Tran Ngoc Châu (1 January 1924 – 17 June 2020) was a Vietnamese soldier (Lieutenant Colonel), civil administrator (city mayor, province chief), politician (leader of the Lower House of the National Assembly), and later political prisoner, in the Republic of Vietnam until its demise with the Fall of Saigon in 1975.

Trần Ngọc Châu | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1968 | |

| Member of the House of Representatives of South Vietnam | |

| In office 31 October 1967 – 27 February 1970 Serving with Lê Quang Hiền | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by |

|

| Constituency | Kiến Hòa Province |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 January 1924 Huế, Annam, French Indochina |

| Died | 17 June 2020 (aged 96) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Spouse | Hồ Thị Bích-Nhan |

| Children | 7 |

| Alma mater | Dalat Military Academy |

Much earlier in 1944, he had joined the Việt Minh to fight for independence from the French. Yet as a Vietnamese Buddhist by 1949 he had decisively turned against Communism in Vietnam. He then joined new nationalist forces led by the French. When Vietnam was divided in 1954, he became an officer in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN).

For many years he worked on assignments directly under President Ngô Đình Diệm (1954–1963). He became the mayor of Da Nang, and was later a province chief in the Mekong Delta. In particular, Châu became known for his innovative approaches to the theory and practice of counter-insurgency: the provision of security ("pacification") to civilian populations during the Vietnam War. The ultimate government goal of winning the hearts and minds of the people eventually led him to enter politics.

In 1967, after resigning from the ARVN Châu was elected to the newly formed National Assembly in Saigon. He became a legislative leader. Along with others, however, he failed to persuade his old friend Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, the former general who had become President (1967–1975), to turn toward a negotiated peace. Hence Châu associated with Assembly groups in opposition to the prevailing war policies and the ubiquitous corruption.

Under the pretext that he spoke to his communist brother, Châu was accused of treason in 1970, during a major government crackdown on dissidents. Among others, Daniel Ellsberg spoke on his behalf before the United States Congress. Amid sharp controversy in South Vietnam, widely reported in the international press, Châu was tried and sent to prison for several years. Detention under house arrest followed. Soon after Saigon fell in 1975, he was arrested and held by the new communist regime, in a re-education camp. Released in 1978, he and his family made their escape by boat, eventually arriving in America in 1979.[1]

Early life and career

Family, education

Tran Ngoc Châu was born in 1923 or 1924 into a Confucian–Buddhist family of government officials (historically called mandarins, quan in Vietnamese),[2][3] who lived in the ancient city of Huế, then the imperial capital, on the coast of central Vietnam. Since birth records at that time were not common, his family designated January 1, 1924, as his birthday "just for convenience".[4] His grandfather Tran Tram was a well-known scholar and a minister in the imperial cabinet, and his father Tran Dao Te was a chief judge.[5] As traditional members of the government, his family had "never resigned themselves to French rule." Châu spent seven youthful years as a student monk at a Buddhist school and seminary. In addition he received a French education at a lycée. Yet along with his brothers and sister, and following respected leaders, Châu became filled with "the Vietnamese nationalist spirit" and determined to fight for his country's independence.[6][7][8]

In the Việt Minh resistance

In 1944, Châu joined the anti-French and anti-Japanese "resistance" (khang chien), that is, the Việt Minh. He followed two older brothers and a sister.[9][10][11] Then considered a popular patriotic organization, the Việt Minh emphasized Vietnamese nationalism.[12][13][14] Châu was picked to attend a 3-month "Political Military Course". Afterwards he was made a platoon leader.[15]

Here Châu mixed with peasants and workers for the first time, experiencing "the great gap between the privileged... and the underprivileged" and the "vital role" played by the rural villagers in Vietnam's destiny. He participated in the rigors of Việt Minh indoctrination, the "critiquing sessions" and party discipline, and admired the dedication of Vietnamese patriots. Exemplary was his young immediate superior Ho Ba, also from a mandarin family. Châu lived the rough life as a guerrilla soldier, entering combat many times. Yet he saw what he thought a senseless execution of a young woman justified as "revolutionary brutality". He also saw evidence of similar harsh behavior by French colonial forces. Châu was selected to head a company (over a hundred soldiers) and led his compatriots into battle. Promoted then to "battalion political commissar", Ho Ba had asked him to join the Communist Party of Vietnam.[16][17][18]

A year after Châu had entered the rural Việt Minh, Japan surrendered ending World War II. Up north Việt Minh armed forces seized control of Hanoi in the August Revolution. Ho Chi Minh (1890–1969) proclaimed Vietnamese independence, and became the first President.[19][20] The French, however, soon returned and war commenced anew. Several writers comment that in 1945 Ho Chi Minh had become indelibly identified with Vietnamese independence, conferring on him the Mandate of Heaven in the eyes of many Vietnamese, and that his ultimate victory against France and later America predictably followed.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29]

Châu's promotion to battalion political officer[30] caused him to reflect on his path "from the contemplative life of a Buddhist monastery to the brutal reality of war". The Việt Minh depended on popular support, which the political commissar facilitated and propagated. In that position, Châu was called upon to show his "personal conviction" in the war and in the "social revolution", and to inspire the goodwill of the people. "It was equally vital that the political commissar be able to impart that conviction", to set "a high standard for others to emulate". To do so, Châu says, was like "converting to a new religion". About Việt Minh ideology and practices, his Buddhist convictions were divided: he favored "social justice, compassion, and liberation of the individual" but he opposed the "cultivated brutality" and "obsessive hatred" of the enemy, and the condemnation of "an entire social class". Châu found himself thinking that communist leaders from the mandarin class were using their peasant recruits to attack mandarin political rivals. "President Ho and General Giáp ... came from the very classes" that communist indoctrination was teaching the cadres to hate.[31][32][33] Yet Châu's duties, e.g., in "critiques and self-criticism sessions" and fighting the guerrilla war, left him little time for "personal philosophizing". When asked to join the party, Châu realized that, like most Vietnamese people in the Việt Minh, "I really knew little about communism."[34]

After four years spent mostly in the countryside and forest; the soldier Châu, eventually came to a state of disagreement with the resistance leadership when he learned of its half-hidden politics, and what he took to be the communist vision for Vietnam's future. Although the Việt Minh was then widely considered to represent a popular nationalism, Châu objected to its core communist ideology which rejected many Vietnamese customs, traditional family ties, and the Buddhist religion.[35][36] He quit the Việt Minh in 1949. Although remaining a nationalist in favor of step-by-step independence, he severed his ties, and began his outright opposition to communism.[37][38] "I realized my devotion to Buddhism distanced me from Communist ideology", Châu wrote decades later in his memoirs.[39][40][41][42]

In the army of Bảo Đại

Yet his new situation "between the lines of war" was precarious; it could prove to be fatal if he was captured by either the French or the Việt Minh.[44][45] Soon Châu, unarmed, wearing khakis and a Việt Minh fatigue cap, carefully approached Hội An provincial headquarters in French-controlled Vietnam and cried, "I'm a Việt Minh officer and I want to talk". He was interrogated by civil administrators, Sûreté, and the military, both French nationals and Vietnamese. Later Châu shared his traditional nationalism with an elder Vietnamese leader, Governor Phan Van Giao, whose strategy was to outlast the French and then reconcile with the Việt Minh.[46] At a café he recognized the young waitress as a former, or current, Việt Minh. Châu's Buddhist father, Tran Dao Te, suggested he seek religious guidance through prayer and meditation to aid him in his decision making. Two brothers, and a sister with her husband remained Việt Minh; yet Châu came to confirm his traditional nationalism, and his career as a soldier.[47]

I had quit the Việt Minh because I wanted independence for my country, but not with its traditional society and roots totally destroyed, which was the Communists' goal. I wanted to preserve the value of our culture and my religion, to see peace and social justice for everyone, but without unnecessary class struggle.[48][49]

In 1950, Châu entered the Dalat military academy established by the French to train officers for the Vietnamese National Army, nominally under the emperor Bảo Đại. By then the US, Britain, and Thailand recognized Vietnam's 'independence'. Graduating as a lieutenant he was assigned to teach at the academy. Châu then married Bich Nhan whom he had met in Huế. The couple shared a villa and became friends with another young army couple, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu and his wife. Thiệu also had served in the Việt Minh, during 1945–46, before crossing over to the other side.[50] In 1953 Châu traveled to Hanoi (Vietnam being not yet divided) for advanced military study. On his next assignment near Hội An his battalion was surprised by a Việt Minh ambush. His unit's survival was in doubt. For his conduct in battle Châu was awarded the highest medal. He was also promoted to captain. Following French defeat in 1954, full independence, and partition of Vietnam into north and south, Châu served in the military of the southern government, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN).[51][52][53][54]

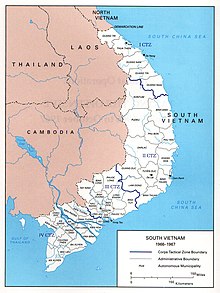

Division of the country resulted in massive population shifts, with most Việt Minh soldiers and cadre (90,000) heading north,[55] and some Buddhists (300,000) and many Catholics (800,000) heading south.[56][57][58][59] The Việt Minh remnant and 'stay behinds' in the south used "armed propanganda" to recruit new followers.[60][61] Eventually they formed the National Liberation Front (NLF), which soon came to be known as the Viet Cong (VC). It fought against the Republic of Vietnam (capital: Saigon), in a continuation of its national struggle for communist revolution and control. By 1960 use of armed violence became the practical policy of the communist party that dominated the NLF, both supported by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in Hanoi.[62][63][64]

Service in the Diệm regime

During the transition from French rule to full independence Ngô Đình Diệm,[65] the President of the Republic, although making costly mistakes managed to lead the southern state through a precarious stage in the establishment of its sovereignty.[66] Meanwhile, Châu in 1955 became commandant of cadets, director of instruction, at his alma mater the Vietnamese military academy at Dalat. He recommended curriculum changes, e.g., inclusion of Vietnamese history and guerrilla warfare, yet the American advisor resisted. For a time he also ran afoul of the secretive Cần Lao political party, a major support of the Diệm regime.[67][68] The American military sponsored special training at Fort Benning, Georgia, for a group of Vietnamese Army officers including Châu. Later, after transferring from the Fourth Infantry Division, he became chief of staff at Quang Trung National Training Center, a large Vietnamese Army facility. There Châu discovered corruption among suppliers.[69][70][71]

In 1959, at the request of his commanding officer, Châu prepared a report for the president's eyes. Unexpectedly, President Diệm then scheduled a meeting with Châu ostensibly to discuss his well-prepared report. Instead Diệm spoke at length of his high regard for Châu's mandarin grandfather the state minister Tran Tram, for his father and his accomplished family in Huế, the former Vietnamese capital.[72][73] The President, himself of a mandarin family, cultivated a formal Confucian style.[74][75][76] In contrast, Ho Chi Minh, also from a mandarin family, preferred instead a villager identity, being popularly known as "Uncle Ho" [Bac Ho in Vietnamese].[77][78][79][80]

The time-honored Confucian philosophy[81] behind the traditional mandarin ethic, remains in Vietnamese culture and elsewhere.[82] Yet it had been challenged in East Asia, methodically and decisively, since the arrival of western culture.[83][84][85] The revolutionary Chinese Communist Party had vilified it.[86][87][88] Modified teachings of the ancient sage continue, however, and across East Asia Confucian influence has increased markedly during the 21st century.[89][90][91][92]

For Diệm and Châu, its values served as a major reference held in common.[93]

Investigating the Civil Guard

Soon after Diệm assigned Châu to the Civil Guard and Self-Defense Corps as inspector for 'psychological and social conditions'. Following Diệm's instructions Châu investigated the Guard's interaction with the people and its military effectiveness.[94] Diệm had told Châu that his job was extremely important as the popular reputation of the Civil Guard in the countryside largely influenced how most people thought about the entire military.[95][96]

The Civil Guard (Bao An) was ineffective, poorly paid and poorly trained. Moreover, they preyed on the peasants whom they were supposed to protect. The Guard's political superiors, the provincial and local officials, were "holdovers from the French". To them, anyone who had participated in the independence struggle against France was suspected of being Viet Cong. Châu recommended general reforms: elimination of bribery and corruption, land reform, education, and the cultivation of a nationalist spirit among the people. Châu noted that the Americans aided only the military, ignoring the Civil Guard despite its daily contact with rural people and the Viet Cong.[97][98]

Diệm instructed Châu to develop a "refresher course" for the Guard. In doing so Châu addressed such content as: increased motivation, efforts to "earn the trust" of the people, better intelligence gathering, "interactive self-critical sessions", and the protection of civilians. Thereafter, Diệm appointed Châu as a regional commander of the Civil Guard for seven provinces of the Mekong Delta. American officials, military and CIA, began to show interest in Châu's work.[99] Journalist Grant writes that in the Mekong "Châu's job was to set an example that could be followed throughout the country."[100] Yet despite the efforts made, Châu sensed that a "great opportunity" was being missed: to build a national élan among the country people of South Vietnam that would supplant the vapid air of the French holdovers, and to reach out to former Việt Minh in order to rally them to the government's side.[101][102][103][104]

Following up on Châu's Civil Guard experience, Diệm sent him to troubled Malaysia to study the pacification programs there. Among other things, Châu found that, in contrast to Vietnam, in Malaysia (a) civilian officials controlled pacification rather than the military, (b) when arresting quasi-guerrillas certain legal procedures were followed, and (c) government broadcasts were more often true than not. When he returned to Saigon during 1962, his personal meeting with the president lasted a whole day. Yet a subsequent meeting with the president's brother Ngô Đình Nhu disappointed Châu's hopes. Then Diệm appointed Châu the provincial governor of Kiến Hòa in the Mekong Delta. Châu objected that as a military officer he was not suited to be a civil administrator, but Diệm insisted.[105][106]

Đà Nẵng: Buddhist crisis

In the meantime, the Diệm regime in early 1963 issued an order banning display of all non-state flags throughout South Vietnam. By its timing the order would first apply to the Buddhist flag during the celebration of Buddha's Birthday (Le Phát Dan) in May. Châu and many Buddhists were "outraged" and he called the President's office. Diệm's family was Catholic. Châu held not Diệm himself, but his influential brothers, responsible for the regime's "oppressive policies toward Buddhists".[107][108][109] The next morning a small plane arrived in Kiến Hòa Province to take Châu to Saigon to meet with Diệm. After discussion, Diệm in effect gave Châu complete discretion as province chief in Kiến Hòa. But soon in Huế, violence erupted: nine Buddhists were killed. Then "fiery suicides" by Buddhist monks made headlines and stirred the Vietnamese.[110][111]

Diệm then quite abruptly appointed Châu mayor of the large city of Đà Nẵng near Huế. At the time Da Nang had also entered a severe civil crisis involving an intense, local conflict between Buddhists and Catholics. These emergencies were a seminal part of what became the nationwide Buddhist crisis. From Diệm's instructions, Châu understood that as mayor he would have "complete authority to do what [he] thought was right". During the troubles in Da Nang, Châu met with Diệm in Saigon nearly every week.[112][113][114][115][116][117]

Arriving in Da Nang, Châu consulted separately first with the Buddhist monks, and then later with units of the army stationed in Da Nang (most of whose soldiers Châu describes as Catholics originally from northern Vietnam[118] and anti-Buddhist). A Buddhist elder who arrived from Huế endorsed Châu to his co-religionists as a loyal Buddhist. As Da Nang mayor he ordered the release of Buddhists held in detention by the army. When an army colonel refused to obey Châu, he called Diệm who quickly replaced the rebellious colonel. "The city returned to near-normal."[119]

Yet that August, instigated by Diệm's brother Nhu, armed forces of the Saigon regime conducted the pagoda raids throughout Vietnam, which left many Buddhist monks in jail.[120][121] In Da Nang, Châu rescued an elderly monk from police custody. Then Châu met with hostile Buddhists in a "stormy session". The Buddhist wanted to stage a large demonstration in Da Nang, to which Châu agreed, but he got a fixed route, security, and assurances. During the parade, however, the Catholic Cathedral in Da Nang was stoned. Châu met with protesting Vietnamese Catholics, especially with Father An. He reminded them that "Diệm, a devout Catholic" had appointed him mayor of Da Nang. Accordingly, it was his duty to "be fair to everyone" and to favor no one. "Passions subsided gradually on all sides, and relative calm returned to the city" of Da Nang by late October.[122][123]

A few days later Châu heard fresh rumors of a military plot against Diệm.[124] Senior elements in the military, encouraged by the American embassy (yet American support vacillated), had been meeting. They began to plan the 1963 coup d'état, which occurred on November 1.[125][126]

Diệm's fall, aftermath

When Châu arrived at the Saigon airport from Da Nang for another routine meeting with Diệm, gunfire could be heard. Speculation about the military coup was rife, causing widespread disorder and urban panic. As the military-controlled radio carried news about the ongoing coup, Châu telephoned the president's office (the "line suddenly went dead"), and then officer colleagues—in the process Châu declined an invitation to join the coup. At a friend's home he waited, apprehensive of the outcome. Diệm and his brother Nhu were both killed early the next morning, November 2, 1963.[127][128][129][130][131]

It was Châu's frank appraisal of the conspiring generals, e.g., Dương Văn Minh, that these prospective new rulers were Diệm's inferiors, in moral character, education, patriotic standing, and leadership ability.[132] The coup remains controversial.[133][134][135][136][137][138][139][140][141]

Châu arranged to fly immediately back to Da Nang, which remained calm. Yet his sense of honor caused him to persist in his loyalty to the murdered president. His attitude was not welcome among some top generals who led the coup. Under political pressure Châu resigned as mayor of Da Nang. Nonetheless, Châu for a while held positions under the new interior minister (and a coup leader), Tôn Thất Đính, and under the new mayor of Saigon, Duong Ngoc Lam.[142][143] Meanwhile, a second coup of January 29, 1964, staged by General Nguyễn Khánh, succeeded in forcing a further regime change.[144][145]

Regarding the war, the American advisors were then "more concerned with security in the provinces" and in 1964 Châu was sent back to Kiến Hòa as province chief. Returning to a familiar setting, his 'homecoming' went well. Châu was comforted to leave Saigon, capital of the "new 'coup-driven' army, with all its intrigues and politics." Vietnamese generals then took little notice of him, but the CIA remained interested in Châu's work. Subsequently, the Minister of Rural Development in Saigon, Nguyen Đức Thang, appointed Châu as national director of the Pacification Cadre Program in 1965.[146][147][148]

Innovative counterinsurgency

In the Vietnam War pacification, a technical term of art,[149][150] became a nagging source of policy disagreement in the American government between its military establishment and civilian leadership. Initially avoided by the military, later, as merely a low-level professional issue, the Army debated its practical value, i.e., the comparative results obtained by (a) employing counterinsurgency techniques to directly pacify a populated territory, versus (b) the much more familiar techniques of conventional warfare used successfully in Europe, then in Korea. The later strategy sought simply to eliminate the enemy's regular army as a fighting force, after which civic security in the villages and towns was expected to be the normal result. Not considered apparently was the sudden disappearance of guerrilla fighters, who then survived in the countryside with local support. later launching an ambush. From the mid-1950s the American strategy of choice in Vietnam was conventional warfare, a contested decision, considered in hindsight a fatal mistake.[151][152][153]

The Army rebuffed President Kennedy's efforts to develop a strong American counterinsurgency capability in general.[156] The Army also declined regarding Vietnam in particular.[157][158] Marine Lt. Gen. Victor Krulak, however, in Vietnam early favored pacification and opposed conventional attrition strategy. Yet Krulak had failed to convince first Gen. Westmoreland, then McNamara at Defense, and ultimately President Johnson.[159][160] Châu, too, spoke with Westmoreland, unsuccessfully.[161]

The Viet Cong generally avoided fielding regular army units until late in the war. The Viet Cong (supported by the North Vietnamese regime), continued through the 1960s to chiefly employ guerrilla warfare in their insurgency to gain political control of South Vietnam.[162] Viet Cong tactics included deadly assaults against civilian officials of the Government of South Vietnam.[163][164][165] The early pacification efforts of Diệm were later overtaken by the American war of attrition strategy, as hundreds of thousands of American soldiers with advanced weaponry arrived in 1965 and dominated the battlefield. Yet after several years the "other war" (pacification) was revived with the initiation of CORDS. By 1967 the military value, as auxiliaries, of American-led pacification teams, became accommodated by the MACV.[166][167][168] Some critics view the initial inability of the U.S. Army command to properly evaluate pacification strategy as symptomatic of its global stature and general overconfidence.[169][170][171]

In the meantime, first under Diệm, the South Vietnamese government with participation by the CIA had contrived to improvise and field various responses to the assaults by the Viet Cong. Châu's contributions to counterinsurgency then were original and significant. Later, heated political controversy would arise over the social ethics and legality of the eventual means developed to "pacify" the countryside.[172]

In Kiến Hòa Province

Châu served as the province chief (governor) of Kiến Hòa Province in the Mekong Delta south of Saigon, 1962–1963 and 1964–1965. Châu had focused "his efforts to devise programs to beat the communists at their own game", in the description of journalist Zalin Grant. At the time Kiến Hòa Province was considered "one of the most communist-dominated" in South Vietnam. In the event, his efforts netted surprising results. Châu's innovative methods and practices proved able to win over the hearts and minds of the people, eventually turning the tide against Viet Cong activity in Kiến Hòa.[174][175][176]

"Give me a budget that equals the cost of only one American helicopter", Châu would say, "and I'll give you a pacified province. With that much money I can raise the standard of living of the rice farmers, and government officials in the province can be paid enough so that they won't think it necessary to steal."[177][178]

From his own experiences with guerrilla tactics and strategy, and drawing on his recent investigations of the Civil Guard, Châu developed a novel blend of procedures for counterinsurgency warfare. Diệm encouraged and supported his experimental approaches to pacification teams and his efforts to implement them in the field.[179]

In Kiến Hòa Province, Châu began to personally train several different kinds of civil-military teams in the skills needed to put the procedures into practice. The purpose of the teams was to first identify and then combat those communist party cadres in the villages who provided civil support for the armed guerrillas in the countryside. The party apparatus of civilian cadres thus facilitated 'the water' in which the "Viet Cong fish" could swim. Châu's teams were instructed how to learn from villagers about the details and identities of their security concerns, and then to work to turn the allegiance or to neutralize the communist party apparatus, which harbored the VC fighters.[180][181] These quasi-civilian networks, which could be urban as well as rural, were called by counterinsurgency analysts the Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI), which formed a "shadow government" in South Vietnam.[182][183][184]

When working as an instructor of the Civil Guard, Châu's innovations had already drawn the interest of several high-level American military officers. Among the first to visit him here in Kiến Hòa was the counterinsurgency expert, Colonel Edward Lansdale."[185][186][187][188][189] Later General Westmoreland, commander of MACV, came to listen to Châu's views, but without positive result.[190][191] Eventually, CIA officer Stewart Methven began working directly with Châu. Pacification methods were adopted by CIA Saigon station chief Peer De Silva, and supported by his superior William Colby who then led CIA's Far East Division.[192][193][194][195]

Census Grievance program

Châu first began to experiment with counterinsurgency tactics while commander of the Civil Guard and Self-Defense Forces in the eastern Mekong delta. Diệm here backed his work.[179] A major spur to his development of a new approach was the sorry state of South Vietnamese intelligence about the Viet Cong. Apparently the communists cadres already knew most South Vietnamese agents who were attempting to spy on them. The VC either fed them misinformation, converted them into double agents, or compromised or killed those few South Vietnamese agents who were effective. Châu had to start again, by trial-and-error practice, to construct better village intelligence. Not only, but also better use of information to deliver effective security for the peasant villagers.[196][197] In doing so Châu combined his idea of village census takers (better intelligence and better use of it) with that of "people's action teams" (PAT) to form a complete pacification program.[198] "Châu apparently had what the Americans with their splintered programs lacked: an overall plan."[199][200]

or the Viet Cong

In Kiến Hòa Province, Châu begin to train five types of specialized teams: census grievance (interviews), social development, open arms (Viet Cong recruitment), security, and counterterror. First, the "census grievance" teams gathered from villagers local information, political and social; such intelligence operations were "critical to the success of the program" and included social justice issues. To compose the 'census grievance' teams, he carefully selected from the Civil Guard individuals for small squads of three to five. "They interviewed every member of the village or hamlet in which they were operating every day without exception." Second, in follow-up responses that used this information, the "social development" teams set priorities and worked to achieve village improvements: bridges, wells, schools, clinics. Third, were the "open arms" teams [Vietnamese: Chieu Hoi],[201] which used village intelligence to counter Viet Cong indoctrination, persuading those supporting the Viet Cong, such as family members and part-time soldiers, that "it was in their interest to join the government side." Fourth, a "security" team composed of "six to twelve armed men" might work with ten villages at a time, in order to provide protection for the other pacification teams and their efforts. Fifth, the "counterterror" teams were a "weapon of last resort."[202][203][204][205][206]

From the intelligence that was obtained from the entire Census Grievance program, "we were able to build a rather clear picture of Viet Cong influence in a given area." Identified were people or whole families supporting the Viet Cong out of fear or coercion, as well as at the other end "hard-core VC who participated and directed the most virulent activities." Evidence about hard-core VC was thoroughly screened and "confirmed at the province level." Only in the presence of active "terrorists" would the 'counterterror' team arrive to "arrest" the suspect for interrogation, and where "not feasible... the ultimate sanction [was] invoked: assassination." Châu emphasized the care and skill which must be given to each step in order to succeed in such a delicate political task. He notes his negative opinion about the somewhat similar Phoenix Program that was later established, inferring that mistakes, and worse, eventually corrupted its operation, which became notorious to its critics.[207][208]

The peasants were naturally very suspicious at first, and reluctant to respond to any questions asked by the "census grievance" teams. Each interview was set to last five minutes. Gradually, however, the people "began to see that we were serious about stopping abuses not only by the Viet Cong but by the government officials and the military as well." Villagers made complaints about issues such as sexual abuse and theft. Charges were investigated, and if proven true, the official or tribal chief was punished by loss of job or by prison. Once in a village the Civil Guard was found to have faked Viet Cong raids in order to steal fish from a family pond. The family was reimbursed. People slowly became convinced of the sincerity of the pacification teams and then "rallied to the government side."[209][210]

Such success carried risk, as "the census grievance teams became prime targets for assassination by the Viet Cong." Information was key. "As our intelligence grew in volume and accuracy, Viet Cong members no longer found it easy to blend into the general populace during the day and commit terrorist acts by night." The 'open arms' teams had started to win back Viet Cong supporters, who might then "convince family members to leave the VC ranks." Other Viet Cong fighters began to fear being captured or killed by the 'counterterror' teams. During Châu's first year a thousand "active Viet Cong guerrillas fled" Kiến Hòa Province.[211] Some disputed the comparative success of Châu and his methods,[212] but his reputation spread as an innovator who could get results.[213][214][215]

As national director

Châu's operational program for counterinsurgency, the 'Census Grievance', was observed and studied by interested South Vietnamese and American officials. Many of his tactical elements were adopted by the CIA and later used by CORDS in the creation of the controversial Phoenix Program. Formerly of the CIA and then as head of CORDS which supervised Phoenix, William Colby "knew that Châu had probably contributed more to pacification than any other single Vietnamese."[216][217]

Châu did not want to kill the Viet Cong guerrillas. He wanted to win them over to the government side. After all most of them were young men, often teenagers, poorly educated, and not really communists....[219][220]

Châu developed ideas, e.g., about subverting the Viet Cong Infrastructure, that were little understood by many American military. However, a small group of dissident officers, often led by Colonel Lansdale, appreciated Châu's work in pacification. These officers, and also CIA agents, opposed the Pentagon's conventional Vietnam strategy of attrition warfare and instead persisted in advocating counterinsurgency methods.[221][222]

The dissidents understood the worth of Châu's appeal to the rural people of Vietnam. As a consequence, over time "a number of the programs Châu had developed in his province were started countrywide."[223]

A major motivation for Châu's approach to counterinsurgency was his nationalism. He favored Vietnamese values, that could inspire the government's pacification efforts and gain the allegiance of the farmers and villagers. Accordingly, Châu voiced some criticism of the 1965 'take-over' of the Vietnam War by the enormously powerful American military. He remembered approvingly that Diệm had warned him that it was the Vietnamese themselves who had to enlist their people and manage their war to victory.[224][225][226] Châu's insistence that Vietnamese officers and agents take leadership positions in the field, and that Americans stay in the background, agreed with Lansdale's view of Vietnamese participation.[227][228]

In 1966 in Saigon the new interior minister in charge of pacification, General Nguyen Đức Thang, whose American advisor was Lansdale, appointed Châu as national director of the Pacification Cadre Program in Saigon.[229][230][231][232] Châu cautiously welcomed the challenging assignment. He realized that Lansdale, Lt. Colonel Vann, and others (dissidents at CIA) had pushed his selection and wanted him to succeed in the job. Châu was ultimately not given the discretion and scope of authority he sought in order to properly lead the national pacification efforts in the direction he advocated. He met opposition from the Americans, i.e., the CIA Saigon leadership, and from his own government.[233][234] His apparent agreement with the CIA station chief on "technical facets" fell short. Châu later wrote:

We never got to the cardinal point I considered so essential: devotion to the nationalist image and resulting motivation of the cadres. ... Such nationalistic motivation could only be successful if the program appeared to be run by Vietnamese; the CIA would have to operate remotely, covertly, and sensitively, so that the project would be seen and felt to be a totally Vietnamese program, without foreign influence.[235]

At the CIA compound in Saigon its leadership, joined there by other American officials from various government agencies, were apparently already satisfied with their approach to running pacification operations in Vietnam.[236][237] Châu then appeared to lack bureaucratic support to implement his innovations.[238][239][240]

Châu relocated to Vũng Tàu (a peninsula south of Saigon) in order to take charge of its National Training Center. A large institution (5,000 trainees for various pacification programs), until 1966 it had been run by Captain Le Xuan Mai. Mai also worked for the CIA and was a Đại Việt proponent. Châu wanted to change the curriculum, but his difficulties with Mai led to a long and bitter struggle before Mai left. The dispute came to involve Vann, Ambassador William J. Porter, the CIA station chief Gordon Jorgenson, pacification minister Thang, and Prime Minister Nguyễn Cao Kỳ. During the personality and political dispute, which grew in complexity, Châu sensed that he had "lost CIA support."[241][242][243][244]

Ultimately, Châu resigned from the army to enter politics, which had been refashioned under the terms of the new constitution.[245] The CIA had brought in "another talented Vietnamese officer, Nguyen Be" who, after working alongside Châu, "took over the Vũng Tàu center" after Châu left. According to journalist Zalin Grant, Be was later given credit by CIA officials (e.g., by Colby) in written accounts as "the imaginative force" instead of Châu, who was "conveniently forgotten".[246] Colby's 1986 book did spotlight "an imaginative provincial chief" in the Delta, but failed to name him.[247]

CIA & CORDS: redesign

CORDS, an American agency, was conceived in 1967 by Robert Komer, who was selected by President Johnson to supervise the pacification efforts in Vietnam. Komer had concluded that the bureaucratic position of CORDS should be within the American "chain of command" of MACV, which would provide for U.S Army support, access to funding, and the attention of policy makers. As the "umbrella organization for U.S. pacification efforts in the Republic of Vietnam" CORDS came to dominate the structure and administration of counterinsurgency.[248][249][250] It supported the continuation of prior Vietnamese and American pacification efforts and, among other actions, started a new program called Phoenix, Phung Hoáng in Vietnamese.[251][252][253]

Controversy surrounded the Phoenix Program on different issues, e.g., its legality (when taking direct action against ununiformed communist cadres doing social-economic support work), its corruption by such exterior motives of profit or revenge (which led to the unwarranted use of violence including the killing of bystanders), and the extent of its political effectiveness against the Viet Cong infrastructure.[254][255][256] Colby, then head of CORDS, testified before the Senate in defense of Phoenix and about correcting acknowledged abuses.[257][258] Châu, because of its notorious violence, became disillusioned and so eventually often hostile to the Phoenix Program.[259][260]

From Châu's perspective, what had happened was America's take-over of the war, followed by their taking charge of the pacification effort. Essentially misguided, it abused Vietnamese customs, sentiments, and pride. It did not understand the force of Vietnamese nationalism. The overwhelming presence in the country of the awesome American military cast a long shadow. The war intensified. Massive bombing campaigns and continual search and destroy missions devastated the Vietnamese people, their communities, and the countryside.[261][262][263][264] The presence of hundreds of thousands of young American soldiers led to social corruption.[265][266][267][268] The American civilian agencies with their seemingly vast wealth, furthered the villagers' impression that their government's war was controlled by foreigners. Regarding Phoenix, its prominent American leadership put Vietnamese officials in subordinate positions. Accordingly, it was more difficult for the Phoenix Program to summons in villagers the Vietnamese national spirit to motivate their pacification efforts, more difficult to foster the native social cohesion needed to forestall corruption in the ranks.[269][270][271][272][273]

Further, Châu considered that pacification worked best as a predominantly civic program, with only secondary, last resort use of paramilitary tactics. Châu had crafted his 'Census Grievance' procedures to function as a unified whole. In constructing Phoenix, the CIA then CORDS had collected components from the various pacification efforts ongoing in Vietnam, then re-assembled them into a variegated program that never achieved the critical, interlocking coherence required to rally the Vietnamese people. Hence much of the corruption and lawless violence that plagued the program and marred its reputation and utility.[274][275][276][277][278]

Commentary & opinion

according to David Kilcullen (2006)

The literature on the Vietnam War is vast and complex, particularly regarding pacification and counterinsurgency.[279] Its contemporary relevance to the "War on Terror" following 9/11/2001 is often asserted.[280] Of those commentators discussing Châu and his methods, many but not all share or parallel Châu's later views on the subsequent Phoenix Program: that his subtle, holistic counterinsurgency tactics and strategy in the hands of others acquired, or came to manifest, repugnant, self-defeating elements. Châu wrote in his memoirs that the Phoenix Program, which arguably emerged from his Census Grievance procedures, became an "infamous perversion" of it.[281] The issues were convoluted, however; Châu himself could appear ambiguous. Indeed, general praise for American contributions to pacification was offered by an ARVN senior officer.[282][283]

In the media, the Phoenix Program under Komer and Colby became notorious for its alleged criminal conduct, including putative arbitrary killing. Critics of the war often named Phoenix as an example of America's malfeasance. Journalist Zalin Grant writes:

From the start Phoenix was controversial and a magnet for attracting antiwar protests in the States. Some of the suspicion about the program grew from its very name. ... [¶] [Another cause was] Colby's and Komer's insistence on describing Phoenix in bureaucratic terms that were clear only to themselves. ... [This] contributed to a widespread belief that they were out to assassinate the largely innocent opponents of the Saigon government and trying to cover up their immoral acts with bewildering obfuscations.[284]

Frances FitzGerald called it an instrument of terror, which in the context of the war "eliminated the cumbersome category of 'civilian'."[285] Phoenix became the nota bene of critics, and the bête noire of apologists. Commentary when focused on the Phoenix Program often turned negative, and could become caustic and harsh.[286][287][288][289][290][291][292][293] Others saw it differently, in whole or in part, evaluating the redesigned pacification effort in its entirety as the use of legitimate tactics in war, and focused on what they considered its positive results.[294][295][296][297][298][299][300][301][302][303] [under construction]

Yet subtleties of grey appear to permeate both the black and the white of it, precluding one-dimensional conclusions.[304][305][306]

As civilian politician

After the impasse over implementation of his pacification program, and friction with CIA, Châu considered alternatives. Traveling to Huế, he spoke with his father. With his wife he discussed career choices.[citation needed] The political situation in South Vietnam was changing. As a result of demands made during the second Buddhist crisis of early 1966,[308][309] national elections were scheduled. During his career as an army officer, Châu had served in several major civilian posts: as governor of Kiến Hòa Province (twice), and as mayor of Da Nang the second largest city. Châu decided in 1966 to leave the ARVN. He ran successfully for office the following year. Châu then emerged as a well-known politician in the capital Saigon. Nonetheless, he later ran afoul of the political establishment, was accused of serious crimes in 1970, and then imprisoned for four years.[310][311]

South Vietnam was not familiar with the conduct of fair and free democratic elections. The Diệm regime (1954–63) had staged elections before in South Vietnam, but saw their utility from a traditional point of view. As practiced in similarly situated countries, elections were viewed as a "national holiday" event for the ruling party to muster its popular support and mobilize the population. In order to show its competence, the government worked to manage the election results and overawe its opponents.[312][313][314][315][316]

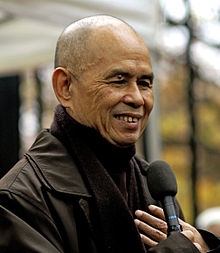

Then in the spring of 1966, the Buddhist struggle movement led by Thích Trí Quang[317] obligated the military government to agree to democratic national elections, American style, in 1966 and 1967. The Buddhists had staged massive civil demonstrations (Phật giáo nổi dậy) in Huế and Da Nang, which resonated in Saigon and across the country. Eventually put down by the military, the Buddhists had demanded a return to civilian government through elections. The American embassy privately expressed fear of such a development.[318][319][320][321][322][323][324] In the event, the election campaigns were more fairly contested than before in Vietnam, but were not comparable to elections held in mature democracies.[325][326][327]

Lack of civil order and security, due to the ongoing war, prevented voting in about half the districts. The procedure of casting ballots and counting them was generally controlled by officials of the Saigon government who might manipulate the results, depending. Candidates were screened beforehand to eliminate politicians with disapproved views.[328] Forbidden to run were pro-communists, and also "neutralists" (pointedly, "neutralists" included Buddhist activists who favored prompt negotiations with the VC to end to the war).[329][330][331][332][333][334] A majority of Vietnamese were probably neutralists.[335][336] Campaigning itself was placed under restrictions.[337][338][339] A favorable view held that the election was an "accomplishment on the road toward building a democratic political system in wartime."[340][341][342] Châu himself was optimistic about the people casting their votes.[343]

Elected to Assembly

Châu was elected to the House of Deputies of the National Assembly from the predominantly rural Kiến Hòa Province. The campaigns leading to the October 1967 vote were unfamiliar phenomena in South Vietnam, and called on Châu to make difficult decisions on strategy and regarding innovation in the field. He had wanted to advance the cause of a new Vietnam, a modern nation that would evolve from its own culture and traditions. With the lessons he'd learned from his experiences in counterinsurgency warfare, he was also determined to refashion pacification efforts, to improve life in the villages, and to rally the countryside to the government's side. To spell out such a program Châu wrote a book in Vietnamese, published in 1967, whose title in translation was From War to Peace: Restoration of the Village.[344][345]

During the six-week campaign Châu crisscrossed the province, where he had twice served as governor, contacting residents to rally support. He competed with nineteen candidates for two openings in the House of Deputies. Châu claimed to enjoy "total support, either tacit or openly, from all Kiến Hòa 's religious leaders", including Buddhist and Catholic. To them he summarized his campaign: first, to listen, to hear their voices and investigate their complaints; second, "to work toward an ending of the war that would satisfy the honor and dignity of both sides."[346][347]

After Châu had resigned from the army, while he was preparing his run for office, his communist brother Trần Ngọc Hiền unexpectedly visited him in Saigon. Hien did not then reveal his ulterior motives, but later Châu discovered that Hien had been sent by his VC superiors in order to try to turn Châu. Châu as usual kept his brother at arm's length, although he also entertained a brotherly concern for his safety. Both brothers, Châu and Hien, once again decidedly rejected the crafted political arguments of the other. Hien mocked Châu's run for office; Châu curtly told his brother to stay out of the election. Several years earlier in 1964 or 1965 Hien had visited Châu in Kien Hoa Province. They had not met for 16 years. Hien requested that Châu arrange a meeting with the American ambassador Lodge. Promptly Châu had informed the CIA of his brother's visit. The Embassy through the CIA sought to make use of the "back channel" contact, regarding potential negotiations with Hanoi. But later Hien broke off further communication.[348][349]

During the campaigning Châu's virtues and decorated military career attracted some attention from the international press. His youth in the Việt Minh fighting the French, followed by his decision to break with the communists, also added interest. About him journalist Neil Sheehan later wrote that to his American friends, "Châu was the epitome of a 'good' Vietnamese." Sheehan states:

[Châu] could be astonishingly candid when he was not trying to manipulate. He was honest by Saigon standards, because though advancement and fame interested him, money did not. He was sincere in his desire to improve the lives of the peasantry, even if the system he served did not permit him to follow through in deed, and his four years in the Việt Minh and his highly intelligent and complicated mind enabled him to discuss guerrilla warfare, pacification, the attitude of the rural population, and the flaws in Saigon society with insight and wit.[350]

Apparently to some foreigners Châu seemed to conjure up a mercurial stereotype. Michael Dunn, chief of staff at the American Embassy under Lodge, was puzzled by Châu. He claimed to not be able to tell "which Châu was the real Châu. He was a least a triple personality." Dunn explained and continued:

There were so many Americans interested in Vietnam and so few interesting Vietnamese. But Châu was an extraordinary fellow. ... Many people thought Châu was a very dangerous man, as indeed he was. In the first place, anybody with ideas is dangerous. And the connections he had were remarkable.[351]

Three days before the vote Châu learned of a secret order by provincial governor Huynh Van Du to rig the vote in Kiến Hòa. Châu quickly went to Saigon to see his long-time friend Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, the newly elected president.[352] Thiệu said he could not interfere as the Vice President Nguyễn Cao Kỳ had control over it. On his way out Châu told General Huỳnh Văn Cao that he would "not accept a rigged election." Cao had prominently campaigned for Thiệu–Kỳ, and himself had led a Senate ticket to victory. Somehow, the governor did rescind his secret order. "He [Châu] won a seat in the National Assembly election in 1967 in one of the few unrigged contests in the history of the country", stated The New York Times. Châu got 42% among 17 candidates, most of whom were locals. "It was a tremendous tribute to his service as province chief", wrote Rufus Phillips, an American officer in counterinsurgency. The victory meant a four-year term as a representative in the reconstituted national legislature, where he would speak for the 700,000 constituents of Kiến Hòa province.[353][354][355][356][357]

In the legislature

Along with like-minded members of the Assembly, Châu had initially favored a legislative group that, while remaining independent of Thiệu, would generally back him as the national leader. Based on his long-time military association, Châu had spoken with his friend Thiệu soon after the Assembly elections. He encouraged the new civilian president to "broaden his base with popular support from the grassroots level". He suggested that Thiệu reach an understanding with the nascent legislative group. Châu hoped Thiệu would consider how to end the widespread pain and violence of the debilitating war. Eventually, the Thiệu regime might establish a permanent peace by direct negotiations with the VC and the north. With his own strategies in view, Thiệu bypassed such plans. Châu, too, stayed out of the pro-Thiệu bloc, thereby not jeopardizing his support from "southern Catholics and Buddhists".[358][359]

In the meantime, in a secret ballot Châu was chosen by his legislative peers as their formal leader, i.e., as the Secretary General in the House of Deputies.[360] Such office is comparable perhaps to the American Speaker of the House.[361] An American academic, who then closely followed South Vietnamese politics, described the politician Châu:

Tran Ngoc Chau was the Secretary-General of the House. He was universally respected as a fair individual and one who, during his tenure as an officer of the House, had maintained a balance between criticism and support of [Thiệu's] government based on his perception of the national interest.[362]

Meeting in Saigon, the Assembly's agenda in late 1967 included establishing institutions and functions of the state, as mandated by the 1966 constitution. The new government structures encompassed: an independent judiciary, an Inspectorate, an Armed Forces Council, and provisions for supervision of local government, and for civil rights. The House soon turned to consider its proper response to the strong power of the President. Such "executive dominance" was expressly made part of the new constitution. In managing its business and confronting the issues, the Assembly's initial cliques, factions, and blocs (chiefly stemming from electoral politics) were challenged. They realigned.[363][364]

Châu carefully steered a political course, navigating by his moderate Buddhist values.[365] He maintained his southern Catholic support, part of his rural constituency; he also appealed to urban nationalists.[366] The street power of the Buddhist struggle movement, whose leaders had successfully organized radical activists in the major demonstrations of 1963 and 1966, had collapsed.[367][368][369][370][371] Yet many other Buddhists were elected in 1967,[372] and prominent Buddhists supported Châu's legislative role.[373] Among the various groups of deputies, Châu eventually became a member of the Thống Nhất ("Unification bloc"). Professor Goodman described it as "left of center" yet nationalist, associated with Buddhist issues, and "ideologically moderate". The legislative blocs, however, were fluid; "the efficiency of blocs, as measured by their cohesion, appeared linked not to their rigidity but to the level of cooperation achieved among them."[374]

The violent Tet Offensive of January 1968 suddenly interrupted the politics of South Vietnam.[375][376] Thiệu requested the legislature to grant him emergency powers, but Châu speaking for many deputies "declared that the executive already had sufficient powers to cope... and suggested that the present burden be shared between both branches". The Assembly voted 85 to 10 against the grant.[377][378]

Tet also sparked new calls for a national draft. In the back and forth with legislators, the pro-Army government of former generals criticized its civilian political opponents for their alleged avoidance of military service. These liberals then countered by charging that the sons of senior Army officers were currently themselves dodging service; names were named. Châu listened, at first sharply resenting such urban liberals as Ngô Cong Đức. Yet, as he heard the critics charge the highly politicized, coup-prone Army with malfeasance, it resonated with his own experience. In part the military was "corrupt and incompetent". It often based "promotions on favoritism rather than merit" which weakened the Army and "made it easy for the Communists to spread their message". Gradually Châu realized that these civilian politicians "formed the most active group of Southerners opposed to the government's abuse of power" and that he shared their "fight for reform".[379][380]

Corruption had become ubiquitous; it damaged South Vietnam's prospects.[381][382][383] The ragged war economy, amid destruction and death, and inflation, created stress in the population, yet presented novel business opportunities, not all legitimate.[384] Incoming American war assistance multiplied many fold, as did American aid to millions of Vietnamese refugees caused by the war's escalation. Accordingly, a major source of wealth was the import of vast quantities of American goods: to support military operations, to supply hundreds of thousands of troops, and to mitigate 'collateral damage'. Misappropriation of these imports for commercial resale became a widespread illegal activity. Its higher-end participants were often Vietnamese officials, military officers and their wives.[385][386][387][388][389][390]

Other forms of corruption were common. In the government, the hidden selling of their votes by some elected deputies disgraced the process. A pharmacist, Nguyen Cao Thang, was Thiệu's liaison with the legislature. Part of his duties apparently included delivery of cash payments to deputies. Châu started a political campaign against corruption in general and against the "bag man" Thang in particular.[391][392] In the National Assembly Châu "had attracted a bloc of followers whose votes could not be bought. He had also aroused Thiệu's ire by attacking government corruption."[393]

As his legislative experience accumulated, Châu thought of starting "a political party with a nationwide grassroots infrastructure". He had reasoned that many fellow deputies were unfortunately not connected to the people who voted, but more to artificial, inbred political networks. Such politicians, hopefully, would be denied reelection. In 1968 Châu spoke with two CIA agents; one offered secret financing to set up and organize a new political party, but it had to be supportive of President Thiệu and the war. The new party project appealed to Chau, but the CIA's secret deal did not. Instead Châu suggested the need for a center nationalist party, independent of the military, and "a new national agenda and policies that could win the support of most of the people." The CIA, however, required that their recipients favor Thiệu, and conform to U.S. policy on the war.[394][395][396]

During this period Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker was being cooperative regarding Thiệu's authoritarian rule.[397][398] Châu sensed his exposure to powerful elements of the Saigon establishment.[399][400]

Peace negotiations

Following the aftermath of his election to the National Assembly in October 1967, Châu traveled to America. He saw the early stages of their 1968 elections and the surge in anti-war sentiment about Vietnam. In America, direct entry into negotiations to end the war were contemplated.[401][402] In Washington Châu gave lectures on the conflict, and conversed with experts and officials (many he'd met in Vietnam), and with members of Congress. Yet the Tet Offensive began the day of Châu's chance to talk with President Johnson, and the meeting was cancelled.[403] Several months after Châu's journey, negotiations between the North Vietnamese and the Americans began in Paris (10 May 1968).[404]

Châu and others sharply criticized the peace negotiations: in place of the Republic of Vietnam stood the Americans. Vietnamese dignity was impugned. It seemed to confirm the Republic's status as a mere client of American power. Instead, Châu insisted, Saigon should open negotiations with the communists, both VC and the North Vietnamese regime. Meanwhile, the Americans should remain off-stage as an observer, who'd support to Saigon.[405]

In this way a ceasefire might be arranged and the hot war (which then continued to devastate the South and kill an enormous number of its citizens) halted, allowing for the pacification of the combatants. Accordingly, the conflict could be politicized and thus returned to Vietnamese civilian control. A peace could return to the countryside, the villages, the urban areas. Thereafter South Vietnamese nationalist politicians, perhaps even in a coalition government, could nonetheless wage a democratic struggle against the VC. The nationalists might attract popular support by pitting Vietnamese values against communist ideology. Yet the Thiệu regime's policy then condemned outright any negotiations with the VC, as either communist or communist inspired.[406][407] The Thiệu regime in Saigon had legally prohibited public advocacy of peace negotiations or similar deal-making with the communists.[408] "Châu wanted reasonable negotiations and a settlement while Saigon still retained bargaining power. Of course, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu's policy aimed to prevent any such settlement."[409] [Under construction]

Political trial, prison

In 1970, Châu was arrested for treason against the Republic due to his meeting with his brother Hien, who had since the 1940s remained in the Việt Minh and subsequent communist organizations as a party official. Articles about Châu's confinement appeared in the international media. The charges were considered to be largely politically motivated, rather than for questions of loyalty to country.[410][411][412][413] Yet in February 1970 Châu was sentenced to twenty years in prison. That May the Vietnamese Supreme Court held Châu's arrest and conviction unconstitutional, but Thiệu refused him a retrial.[414] [Under construction]

Although released from a prison cell by the Thiệu regime in 1974, Châu continued to be confined, being kept under house arrest in Saigon.[415] In April 1975, during the confusion surrounding the unexpectedly swift Fall of Saigon, and America's ill-planned withdrawal from Vietnam, Châu and his family were left behind.[416][417] Three Americans, a reporter and an embassy officer, and a retired general with MAAG, each tried to get Châu and his family evacuated during the final few days. Yet blocking their efforts were the sudden turmoil, the mobs, and the general confusion and danger in Saigon. The congestion and the chaotic traffic further obstructed all the exit routes. He and his wife were anxious about their fraught and pregnant daughter, which caused Châu's family "to resign ourselves to whatever we, as losers of the war, must face in the future."[418]

Under the Communist regime

The war ended April 30, 1975, with the surrender of South Vietnam to the North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN). A "grand victory celebration" was scheduled in Saigon for May 15, featuring North Vietnamese president Tôn Đức Thắng.[419][420][421]

Trương Như Tảng, then the NLF's Minister of Justice, called the days following victory "a period of rapid disenchantment". In southern Vietnam, a major issue of reunification became how to incorporate former enemies from the long civil war. In May, members of the defeated Thiệu regime were instructed to report for a period of re-education to last three, ten or 30 days depending on their rank. Such a seemingly magnanimous plan won popular approval. Hundreds of thousands reported. Several months passed, however, without explanation; few were released. Tảng reluctantly realized that the period of confinement initially announced had been a ruse to smooth the state's task of arrest and incarceration. He confronted the NLF President Huỳnh Tấn Phát about this cynical breach of trust with the people. Tảng was brushed off. Next came a wave of arbitrary arrests that "scythed through the cities and villages". Tảng worked to remedy these human rights abuses by drafting new laws, but remained uncertain about their enforcement. "In the first year after liberation, some three hundred thousand people were arrested", many held without trial for years. Tảng's post would soon be eliminated in the reunification process, and his former duties performed by a northerner appointed by the Communist Party of Vietnam in Hanoi.[422][423][424]

Re-education camp

In June while Châu was home with his wife and children, three armed soldiers came to the home, then handcuffed Châu and took him away for interrogation. Afterwards sent "temporarily" to a re-education camp, he was indoctrinated about the revolution. Not allowed visitors nor told an expected duration, Châu would remain confined at various locations for about three years.[425][426][427]

At what Châu came to call the "brainwashing campus" he studied Communist ideology. He found himself in company with many former civilian officials of the defunct Saigon government. Among the several thousands in this prison he found "Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Trần Minh Tiết and hundreds of other senior judges, cabinet members, senators, congressmen, provincial governors, district chiefs, heads of various administrative and technical departments, and political party leaders". Châu later estimated the country-wide total of such prisoners in the hundreds of thousands. Also included were military officers, police officers, minor officials, and school teachers.[428][429][430]

Isolated, in rough conditions, the inmates were occupied from 5 a.m. to 10 p.m. daily. The first three months the prisoners worked constructing and fixing up the camp itself: "sheet-iron roofs, corrugated metal walls, and cement floors", all surrounded by concertina wire and security forces. At this campus lectures were given, usually by senior army officers from the north, presenting the Communist version of Vietnamese history. They spoke of crimes committed by the Americans and their puppets, the bright communist future ahead, and the opportunity now for prisoners to remedy their own "mischief and crimes". Ideological literature was available. Group discussion sessions were mandatory; to participants they seemed to last forever. Their 'education' was viewed by many inmates as a form of punishment. Châu thought the northern army officers "believed firmly in their teachings even when they didn't know what they were talking about."[431][432]

Prisoners might fall ill, become chronically weak, or otherwise lose their health and deteriorate. "Some prisoners went crazy. There were frequent suicides and deaths." Each inmate was forced to write an autobiography that focused on their political views and that confessed their errors. Afterwards, each was separately interviewed regarding personal details and requested to rewrite sections. Châu was questioned in particular about his CIA connections and made to rewrite his autobiography five times. After 14 months, outside visitors were allowed into the camp, with families often shocked at the weakened appearance of their kin. Châu's wife and children "did not recognize me at first because I had lost forty pounds." It also became clear to the prisoners that close family members 'outside' were being punished for the political 'crimes' of those held inside.[433][434][435][436] Châu's wife arranged for 25 members of his family living in the north to sign a petition requesting clemency.[437]

After two and a half years, 150 inmates including Châu were moved to Thủ Đức prison near Saigon. Their new status and location was subject to transfer to northern Vietnam, where long terms at hard labor were the norm.[438] They joined here others held in the re-education grind, those deemed the "worst criminals". Among them were Buddhist monks and Catholic clergy. After his identity was confirmed, Châu feared his imminent execution. Instead, moved to the old police headquarters in Saigon, he was put in solitary confinement. He practiced yoga and meditation.[439][440] After three weeks in solitary he was taken to two elder Communists and interrogated. One told Châu his crimes had resulted in "the killing of tens of thousands of people throughout the country" and demanded a response. Châu replied that "I am defeated, I admit. Ascribe to me whatever crimes you want." Instructed to rewrite his autobiography, over the next two months, given better food and a table and chair, Châu wrote 800 pages, covering "the crimes I had committed against the people and the revolution".[441][442]

Châu noticed that the four other inmates receiving the same treatment as him were "notables of the Hòa Hảo, a Buddhist-oriented religion rooted in the Mekong Delta [and] known as staunchly anti-Communist."[443] The Communists were not worried about careerist opponents, whose "brand of anti-Communism ceased to exist the day Americans stopped providing subsidies." But principled anti-Communist might mask their convictions and remain a "potential threat". A senior Communist official uncharacteristically acted friendly toward inmate Châu. Yet this official told Châu he "was the victim of a false illusion" that caused him to be "an anti-Communist by conviction" and hence "a greater threat to the revolution than people who opposed Communism only out of self-interest".[444]

Three questions were then put to Châu: his personal reasons for opposing the communist revolution; his motivation to help the Americans; and, the story behind his peace proposal of 1968. The senior officials wanted more precise information in order to understand better the "enemy of the people" types like Châu. Châu felt specially targeted for his personal convictions as a Buddhist and nationalist, which motivated him to serve the people. This was key to his three answers. The process became an issue, Châu mused, not really of courage but of his sense of "personal honor". The senior interrogator told him his political nationalism was mistaken, but that Châu was being given "an opportunity to revive your devotion to serve the people." Then he surprised Châu by informing him of his release. Châu "still suspicious" wrote a letter "promising to do my best to serve the country". A few days later, his wife and eldest daughter arrived to take him home.[445][446][447]

Release, escape by boat

After his unexpected release from prison in 1978, Châu went to live with his wife and children. He received family visitors, including his communist brother Trần Ngọc Hiền. Eight years earlier Hien's arrest in Saigon by the Thiệu regime had led to Chau's first imprisonment. Once a highly placed Communist intelligence officer, Hien had become disillusioned by the harsh rule imposed by victorious Hanoi. Subsequently, Hien's advocacy of Buddhist causes had gotten him disciplined then jailed by the Communist Party of Vietnam. Châu's sister and her husband, a civil engineer, also visited Châu. They had come down from northern Vietnam, where they had been living for twenty-five years.[448][449][450]

In the late 1970s top Communist leaders in the north seemed to understand victory in the exhausting war as the fruit of their efforts, their suffering, which entitled northern party members to privileges as permanent officials in the south.[451] Châu viewed Communism negatively, but not in absolutist terms. While serving in the Việt Minh during the late 1940s, Chau had admired his companions' dedication and sacrifice, and the Communist self-criticism process; his break with them was due to his disagreement with their Marxist–Leninist ideology. Yet now, released from re-education camp and back in 'occupied' Saigon, Châu became convinced that in general the ruling Communists had lost their political virtue and were "corrupted" by power.[452][453] When the country was divided in 1954, hundreds of thousands left the northern region assigned to Communist rule, journeying south. After the 1975 Communist military victory had reunited Vietnam, hundreds of thousands would flee by boat.[454]

Following Châu's release, the friendly senior official from the prison visited him. He told Châu he'd been freed so that he could inform on his friends and acquaintances. Châu was given a position at the Social Studies Center in Saigon, an elite institution linked to a sister organization in Moscow.[455] Chau was assigned the file on the former leaders of the defunct South Vietnamese government. From indications at work he understood his role would also include writing reports on his miscellaneous contacts with fellow Vietnamese, which he silently resolved to avoid.[456][457]

In 1979, Châu and his family (wife and five of his children) secretly managed to emigrate from Vietnam illegally by boat. They arranged to join with a Chinese group from Cholon also intent on fleeing Vietnam. An unofficial policy then let Chinese leave if they paid the police $2500 in gold per person.[458][459] On the open seas, a Soviet Russian ship sighted by chance provided them with supplies. The journey was perilous, the boat over-crowded. When they landed in Malaysia the boat sank in the surf. Malaysia sent them to an isolated island in Indonesia. From there Châu with a bribe got a telegram to Keyes Beech, a Los Angeles Times journalist in Bangkok. Finally, with help from Beech, they made their way to Singapore and a flight to Los Angeles. Their arrival in America followed by several years the initial wave of Vietnamese boat people.[460][461][462]

Later years in America

In 1980, shortly after his arrival in California, Châu had been interviewed by Neil Sheehan, who then wrote an article on Communist re-education camps in Vietnam. It appeared in The New York Times.[463] Châu's friend Daniel Ellsberg had given Sheehan his contact information. Of Châu in the article Ellsberg said, "He was critical of the communists but in a judicious manner." Sheehan, however, did not realize at the time the actual extent of the Communist repression in Vietnam. "There was no blood bath", Sheehan quoted Châu as saying.[464] For Châu the immediate impact of the article was the manifest scorn and threats from some fellow Vietnamese refugees, who were his neighbors. Ellsberg complained to Sheehan that although factually correct he had mischaracterized Châu's opinions. "You got him into trouble", Ellsberg told him. Châu, his wife and his children, weathered the angry storm, according to Zalin Grant.[465]

Châu and his family settled in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles, rather than in the larger Vietnamese neighborhoods in nearby Orange County. Becoming acculturated, and improving their English, his children became achievers and entered various professional careers. Châu himself learned computer programming and later purchased a home. After five years Châu applied for American citizenship and recited the oath.[466][467]

A reconciliation eventually occurred between Châu and Thiệu, his friend since 1950, yet in the 1970s a punishing political antagonist.[468] From time to time Châu granted interviews, including for Sheehan's 1988 book A Bright Shining Lie which won a Pulitzer.[469] In April, 1995, he gave an interview over three days to Thomas Ahern, who had been commissioned by the CIA to write the official history of its involvement in Vietnam during the war.[470] Châu returned to Vietnam for a visit in 2006.[471] In 1991 Châu had accepted an invitation to visit Robert Thompson in England, where he talked shop with the counterinsurgency expert of 1950s Malaysia.[472]

In 2013 he published his book of memoirs which recount experiences and politics during the Vietnam War. Writer Ken Fermoyle worked with Châu on the book, a product of many years.[473][474][475]

Châu appears before the camera several times, talking about his experiences and the situations during the conflict, in the 2017 PBS 10-part documentary series The Vietnam War produced by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.[4]

Châu died on June 17, 2020, at a hospital in West Hills, Los Angeles. He was 96, and had contracted COVID-19.[4]

Bibliography

Primary

- Tran Ngoc Châu with Ken Fermoyle, Vietnam Labyrinth. Allies, enemies, & why the United States lost the war (Lubbock: Texas Tech University 2012).

- Tran Ngoc Châu, "The curriculum was designed to 'detoxicate' us" pp. 475–480 in Appy (2003).

- Tran Ngoc Châu with Tom Sturdevant, "My War Story. From Ho Chi Minh to Ngô Đình Diệm" at pp. 180–209 in Neese & O'Donnell (2001).

- Tran Ngoc Châu, "Statement of Tran Ngoc Chau" in The Antioch Review (Fall/Winter 1970–1971), pp. 299–310, translated, annotated, and with an introduction by Trần Văn Dĩnh and Daniel Grady.

- Tran Ngoc Châu, two papers (via Daniel Ellsberg) and open letter, pp. 365–381, 357–360, in United States Senate (1970).[476]

- Tran Ngoc Châu, a 1968 book on the peace talks [in Vietnamese].[477]

- Tran Ngoc Châu, From War to Peace: Restoration of the Village (Saigon 1967) [In Vietnamese].[478][479][480]

- Tran Ngoc Châu, Pacification Plan, 2 volumes (1965 ) [unpublished].[481]

- Ken Fermoyle, "Hawks, Doves and the Dragon" in Pond (2009), pp. 415–492.[482]

- Mark Moyar, "Could South Vietnam Have Been Saved? New scholarship raises questions about antiwar consensus of Vietnam historians", in Wall Street Journal of June 28, 2013.[483]

- John O'Donnell, "The Strategic Hamlet Program in Kien Hoa Province, South Vietnam: A case study of counter-insurgency" pp. 703–744 in Kunstadter (1967).[484]

- Neil Sheehan, "Ex-Saigon Official Tells of 'Re-education' by Hanoi" in The New York Times, January 14, 1980, pp. A1, A8.

- Zalin Grant, Facing the Phoenix. The CIA and the political defeat of the United States in Vietnam (New York: Norton 1991).[485][486]

- Elizabeth Pond, The Châu Trial in Vietnamese translation as Vụ Án Trần Ngọc Châu (Westminster: Vietbook USA 2009).[487]

Vietnam War

Counterinsurgency

- Thomas L. Ahern Jr., Vietnam Declassified. The CIA and counterinsurgency (University of Kentucky 2010).

- Dale Andradé, Ashes to Ashes. The Phoenix Program and the Vietnam War (Lexington: D.C. Heath 1990).

- William Colby with James McCargar, Lost Victory. A firsthand account of America's sixteen-year involvement in Vietnam (Chicago: Contemporary Books 1989).

- Stuart A. Herrington, Silence was a weapon. The Vietnam War in the villages (Novato: Presidio Press 1982); revised edition after security restrictions lifted to allow discussion of the CIA's role, re-titled Stalking the Vietcong. Inside operation Phoenix. A personal account (Presidio 1997).

- Richard A. Hunt, Pacification. The American struggle for Vietnam's hearts and minds (Boulder: Westview 1995).

- Edward Geary Lansdale, In the Midst of Wars (NY: Harper & Row 1972; reprint: Fordham University 1991).

- Mark Moyar, Phoenix and the Birds of Prey. The CIA's secret campaign to destroy the Viet Cong (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press 1997).

- Nguyen Cong Luan, Nationalist in the Viet Nam Wars. Memoirs of a victim turned soldier (Indiana University 2012).

- Rufus Phillips, Why Vietnam Matters. A eyewitness account of lessons not learned (Annapolis: Naval Institute 2008).

- Douglas Pike, Viet Cong. The organization and techniques of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (M.I.T. 1966).

- Ken Post, Revolution, Socialism & Nationalism in Viet Nam. Vol. IV, The failure of counter-insurgency in the South (Aldershot: Dartmount 1990).