During the Cold War, the term Third World referred to the developing countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the nations not aligned with either the First World or the Second World.[1][2] This usage has become relatively rare due to the ending of the Cold War.

In the decade following the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War in 1991, the term Third World was used interchangeably with developing countries, but the concept has become outdated as it no longer represents the current political or economic state of the world. The three-world model arose during the Cold War to define countries aligned with NATO (the First World), the Communist Bloc (the Second World, although this term was less used), or neither (the Third World). Strictly speaking, "Third World" was a political, rather than an economic, grouping.

Since about the 2000s the term Third World has been used less and less. It is being replaced with terms such as developing countries, least developed countries or the Global South.

Etymology

French demographer, anthropologist and historian Alfred Sauvy, in an article published in the French magazine L'Observateur, August 14, 1952, coined the term Third World (French: Tiers Monde), referring to countries that were unaligned with either the Communist Soviet bloc or the Capitalist NATO bloc during the Cold War.[3] His usage was a reference to the Third Estate, the commoners of France who, before and during the French Revolution, opposed the clergy and nobles, who composed the First Estate and Second Estate, respectively. Sauvy wrote, "This third world ignored, exploited, despised like the third estate also wants to be something."[4] He conveyed the concept of political non-alignment with either the capitalist or communist bloc.[5]

Origin and shift of meaning

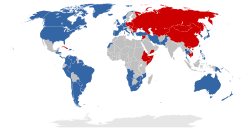

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Communist Bloc. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the First World, while the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, and their allies represented the Second World. This terminology provided a way of broadly categorizing the nations of the Earth into three groups based on political and economic divisions. Since the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the term Third World has been used less and less. It is being replaced with terms such as developing countries, least developed countries or the Global South. The concept itself has become outdated as it no longer represents the current political or economic state of the world.

The Third World was normally seen to include many countries with colonial pasts in Africa, Latin America, Oceania and Asia. It was also sometimes taken as synonymous with countries in the Non-Aligned Movement. In the dependency theory of thinkers like Raúl Prebisch, Walter Rodney, Theotonio dos Santos, and Andre Gunder Frank, the Third World has also been connected to the world-systemic economic division as "periphery" countries dominated by the countries comprising the economic "core".[6]

Due to the complex history of evolving meanings and contexts, there is no clear or agreed-upon definition of the Third World.[6] Some countries in the Communist Bloc, such as Cuba, were often regarded as "third world". Because many Third World countries were economically poor and non-industrialized, it became a stereotype to refer to poor countries as "third world countries", yet the "Third World" term is also often taken to include newly industrialized countries like Brazil, India, and China; they are now more commonly referred to as part of BRIC. Historically, some European countries were non-aligned and a few of these were and are very prosperous, including Ireland, Austria, Sweden, Finland, Switzerland and Yugoslavia.

Third World vs. Three Worlds

The "Three Worlds Theory" developed by Mao Zedong is different from the Western theory of the Three Worlds or Third World. For example, in the Western theory, China and India belong respectively to the Second and Third Worlds, but in Mao's theory both China and India are part of the Third World which he defined as consisting of exploited nations.

The "Three Worlds Theory" developed by Mao Zedong is different from the Western theory of the Three Worlds or Third World. For example, in the Western theory, China and India belong respectively to the Second and Third Worlds, but in Mao's theory both China and India are part of the Third World which he defined as consisting of exploited nations.

For a long time, considerable attention in the international communist movement had been devoted to debating the Chinese international line. Since the counter-revolutionary coup in China shortly after Comrade Mao Zedong’s death, it had become clear that the “three worlds” strategy is part and parcel of the Chinese revisionists’ general line for the restoration of capitalism in China and capitulation to imperialism, particularly at this time U.S. imperialism, on a world scale.

In 1966 Mao wrote to his wife and close comrade, Chiang Ching, that if, after he died the capitalist-roaders came to power, then “The right in power could utilize my words to become mighty for a while. But then the left will be able to utilize others of my words and organize itself to overthrow the right.”

What stands out most sharply is that the “three worlds” theory is not a theory at all, but rather an empty and shallow justification for the Chinese revisionists to pursue a pragmatic policy in international affairs. A policy not based on advancing the interests of world revolution but on the contrary a policy of sacrificing support for revolutionary struggles and based on an overall line of gutting socialism in China itself for what the revisionist usurpers see to be their immediate and narrow interests.

Due to the fact that the “three worlds” strategy is a recipe for capitulation, it has found supporters in many countries throughout the world among precisely those self-styled “Marxists” anxious to grab hold of any justification–especially one backed by a country as prestigious as the People’s Republic of China.

In other countries such as Mozambique or Tanzania, political power does not rest with the out-front spokesmen for imperialism and instead the political task is one of arming the masses with the understanding that the national bourgeoisie is likely to capitulate to imperialism or, failing that, to be crushed by it. The communists must prepare the masses politically, organizationally and militarily to carry the revolution forward to socialism and must consistently build struggle toward that aim. And the “three worlds” theory would even place the “socialist countries” as part of this monolithic “third world.” As to why Mao referred to China as part of the “third world,” more later.

The “three worlds” theory makes the assumption in analysing the “second world” countries that a revolutionary situation does not exist nor can one conceivably arise. Therefore the working class in these countries can do no better than to compete with the bourgeoisie for the position of being the best fighters in preserving the imperialists’ interests.

Despite the liberal use of quotations from Lenin, Stalin and Mao about this basic feature of the struggle against world imperialism by the Chinese revisionists, the “three worlds analysis” goes entirely against this Leninist principle. It exactly negates the national liberation struggles–essentially presenting them as a thing of the past. In place of the struggle for national liberation in the “third world,” which can only have at its heart the struggle for political (i.e., state) power, it substitutes the fight for “economic independence,” led by the reactionary ruling classes.

The “three worlds” strategy postulated that the great majority of “third world” countries have achieved their independence but are still subjected to bullying and encroachments by the superpowers.

Others have argued that the end of the cold War,has dealt the ‘three worlds’ classification scheme a fatal blow, and the break-up of the former Soviet Union and the associated disintegration of the Second World has, to a large extent, diminished the rationale which underlay the concept of the Third World. Furthermore, Third Worldism has been on a path of terminal decline due to a number of factors, such as disproportionate economic development among Third Worldist states, political differences and the failure to establish a “common program for international economic and political reform.Within the literature relating to Third Worldism, the concept of the Third World itself, and the three worlds scheme, there is a lively debate, with some arguing that the concept has become an anachronism, and others maintaining that the concept maintains significance in the contemporary era. Furthermore, while there is general consensus within the literature that Third Worldism has experienced a declining trend, some argue that there is both the need and space for a revival of Third Worldism.

Third Worldism

Third Worldism is a political movement that argues for the unity of third-world nations against first-world and probably second-world influence and the principle of non-interference in other countries' domestic affairs. Groups most notable for expressing and exercising this idea are the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Group of 77 which provide a base for relations and diplomacy between not just the third-world countries, but between the third-world and the first and second worlds. The notion has been criticized as providing a fig leaf for human-rights violations and political repression by dictatorships.[7]

Decline of Third-Worldism and Critiques of the Concept

The 1961 Belgrade Non-Aligned Summit conference established an alternative platform for “negotiating the diplomatic solidarity of countries which saw an advantage in advertising their autonomy from the rival superpower blocs.”The rhetoric, membership and aims of the group of states “represented at the Non-Aligned summits of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s” expanded and contracted considerably as time progressed. During the early stages of the 1960s, primary focus was directed towards mitigating the effects of the Cold War, “as represented by the British and French invasion of the Suez, and the Russian invasion of Hungary in 1956, on states which were not part of any power bloc.Towards the middle of the 1960s, the crucial concern was anti-colonialism, and from the close of that decade through to the next, the principle issues centered on “problems of economic development,” specifically those emerging due to intense uncertainty in the global economy.

The increasing influence of dependency theory, and the claim that the Third World is located in an international political system characterized by a deep-rooted and progressively expanding asymmetry and a causal relationship between the (over)development of some states and the underdevelopment of others, facilitated the legitimization of a “common agenda for changing the structure of international relations – especially of international economic relations – on which that asymmetry seemed to rest.” During the 1970s, the collective identity of the majority of Latin American, Asian and African countries in “international relations became expressed through demands for reform in the institutional structure of the international economy.” The main thrust here came from the Group of 77 (G77), which had been created at the first United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) meeting held in 1964. During the early stages of the 1970s, as “severe external shocks hit the international economy,”the G77 headed the “demand for new institutions of global economic management to remove the structural imbalances that, as they saw it, frustrated the development of countries outside the OECD and Comecon.”

The effectiveness of this campaign was evidenced “by the passing of the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States and the Declaration,”as well as the Declaration of a NIEO at a special session of the UN General Assembly in 1974.The demand for a NIEO was preceded by, and to some extent bolstered by, the 1973 oil crisis; this call was “based on the implementation of 25 objectives”relating to international trade, international assistance and aid, social issues, technology transfer and industrialization. These objectives were to be realised in ways that would guarantee the states’ economic sovereignty, “including their right to control the exploitation of natural resources, with the right to nationalize them of appropriate.” In hindsight, it becomes clear that the UN resolutions passed in 1974 relating to the NIEO signalled the zenith of the diplomatic unity of Third World regimes that had challenged Western hegemony, and in rhetoric that was linked to the “international economic relations of development.”

The changes called for in the NIEO never materialized and were never implemented. As the 1970s drew to a close, the Third World coalition’s ability at the UN to exert influence for change was diminishing as their capacity to employ their primary weapon – “the threat of commodity boycotts for a range of primary products and minerals in the manner of the OPEC manipulation of oil prices” – suffered a loss of credibility. Furthermore, OPEC’s increasing influence had the adverse effect of weakening Third Worldism, rather than strengthening it. The emergence anti-communist, oil-rich, conservative nation states, especially in the Middle East, often with robust ties to the US, represented a significant barrier to the “realisation of the NIEO and the wider Third Worldist project.” The 1980s brought what Mark T. Berger has referred to as the “climacteric of the Third World.” The outbreak of violence between the ‘red brotherhood’ of Cambodia, Vietnam, China and Laos towards the end of the 1970s underlined the evident “failure of socialist internationalism and its close relative, Third Worldism.” In more general terms, by the start of the 1980s, the US-driven globalisation project provided a significant challenge to the importance allocated to the restructuring of the global economy so as to “address the North-South divide.” With the Debt Crisis and world recession in the early stages of the 1980s, the UN backed idea of a NIEO disappeared from the agenda, dislodged by the globalisation project.The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, supported by the Reagan administration, Prime Minister Thatcher in the UK, and Chancellor Kohl in the former West Germany, encouraged Third World governments to undertake the privatisation of public sectors, the liberalisation of trade and the deregulation of financial sectors. This trend intersected with a renewal of hostilities that characterised the Cold War, which further facilitated the decline of the NAM.

A reduction in demand for primary products, “declining terms of trade for their exports, rapidly rising costs of debt repayment and re-borrowing,” internal issues relating to “agricultural productivity and natural disaster” resulted in large scale “economic failure in Africa,” ultimately undermining the legitimacy, vitality and strength of a large number of Third World states.Furthermore, when the curtain came down on the Cold War late in the 1980s, “the removal of the possibility of Soviet support” had a limiting effect on the significance of “existing African governments as allies in the geopolitical war of position between the superpowers,” as well as the ability of Third World states to “conclude favourable bargains for outside assistance.”These shifts had significant effects on the psychological and political ties which held the Third World coalition together, since the UN ceased to be a key platform for the pursuit and achievement of structural reform of the international political economy.

Emerging in the context of the Cold War, the concept of the Third World was employed to various ends: namely as a means to control that which was known as the Third World, but also as a mobilising myth for the successful completion of decolonisation and for the establishment of a counter hegemonic alliance. However, the end of the Cold War and the disintegration of the USSR and the disappearance of the Second World have called into question the relevance of the concept of the Third World, and furthermore, a failure to implement its political economic projects as well as political differences, has led to a decline in Third-Worldism, to an extent where many scholars are questioning the very existence of the Third World. This essay has set out to argue that the concept of the Third World enjoys continued relevance in the contemporary era and has remained alive in both scholarly and public realms well beyond the end of the Cold War. To this end, arguments built around geopolitics, the concept of the Third World as a “reference point for development in global politics,” and Dirlik’s notion of “global modernity” have been employed. This essay also aimed to argue that there is a need for a revival of Third-Worldism in the contemporary era, and here, the main argument focused on the structure of the global political economy and global hegemony, and how this has given rise to a “new exclusionary structure between the Trilateral North and the Tri-Continental South,”which warrants the creation and establishment of a “new counter-hegemonic alliance” based on the Bandung principles – what I have argued for, namely a revival of Third Worldism.

History

Most Third World countries are former colonies. Having gained independence, many of these countries, especially smaller ones, were faced with the challenges of nation- and institution-building on their own for the first time. Due to this common background, many of these nations were "developing" in economic terms for most of the 20th century, and many still are. This term, used today, generally denotes countries that have not developed to the same levels as OECD countries, and are thus in the process of developing.

In the 1980s, economist Peter Bauer offered a competing definition for the term "Third World". He claimed that the attachment of Third World status to a particular country was not based on any stable economic or political criteria, and was a mostly arbitrary process. The large diversity of countries considered part of the Third World — from Indonesia to Afghanistan — ranged widely from economically primitive to economically advanced and from politically non-aligned to Soviet- or Western-leaning. An argument could also be made for how parts of the U.S. are more like the Third World.[8]

The only characteristic that Bauer found common in all Third World countries was that their governments "demand and receive Western aid," the giving of which he strongly opposed. Thus, the aggregate term "Third World" was challenged as misleading even during the Cold War period, because it had no consistent or collective identity among the countries it supposedly encompassed.

Development aid

During the Cold War, unaligned countries of the Third World[6] were seen as potential allies by both the First and Second World. Therefore, the United States and the Soviet Union went to great lengths to establish connections in these countries by offering economic and military support to gain strategically located alliances (e.g. the United States in Vietnam or the Soviet Union in Cuba).[6] By the end of the Cold War, many Third World countries had adopted capitalist or communist economic models and continued to receive support from the side they had chosen. Throughout the Cold War and beyond, the countries of the Third World have been the priority recipients of Western foreign aid and the focus of economic development through mainstream theories such as modernization theory and dependency theory.[6]

By the end of the 1960s, the idea of the Third World came to represent countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America that were considered underdeveloped by the West based on a variety of characteristics (low economic development, low life expectancy, high rates of poverty and disease, etc.).[3] These countries became the targets for aid and support from governments, NGOs and individuals from wealthier nations. One popular model, known as Rostow's stages of growth, argued that development took place in 5 stages (Traditional Society; Pre-conditions for Take-off; Take-off; Drive to Maturity; Age of High Mass Consumption).[9] W. W. Rostow argued that Take-off was the critical stage that the Third World was missing or struggling with. Thus, foreign aid was needed to help kick-start industrialization and economic growth in these countries.[9]

Great Divergence and Great Convergence

Density function of the world's income distribution in 2015 by continent, logarithmic scale: The division of the world into "rich" and "poor" was vanished, and the world's poverty can be found mainly in Africa.

Many times there is a clear distinction between First and Third Worlds. When talking about the Global North and the Global South, the majority of the time the two go hand in hand. People refer to the two as "Third World/South" and "First World/North" because the Global North is more affluent and developed, whereas the Global South is less developed and often poorer.[10]

To counter this mode of thought, some scholars began proposing the idea of a change in world dynamics that began in the late 1980s, and termed it the Great Convergence.[11] As Jack A. Goldstone and his colleagues put it, "in the twentieth century, the Great Divergence peaked before the First World War and continued until the early 1970s, then, after two decades of indeterminate fluctuations, in the late 1980s it was replaced by the Great Convergence as the majority of Third World countries reached economic growth rates significantly higher than those in most First World countries".[12]

Others have observed a return to Cold War-era alignments (MacKinnon, 2007; Lucas, 2008), this time with substantial changes between 1990–2015 in geography, the world economy and relationship dynamics between current and emerging world powers; not necessarily redefining the classic meaning of First, Second, and Third World terms, but rather which countries belong to them by way of association to which world power or coalition of countries — such as the G7, the European Union, OECD; G20, OPEC, BRICS, ASEAN, the African Union, and the Eurasian Union.

See also

References

=