The reticular formation is a set of interconnected nuclei that are located in the brainstem, hypothalamus, and other regions. It is not anatomically well defined, because it includes neurons located in different parts of the brain. The neurons of the reticular formation make up a complex set of networks in the core of the brainstem that extend from the upper part of the midbrain to the lower part of the medulla oblongata.[2] The reticular formation includes ascending pathways to the cortex in the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) and descending pathways to the spinal cord via the reticulospinal tracts.[3][4][5][6]

| Reticular formation | |

|---|---|

| |

Traverse section of the medulla oblongata at about the middle of the olive. (Formatio reticularis grisea and formatio reticularis alba labeled at left.) | |

| Details | |

| Location | Brainstem, hypothalamus and other regions |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | formatio reticularis |

| MeSH | D012154 |

| NeuroNames | 1223 |

| NeuroLex ID | nlx_143558 |

| TA98 | A14.1.00.021 A14.1.05.403 A14.1.06.327 |

| TA2 | 5367 |

| FMA | 77719 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Neurons of the reticular formation, particularly those of the ascending reticular activating system, play a crucial role in maintaining behavioral arousal and consciousness. The overall functions of the reticular formation are modulatory and premotor,[A]involving somatic motor control, cardiovascular control, pain modulation, sleep and consciousness, and habituation.[7] The modulatory functions are primarily found in the rostral sector of the reticular formation and the premotor functions are localized in the neurons in more caudal regions.

The reticular formation is divided into three columns: raphe nuclei (median), gigantocellular reticular nuclei (medial zone), and parvocellular reticular nuclei (lateral zone). The raphe nuclei are the place of synthesis of the neurotransmitter serotonin, which plays an important role in mood regulation. The gigantocellular nuclei are involved in motor coordination. The parvocellular nuclei regulate exhalation.[8]

The reticular formation is essential for governing some of the basic functions of higher organisms and is one of the phylogenetically oldest portions of the brain.[citation needed]

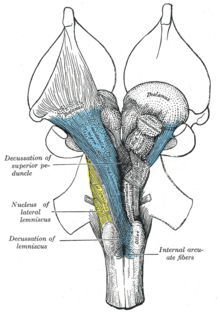

Structure

The human reticular formation is composed of almost 100 brain nuclei and contains many projections into the forebrain, brainstem, and cerebellum, among other regions.[3] It includes the reticular nuclei,[B]reticulothalamic projection fibers, diffuse thalamocortical projections, ascending cholinergic projections, descending non-cholinergic projections, and descending reticulospinal projections.[4] The reticular formation also contains two major neural subsystems, the ascending reticular activating system and descending reticulospinal tracts, which mediate distinct cognitive and physiological processes.[3][4] It has been functionally cleaved both sagittally and coronally.

Traditionally the reticular nuclei are divided into three columns:

- In the median column – the raphe nuclei

- In the medial column – gigantocellular nuclei (because of larger size of the cells)

- In the lateral column – parvocellular nuclei (because of smaller size of the cells)

The original functional differentiation was a division of caudal and rostral. This was based upon the observation that the lesioning of the rostral reticular formation induces a hypersomnia in the cat brain. In contrast, lesioning of the more caudal portion of the reticular formation produces insomnia in cats. This study has led to the idea that the caudal portion inhibits the rostral portion of the reticular formation.

Sagittal division reveals more morphological distinctions. The raphe nuclei form a ridge in the middle of the reticular formation, and, directly to its periphery, there is a division called the medial reticular formation. The medial RF is large and has long ascending and descending fibers, and is surrounded by the lateral reticular formation. The lateral RF is close to the motor nuclei of the cranial nerves, and mostly mediates their function.

Medial and lateral reticular formation

The medial reticular formation and lateral reticular formation are two columns of nuclei with ill-defined boundaries that send projections through the medulla and into the midbrain. The nuclei can be differentiated by function, cell type, and projections of efferent or afferent nerves. Moving caudally from the rostral midbrain, at the site of the rostral pons and the midbrain, the medial RF becomes less prominent, and the lateral RF becomes more prominent.[citation needed]

Existing on the sides of the medial reticular formation is its lateral cousin, which is particularly pronounced in the rostral medulla and caudal pons. Out from this area spring the cranial nerves, including the very important vagus nerve.[clarification needed] The lateral RF is known for its ganglions and areas of interneurons around the cranial nerves, which serve to mediate their characteristic reflexes and functions.

Function

The reticular formation consists of more than 100 small neural networks, with varied functions including the following:

- Somatic motor control – Some motor neurons send their axons to the reticular formation nuclei, giving rise to the reticulospinal tracts of the spinal cord. These tracts function in maintaining tone, balance, and posture – especially during body movements. The reticular formation also relays eye and ear signals to the cerebellum so that the cerebellum can integrate visual, auditory, and vestibular stimuli in motor coordination. Other motor nuclei include gaze centers, which enable the eyes to track and fixate objects, and central pattern generators, which produce rhythmic signals of breathing and swallowing.

- Cardiovascular control – The reticular formation includes the cardiac and vasomotor centers of the medulla oblongata.

- Pain modulation – The reticular formation is one means by which pain signals from the lower body reach the cerebral cortex. It is also the origin of the descending analgesic pathways. The nerve fibers in these pathways act in the spinal cord to block the transmission of some pain signals to the brain.

- Sleep and consciousness – The reticular formation has projections to the thalamus and cerebral cortex that allow it to exert some control over which sensory signals reach the cerebrum and come to our conscious attention. It plays a central role in states of consciousness like alertness and sleep. Injury to the reticular formation can result in irreversible coma.

- Habituation – This is a process in which the brain learns to ignore repetitive, meaningless stimuli while remaining sensitive to others. A good example of this is a person who can sleep through loud traffic in a large city, but is awakened promptly due to the sound of an alarm or crying baby. Reticular formation nuclei that modulate activity of the cerebral cortex are part of the ascending reticular activating system.[9][7]

Major subsystems

Ascending reticular activating system

The ascending reticular activating system (ARAS), also known as the extrathalamic control modulatory system or simply the reticular activating system (RAS), is a set of connected nuclei in the brains of vertebrates that is responsible for regulating wakefulness and sleep-wake transitions. The ARAS is a part of the reticular formation and is mostly composed of various nuclei in the thalamus and a number of dopaminergic, noradrenergic, serotonergic, histaminergic, cholinergic, and glutamatergic brain nuclei.[3][10][11][12]

Structure of the ARAS

The ARAS is composed of several neural circuits connecting the dorsal part of the posterior midbrain and anterior pons to the cerebral cortex via distinct pathways that project through the thalamus and hypothalamus.[3][11][12] The ARAS is a collection of different nuclei – more than 20 on each side in the upper brainstem, the pons, medulla, and posterior hypothalamus. The neurotransmitters that these neurons release include dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, histamine, acetylcholine, and glutamate.[3][10][11][12] They exert cortical influence through direct axonal projections and indirect projections through thalamic relays.[11][12][13]

The thalamic pathway consists primarily of cholinergic neurons in the pontine tegmentum, whereas the hypothalamic pathway is composed primarily of neurons that release monoamine neurotransmitters, namely dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, and histamine.[3][10] The glutamate-releasing neurons in the ARAS were identified much more recently relative to the monoaminergic and cholinergic nuclei;[14] the glutamatergic component of the ARAS includes one nucleus in the hypothalamus and various brainstem nuclei.[11][14][15] The orexin neurons of the lateral hypothalamus innervate every component of the ascending reticular activating system and coordinate activity within the entire system.[12][16][17]

| Nucleus type | Corresponding nuclei that mediate arousal | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Dopaminergic nuclei | [3][10][11][12] | |

| Noradrenergic nuclei |

| [3][10][12] |

| Serotonergic nuclei | [3][10][12] | |

| Histaminergic nuclei | [3][10][18] | |

| Cholinergic nuclei | [3][11][12][14] | |

| Glutamatergic nuclei |

| [11][12][14][15][18][19] |

| Thalamic nuclei | [3][11][20] |

The ARAS consists of evolutionarily ancient areas of the brain, which are crucial to the animal's survival and protected during adverse periods, such as during inhibitory periods of Totsellreflex, aka, "animal hypnosis".[C][22]The ascending reticular activating system which sends neuromodulatory projections to the cortex - mainly connects to the prefrontal cortex.[23] There seems to be low connectivity to the motor areas of the cortex.[23]

Functions of the ARAS

Consciousness

The ascending reticular activating system is an important enabling factor for the state of consciousness.[13] The ascending system is seen to contribute to wakefulness as characterised by cortical and behavioural arousal.[6]

Regulating sleep-wake transitions

The main function of the ARAS is to modify and potentiate thalamic and cortical function such that electroencephalogram (EEG) desynchronization ensues.[D][25][26] There are distinct differences in the brain's electrical activity during periods of wakefulness and sleep: Low voltage fast burst brain waves (EEG desynchronization) are associated with wakefulness and REM sleep (which are electrophysiologically similar); high voltage slow waves are found during non-REM sleep. Generally speaking, when thalamic relay neurons are in burst mode the EEG is synchronized and when they are in tonic mode it is desynchronized.[26] Stimulation of the ARAS produces EEG desynchronization by suppressing slow cortical waves (0.3–1 Hz), delta waves (1–4 Hz), and spindle wave oscillations (11–14 Hz) and by promoting gamma band (20–40 Hz) oscillations.[16]

The physiological change from a state of deep sleep to wakefulness is reversible and mediated by the ARAS.[27] The ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) of the hypothalamus inhibits the neural circuits responsible for the awake state, and VLPO activation contributes to the sleep onset.[28] During sleep, neurons in the ARAS will have a much lower firing rate; conversely, they will have a higher activity level during the waking state.[29] In order that the brain may sleep, there must be a reduction in ascending afferent activity reaching the cortex by suppression of the ARAS.[27]

Attention

The ARAS also helps mediate transitions from relaxed wakefulness to periods of high attention.[20] There is increased regional blood flow (presumably indicating an increased measure of neuronal activity) in the midbrain reticular formation (MRF) and thalamic intralaminar nuclei during tasks requiring increased alertness and attention.

Clinical significance of the ARAS

Mass lesions in brainstem ARAS nuclei can cause severe alterations in level of consciousness (e.g., coma).[30] Bilateral damage to the reticular formation of the midbrain may lead to coma or death.[31]

Direct electrical stimulation of the ARAS produces pain responses in cats and elicits verbal reports of pain in humans.[citation needed] Ascending reticular activation in cats can produce mydriasis,[32] which can result from prolonged pain. These results suggest some relationship between ARAS circuits and physiological pain pathways.[32]

Pathologies

Some pathologies of the ARAS may be attributed to age, as there appears to be a general decline in reactivity of the ARAS with advancing years.[33] Changes in electrical coupling[E] have been suggested to account for some changes in ARAS activity: if coupling were down-regulated, there would be a corresponding decrease in higher-frequency synchronization (gamma band). Conversely, up-regulated electrical coupling would increase synchronization of fast rhythms that could lead to increased arousal and REM sleep drive.[35] Specifically, disruption of the ARAS has been implicated in the following disorders:

- Narcolepsy: Lesions along the pedunculopontine (PPT/PPN) / laterodorsal tegmental (LDT) nuclei are associated with narcolepsy.[36] There is a significant down-regulation of PPN output and a loss of orexin peptides, promoting the excessive daytime sleepiness that is characteristic of this disorder.[16]

- Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) : Dysfunction of nitrous oxide signaling has been implicated in the development of PSP.[37]

- Parkinson's disease: REM sleep disturbances are common in Parkinson's. It is mainly a dopaminergic disease, but cholinergic nuclei are depleted as well. Degeneration in the ARAS begins early in the disease process.[36]

Developmental influences

There are several potential factors that may adversely influence the development of the ascending reticular activating system:

- Preterm birth:[38] Regardless of birth weight or weeks of gestation, premature birth induces persistent deleterious effects on pre-attentional (arousal and sleep-wake abnormalities), attentional (reaction time and sensory gating), and cortical mechanisms throughout development.

- Smoking during pregnancy:[39] Prenatal exposure to cigarette smoke is known to produce lasting arousal, attentional and cognitive deficits in humans. This exposure can induce up-regulation of α4β2 nicotinic receptors on cells of the pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN), resulting in increased tonic activity, resting membrane potential, and hyperpolarization-activated cation current. These major disturbances of the intrinsic membrane properties of PPN neurons result in increased levels of arousal and sensory gating, deficits (demonstrated by a diminished amount of habituation to repeated auditory stimuli). It is hypothesized that these physiological changes may intensify attentional dysregulation later in life.

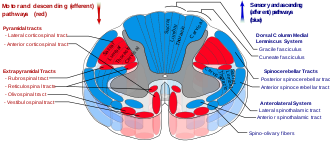

Descending reticulospinal tracts

The reticulospinal tracts, also known as the descending or anterior reticulospinal tracts, are extrapyramidal motor tracts that descend from the reticular formation[40] in two tracts to act on the motor neurons supplying the trunk and proximal limb flexors and extensors. The reticulospinal tracts are involved mainly in locomotion and postural control, although they do have other functions as well.[41] The descending reticulospinal tracts are one of four major cortical pathways to the spinal cord for musculoskeletal activity. The reticulospinal tracts work with the other three pathways to give a coordinated control of movement, including delicate manipulations.[40] The four pathways can be grouped into two main system pathways – a medial system and a lateral system. The medial system includes the reticulospinal pathway and the vestibulospinal pathway, and this system provides control of posture. The corticospinal and the rubrospinal tract pathways belong to the lateral system which provides fine control of movement.[40]

Medial and lateral tracts

This descending tract is divided into two parts, the medial (or pontine) and lateral (or medullary) reticulospinal tracts (MRST and LRST).

- The medial reticulospinal tract is responsible for exciting anti-gravity, extensor muscles. The fibers of this tract arise from the caudal pontine reticular nucleus and the oral pontine reticular nucleus and project to lamina VII and lamina VIII of the spinal cord.

- The lateral reticulospinal tract is responsible for inhibiting excitatory axial extensor muscles of movement. It is also responsible for automatic breathing. The fibers of this tract arise from the medullary reticular formation, mostly from the gigantocellular nucleus, and descend the length of the spinal cord in the anterior part of the lateral column. The tract terminates in lamina VII mostly with some fibers terminating in lamina IX of the spinal cord.

The ascending sensory tract conveying information in the opposite direction is known as the spinoreticular tract.

Functions of the reticulospinal tracts

- Integrates information from the motor systems to coordinate automatic movements of locomotion and posture

- Facilitates and inhibits voluntary movement; influences muscle tone

- Mediates autonomic functions

- Modulates pain impulses

- Influences blood flow to lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus.[42]

Clinical significance of the reticulospinal tracts

The reticulospinal tracts provide a pathway by which the hypothalamus can control sympathetic thoracolumbar outflow and parasympathetic sacral outflow.[citation needed]

Two major descending systems carrying signals from the brainstem and cerebellum to the spinal cord can trigger automatic postural response for balance and orientation: vestibulospinal tracts from the vestibular nuclei and reticulospinal tracts from the pons and medulla. Lesions of these tracts result in profound ataxia and postural instability.[43]

Physical or vascular damage to the brainstem disconnecting the red nucleus (midbrain) and the vestibular nuclei (pons) may cause decerebrate rigidity, which has the neurological sign of increased muscle tone and hyperactive stretch reflexes. Responding to a startling or painful stimulus, both arms and legs extend and turn internally. The cause is the tonic activity of lateral vestibulospinal and reticulospinal tracts stimulating extensor motoneurons without the inhibitions from rubrospinal tract.[44]

Brainstem damage above the red nucleus level may cause decorticate rigidity. Responding to a startling or painful stimulus, the arms flex and the legs extend. The cause is the red nucleus, via the rubrospinal tract, counteracting the extensor motorneuron's excitation from the lateral vestibulospinal and reticulospinal tracts. Because the rubrospinal tract only extends to the cervical spinal cord, it mostly acts on the arms by exciting the flexor muscles and inhibiting the extensors, rather than the legs.[44]

Damage to the medulla below the vestibular nuclei may cause flaccid paralysis, hypotonia, loss of respiratory drive, and quadriplegia. There are no reflexes resembling early stages of spinal shock because of complete loss of activity in the motorneurons, as there is no longer any tonic activity arising from the lateral vestibulospinal and reticulospinal tracts.[44]

History

The term "reticular formation" was coined in the late 19th century by Otto Deiters, coinciding with Ramon y Cajal's neuron doctrine. Allan Hobson states in his book The Reticular Formation Revisited that the name is an etymological vestige from the fallen era of the aggregate field theory in the neural sciences. The term "reticulum" means "netlike structure", which is what the reticular formation resembles at first glance. It has been described as being either too complex to study or an undifferentiated part of the brain with no organization at all. Eric Kandel describes the reticular formation as being organized in a similar manner to the intermediate gray matter of the spinal cord. This chaotic, loose, and intricate form of organization is what has turned off many researchers from looking farther into this particular area of the brain.[citation needed] The cells lack clear ganglionic boundaries, but do have clear functional organization and distinct cell types. The term "reticular formation" is seldom used anymore except to speak in generalities. Modern scientists usually refer to the individual nuclei that compose the reticular formation.[citation needed]

Moruzzi and Magoun first investigated the neural components regulating the brain's sleep-wake mechanisms in 1949. Physiologists had proposed that some structure deep within the brain controlled mental wakefulness and alertness.[25] It had been thought that wakefulness depended only on the direct reception of afferent (sensory) stimuli at the cerebral cortex.

As direct electrical stimulation of the brain could simulate electrocortical relays, Magoun used this principle to demonstrate, on two separate areas of the brainstem of a cat, how to produce wakefulness from sleep. He first stimulated the ascending somatic and auditory paths; second, a series of "ascending relays from the reticular formation of the lower brain stem through the midbrain tegmentum, subthalamus and hypothalamus to the internal capsule."[45] The latter was of particular interest, as this series of relays did not correspond to any known anatomical pathways for the wakefulness signal transduction and was coined the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS).

Next, the significance of this newly identified relay system was evaluated by placing lesions in the medial and lateral portions of the front of the midbrain. Cats with mesencephalic interruptions to the ARAS entered into a deep sleep and displayed corresponding brain waves. In alternative fashion, cats with similarly placed interruptions to ascending auditory and somatic pathways exhibited normal sleeping and wakefulness, and could be awakened with physical stimuli. Because these external stimuli would be blocked on their way to the cortex by the interruptions, this indicated that the ascending transmission must travel through the newly discovered ARAS.

Finally, Magoun recorded potentials within the medial portion of the brain stem and discovered that auditory stimuli directly fired portions of the reticular activating system. Furthermore, single-shock stimulation of the sciatic nerve also activated the medial reticular formation, hypothalamus, and thalamus. Excitation of the ARAS did not depend on further signal propagation through the cerebellar circuits, as the same results were obtained following decerebellation and decortication. The researchers proposed that a column of cells surrounding the midbrain reticular formation received input from all the ascending tracts of the brain stem and relayed these afferents to the cortex and therefore regulated wakefulness.[45][27]

See also

Footnotes

References

Other references

- Systems of The Body (2010)

- Michael-Titus, Adina T; Revest, Patricia; Shortland, Peter, eds. (2010a). "Chapter 6 – Cranial Nerves and the Brainstem". Systems of The Body: The Nervous System – Basic Science and Clinical Conditions (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0702033735.

- Michael-Titus, Adina T; Revest, Patricia; Shortland, Peter, eds. (2010b). "Chapter 9 – Descending Pathways and Cerebellum". Systems of The Body: The Nervous System – Basic Science and Clinical Conditions (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0702033735.

- Neuroscience (2018)

- Purves, Dale; Augustine, George J; Fitzpatrick, David; Hall, William C; Lamantia, Anthony Samuel; Mooney, Richard D; Platt, Michael L; White, Leonard E, eds. (2018b). "Chapter 28 – Cortical State". Neuroscience (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-1605353807.

- Anatomy and Physiology (2018)

- Saladin, KS (2018a). "Chapter 13 – The Spinal Cord, Spinal Nerves, and Somatic Reflexes". Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1259277726.

- Saladin, KS (2018b). "Chapter 14 – The Brain and Cranial Nerves". Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. The Reticular Formation, pp. 518–519. ISBN 978-1259277726.

External links

The dictionary definition of reticular formation at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of reticular formation at Wiktionary