Zichan (WG: Tzu Ch'an) (traditional Chinese: 子產; simplified Chinese: 子产)[1] (c.581-522) was a Chinese statesman during the late Spring and Autumn period. From 543 until his death in 522 BCE, he served as the chief minister of the State of Zheng. Also known as Gongsun Qiao (traditional Chinese: 公孫僑; simplified Chinese: 公孙侨,[2] he is better known by his courtesy name Zichan.

As chief minister of Zheng, a notable and centrally-located state, Zichan faced aggression from powerful neighbors without and a fractious domestic politics within. He led as Chinese culture and society endured a centuries-long period of turbulence. Governing traditions were then unstable and malleable, institutions battered by chronic war, and emerging new ways of government sharply contested.

Under Zichan the Zheng state prospered. He introduced strengthening reforms and met foreign threats. His statecraft was respected by his peers and reportedly appreciated by the people. Favorably treated in the Zuo Zhuan (an ancient text of history), Zichan drew comments from his near-contemporary Confucius, later from Mencius and Han Fei.

Background

Zhou dynasty

By its military defeat in 771 BCE, later historians divide the Zhou (c.1045-221) into periods: Western and Eastern, as in retreat Zhou moved its capital over 500 km. east.[3][4] The dynasty not only never recovered, it steadily lost strength during the Spring and Autumn period (770-481). At its start the Zhou government used the fengjian system. Differing from the feudal, kinship formed the primary bond between the royal dynast and local 'vassal'.[5][6][7][8]

State of Zheng

The founder of Zheng was Duke Huan (r.806-771), brother to Zhou King Xuan (r.825-782). Zheng state by 767 had also moved its capital east, adjacent to Zhou's new royal lands.[9][10][11][12] Strategically located, Zheng prospered by trade.[13] In 707 Duke Zhuang of Zheng (r.743-701) defeated the Zhou King's invasion. This celebrated Duke is compared to the Five Hegemons. In 673 Zheng attacked the royal capital, killed the usurping ruler, and restored the prior Zhou King. Although Zheng's military then declined, it prospered, and survived many attacks by powerful neighbors.[14][15] In Zheng later during the Warring States (480-221) "the centre of the political stage was occupied by the competition between clans".[16] During that era's fierce interstate combat, Zheng met its demise in 375 BCE.[17][18][19][20][21]

Family of Zichan

Zichan was closely related to the hereditary Dukes of Zheng state, hence also kin of the royal Zhou. As a grandson of Zheng's admired Duke Mu (r. 627-606), he was called Gongsun Qiao, "Ducal Grandson". Zichan was a member of the clan of Guo, one of the Seven Houses of Zheng. These clans led by nobility competed for power; yet the Guo was seldom the strongest. His ancestral surname was Ji,[22] his personal name was Ji Qiao.[23][24][25]

In 565 BCE Zichan's father, Prince Fa (Gongzi Fa), led a victorious campaign against the State of Cai. His military success, however, risked provoking the hostility of stronger neighboring states, e.g., Chu to the south and Jin to the north. Yet the Zheng leadership appeared pleased. Except Zichan, said a small state like Zheng should excel in civic virtue, not martial achievement, else it will have no peace. Prince Fa (Ziguo) then harshly rebuked his teenage son Zichan.[26][27][28][29] Shortly after the Cai victory, but unrelated, Prince Fa was assassinated by rival nobles of Zheng.[30][31] Amid internal power struggles, Duke Jian of Zheng (r. 566-530) had begun his reign.[32]

Career profile

Path as state official

In 543 BCE, when nearing 40 years of age,[33][34] Zichan became prime minister of Zheng state. Zichan's career path to the top position started in 565,[35] and involved his finding a way through the unexpected sometimes violent events and social instabilities that challenged Zheng's political class. Selected events of his early career follow, the chief primary source being the Zuo Zhuan.[36][37]

Since 570 BCE Zichan's father had been one of three leading aristocrats who directed Zheng's government. The head of state was the Duke of Zheng, but in fact this triumvirate of nobles kept control. In 562 BCE "armed insurgents" led by seven disaffected clan nobles, overthrew the government and killed all three rulers. Zichan survived, and rallied his clan. He "got all his officers in readiness... formed his men in ranks, [and] went forth with 17 chariots of war." Another "led the people" to Zichan's side. Two rebel leaders (and many followers) were killed; five fled Zheng.[38][39] The ruling 'oligarchy' of elite nobles prevailed, the brutal tactics of the uprising failed.[40][41]

Zikong, the new Zheng leader after the failed 562 rebellion, prepared and issued a document declaring his autocratic rule. It provoked fierce opposition from the nobility and the people. Zichan urged Zikong to renounce the document by burning it in public. His rhetoric to Zikong used likely scenarios to illustrate a probable negative outcome. Zikong then burned it.[42][43][44] In 553 BCE Zikong tried again to monopolize political power, supported by Chu state. But two nobles rose to fatally block him. The two formed a new triumvirate to rule Zheng, the third being Zichan, elevated now as a high minister.[45][46][47]

Zheng state in 561 BCE had joined a coalition headed by the powerful Jin state to the north.[48] Zichan as a high minister maneuvered to ally Zheng with the other small-state members, in order to lighten their burdens. The hedgemon Jin had required all 'northern league' members to make regular state visits to Jin, and each time to bring high-value gifts.[49][50] In 548 Zichan wrote a convincing letter to Jin's chief minister. It criticized Jin for increasing the value of 'gifts' demanded. Zichan argued this worked against Jin's reputation. Worth more than the gifts was Jin's good name; on it rested Jin's virtue, the very foundation of Jin state.[51][52][53] Zichan continued to lobby Jin on behalf of the small states.[54]

In 547 BCE the Zheng people made war on the small state of Chen as pay back (a year earlier Chu state and Chen attacked Zheng,[55] closing up wells and cutting down trees). With 700 chariots Zheng took the Chen capital. Yet Zichan directed military leaders to return without looting the city or destroying its sanctuaries; nor did the Zheng army seize hostages. For a military victor to act harshly, take war booty and vengeance was then customary in ancient China's multistate system.[56][57][58][59][60] Zichan later defended Zheng's invasion of Chen to Jin's ministers.[61][62][63]

A violent feud broke out between several elite nobles of rival clans. It threatened the unity of Zheng state. Initially Zichan had distanced himself to avoid the bitter conflict's social contagion. Yet his attention was solicited. By using the remedial details from a local tradition,[64][65][66][67][68] as a guide, Zichan managed to bring the raucous disputants into negotiation, circa 543 BCE. The solution worked-out did not prove agreeable to all the parties, yet the bloody feud came to an end.[69][70][71][72]

Zichan had remained a popular leader.[73][74] Zheng's chief minister in 544 wanted to appoint Zichan as his successor. Zichan declined: the office was burdened from without by strong and aggressive rival states, and from within by constant feuding of the clans. In the end, Zichan was convincingly assured of a tolerable coexistence among the nobility. Such unity might be sufficient for Zichan to pursue reforms.[75][76][77][78]

Reform programs

Zichan initiated actions to strengthen the Zheng state. Along with subordinate ministers and aides,[79] Zichan had strategized what reforms might work best over time, and improvised.

Agricultural methods were managed to increase the harvest. He reset boundaries between farmlands. Tax reforms increased state revenue. Military policies were kept current. Laws were published in a break with tradition. Administration of state operations were centralized, effective officials recruited, social norms guided. Commerce flourished. Rites were performed and Zhou-era customs followed, in an evolving social context.[80] Divinations for Zheng state were handled by its special ministry. Interstate relations required constant vigilance, e.g., to meet demands for tribute. His negotiating skills were tested. Zichan had opposition and acquired a sophist enemy. He did not always succeed.[81] [82]

From the Han dynasty historian Sima Qian,[83] his Shiji:

Tzu-ch'an[84] was one of the high ministers of the state of [Zheng]. ... [Its affairs had been] in confusion, superiors and inferiors were at odds with each other, and fathers and sons quarreled. ... [Then] Tzu-ch'an [was] appointed prime minister. After... one year, the children in the state had ceased their naughty behavior, grey-haired elders were no longer seen carrying heavy burdens... . After two years, no one overcharged in the markets. After three years, people stopped locking their gates at night... . After four years, people did not bother to take home their farm tools when the day's work was finished, and after five years, no more conscription orders were sent out to the knights. ... Tzu-ch'an ruled for twenty-six years [sic], and when he died the young men wept and the old men cried... .[85][86][87]

The earlier Zuo Zhuan had also told of the people's appraisal of Zichan, a version similar to the Shiji, but differing in stages and detail. After one year the workers complained, griping about new taxes on their clothes and about a new levy against the land. Yet after three years the workers praised Zichan: for teaching their children, and increasing the yield of their fields.[88][89]

Yet however skillful his statecraft, Zichan in his reformist role as proponent of advanced policies was not unique. Over a century earlier Guan Zhong (720-645), the chief minister of Qi, earned praise for his effective management. His innovations included administrative and military-agricultural innovations. The Qi state nonetheless maintained traditional Zhou rituals. As a consequence Duke Huan of Qi became the 'first' of the Five Hegemons, and a noted "paragon".[90][91][92] Another reformist minister was Li Kui (455-395) of Wei.[93][94]

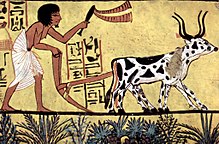

Agriculture

Zichan's policy sought to improve food production, the planting, tending, and harvesting of crops, the care of livestock.[96][97] A minister's role included agricultural management to further state prosperity,[98] as recorded in the Zhou era's Shijing.[99][100][101][102] Techniques and methods developed. Farm implements of stone or wood were being replaced by iron. As yoked to oxen, a metal plow increased the yield, directly causing a rise in prosperity of people and rulers.[103][104][105]

Zichan in 543 BCE reset the boundaries of farm lands and the location of irrigation ditches.[106] "The fields were all marked out by their banks and ditches."[107][108] The Mencius later described a traditional well-field system of land use,[109][110] in which eight plots of farm land surround a ninth to be tilled in common.[111][112] More probably clan lineages (zu) controlled the agricultural lands, and distributed parcels to the peasants who paid rent in kind; the remaining land was collectively cultivated to support the lineage temple.[113][114]

The 543 order by Zichan transformed Zheng agriculture, it "carried out such reforms as grouping houses by five, responsible for one another, and marking out all the fields by banks and ditches."[115][116][117] Clan leaders of Zheng had long dominated farming operations on their lands.[118][119] Moving the ditches was inherently risky for any politician. Clans in fierce rivalry had led violent protests to nullify any action to lessen their land dominance, the source of power, wealth, and status.[120][121][122]

Tax issues arose from Zichan's reforms of farmland. Zheng's revenues were chronically short, often due to costs for defense, or to pay out tribute to powerful neighboring states.[123] A 537 BCE reform made by Zichan increased the land tax, which drew sharp criticism in Zheng. The people reviled him, "His father died on the road, and he himself is a scorpion's tail." Zichan replied that there was no harm in the people's complaints, but that the new law benefitted Zheng. "I will either live or die," he said, quoting an Ode, "I will not change it."[124][125]

Taxing land was delicate. Complicated by the multifaceted politics of land ownership, such issues were contested then, and later by scholars.[126] Happening was a fundamental shift in the evolution of land ownership and its agency, starting confusedly in the Spring and Autumn (Zichan's era), and completed more-or-less during the Warring States. Moving away from traditional communities dominated by clan lineages, land ownership devolved, inch by inch, to more efficiently-run holdings of "nuclear family households". Holdings that were taxed.[127][128][129][130] Holdings that were taxed.[131]

Warfare intersected agriculture. Chariots driven in battle by aristocrats (familiar to Zichan) were starting to be supplanted by infantry.[132][133] Most foot soldiers were also farmers.[134][135][136] Interstate military competition was raw, and intensified; pushing ruling ministers to increase their armies, existential demands that drew on agriculture, the chief source of communal wealth and recruits for armed force.[137][138]

Armies were supported by taxing land and put together by drafting farmers. The early reforms by Qi state (7th century BCE) had so organized its infantry fighting units of five as to match the social units of five among the farming families.[139] By his land and land tax reforms starting in 543 BCE, "Zi Chan reordered the fields of Zheng into a grid with irrigation channels, levied a tax on land, organized rural households into units of five, and created a qiu levy."[140][141][142] The qiu levy here suggests the qiu troops of Lu state created circa 590 BCE. Prof. Lewis concludes that Zichan followed the land tax and defense policies of Jin and Lu states in "extending military recruitment into the countryside", strongly opposed by the capital elites who accordingly were "losing their privilege position" as Zheng's armed force.[143][144][145]

As Zhou vassal states developed under their local urban rulers, eventually the people began to identify more with the fruitfulness and vitality of the farm lands, rather than with the fading charisma of the capital aristocrats. This contributed to the decline in status of the urban shrines of Zhou lineage. Countryside "altars of soil and grain" became increasingly popular, multiplied, accumulated meaning.[146][147][148]

In the hierarchy of Zichan's day, the nobility dominated a much larger rural population based on agriculture.[149][150][151] Yet it was a time when the people were becoming more of a political factor that the elites had to somehow acknowledge.[152][153][154] Zichan had earned an early reputation as a civic provider for the people's welfare.[155][156][157] In his leadership style Zichan was advanced, in that he reportedly took into account the views or motivations of the nascent soldier-peasants, the common people of Zheng.[158][159][160]

The laws of 536 BC

Context of legal act

In Zichan's reform of government one major focus concerned the law. Before Zichan, in each state the powerful hereditary clans, descendants of the Zhou lineage, had generally enforced their own closely-held laws and regulations.[161] The contents of the law might be known only to a "limited number of dignitaries who were concerned with their execution and enforcement." Laws "were not made known to the public."[162] "When the people were kept from knowing the law, the ruling class could manipulate it as it saw fit."[163] Yet the traditional governance among the city-states was then faltering and dissolving in continually changing conditions. In many regimes the ministers, by maneuver or ursupation, were replacing Zhou-lineage clan rulers in whose name they had acted. The ministers began to assume direct state rule of the population.[164] In 536 BC, Zichan had the legal statutes of his Zheng state inscribed on a bronze caldron or ding, and so made public, a first among the Eastern Zhou states.[165][166]

Au contraire, one modern view questions this notion that no state had published its laws before the late Spring and Autumn period. Creel raises doubts that laws were kept secret. He refers to the existence of earlier laws mentioned in ancient writings.[167][168] Creel mounts a direct challenge to several widely-quoted passages from the Zuo Zhuang that narrate: 1) how Zichan inscribed the Zheng laws on the bronze tripod ding in 536; and, 2) how Confucius criticized the similar publication of laws by a neighboring state in 513.[169]

Yet the story of Zichan being first to publish remains the modern consensus.[170][171][172][173][174][175] Zhao comments how the adverse political situation of Zheng "produced the legendary figure of Zichan, arguably the most influential reformer of his age. [Zichan's] most remarkable act was placing a caldron inscribed with Zheng's legal codes in a public place in 536". Judging by the fierce reaction generated, his action must have been considered "sensational at the time".[176] A law whose text was available to those subject to it, would work to foster their awareness of proper civic conduct. Published laws served the state, 1) as a way of guiding the people, and also 2) as a more effective tool of control, because it warns as well as legitimises punishment of violators. Zichan "had the complete support of the people of Cheng [Zheng], he enjoyed a position of full authority there throughout his life."[177][178][179][180]

Initial adverse reactions

For publishing the laws of Zheng, Zichan was criticized by some of his key contemporaries. It undermined the nobility, undercut their governing authority and their judicial role. Before, in making their legal judgments, the elite officials had applied to the facts their own confidential interpretation of what they viewed as the inherited social traditions, styled later 'rule by virtue'. The end result of this shrouded procedure would be very difficult to challenge.[181] By articulating and making public the legal statutes the people were better empowered to advance an opposing view of state law. Up until then ruling circles thought publishing the law would be detrimental, would open the door to public argument, bickering, and shameless maneuvering to avoid social tradition, its time-tested moral force.[182][183] The situation was multi-sided, as political roles were changing during a surge in growth of material culture; the social tradition itself was in flux. Opening up laws to be viewed by the common people would subsequently become the trend in pre-imperial Chinese statecraft.[184]

Deng Xi of Zheng (545-501 BC), for good or ill, acquired a reputation for provoking social conflict and civic instability. A child when Zichan published the laws, Deng Xi was a controversial official of Zheng with Mingjia philosophical views.[185] Despite being warned of the corrosive activities of the Mingjia, Zichan in 536 had an historic bronze ding cast inscribed with Zheng laws, probably penal laws. As Deng Xi came of age, he challenged the state and its ministers, including Zichan.[186][187][188][189] Some thought he studied trickery.[190] The state of Zheng in 501 put him to death. Ancient documents are divided as to who ordered his execution. Most probably it was not Zichan.[191][192][193]

A long 'letter' faulting Zichan for making the law public, was written by Shuxiang a minister of Jin and personal friend of Zichan. It marshaled strong traditional arguments against his publishing the penal laws of Zheng. Harshly accusing Zichan of grave error, it predicted future calamity. Responding Zichan claimed he was "untalented" and so unable to properly manage the laws with a view toward the future generations. To benefit people of Zheng alive today was his aim.[194][195][196][197][198][199] Issues at stake here were long debated, e.g., by philosophers of the Warring States era that soon followed, and which discussions continue today.[200][201]

Interstate relations

Zichan acted like a highly skilled realist in state-to-state politics. When the State of Jin tried to interfere in Zheng's internal affairs after the death of a Zheng minister, Zichan was aware of the danger. He argued that if Zheng allowed Jin to determine the minister's successor, Zheng lose its sovereignty. He eventually convinced Jin not to interfere in Zheng affairs.[202]

The Zuo Zhuan also mentions a summer meeting in 517 BC shortly after Zichan died. The Jin minister asked about ceremony and li (ritual propriety) of an official of Zheng, who then recounts a speech by "our former high officer" Zichan. The Zuo Zhuan quotes it at length. It is the book's "grandest exposition of ritual and its role in ordering human life in accordance with cosmic principles", according to the modern translators.[203][204][205] Feng comments on Zichan: "The idea expressed here... is that the practical value of ceremonials and music, punishments and penalties, lies in preventing the people from falling into disorder, and that these have originated from man's capacity for imitating Heaven and Earth."[206]

As a philosopher

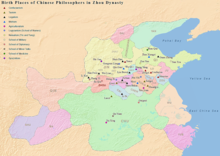

Zichan's political thinking is known from his words and actions as a minister of state. The kernels of his thought are thus found in the historical record, often in accounts of his exemplary conduct. His near contemporary Confucius mentioned him. In the next few centuries File:Birth Places of Chinese Philosophers.png his death, several Warring States philosophers wrote of him, on occasion creating suggestive contexts for his points of view. Zichan's public life earned him renown in his lifetime and a lasting reputation in ancient Chinese political thought.[207][208][209]

During the course of the Spring and Autumn period when Zichan was minister "the old order broke down". The people "were bewildered by the lack of standards for settling disputes and maintaining harmonious relationships." The old clan-based hereditary houses were losing their social status as the dominant authorities, but the rising new state regimes were still fragmented, divided and conflicted, and their emerging role as the controlling power lacked traditional sanction. The era's instability led to an increasingly militant search for innovative social structures.[210][211]

Zichan is "depicted in the [Zuo Zhuan] as one of the wisest men of his time, and also as a leading statesman in the small ancient state of [Zheng], which was under constant threat of extinction by its powerful neighbors". In his person evidently Zichan practiced the traditional li ceremonies and elite virtues of the fading Zhou dynasty (endorsed by Confucius). In his political craft, however, Han-era historians could see him as able to anticipate the later Legalist philosophy of the Warring States period, i.e., skillfull in the promulgation and enforcement of newly articulated laws. Such enforced obedience to state-wide standards would better secure the political control of events by the ministers.[212][213]

The Zuo Zhuan quotes at length from the words spoken by Zichan. His thoughts tended to separate the distant domains of Heaven and the near domain of the human world. He argued against superstition and acted to curb the authority of the Master of Divination. He counseled the people to follow their reason and experience. Heaven's way is distant and difficult to grasp; while the human way is near at hand.[214][215][216]

Confucius

Confucius (551-479 BC) was almost 30 when Zichan died. Only in the generation after Zichan did Confucius, an unsuccessful office seeker, establish the literate tradition of an independent, private teacher in China.[218]

As a near contemporary, like Zichan, Confucius was "born in [this] period of great political and social change", a centuries-long revolutionary "upheaval caused by forces beyond his control and already under way." Prof. Creel notes scholarly speculation about the original sources Confucius used in his teaching; he comments that the Zuo Zhuan quotes at length "several statesmen who, living shortly before Confucius... expressed ideas remarkably like his." They were "advanced in their thinking".[219]

The Han historian Sima Qian lists Zichan as one of the six teachers of Confucius.[220][221]

There were, of course, issues on which Zichan and Confucius did not agree. Confucius, then only 15, did not comment when Zichan caused the laws of Zheng to be published in 536.[222][223] Yet when later in 513 the neighboring city-state of Jin published its laws, Confucius clearly made known his strong opposition. Such actions undercut the traditional authority of the Zhou-dynasty kings and the city-state nobles who ruled in their name, which scheme of governance Confucius consistently idealized.[224][225]

Another area of disagreement touched on the human capacity to draw insights from observing society. Confucius taught about an ability to discern, from today's repetition of civic events, the distant future. By careful observation, change in the customary rites of a dynasty can indicate the course of its social history many generations hence.[226][227][228][229] Zichan, however, at a decisive moment of political conflict, was known to confess thet he was not talented enough to make such future predictions. So he tailored his decision only for the people of Zheng then living.[230]

According to the Lunyu, Confucius nonetheless spoke well of Zichan. In his personal conduct and attitudes, Zichan seemed to represent the traditional virtues Confucius advocated.

The Master said of Tsze-ch'an that he had four of the characteristics of a superior man: in his conduct of himself, he was humble; in serving his superiors, he was respectful; in nourishing the people, he was kind; in ordering the people, he was just."[231][232]

The Lüshi paired Confucius and Zichan (who in this translation is called 'Prince Chan'). Both are praised as talented state ministers who led their countries to significant achievements. Both became widely regarded as successful governors who directed others to accomplish the tasks of administration.[233]

Mencius

The Mengzi of Mencius[234] refers to Zichan. A perplexed disciple questions Mencius about the conduct of Shun, one of the legendary sage kings. Shun's hostile parents and family lied to him. Shun mistakenly believed them, but he did not reveal a corrupt nature thereby. Shun believed their lies because of his regard for his parents. A life of virtue is then discussed.

Mencius compared sage king Shun here to an episode about Zichan, when he had believed a dishonest servant. Zichan had given his groundskeeper a live fish to keep in a pond; instead he cooked and ate it. He later told Zichan the fish was alive and swimming in the pond. Zichan was happy that the fish "found his place". Hearing this from Zichan, the servant mocked his reputation for wisdom. But not Mencius, who concluded: "Thus a noble man may be taken in by what is right, but he cannot be misled by what is contrary to the way".[235][236][237]

Yet Menzi in another episode disapproved of Zichan's 'small kindness'.[238][239]

Bibliography

Ancient

- Zuo Zhuan (Commentary of Zuo), concerning the Spring and Autumn period,[240] translated as:

- The Ch'un Ts'ew[241] with the Tso Chuen (London: Henry Frowde 1872; reprint Taipei 1983),[242] tr. by James Legge;

- The Tso chuan. Selections from China's Oldest Narrative History (Columbia University 1989) tr. by Burton Watson;

- The Zuo Tradition (University of Washington 1989), 3 vols., tr. by Stephen Durrant, Li Wai-yee, David Schaberg;

- Zuo Tradition/Zuozhuan Reader. Selections (University of Washington 2020), by Durrant, Li, & Schaberg.

- Shijing, tr. as The Book of Odes by Karlgren,[243] as The Book of Songs by Waley,[244] as The Chinese Shi King by Jennings.[245][246]

- Shujing, tr. as The Most Venerable Book (Shang Shu) by Martin Palmer,[247] as Shu Ching. Book of History by Clae Waltham & Legge.[248]

- Lunyu of Kong Fuzi, translated as Analects of Confucius: Legge (1861, 1893),[249] Waley (1938), Ames (1998),[250] Brooks (1998).[251][252]

- 5: The Mengzi,[253][254] the Xunzi,[255][256][257] the Han Feizi,[258][259] (Warring States[260] philosophy); Sunzi (earlier military tract);[261][262] and, *Zichan (bamboo text, newly discovered).[263]

- Lüshi Chunqiu, transl. as The Annals of Lü Buwei (Stanford University 2001) by Knoblock & Riegel.[264]

- Shiji by Sima Qian, English translations:

- The Grand Scribe's Records (University of Indiana 1994-[2021], 12 vols. in process), William H. Nienhauser, Jr., editor;[265]

- Selections from Records of the Historian by Szuma Chien (Peking: Foreign Languages Press 1979), tr. by Yang and Yang.[266]

- Records of the Grand Historian of China. Translated from the Shih Chi of Ssu-Ma Ch'ien (Columbia University 1961, 2 vols.), by Watson.[267]

Modern

- Bodde, Derk and Clarence Morris, Law in Imperial China (University of Pennsylvania 1967).

- Chang, Kwang-Chih, Shang Civilization (Yale University 1980).

- Chang, K. C., Art, Myth, and Ritual. The path to political authority in ancient China (Harvard University 1983).

- Ch'ü T'ung-tsu, Law and Society in traditional China (Paris: Mouton & Co. 1961).

- Chu Tung-tsu,The History of Chinese Feudal Society ([1937], Routledge 2021).

- Collins, Randall, The Sociology of Philosophy. A global theory of intellectual change (Harvard University 1998).

- Creel, H. G., Confucius and the Chinese way (New York: John Day 1949, reprint: Harper, NY 1960).

- Creel, Herrlee G., The Origins of Statecraft in China, (University of Chicago 1970).

- Creel, Herrlee G., Shen Pu-hai. A political philosopher of the fourth century B.C. (University of Chicago 1974)

- Eberhard, Wolfram, Conquerors and Rulers. Social forces in medieval China (Leiden: E. J. Brill 1952).

- Falkenhausen, Lothar von, Chinese Society in the Age of Confucius (1000-250 BC). The archaeological evidence (UCLA 2006).

- Fung Yu-lan, Chung-kuo Che-hsüeh Shih (Shanghai 1931); A History of Chinese Philosophy, v.1 (Princeton Univ 1937, 2d 1952, 1983) tr. Bodde.

- Gernet, Jacques, Le Chine ancienne (1964), tr. Ancient China (University of California 1968) by Rudorff.

- Graham, A. C., Disputers of the Tao. Philosophical argument in ancient China (Chicago: Open Court 1989).

- Hsu Cho-yun, Ancient China in transition. An analysis of social mobility, 722-222 B.C. (Stanford University 1965)

- Hu Shih, The development of the logical method in ancient China, (Shanghai 1922; NY: Paragon 1963, reprint 2020)

- Jiang Tao, Origins of Moral-Political Philosophy in Early China (Oxford University 2021).

- Kaizuka Shigeki, Koshi (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten 1951); Confucius: His life & thought (New York: Macmillan 1956; Dover 2002), tr. Bownas.

- Lewis, Mark Edward, Sanctioned violence in early China (State University of New York 1990).

- Lewis, Mark Edward, Writing and Authority in early China, (State University of New York 1999).

- Lewis, Mark Edward, Honor and Shame in early China (Cambridge University 2021).

- Li Feng, Early China. A social and cultural history (Cambridge University 2013).

- Li Jun, Chinese civilization in the making, 1766-221 (New York: St. Martin's 1996).

- Lu Xing, Rhetoric in Ancient China (University of South Carolina 1998).

- Maspero, Henri, La Chine antique (Paris 1927, 1965), tr. China in Antiquity (University of Massachusetts 1978) by Kierman.

- Pines, Yuri, Foundations of Confucian thought: Intellectual life in the Chunqiu period, 722-453 (University of Hawaii 2002).

- Poo Mu-chou, In Search of Personal Welfare. A view of ancient Chinese religion (Albany: SUNY 1998).

- Rubin, Vitaly A., Ideologiia i kul'tura drevnego kitaia (Moscow 1970); Individual & State in Ancient China (NY: Columbia University 1976).

- Schwartz, Benjamin I., The World of Thought in Ancient China (Harvard University 1985).

- Su Li, The Constitution of Ancient China (Princeton University 2018).

- Sun Zhenbin, Language, Discourse, and Praxis in Ancient China (Springer 2015).

- Waley, Arthur, The Nine Songs (London: George Allen & Unwin 1955; reprint: City Lights, San Francisco 1973)

- Walker, Robert Louis, The Multi-state System of Ancient China. (Hamden: Shoestring 1953; Greenwood 1971).

- Zhang Jinfan, The tradition and modern transition of Chinese Law (Heidelberg: Springer 1997, 2d 2005, 3d 2008).

- Zhao Dingxin, The Confucian-Legalist State. A new theory of Chinese history (Oxford University 2015).

- Cheng K'o-tang, Tzu-ch'an p'ing chuan (Shanghai 1941).

- Jen Fangqiu, Zichan (Zhengzhou 1987).

Articles

- Creel, H. G., "Legal institutions & procedures during the Chou dynasty", in Cohen, Edwards, Chen (ed), Essays on China's Legal Tradition (1980).

- Dull, Jack L., "The deep roots of resistance to Law Codes and Lawyers in China", in Turner, et el. (eds.), The limits of the rule of law in China (2000).

- Eichler, E. R., "The Life of Tsze-ch'an," in China Review (1886), vol. XV: pp. 12–23 & 65-78.[270]

- Fraser, Chris, "School of Names": Deng Xi (2015), in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Archive.

- Lewis, Mark Edward, "The City-State in Spring and Autumn China", in Hansen (ed.), A Comparative study of thirty City-State cultures (Copenhagen 2000).

- Martin, François, "Le cas de Zichan", in Gernet & Kalinowski (eds.), En Suivant la Voie Royale (1997).[271]

- Puett, Michael, "Ghosts, Gods, & Coming Apocalypse," in Scheidel (ed.), State Power in Ancient China & Rome (Oxford University 2015).

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G., "Ji and Jiang: The role of exogamic clans in the organization of Zhou polity", in Early China (2000), v.25: pp. 1-27.

- Rubin, V. A., "Tzu-Ch'an and the city-state of ancient China" in T'oung Pao, v.52: pp. 8-34 (1965).

- Theobald, Ulrich, "Zichan" (2010), at ChinaKnowledge website, accessed 2022-07-27.

- Theobald, Ulrich, "Regional State of Zheng" (2000), at ChinaKnowledge, accessed 2023-06-16.

- Turner, Karen, "Sage kings and laws in the Chinese and Greek traditions," in Ropp (ed.), Heritage of China (University of California 1990).

- Wang Hui, "The mixed Han-Tang-Song structure and its moral ideal" in Su Li, The Constitution of ancient China (2018).

- Yang, C. K., "Introduction" (1964) to Weber, Religion of China ([1916]; NY: Macmillan 1951, 1964).

- Cook & Major, editors, Defining Chu. Image and reality in ancient China (University of Hawai'i 1999).[272][273][274][275][276][277]

- Goldin, Paul R., editor, Routledge Handbook of early Chinese history (2020).[278][279][280][281][282][283]

- Loewe & Shaughnessy, editors, The Cambridge History of Ancient China (1999).[284][285][286][287][288]

- Loewe, Michael, editor, Early Chinese Texts. A bibliographical guide (SSEC & IEAS/U.Calif. 1993).