This is a sandbox for my work on chromosome wiki page

A chromosome is an organized structure of DNA and protein that is found in cells. It is a single, continuous molecule of double-stranded DNA containing many genes, regulatory elements, and other nucleotide sequences. In cells, chromosomal DNA is not "naked"; rather, it is wrapped around DNA-binding proteins known as histones which serve to package the DNA and control its functions. A cell may contain many chromosomes, with the collection of all the chromosomes in a cell known as the genome. The word chromosome comes from the Greek χρῶμα (chroma, color) and σῶμα (soma, body) due to their property of being very strongly stained by particular dyes.

Chromosomes vary widely between different organisms, with the most striking differences observed between prokaryotes (organisms lacking cell nuclei) and eukaryotes (cells containing nuclei). The DNA molecule may be circular or linear, and can be composed of 10,000 to 1,000,000,000[1] nucleotides in a long chain. Typically eukaryotic cells (cells with nuclei) have large linear chromosomes and prokaryotic cells (cells without defined nuclei) have smaller circular chromosomes, although there are many exceptions to this rule. Furthermore, cells may contain more than one type of chromosome; for example, mitochondria in most eukaryotes and chloroplasts in plants have their own small chromosomes.

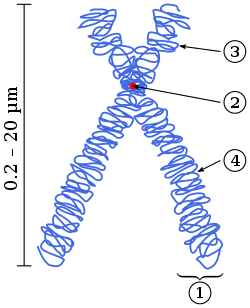

In eukaryotes, nuclear chromosomes are packaged by proteins into a condensed structure called chromatin. This allows the very long DNA molecules to fit into the cell nucleus. The structure of chromosomes and chromatin varies through the cell cycle. Chromosomes are the essential unit for cellular division and must be replicated, divided, and passed successfully to their daughter cells so as to ensure the genetic diversity and survival of their progeny. Chromosomes may exist as either duplicated or unduplicated—unduplicated chromosomes are single linear strands, whereas duplicated chromosomes (copied during synthesis phase) contain two copies joined by a centromere. Compaction of the duplicated chromosomes during mitosis and meiosis results in the classic four-arm structure (pictured to the right). Chromosomal recombination plays a vital role in genetic diversity. If these structures are manipulated incorrectly, through processes known as chromosomal instability and translocation, the cell may undergo mitotic catastrophe and die, or it may aberrantly evade apoptosis leading to the progression of cancer.

In practice "chromosome" is a rather loosely defined term. In prokaryotes and viruses, the term genophore is more appropriate when no chromatin is present. However, a large body of work uses the term chromosome regardless of chromatin content. In prokaryotes DNA is usually arranged as a circle, which is tightly coiled in on itself, sometimes accompanied by one or more smaller, circular DNA molecules called plasmids. These small circular genomes are also found in mitochondria and chloroplasts, reflecting their bacterial origins. The simplest genophores are found in viruses: these DNA or RNA molecules are short linear or circular genophores that often lack structural proteins.

History

Identification of Chromosomes

The idea that the hereditary information of a cell was contained within the nucleus originated within Ernst Haeckel's Generelle Morphologie of 1866.[2] While insightful, at the time Haeckel's notion lacked supporting scientific data. The first direct observation of chromosomes was achieved in 1879 by Walter Flemming, who used microscopy to observe mitosis (cell division)in salamander tail cells. Using dyes to aid in observing mitosis, he took note of strongly stained thread-like structures he coined chromatin. A colleague of Flemming, Heinrich Wilhelm Gottfried von Waldeyer-Hartz later renamed the stained structures chromosomes.

The evidence for this insight gradually accumulated until, after twenty or so years, two of the greatest in a line of great German scientists[citation needed] spelled out the concept. August Weismann proposed that the germ line is separate from the soma, and that the cell nucleus is the repository of the hereditary material, which, he proposed, is arranged along the chromosomes in a linear manner. Further, he proposed that at fertilisation a new combination of chromosomes (and their hereditary material) would be formed. This was the explanation for the reduction division of meiosis (first described by van Beneden).

Chromosomes as Vectors of Inheritance

In 1902, Theodor Boveri demonstrated through a series of experiments using sea urchin sperm and egg cells the following three properties of chromosomes:

- That the nucleus is the cellular component responsible for heredity

- That chromosomes are likely the vectors of heredity

- That each chromosome contains a unique set of hereditary information necessary for proper cell development

It is worthy to note that the third property Boveri identified was possible due to chromosomes having distinct morphologies under a microscope.

It is the second of these principles that was so original[citation needed]. Boveri was able to test the proposal put forward by Wilhelm Roux, that each chromosome carries a different genetic load, and showed that Roux was right. Upon the rediscovery of Mendel, Boveri was able to point out the connection between the rules of inheritance and the behaviour of the chromosomes. It is interesting to see that Boveri influenced two generations of American cytologists: Edmund Beecher Wilson, Walter Sutton and Theophilus Painter were all influenced by Boveri (Wilson and Painter actually worked with him).

In his famous textbook The Cell, Wilson linked Boveri and Sutton together by the Boveri-Sutton theory. Mayr remarks that the theory was hotly contested by some famous geneticists: William Bateson, Wilhelm Johannsen, Richard Goldschmidt and T.H. Morgan, all of a rather dogmatic turn-of-mind. Eventually complete proof came from chromosome maps in Morgan's own lab.[3]

Chromosomes in Prokaryotes

The prokaryotes – bacteria and archaea – typically have a single circular chromosome, but many variations do exist.[4] Most bacteria have a single circular chromosome that can range in size from only 160,000 base pairs in the endosymbiotic bacterium Candidatus Carsonella ruddii,[5] to 12,200,000 base pairs in the soil-dwelling bacterium Sorangium cellulosum.[6] Spirochaetes of the genus Borrelia are a notable exception to this arrangement, with bacteria such as Borrelia burgdorferi, the cause of Lyme disease, containing a single linear chromosome.[7]

Structure in sequences

Prokaryotic chromosomes have less sequence-based structure than eukaryotes. Bacteria typically have a single point (the origin of replication) from which replication starts, whereas some archaea contain multiple replication origins.[8] The genes in prokaryotes are often organized in operons, and do not usually contain introns, unlike eukaryotes.

DNA packaging

Prokaryotes do not possess nuclei. Instead, their DNA is organized into a structure called the nucleoid.[9] The nucleoid is a distinct structure and occupies a defined region of the bacterial cell. This structure is, however, dynamic and is maintained and remodeled by the actions of a range of histone-like proteins, which associate with the bacterial chromosome.[10] In archaea, the DNA in chromosomes is even more organized, with the DNA packaged within structures similar to eukaryotic nucleosomes.[11][12]

Bacterial chromosomes tend to be tethered to the plasma membrane of the bacteria. In molecular biology application, this allows for its isolation from plasmid DNA by centrifugation of lysed bacteria and pelleting of the membranes (and the attached DNA).

Prokaryotic chromosomes and plasmids are, like eukaryotic DNA, generally supercoiled. The DNA must first be released into its relaxed state for access for transcription, regulation, and replication.

Chromosomes in Eukaryotes

(tag removed) mergefrom|Eukaryotic chromosome fine structure|date=December 2007}}Eukaryotes (cells with nuclei such as those found in plants, yeast, and animals) possess multiple large linear chromosomes contained in the cell's nucleus. Each chromosome has one centromere, with one or two arms projecting from the centromere, although, under most circumstances, these arms are not visible as such. In addition, most eukaryotes have a small circular mitochondrial genome, and some eukaryotes may have additional small circular or linear cytoplasmic chromosomes. The ends of the linear chromosome arms contain highly condensed, repetitive DNA sequences known as telomeres.

In the nuclear chromosomes of eukaryotes, the uncondensed or "naked" DNA is packaged by being wrapped around globular proteins called histones (structural proteins), forming a composite structure known as a nucleosome. Each nucleosome consists 147 base-pairs of double-stranded DNA wrapped around a single histone protein. The general term for DNA bound by packaging proteins is chromatin.

Chromatin

Chromatin is the complex of DNA and protein found in the eukaryotic nucleus, which packages chromosomes. The structure of chromatin varies significantly between different stages of the cell cycle, according to the requirements of the DNA. Chromatin should be distinguished from DNA which is "naked", or unpackaged by DNA-packaging proteins such as histones.

Chromatin in eukaryotic cells can be found in two general states:

- Euchromatin, which consists of DNA that is loosely packaged and tends to contain actively expressed genes.

- Heterochromatin, which consists of mostly inactive (non-expressed) DNA and is more highly compacted than euchromatin. Heterochromatin can be further distinguished into two types:

- Constitutive heterochromatin, which is never expressed. It is located around the centromere and usually contains repetitive sequences. Constituitive heterochromatin is also associated with silencing of mobile DNA elements such as transposons.

- Facultative heterochromatin, which is sometimes expressed. Facultative heterochromatin is often used to regulate the expression of genes in differentiated cells (for example, a muscle cell would prevent expression of genes which regulate neuron-specific processes).

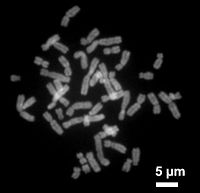

Individual chromosomes cannot be visually distinguished in interphase without the use of dyes or molecular labels – they appear in the nucleus as a homogeneous tangled mix of DNA and protein.

Metaphase chromatin and division

In the early stages of mitosis or meiosis (cell division), the chromatin strands become more and more condensed. They cease to function as accessible genetic material (transcription stops) and become a compact transportable form. This compact form makes the individual chromosomes visible, and they form the classic four arm structure, a pair of sister chromatids attached to each other at the centromere. The shorter arms are called p arms (from the French petit, small) and the longer arms are called q arms (q follows p in the Latin alphabet). This is the only natural context in which individual chromosomes are visible with an optical microscope.

During divisions, long microtubules attach to the centromere and the two opposite ends of the cell. The microtubules then pull the chromatids apart, so that each daughter cell inherits one set of chromatids. Once the cells have divided, the chromatids are uncoiled and can function again as chromatin. In spite of their appearance, chromosomes are structurally highly condensed, which enables these giant DNA structures to be contained within a cell nucleus (Fig. 2).

The self-assembled microtubules form the spindle, which attaches to chromosomes at specialized structures called kinetochores, one of which is present on each sister chromatid. A special DNA base sequence in the region of the kinetochores provides, along with special proteins, longer-lasting attachment in this region.

Behavior in Cell Cycle

Mitosis

Meiosis

= Homologous Recombination

Sex Determination

Worms XX/X0

Insects XX/XY but determined by amount of X

Birds ZZ/ZW

Mammals XX/XY determined by Y (SRY)

X-inactivation

Genomes

Ploidy

C-value Paradox

Human Genetics

Human Genome

Diseases

Relationship to Cancer

Number of chromosomes in various organisms

Eukaryotes

These tables give the total number of chromosomes (including sex chromosomes) in a cell nucleus. For example, human cells are diploid and have 22 different types of autosome, each present as two copies, and two sex chromosomes. This gives 46 chromosomes in total. Other organisms have more than two copies of their chromosomes, such as bread wheat, which is hexaploid and has six copies of seven different chromosomes – 42 chromosomes in total.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

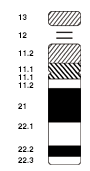

Normal members of a particular eukaryotic species all have the same number of nuclear chromosomes (see the table). Other eukaryotic chromosomes, i.e., mitochondrial and plasmid-like small chromosomes, are much more variable in number, and there may be thousands of copies per cell.  Asexually reproducing species have one set of chromosomes, which are the same in all body cells. However, asexual species can be either haploid or diploid. Sexually reproducing species have somatic cells (body cells), which are diploid [2n] having two sets of chromosomes, one from the mother and one from the father. Gametes, reproductive cells, are haploid [n]: They have one set of chromosomes. Gametes are produced by meiosis of a diploid germ line cell. During meiosis, the matching chromosomes of father and mother can exchange small parts of themselves (crossover), and thus create new chromosomes that are not inherited solely from either parent. When a male and a female gamete merge (fertilization), a new diploid organism is formed. Some animal and plant species are polyploid [Xn]: They have more than two sets of homologous chromosomes. Plants important in agriculture such as tobacco or wheat are often polyploid, compared to their ancestral species. Wheat has a haploid number of seven chromosomes, still seen in some cultivars as well as the wild progenitors. The more-common pasta and bread wheats are polyploid, having 28 (tetraploid) and 42 (hexaploid) chromosomes, compared to the 14 (diploid) chromosomes in the wild wheat.[37] ProkaryotesProkaryote species generally have one copy of each major chromosome, but most cells can easily survive with multiple copies.[38] For example, Buchnera, a symbiont of aphids has multiple copies of its chromosome, ranging from 10–400 copies per cell.[39] However, in some large bacteria, such as Epulopiscium fishelsoni up to 100,000 copies of the chromosome can be present.[40] Plasmids and plasmid-like small chromosomes are, as in eukaryotes, very variable in copy number. The number of plasmids in the cell is almost entirely determined by the rate of division of the plasmid – fast division causes high copy number, and vice versa. Karyotype In general, the karyotype is the characteristic chromosome complement of a eukaryote species.[41] The preparation and study of karyotypes is part of cytogenetics. Although the replication and transcription of DNA is highly standardized in eukaryotes, the same cannot be said for their karyotypes, which are often highly variable. There may be variation between species in chromosome number and in detailed organization. In some cases, there is significant variation within species. Often there is 1. variation between the two sexes; 2. variation between the germ-line and soma (between gametes and the rest of the body); 3. variation between members of a population, due to balanced genetic polymorphism; 4. geographical variation between races; 5. mosaics or otherwise abnormal individuals. Also, variation in karyotype may occur during development from the fertilised egg. The technique of determining the karyotype is usually called karyotyping. Cells can be locked part-way through division (in metaphase) in vitro (in a reaction vial) with colchicine. These cells are then stained, photographed, and arranged into a karyogram, with the set of chromosomes arranged, autosomes in order of length, and sex chromosomes (here X/Y) at the end: Fig. 3. Like many sexually reproducing species, humans have special gonosomes (sex chromosomes, in contrast to autosomes). These are XX in females and XY in males. Historical noteInvestigation into the human karyotype took many years to settle the most basic question. How many chromosomes does a normal diploid human cell contain? In 1912, Hans von Winiwarter reported 47 chromosomes in spermatogonia and 48 in oogonia, concluding an XX/XO sex determination mechanism.[42] Painter in 1922 was not certain whether the diploid number of man is 46 or 48, at first favouring 46.[43] He revised his opinion later from 46 to 48, and he correctly insisted on man's having an XX/XY system.[44] New techniques were needed to definitively solve the problem:

It took until the mid-1950s for it to become generally accepted that the human karyotype include only 46 chromosomes. Considering the techniques of Winiwarter and Painter, their results were quite remarkable.[45][46] Chimpanzees (the closest living relatives to modern humans) have 48 chromosomes. Chromosomal aberrations   Chromosomal aberrations are disruptions in the normal chromosomal content of a cell, and are a major cause of genetic conditions in humans, such as Down syndrome. Some chromosome abnormalities do not cause disease in carriers, such as translocations, or chromosomal inversions, although they may lead to a higher chance of birthing a child with a chromosome disorder. Abnormal numbers of chromosomes or chromosome sets, aneuploidy, may be lethal or give rise to genetic disorders. Genetic counseling is offered for families that may carry a chromosome rearrangement. The gain or loss of DNA from chromosomes can lead to a variety of genetic disorders. Human examples include:

Chromosomal mutations produce changes in whole chromosomes (more than one gene) or in the number of chromosomes present.

Most mutations are neutral – have little or no effect.Chromosomal aberrations are the changes in the structure of chromosomes.It has a great role in evolution.A detailed graphical display of all human chromosomes and the diseases annotated at the correct spot may be found at[49]. Human chromosomesChromosomes can be divided into two types--autosomes, and sex chromosomes. Certain genetic traits are linked to your sex, and are passed on through the sex chromosomes. The autosomes contain the rest of the genetic hereditary information. All act in the same way during cell division. Human cells have 23 pairs of large linear nuclear chromosomes, (22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes) giving a total of 46 per cell. In addition to these, human cells have many hundreds of copies of the mitochondrial genome. Sequencing of the human genome has provided a great deal of information about each of the chromosomes. Below is a table compiling statistics for the chromosomes, based on the Sanger Institute's human genome information in the Vertebrate Genome Annotation (VEGA) database.[50] Number of genes is an estimate as it is in part based on gene predictions. Total chromosome length is an estimate as well, based on the estimated size of unsequenced heterochromatin regions.

See also

External links Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chromosomes.

References | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||