (200 grams) | 0.28 – 0.46 |

Ounce for ounce, peanuts have about 25% as much resveratrol as red wine.[6] Peanuts, especially sprouted peanuts, have a content similar to grapes in a range of 2.3 to 4.5 μg/g before sprouting, and after sprouting, in a range of 11.7 to 25.7 μg/g, depending on peanut cultivar.[9][52]

Mulberries (especially the skin) are a source of as much as 50 micrograms of resveratrol per gram dry weight.[55]

Most US supplements of resveratrol are derived from the root of Reynoutria japonica (also called Japanese knotweed, Hu Zhang, etc.)[6]

History

The first mention of resveratrol was in a Japanese article in 1939 by Michio Takaoka, who isolated it from Veratrum album, variety grandiflorum, and later, in 1963, from the roots of Japanese knotweed.[52][56][57][58] In 2004, Harvard University professor David Sinclair co-founded Sirtris Pharmaceuticals, the initial product of which was a resveratrol formulation.[59][60][61] Sirtris was purchased and made a subsidiary of GlaxoSmithKline in 2008 for $720 million and shut down in 2013, without successful drug development.[62][63]

Related compounds

- Dihydro-resveratrol

- Epsilon-viniferin, Pallidol and Quadrangularin A three different resveratrol dimers

- Elafibranor, a structurally related compound that acts as a dual PPARα/δ agonist

- THSG, a glycoside compound found in He Shou Wu which is very similar to resveratrol.

- Trans-diptoindonesin B, a resveratrol trimer

- Hopeaphenol, a resveratrol tetramer

- Oxyresveratrol, the aglycone of mulberroside A, a compound found in Morus alba, the white mulberry[64]

- Piceatannol, an active metabolite of resveratrol found in red wine

- Piceid, a resveratrol glucoside

- Pterostilbene, a doubly methylated resveratrol

- 4'-Methoxy-(E)-resveratrol 3-O-rutinoside, a compound found in the stem bark of Boswellia dalzielii[65]

- Rhaponticin a glucoside of the stilbenoid rhapontigenin, found in rhubarb rhizomes

See also

References

External links

Media related to Resveratrol at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Resveratrol at Wikimedia Commons