The trifunctional hypothesis of prehistoric Proto-Indo-European society postulates a tripartite ideology ("idéologie tripartite") reflected in the existence of three classes or castes—priests, warriors, and commoners (farmers or tradesmen)—corresponding to the three functions of the sacral, the martial and the economic, respectively. The trifunctional thesis is primarily associated with the French mythographer Georges Dumézil,[1] who proposed it in 1929 in the book Flamen-Brahman,[2] and later in Mitra-Varuna.[3]

Three-way division

According to Georges Dumézil (1898–1986), Proto-Indo-European society had three main groups, corresponding to three distinct functions:[2][3]

- Sovereignty, which fell into two distinct and complementary sub-parts:

- one formal, juridical and priestly but worldly;

- the other powerful, unpredictable and priestly but rooted in the supernatural world.

- Military, connected with force, the military and war.

- Productivity, herding, farming and crafts; ruled by the other two.

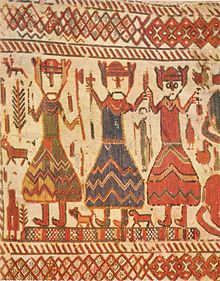

In the Proto-Indo-European mythology, each social group had its own god or family of gods to represent it and the function of the god or gods matched the function of the group. Many such divisions occur in the history of Indo-European societies:

- Southern Russia: Bernard Sergent associates the Indo-European language family with certain archaeological cultures in Southern Russia and reconstructs an Indo-European religion based upon the tripartite functions.[4]

- Early Germanic society: the supposed division between the king, nobility and regular freemen in early Germanic society.[5]

- Norse mythology: Odin (sovereignty), Týr (law and justice), the Vanir (fertility).[6][7][note 1] Odin has been interpreted as a death-god[9] and connected to cremations,[10] and has also been associated with ecstatic practices.[11][10]

- Classical Greece: the three divisions of the ideal society as described by Socrates in Plato's The Republic. Bernard Sergent examined the trifunctional hypothesis in Greek epic, lyric and dramatic poetry.[12]

- India: the three Hindu castes, the Brahmins or priests; the Kshatriya, the warriors and military; and the Vaishya, the agriculturalists, cattle rearers and traders. The Shudra, a fourth Indian caste, is a peasant or serf. Researchers believe that Indo-European-speakers entered India in the Late Bronze Age, mixed with local Indus Valley civilisation populations and may have established a caste system, with themselves primarily in higher castes.[13][14]

Reception

Supporters of the hypothesis include scholars such as Émile Benveniste, Bernard Sergent and Iaroslav Lebedynsky, the last of whom concludes that "the basic idea seems proven in a convincing way".[15]

The hypothesis was embraced outside the field of Indo-European studies by some mythographers, anthropologists and historians such as Mircea Eliade, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Marshall Sahlins, Rodney Needham, Jean-Pierre Vernant and Georges Duby.[16]

On the other hand, Nicholas Allen concludes that the tripartite division may be an artefact and a selection effect, rather than an organising principle that was used in the societies themselves.[17] Benjamin W. Fortson reports a sense that Dumézil blurred the lines between the three functions and the examples that he gave often had contradictory characteristics,[18] which had caused his detractors to reject his categories as nonexistent.[19] John Brough surmises that societal divisions are common outside Indo-European societies as well and so the hypothesis has only limited utility in illuminating prehistoric Indo-European society.[20] Cristiano Grottanelli states that while Dumézilian trifunctionalism may be seen in modern and medieval contexts, its projection onto earlier cultures is mistaken.[21] Belier is strongly critical.[22]

The hypothesis has been criticised by the historians Carlo Ginzburg, Arnaldo Momigliano[23] and Bruce Lincoln[24] as being based on Dumézil's sympathies with the political right. Guy Stroumsa sees those criticisms as unfounded.[25]

See also

Notes

References

Sources

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1990), Gods and Myths of Northern Europe, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-013627-4

- de Vries, Jan (1970), Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte, volume 2. 2nd ed. repr. as 3rd ed (in German), Walter de Gruyter, OCLC 466619179

- Polomé, Edgar Charles (1970), "The Indo-European Component in Germanic Religion", in Puhvel, Jaan (ed.), Myth and Law Among the Indo-Europeans: Studies in Indo-European Comparative Mythology, University of California, ISBN 9780520015876

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel (1964), Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, OCLC 645398380