Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it also includes indirect methods aimed at forced migration by coercing the victim group to flee and preventing its return, such as murder, rape, and property destruction.[1][2][3][4][5] Both the definition and charge of ethnic cleansing is often disputed, with some researchers including and others excluding coercive assimilation or mass killings as a means of depopulating an area of a particular group.[6][7][8]

Although scholars do not agree on which events constitute ethnic cleansing,[7] many instances have occurred throughout history; the term was first used during the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s by the perpetrators as a euphemism for genocidal practices. Since then, the term has gained widespread acceptance due to journalism.[9] Although research originally focused on deep-rooted animosities as an explanation for ethnic cleansing events, more recent studies depict ethnic cleansing as "a natural extension of the homogenizing tendencies of nation states" or emphasize security concerns and the effects of democratization, portraying ethnic tensions as a contributing factor. Research has also focused on the role of war as a causative or potentiating factor in ethnic cleansing. However, states in a similar strategic situation can have widely varying policies towards minority ethnic groups perceived as a security threat.[10]

Ethnic cleansing has no legal definition under international criminal law, but the methods by which it is carried out are considered crimes against humanity and may also fall under the Genocide Convention.[1][11][12]

Etymology

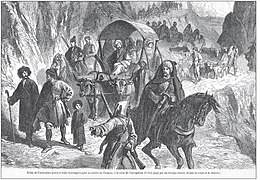

An antecedent to the term is the Greek word andrapodismos (ἀνδραποδισμός; lit. "enslavement"), which was used in ancient texts. e.g., to describe atrocities that accompanied Alexander the Great's conquest of Thebes in 335 BCE.[16] Circassian genocide, also known as "Tsitsekun", is often regarded by various historians as the first large-scale ethnic cleansing campaign launched by a state during the 19th century industrial era.[17][18] Imperial Russian general Nikolay Yevdakimov, who supervised the operations of Circassian genocide during 1860s, dehumanised Muslim Circassians as "a pestilence" to be expelled from their native lands. Russian objective was the annexation of land; and the Russian military operations that forcibly deported Circassians were designated by Yevdakimov as “ochishchenie” (cleansing).[13]

In the early 1900s, regional variants of the term could be found among the Czechs (očista), the Poles (czystki etniczne), the French (épuration) and the Germans (Säuberung).[19][page needed] A 1913 Carnegie Endowment report condemning the actions of all participants in the Balkan Wars contained various new terms to describe brutalities committed toward ethnic groups.[20]

During World War II, the euphemism čišćenje terena ("cleansing the terrain") was used by the Croatian Ustaše to describe military actions in which non-Croats were purposely killed or otherwise uprooted from their homes.[21] Viktor Gutić, a senior Ustaše leader, was one of the first Croatian nationalists on record to use the term as a euphemism for committing atrocities against Serbs.[22] The term was later used in the internal memorandums of Serbian Chetniks in reference to a number of retaliatory massacres they committed against Bosniaks and Croats between 1941 and 1945.[23] The Russian phrase очистка границ (ochistka granits; lit. "cleansing of borders") was used in Soviet documents of the early 1930s to refer to the forced resettlement of Polish people from the 22-kilometre (14 mi) border zone in the Byelorussian and Ukrainian SSRs.[citation needed] This process of the population transfer in the Soviet Union was repeated on an even larger scale in 1939–1941, involving many other groups suspected of disloyalty.[24] During the Holocaust, Nazi Germany pursued a policy of ensuring that Europe was "cleaned of Jews" (judenrein).[25] The Nazi Generalplan Ost called for the genocide and ethnic cleansing of most Slavic people in central and eastern Europe for the purpose of providing more living space for the Germans.[26]

In its complete form, the term appeared for the first time in the Romanian language (purificare etnică) in an address by Vice Prime Minister Mihai Antonescu to cabinet members in July 1941. After the beginning of the invasion by the Soviet Union,[clarification needed] he concluded: "I do not know when the Romanians will have such chance for ethnic cleansing."[27] In the 1980s, the Soviets used the term "etnicheskoye chishcheniye" which literally translates to "ethnic cleansing" to describe Azerbaijani efforts to drive Armenians away from Nagorno-Karabakh.[28][29][30] At around the same time, the Yugoslav media used it to describe what they alleged was an Albanian nationalist plot to force all Serbs to leave Kosovo. It was widely popularized by the Western media during the Bosnian War (1992–1995).

In 1992, the German equivalent of ethnic cleansing (German: ethnische Säuberung, pronounced [ˈʔɛtnɪʃə ˈzɔɪ̯bəʁʊŋ] ⓘ) was named German Un-word of the Year by the Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache due to its euphemistic, inappropriate nature.[31]

Definitions

The Final Report of the Commission of Experts established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 780 defined ethnic cleansing as:

a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic or religious group from certain geographic areas", [noting that in the former Yugoslavia] " 'ethnic cleansing' has been carried out by means of murder, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, extra-judicial executions, rape and sexual assaults, confinement of civilian population in ghetto areas, forcible removal, displacement and deportation of civilian population, deliberate military attacks or threats of attacks on civilians and civilian areas, and wanton destruction of property. Those practices constitute crimes against humanity and can be assimilated to specific war crimes. Furthermore, such acts could also fall within the meaning of the Genocide Convention.[32][33]

The official United Nations definition of ethnic cleansing is "rendering an area ethnically homogeneous by using force or intimidation to remove from a given area persons of another ethnic or religious group."[34] As a category, ethnic cleansing encompasses a continuum or spectrum of policies. In the words of Andrew Bell-Fialkoff, "ethnic cleansing ... defies easy definition. At one end it is virtually indistinguishable from forced emigration and population exchange while at the other it merges with deportation and genocide. At the most general level, however, ethnic cleansing can be understood as the expulsion of a population from a given territory."[35]

Terry Martin has defined ethnic cleansing as "the forcible removal of an ethnically defined population from a given territory" and as "occupying the central part of a continuum between genocide on one end and nonviolent pressured ethnic emigration on the other end."[24]

Gregory Stanton, the founder of Genocide Watch, has criticised the rise of the term and its use for events that he feels should be called "genocide": because "ethnic cleansing" has no legal definition, its media use can detract attention from events that should be prosecuted as genocide.[36][37]

As a crime under international law

There is no international treaty that specifies a specific crime of ethnic cleansing;[38] however, ethnic cleansing in the broad sense—the forcible deportation of a population—is defined as a crime against humanity under the statutes of both the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY).[39] The gross human rights violations integral to stricter definitions of ethnic cleansing are treated as separate crimes falling under public international law of crimes against humanity and in certain circumstances genocide.[40] There are also situations, such as the expulsion of Germans after World War II, where ethnic cleansing has taken place without legal redress (see Preussische Treuhand v. Poland). Timothy v. Waters argues that similar ethnic cleansing could go unpunished in the future.[41]

Mutual ethnic cleansing

Mutual ethnic cleansing occurs when two groups commit ethnic cleansing against minority members of the other group within their own territories. For instance in the 1920s, Turkey expelled its Greek minority and Greece expelled its Turkish minority following the Greco-Turkish War.[42] Other examples where mutual ethnic cleansing occurred include the First Nagorno-Karabakh War[43] and the population transfers by the Soviets of Germans, Poles and Ukrainians after World War II.[44]

Causes

According to Michael Mann, in The Dark Side of Democracy (2004), murderous ethnic cleansing is strongly related to the creation of democracies. He argues that murderous ethnic cleansing is due to the rise of nationalism, which associates citizenship with a specific ethnic group. Democracy, therefore, is tied to ethnic and national forms of exclusion. Nevertheless, it is not democratic states that are more prone to commit ethnic cleansing, because minorities tend to have constitutional guarantees. Neither are stable authoritarian regimes (except the nazi and communist regimes) which are likely perpetrators of murderous ethnic cleansing, but those regimes that are in process of democratization. Ethnic hostility appears where ethnicity overshadows social classes as the primordial system of social stratification. Usually, in deeply divided societies, categories such as class and ethnicity are deeply intertwined, and when an ethnic group is seen as oppressor or exploitative of the other, serious ethnic conflict can develop. Michael Mann holds that when two ethnic groups claim sovereignty over the same territory and can feel threatened, their differences can lead to severe grievances and danger of ethnic cleansing. The perpetration of murderous ethnic cleansing tends to occur in unstable geopolitical environments and in contexts of war. As ethnic cleansing requires high levels of organisation and is usually directed by states or other authoritative powers, perpetrators are usually state powers or institutions with some coherence and capacity, not failed states as it is generally perceived. The perpetrator powers tend to get support by core constituencies that favour combinations of nationalism, statism and violence.[45]

Ethnic cleansing was prevalent during the Age of Nationalism in Europe (19th and 20th centuries).[46][47] Multi-ethnic European engaged in ethnic cleansing against minorities in order to pre-empt their secession and the loss of territory.[46] Ethnic cleansing was particularly prevalent during periods of interstate war.[46]

Genocide

Ethnic cleansing has been described as part of a continuum of violence whose most extreme form is genocide. Ethnic cleansing is similar to forced deportation or population transfer. While ethnic cleansing and genocide may share the same goal and methods (e.g., forced displacement), ethnic cleansing is intended to displace a persecuted population from a given territory, while genocide is intended to destroy a group.[48][49]

Some academics consider genocide to be a subset of "murderous ethnic cleansing".[50] As Norman Naimark writes, these concepts are different but related, for "literally and figuratively, ethnic cleansing bleeds into genocide, as mass murder is committed in order to rid the land of a people."[51] William Schabas states "ethnic cleansing is also a warning sign of genocide to come. Genocide is the last resort of the frustrated ethnic cleanser."[48] Multiple genocide scholars have criticized distinguishing between ethnic cleansing and genocide, arguing that because both ultimately result in the destruction of a group, the use of the term "ethnic cleansing" is a form of genocide denial.[a][52][36][37]

As a military, political, and economic tactic

The foibe massacres, or simply "the foibe", refers to mass killings both during and after World War II, mainly committed by Yugoslav Partisans and OZNA in the then-Italian territories[b] of Julian March (Karst Region and Istria), Kvarner and Dalmatia also against the local ethnic Italian population (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians).[53][54] The type of attack was state terrorism[53] and ethnic cleansing against Italians.[53][54][55][56][57] The foibe massacres were followed by the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus, which was the post-World War II exodus and departure of between 230,000 and 350,000 local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) towards Italy, and in smaller numbers, towards the Americas, Australia and South Africa.[58][59] From 1947, after the war, they were subject by Yugoslav authorities to less violent forms of intimidation, such as nationalization, expropriation, and discriminatory taxation,[60] which gave them little option other than emigration.[61][62][63] In 1953, there were 36,000 declared Italians in Yugoslavia, just about 16% of the original Italian population before World War II.[64] According to the census organized in Croatia in 2001 and that organized in Slovenia in 2002, the Italians who remained in the former Yugoslavia amounted to 21,894 people (2,258 in Slovenia and 19,636 in Croatia).[65][66]

Israeli herders have engaged in a systemic displacement of Palestinian herders in Area C of the West Bank as a form of nationalist and economic warfare.[67][68]

When enforced as part of a political settlement, as happened with the expulsion of Germans after World War II through the forced resettlement of ethnic Germans to Germany in its reduced borders after 1945, the forced population movements, constituting a type of ethnic cleansing, may contribute to long-term stability of a post-conflict nation.[71][page needed] Some justifications may be made as to why the targeted group will be moved in the conflict resolution stages, as in the case of the ethnic Germans, some individuals of the large German population in Czechoslovakia and prewar Poland had encouraged Nazi jingoism before World War II, but this was forcibly resolved.[71][page needed]

According to historian Norman Naimark, during an ethnic cleansing process, there may be destruction of physical symbols of the victims including temples, books, monuments, graveyards, and street names: "Ethnic cleansing involves not only the forced deportation of entire nations but the eradication of the memory of their presence."[72] In many cases, the side perpetrating the alleged ethnic cleansing and its allies have fiercely disputed the charge.[clarification needed]

Instances

See also

- Cultural genocide

- Discrimination based on skin color

- Ethnic conflict

- Ethnic penalty

- Ethnic violence

- Ethnocentrism

- Ethnocide

- Forced displacement

- Gerrymandering

- Identity cleansing

- Identity politics

- Nativism (politics)

- Political cleansing of population

- Population cleansing

- Racial segregation

- Racism

- Redlining

- Religious cleansing

- Religious discrimination

- Religious intolerance

- Religious segregation

- Religious violence

- Sectarian violence

- Social cleansing

- Social distancing

- Sundown town

- Supremacism

- Xenophobia

Explanatory notes

Notes

References

Further reading

External links