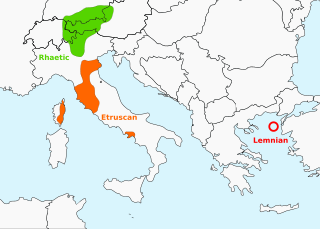

Rhaetic or Raetic (/ˈriːtɪk/), also known as Rhaetian,[2] was a Tyrsenian language spoken in the ancient region of Rhaetia in the eastern Alps in pre-Roman and Roman times. It is documented by around 280 texts dated from the 5th up until the 1st century BC, which were found through northern Italy, southern Germany, eastern Switzerland, Slovenia and western Austria,[3][4] in two variants of the Old Italic scripts.[5] Rhaetic is largely accepted as being closely related to Etruscan.[6]

| Rhaetic | |

|---|---|

| Raetic | |

| Native to | Ancient Rhaetia |

| Region | Eastern Alps, Italy, Austria, Switzerland, Germany, Slovenia[1] |

Tyrsenian

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xrr |

xrr | |

| Glottolog | raet1238 |

| |

The ancient Rhaetic language is not to be confused with the modern Romance languages of the same Alpine region, known as Rhaeto-Romance.

Classification

The German linguist Helmut Rix proposed in 1998 that Rhaetic, along with Etruscan, was a member of a language family he called Tyrrhenian, and which was possibly influenced by neighboring Indo-European languages.[8][9] Robert S. P. Beekes likewise does not consider it Indo-European.[10] Howard Hayes Scullard (1967), on the contrary, suggested it to be an Indo-European language, with links to Illyrian and Celtic.[11] Nevertheless, most scholars now think that Rhaetic is closely related to Etruscan within the Tyrrhenian grouping.[12]

Rix's Tyrsenian family is supported by a number of linguists such as Stefan Schumacher,[13][14] Carlo De Simone,[15] Norbert Oettinger,[16] Simona Marchesini,[7] and Rex E. Wallace.[17] Common features between Etruscan, Rhaetic, and Lemnian have been observed in morphology, phonology, and syntax. On the other hand, few lexical correspondences are documented, at least partly due to the scanty number of Rhaetic and Lemnian texts and possibly to the early date at which the languages split.[18][19] The Tyrsenian family (or Common Tyrrhenic) is often considered to be Paleo-European and to predate the arrival of Indo-European languages in southern Europe.[20][21][22]

History

In 2004 L. Bouke van der Meer proposed that Rhaetic could have developed from Etruscan from around 900 BC or even earlier, and no later than 700 BC, since divergences are already present in the oldest Etruscan and Rhaetic inscriptions, such as in the grammatical voices of past tenses or in the endings of male gentilicia. Around 600 BC, the Rhaeti became isolated from the Etruscan area, probably by the Celts, thus limiting contacts between the two languages.[12] Such a late datation has not enjoyed consensus, because the split would still be too recent, and in contrast with the archaeological data, the Rhaeti in the second Iron Age being characterized by the Fritzens-Sanzeno culture, in continuity with late Bronze Age culture and early Iron Age Laugen-Melaun culture. The Raeti are not believed, archeologically, to descend from the Etruscans, as well as it is not believed plausible that the Etruscans are descended from the Rhaeti.[23] Helmut Rix dated the end of the Proto-Tyrsenian period to the last quarter of the 2nd millennium BC.[24] Carlo De Simone and Simona Marchesini have proposed a much earlier date, placing the Tyrsenian language split before the Bronze Age.[25][26] This would provide one explanation for the low number of lexical correspondences.[27]

The language is documented in Northern Italy between the 5th and the 1st centuries BC by about 280 texts, in an area corresponding to the Fritzens-Sanzeno and Magrè cultures.[4] It is clear that in the centuries leading up to Roman imperial times, the Rhaetians had at least come under Etruscan influence, as the Rhaetic inscriptions are written in what appears to be a northern variant of the Etruscan alphabet. The ancient Roman sources mention the Rhaetic people as being reputedly of Etruscan origin, so there may at least have been some ethnic Etruscans who had settled in the region by that time.[citation needed]

In his Natural History (1st century AD), Pliny wrote about Alpine peoples:

... adjoining these (the Noricans) are the Rhaeti and Vindelici. All are divided into several states.[a] The Rhaeti are believed to be people of Etruscan race[b] driven out by the Gauls; their leader was named Rhaetus.[28]

Pliny's comment on a leader named Rhaetus is typical of mythologized origins of ancient peoples, and not necessarily reliable. The name of the Venetic goddess Reitia has commonly been discerned in the Rhaetic finds, but the two names do not seem to be linked. The spelling as Raet- is found in inscriptions, while Rhaet- was used in Roman manuscripts; it is unclear whether this Rh represents an accurate transcription of an aspirated R in Rhaetic, or is merely an error.[citation needed]

Phonology

Our understanding of Rhaetic phonology is quite uncertain, and the working hypothesis is that it's very similar to Etruscan phonology.[29]

Vowels

It appears that Rhaetic, like Etruscan, had a four-vowel system: /a/, /i/, /e/, /u/.

Consonants

Unlike Etruscan, Rhaetic does not seem to have the distinction between aspirated and non-aspirated stops. Consonant phonemes attested in Rhaetic include a dental (or palatal) affricate /ts/, dental sibilant /s/, palatal sibilant /ś/, nasals /n/, /m/ and liquids /r/, /l/.

Morphology

Nouns

The following cases are attested in Rhaetic:[30]

- Nominative/Accusative: No ending

- Genitive: Ending -s

- Pertinentive (locative to the genitive): Endings -si and -(a-)le

- Locative: Ending -i (uncertainly attested)

- Ablative: Ending -s

For plural, the ending -r(a) is attested.

Verbs

Two verbal suffixes have been identified, both known from Etruscan:

See also

Notes

References

Sources

Further reading

- A. Baruffi, Spirit of Rhaetia: The Call of the Holy Mountains (LiteraryJoint, Philadelphia, PA, 2020), ISBN 978-1-716-30027-1

- Salomon, Corinna (2017). Raetic: Language, Writing, Epigraphy. Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza. ISBN 978-84-16935-03-1.

- Salomon, Corinna (2020). "Raetic". Palaeohispanica. Revista sobre lenguas y culturas de la Hispania Antigua (20): 263–298. doi:10.36707/palaeohispanica.v0i20.380. ISSN 1578-5386.

External links

- Schumacher, Stefan; Kluge, Sindy (2013–2017). Salomon, Corinna (ed.). "Thesaurus Inscriptionum Raeticarum". Department of Linguistics. of the University of Vienna.

- Zavaroni, Adolfo, Rhaetic inscriptions, Tripod.