The Westminster Retable, the oldest known panel painting altarpiece in England,[1] is estimated to have been painted in the 1270s in the circle of Plantagenet court painters, for Westminster Abbey, very probably for the high altar.[2] It is thought to have been donated by Henry III of England as part of his Gothic redesign of the Abbey.[3] The painting survived only because it was incorporated into furniture between the 16th and 19th centuries, and much of it has been damaged beyond restoration. According to one specialist, the "Westminster Retable, for all its wounded condition, is the finest panel painting of its time in Western Europe."[4]

In 1998 the Hamilton Kerr Institute in Cambridge, with support from the Getty Foundation and the National Heritage Lottery Fund, began a six-year project to clean and conserve what remained of the work. Upon completion, it was displayed at the National Gallery in London for four months in 2005 before being returned to Westminster Abbey,[5] where it is displayed in the Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries in the Abbey's triforium.[2]

Description

The retable measures 959 x 3330 mm (approximately 3 feet by 11 feet) and is painted on several joined oak panels using thin glazes of colour in linseed oil on a gesso ground.[2] The construction is complex, with six main flat panels, and several other wooden elements.[1] The retable is divided into five sections by gilded wooden arcading,[6] with pastiglia relief work, elaborate glass inlays, inset semi-precious stones and paste gemstones, to imitate the lavish goldsmith's metalwork found on some surviving retables and shrines on the Continent, and the now destroyed Shrine of Edward the Confessor installed in the Abbey in 1269.[7]

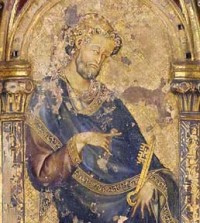

The composition has a central section with three tall narrow openings defined by tracery containing full-length figures of Christ holding a globe as Salvator Mundi, flanked by the Virgin Mary holding a palm, and St John the Evangelist. To the sides are two sections each with four small medallions containing depictions of the Miracles of Christ, those to the right missing completely and those to the left showing the raising of Jairus’ daughter, the healing of the blind man, the feeding of the 5,000 and another subject, too defaced to identify. The outermost sections contained single figures, to the left St Peter, dedicatee of the Abbey and the best preserved single figure, with the figure to the right now missing completely; according to George Vertue this was St. Paul.[8] These sidemost panels were evidently added when most of the retable had been completed, and are of German rather than local Thames Valley oak, and the grain runs vertically, rather than horizontally as on the four panels making up the central three sections. The back of the retable, which would have been invisible, is painted as imitation porphyry.[1] Much of the retable is lost beyond recovery.

The painting is of very high quality, probably by an artist used to working on illuminated manuscripts, to judge by the fine detail of the work, and some stylistic details. In its position on the high altar the detailed images would only have been clearly visible to officiating clergy, and no concessions were made to more popular taste.[10] The tiny globe held by Christ is painted with four registers of scenes showing animals, trees, and a man in a boat.[9]

History

After the Benedictine abbey was dissolved in 1540, the retable panel was made into the lid of a chest, with the main painted side facing down, that was used to store wax funeral effigies of English monarchs.[1] In the eighteenth century, the two right hand panels had their medieval paint removed and covered in grey and white paint. The Retable was discovered by George Vertue in 1725, but in 1778 serious damage was caused when the chest was modified into a cupboard or display case to show the funeral effigy of Pitt the Elder.[11]

In 1827, the Retable was seen by the architect Edward Blore, then Surveyor of the Abbey, and his rediscovery was published in The Gentleman's Magazine.[12] Blore had the Retable removed from the chest and set in a glazed frame.[13] Since its rediscovery, the piece has been further damaged by attempted restoration efforts, which included a coating of glue intended to hold together painted layers.[14] In 1858, watercolours of the Retable were made for the Society of Antiquaries of London; a conjectural restoration was included in Viollet-le-Duc's Dictionnaire raisonné du mobilier français,[15] and plates accompanied William Burges's essays, published in 1863, on painted objects at Westminster Abbey.[16] The first photographs of the Retable were published in 1897.[17]

It is currently housed in a glass frame to protect it from further deterioration. From 1827 to 1902, the Retable was kept in the Jerusalem Chamber, before being moved to the south ambulatory. It was later displayed in the Westminster Abbey Museum, along with Pitt and the other wax effigies, until the museum closed for redevelopment.[18] Since 2018, the Retable has been on display in the Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries in the abbey's triforium.[2]

Notes

References

- Tudor-Craig, Pamela, in: Wilson, Christopher and others: Westminster Abbey, Bell and Hyman, London, 1986, ISBN 978-0-7135-2613-4

Further reading

- Binski, Paul ; Ann Massing (eds); The Westminster Retable: History, Technique, Conservation, Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2008, ISBN 978-1-905375-28-8

- Macek, Pearson Marvin. 'The discoveries of the Westminster Retable, 'Archaeologia, 109 (1991), 101–11. Publisher: Society of Antiquaries of London. ISSN 0261-3409 (and his unpublished thesis at Michigan Univ, Ann Arbor, 1986)