There are 95 moons of Jupiter with confirmed orbits as of 5 February 2024[update].[1][note 1] This number does not include a number of meter-sized moonlets thought to be shed from the inner moons, nor hundreds of possible kilometer-sized outer irregular moons that were only briefly captured by telescopes.[4] All together, Jupiter's moons form a satellite system called the Jovian system. The most massive of the moons are the four Galilean moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, which were independently discovered in 1610 by Galileo Galilei and Simon Marius and were the first objects found to orbit a body that was neither Earth nor the Sun. Much more recently, beginning in 1892, dozens of far smaller Jovian moons have been detected and have received the names of lovers (or other sexual partners) or daughters of the Roman god Jupiter or his Greek equivalent Zeus. The Galilean moons are by far the largest and most massive objects to orbit Jupiter, with the remaining 91 known moons and the rings together composing just 0.003% of the total orbiting mass.

Of Jupiter's moons, eight are regular satellites with prograde and nearly circular orbits that are not greatly inclined with respect to Jupiter's equatorial plane. The Galilean satellites are nearly spherical in shape due to their planetary mass, and are just massive enough that they would be considered major planets if they were in direct orbit around the Sun. The other four regular satellites, known as the inner moons, are much smaller and closer to Jupiter; these serve as sources of the dust that makes up Jupiter's rings. The remainder of Jupiter's moons are outer irregular satellites whose prograde and retrograde orbits are much farther from Jupiter and have high inclinations and eccentricities. The largest of these moons were likely asteroids that were captured from solar orbits by Jupiter before impacts with other small bodies shattered them into many kilometer-sized fragments, forming collisional families of moons sharing similar orbits. Jupiter is expected to have about 100 irregular moons larger than 1 km (0.6 mi) in diameter, plus around 500 more smaller retrograde moons down to diameters of 0.8 km (0.5 mi).[5] Of the 87 known irregular moons of Jupiter, 38 of them have not yet been officially named.

Characteristics

The physical and orbital characteristics of the moons vary widely. The four Galileans are all over 3,100 kilometres (1,900 mi) in diameter; the largest Galilean, Ganymede, is the ninth largest object in the Solar System, after the Sun and seven of the planets, Ganymede being larger than Mercury. All other Jovian moons are less than 250 kilometres (160 mi) in diameter, with most barely exceeding 5 kilometres (3.1 mi).[note 2] Their orbital shapes range from nearly perfectly circular to highly eccentric and inclined, and many revolve in the direction opposite to Jupiter's rotation (retrograde motion). Orbital periods range from seven hours (taking less time than Jupiter does to rotate around its axis), to almost three Earth years.

Origin and evolution

Jupiter's regular satellites are believed to have formed from a circumplanetary disk, a ring of accreting gas and solid debris analogous to a protoplanetary disk.[6][7] They may be the remnants of a score of Galilean-mass satellites that formed early in Jupiter's history.[6][8]

Simulations suggest that, while the disk had a relatively high mass at any given moment, over time a substantial fraction (several tens of a percent) of the mass of Jupiter captured from the solar nebula was passed through it. However, only 2% of the proto-disk mass of Jupiter is required to explain the existing satellites.[6] Thus, several generations of Galilean-mass satellites may have been in Jupiter's early history. Each generation of moons might have spiraled into Jupiter, because of drag from the disk, with new moons then forming from the new debris captured from the solar nebula.[6] By the time the present (possibly fifth) generation formed, the disk had thinned so that it no longer greatly interfered with the moons' orbits.[8] The current Galilean moons were still affected, falling into and being partially protected by an orbital resonance with each other, which still exists for Io, Europa, and Ganymede: they are in a 1:2:4 resonance. Ganymede's larger mass means that it would have migrated inward at a faster rate than Europa or Io.[6] Tidal dissipation in the Jovian system is still ongoing and Callisto will likely be captured into the resonance in about 1.5 billion years, creating a 1:2:4:8 chain.[9]

The outer, irregular moons are thought to have originated from captured asteroids, whereas the protolunar disk was still massive enough to absorb much of their momentum and thus capture them into orbit. Many are believed to have been broken up by mechanical stresses during capture, or afterward by collisions with other small bodies, producing the moons we see today.[10]

History and discovery

Visual observations

Chinese historian Xi Zezong claimed that the earliest record of a Jovian moon (Ganymede or Callisto) was a note by Chinese astronomer Gan De of an observation around 364 BC regarding a "reddish star".[11] However, the first certain observations of Jupiter's satellites were those of Galileo Galilei in 1609.[12] By January 1610, he had sighted the four massive Galilean moons with his 20× magnification telescope, and he published his results in March 1610.[13]

Simon Marius had independently discovered the moons one day after Galileo, although he did not publish his book on the subject until 1614. Even so, the names Marius assigned are used today: Ganymede, Callisto, Io, and Europa.[14] No additional satellites were discovered until E. E. Barnard observed Amalthea in 1892.[15]

Photographic and spacecraft observations

With the aid of telescopic photography with photographic plates, further discoveries followed quickly over the course of the 20th century. Himalia was discovered in 1904,[16] Elara in 1905,[17] Pasiphae in 1908,[18] Sinope in 1914,[19] Lysithea and Carme in 1938,[20] Ananke in 1951,[21] and Leda in 1974.[22]

By the time that the Voyager space probes reached Jupiter, around 1979, thirteen moons had been discovered, not including Themisto, which had been observed in 1975,[23] but was lost until 2000 due to insufficient initial observation data. The Voyager spacecraft discovered an additional three inner moons in 1979: Metis, Adrastea, and Thebe.[24]

Digital telescopic observations

No additional moons were discovered until two decades later, with the fortuitous discovery of Callirrhoe by the Spacewatch survey in October 1999.[25] During the 1990s, photographic plates phased out as digital charge-coupled device (CCD) cameras began emerging in telescopes on Earth, allowing for wide-field surveys of the sky at unprecedented sensitivities and ushering in a wave of new moon discoveries.[26] Scott Sheppard, then a graduate student of David Jewitt, demonstrated this extended capability of CCD cameras in a survey conducted with the Mauna Kea Observatory's 2.2-meter (88 in) UH88 telescope in November 2000, discovering eleven new irregular moons of Jupiter including the previously lost Themisto with the aid of automated computer algorithms.[27]

From 2001 onward, Sheppard and Jewitt alongside other collaborators continued surveying for Jovian irregular moons with the 3.6-meter (12 ft) Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT), discovering an additional eleven in December 2001, one in October 2002, and nineteen in February 2003.[27][1] At the same time, another independent team led by Brett J. Gladman also used the CFHT in 2003 to search for Jovian irregular moons, discovering four and co-discovering two with Sheppard.[1][28][29] From the start to end of these CCD-based surveys in 2000–2004, Jupiter's known moon count had grown from 17 to 63.[25][28] All of these moons discovered after 2000 are faint and tiny, with apparent magnitudes between 22–23 and diameters less than 10 km (6.2 mi).[27] As a result, many could not be reliably tracked and ended up becoming lost.[30]

Beginning in 2009, a team of astronomers, namely Mike Alexandersen, Marina Brozović, Brett Gladman, Robert Jacobson, and Christian Veillet, began a campaign to recover Jupiter's lost irregular moons using the CFHT and Palomar Observatory's 5.1-meter (17 ft) Hale Telescope.[31][30] They discovered two previously unknown Jovian irregular moons during recovery efforts in September 2010, prompting further follow-up observations to confirm these by 2011.[31][32] One of these moons, S/2010 J 2 (now Jupiter LII), has an apparent magnitude of 24 and a diameter of only 1–2 km (0.62–1.2 mi), making it one of the faintest and smallest confirmed moons of Jupiter even as of 2023[update].[33][4] Meanwhile, in September 2011, Scott Sheppard, now a faculty member of the Carnegie Institution for Science,[4] discovered two more irregular moons using the institution's 6.5-meter (21 ft) Magellan Telescopes at Las Campanas Observatory, raising Jupiter's known moon count to 67.[34] Although Sheppard's two moons were followed up and confirmed by 2012, both became lost due to insufficient observational coverage.[30][35]

In 2016, while surveying for distant trans-Neptunian objects with the Magellan Telescopes, Sheppard serendipitously observed a region of the sky located near Jupiter, enticing him to search for Jovian irregular moons as a detour. In collaboration with Chadwick Trujillo and David Tholen, Sheppard continued surveying around Jupiter from 2016 to 2018 using the Cerro Tololo Observatory's 4.0-meter (13 ft) Víctor M. Blanco Telescope and Mauna Kea Observatory's 8.2-meter (27 ft) Subaru Telescope.[36][37] In the process, Sheppard's team recovered several lost moons of Jupiter from 2003 to 2011 and reported two new Jovian irregular moons in June 2017.[38] Then in July 2018, Sheppard's team announced ten more irregular moons confirmed from 2016 to 2018 observations, bringing Jupiter's known moon count to 79. Among these was Valetudo, which has an unusually distant prograde orbit that crosses paths with the retrograde irregular moons.[36][37] Several more unidentified Jovian irregular satellites were detected in Sheppard's 2016–2018 search, but were too faint for follow-up confirmation.[37][39]: 10

From November 2021 to January 2023, Sheppard discovered twelve more irregular moons of Jupiter and confirmed them in archival survey imagery from 2003 to 2018, bringing the total count to 92.[40][2][3] Among these was S/2018 J 4, a highly-inclined prograde moon that is now known to be in same orbital grouping as the moon Carpo, which was previously thought to be solitary.[3] On 22 February 2023, Sheppard announced three more moons discovered in a 2022 survey, now bringing Jupiter's total known moon count to 95.[2] In a February 2023 interview with NPR, Sheppard noted that he and his team are currently tracking even more moons of Jupiter, which should place Jupiter's moon count over 100 once confirmed over the next two years.[41]

Many more irregular moons of Jupiter will inevitably be discovered in the future, especially after the beginning of deep sky surveys by the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory and Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope in the mid-2020s.[42][43] The Rubin Observatory's 8.4-meter (28 ft) aperture telescope and 3.5 square-degree field of view will probe Jupiter's irregular moons down to diameters of 1 km (0.6 mi)[10]: 265 at apparent magnitudes of 24.5, with the potential of increasing the known population by up to tenfold.[42]: 292 Likewise, the Roman Space Telescope's 2.4-meter (7.9 ft) aperture and 0.28 square-degree field of view will probe Jupiter's irregular moons down to diameters of 0.3 km (0.2 mi) at magnitude 27.7, with the potential of discovering approximately 1,000 Jovian moons above this size.[43]: 24 Discovering these many irregular satellites will help reveal their population's size distribution and collisional histories, which will place further constraints to how the Solar System formed.[43]: 24–25

Discovery of outer planet moons

Naming

The Galilean moons of Jupiter (Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto) were named by Simon Marius soon after their discovery in 1610.[44] However, these names fell out of favor until the 20th century. The astronomical literature instead simply referred to "Jupiter I", "Jupiter II", etc., or "the first satellite of Jupiter", "Jupiter's second satellite", and so on.[44] The names Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto became popular in the mid-20th century,[45] whereas the rest of the moons remained unnamed and were usually numbered in Roman numerals V (5) to XII (12).[46][47] Jupiter V was discovered in 1892 and given the name Amalthea by a popular though unofficial convention, a name first used by French astronomer Camille Flammarion.[48][49]

The other moons were simply labeled by their Roman numeral (e.g. Jupiter IX) in the majority of astronomical literature until the 1970s.[50] Several different suggestions were made for names of Jupiter's outer satellites, but none were universally accepted until 1975 when the International Astronomical Union's (IAU) Task Group for Outer Solar System Nomenclature granted names to satellites V–XIII,[51] and provided for a formal naming process for future satellites still to be discovered.[51] The practice was to name newly discovered moons of Jupiter after lovers and favorites of the god Jupiter (Zeus) and, since 2004, also after their descendants.[48] All of Jupiter's satellites from XXXIV (Euporie) onward are named after descendants of Jupiter or Zeus,[48] except LIII (Dia), named after a lover of Jupiter. Names ending with "a" or "o" are used for prograde irregular satellites (the latter for highly inclined satellites), and names ending with "e" are used for retrograde irregulars.[26] With the discovery of smaller, kilometre-sized moons around Jupiter, the IAU has established an additional convention to limit the naming of small moons with absolute magnitudes greater than 18 or diameters smaller than 1 km (0.6 mi).[52] Some of the most recently confirmed moons have not received names.[4]

Some asteroids share the same names as moons of Jupiter: 9 Metis, 38 Leda, 52 Europa, 85 Io, 113 Amalthea, 239 Adrastea. Two more asteroids previously shared the names of Jovian moons until spelling differences were made permanent by the IAU: Ganymede and asteroid 1036 Ganymed; and Callisto and asteroid 204 Kallisto.

Groups

Regular satellites

These have prograde and nearly circular orbits of low inclination and are split into two groups:

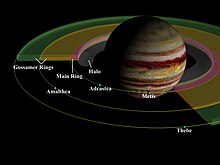

- Inner satellites or Amalthea group: Metis, Adrastea, Amalthea, and Thebe. These orbit very close to Jupiter; the innermost two orbit in less than a Jovian day. The latter two are respectively the fifth and seventh largest moons in the Jovian system. Observations suggest that at least the largest member, Amalthea, did not form on its present orbit, but farther from the planet, or that it is a captured Solar System body.[53] These moons, along with a number of seen and as-yet-unseen inner moonlets (see Amalthea moonlets), replenish and maintain Jupiter's faint ring system. Metis and Adrastea help to maintain Jupiter's main ring, whereas Amalthea and Thebe each maintain their own faint outer rings.[54][55]

- Main group or Galilean moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. They are some of the largest objects in the Solar System outside the Sun and the eight planets in terms of mass, larger than any known dwarf planet. Ganymede exceeds (and Callisto nearly equals) even the planet Mercury in diameter, though they are less massive. They are respectively the fourth-, sixth-, first-, and third-largest natural satellites in the Solar System, containing approximately 99.997% of the total mass in orbit around Jupiter, while Jupiter is almost 5,000 times more massive than the Galilean moons.[note 3] The inner moons are in a 1:2:4 orbital resonance. Models suggest that they formed by slow accretion in the low-density Jovian subnebula—a disc of the gas and dust that existed around Jupiter after its formation—which lasted up to 10 million years in the case of Callisto.[56] Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto are suspected of having subsurface water oceans,[57][58] and Io may have a subsurface magma ocean.[59]

Irregular satellites

The irregular satellites are substantially smaller objects with more distant and eccentric orbits. They form families with shared similarities in orbit (semi-major axis, inclination, eccentricity) and composition; it is believed that these are at least partially collisional families that were created when larger (but still small) parent bodies were shattered by impacts from asteroids captured by Jupiter's gravitational field. These families bear the names of their largest members. The identification of satellite families is tentative, but the following are typically listed:[4][60][61]

- Prograde satellites:

- Themisto is the innermost irregular moon and is not part of a known family.[4][60]

- The Himalia group is confined within semi-major axes between 11–12 million km (6.8–7.5 million mi), inclinations between 27–29°, and eccentricities between 0.12 and 0.21.[62] It has been suggested that the group could be a remnant of the break-up of an asteroid from the asteroid belt.[60]

- The Carpo group includes two known moons on very high orbital inclinations of 50° and semi-major axes between 16–17 million km (9.9–10.6 million mi).[4] Due to their exceptionally high inclinations, the moons of the Carpo group are subject to gravitational perturbations that induce the Lidov–Kozai resonance in their orbits, which cause their eccentricities and inclinations to periodically oscillate in correspondence with each other.[35] The Lidov–Kozai resonance can significantly alter the orbits of these moons: for example, the eccentricity and inclination of the group's namesake Carpo can fluctuate between 0.19–0.69 and 44–59°, respectively.[35]

- Valetudo is the outermost prograde moon and is not part of a known family. Its prograde orbit crosses paths with several moons that have retrograde orbits and may in the future collide with them.[37]

- Retrograde satellites:

- The Carme group is tightly confined within semi-major axes between 22–24 million km (14–15 million mi), inclinations between 164–166°, and eccentricities between 0.25 and 0.28.[62] It is very homogeneous in color (light red) and is believed to have originated as collisional fragments from a D-type asteroid progenitor, possibly a Jupiter trojan.[27]

- The Ananke group has a relatively wider spread than the previous groups, with semi-major axes between 19–22 million km (12–14 million mi), inclinations between 144–156°, and eccentricities between 0.09 and 0.25.[62] Most of the members appear gray, and are believed to have formed from the breakup of a captured asteroid.[27]

- The Pasiphae group is quite dispersed, with semi-major axes spread over 22–25 million km (14–16 million mi), inclinations between 141° and 157°, and higher eccentricities between 0.23 and 0.44.[62] The colors also vary significantly, from red to grey, which might be the result of multiple collisions. Sinope, sometimes included in the Pasiphae group,[27] is red and, given the difference in inclination, it could have been captured independently;[60] Pasiphae and Sinope are also trapped in secular resonances with Jupiter.[63]

Based on their survey discoveries in 2000–2003, Sheppard and Jewitt predicted that Jupiter should have approximately 100 irregular satellites larger than 1 km (0.6 mi) in diameter, or brighter than magnitude 24.[27]: 262 Survey observations by Alexandersen et al. in 2010–2011 agreed with this prediction, estimating that approximately 40 Jovian irregular satellites of this size remained undiscovered in 2012.[31]: 4

In September 2020, researchers from the University of British Columbia identified 45 candidate irregular moons from an analysis of archival images taken in 2010 by the CFHT.[64] These candidates were mainly small and faint, down to magnitude of 25.7 or above 0.8 km (0.5 mi) in diameter. From the number of candidate moons detected within a sky area of one square degree, the team extrapolated that the population of retrograde Jovian moons brighter than magnitude 25.7 is around 600+600

−300 within a factor of 2.[5]: 6 Although the team considers their characterized candidates to be likely moons of Jupiter, they all remain unconfirmed due to insufficient observation data for determining reliable orbits.[64] The true population of Jovian irregular moons is likely complete down to magnitude 23.2 at diameters over 3 km (1.9 mi) as of 2020[update].[5]: 6 [31]: 4

List

The moons of Jupiter are listed below by orbital period. Moons massive enough for their surfaces to have collapsed into a spheroid are highlighted in bold. These are the four Galilean moons, which are comparable in size to the Moon. The other moons are much smaller. The Galilean moon with the smallest amount of mass is greater than 7,000 times more massive than the most massive of the other moons. The irregular captured moons are shaded light gray and orange when prograde and yellow, red, and dark gray when retrograde.

The orbits and mean distances of the irregular moons are highly variable over short timescales due to frequent planetary and solar perturbations,[35] so proper orbital elements which are averaged over a period of time are preferably used. The proper orbital elements of the irregular moons listed here are averaged over a 400-year numerical integration by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory: for the above reasons, they may strongly differ from osculating orbital elements provided by other sources.[62] Otherwise, recently-discovered irregular moons without published proper elements are temporarily listed here with inaccurate osculating orbital elements that are italicized to distinguish them from other irregular moons with proper orbital elements. Some of the irregular moons' proper orbital periods in this list may not scale accordingly with their proper semi-major axes due to the aforementioned perturbations. The irregular moons' proper orbital elements are all based on the reference epoch of 1 January 2000.[62]

Some irregular moons have only been observed briefly for a year or two, but their orbits are known accurately enough that they will not be lost to positional uncertainties.[35][4]

| Key | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner moons | ♠ Galilean moons | † Themisto | ♣ Himalia group | § Carpo group | ± Valetudo | ♦ Ananke group | ♥ Carme group | ‡ Pasiphae group |

| Label [note 4] | Name | Pronunciation | Image | Abs. magn.[65] | Diameter (km)[4][note 5] | Mass (×1016 kg)[66][note 6] | Semi-major axis (km)[62] | Orbital period (d) [62][note 7] | Inclination (°)[62] | Eccentricity [4] | Discovery year[1] | Year announced | Discoverer[48][1] | Group [note 8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XVI | Metis | /ˈmiːtəs/ |  | 10.5 | 43 (60 × 40 × 34) | ≈ 3.6 | 128000 | +0.2948 (+7h 04m 29s) | 0.060 | 0.0002 | 1979 | 1980 | Synnott (Voyager 1) | Inner |

| XV | Adrastea | /ædrəˈstiːə/ |  | 12.0 | 16.4 (20 × 16 × 14) | ≈ 0.20 | 129000 | +0.2983 (+7h 09m 30s) | 0.030 | 0.0015 | 1979 | 1979 | Jewitt (Voyager 2) | Inner |

| V | Amalthea | /æməlˈθiːə/[67] |  | 7.1 | 167 (250 × 146 × 128) | 208 | 181400 | +0.4999 (+11h 59m 53s) | 0.374 | 0.0032 | 1892 | 1892 | Barnard | Inner |

| XIV | Thebe | /ˈθiːbiː/ |  | 9.0 | 98.6 (116 × 98 × 84) | ≈ 43 | 221900 | +0.6761 (+16h 13m 35s) | 1.076 | 0.0175 | 1979 | 1980 | Synnott (Voyager 1) | Inner |

| I | Io♠ | /ˈaɪoʊ/ |  | -1.7 | 3643.2 (3660 × 3637 × 3631) | 8931900 | 421800 | +1.7627 (+1d 18h 18m 20s) | 0.050[68] | 0.0041 | 1610 | 1610 | Galileo | Galilean |

| II | Europa♠ | /jʊəˈroʊpə/[69] |  | -1.4 | 3121.6 | 4799800 | 671100 | +3.5255 (+3d 12h 36m 40s) | 0.470[68] | 0.0090 | 1610 | 1610 | Galileo | Galilean |

| III | Ganymede♠ | /ˈɡænəmiːd/[70][71] |  | -2.1 | 5268.2 | 14819000 | 1070400 | +7.1556 | 0.200[68] | 0.0013 | 1610 | 1610 | Galileo | Galilean |

| IV | Callisto♠ | /kəˈlɪstoʊ/ |  | -1.2 | 4820.6 | 10759000 | 1882700 | +16.690 | 0.192[68] | 0.0074 | 1610 | 1610 | Galileo | Galilean |

| XVIII | Themisto† | /θəˈmɪstoʊ/ |  | 13.3 | ≈ 9 | ≈ 0.038 | 7398500 | +130.03 | 43.8 | 0.340 | 1975/2000 | 1975 | Kowal & Roemer/ Sheppard et al. | Themisto |

| XIII | Leda♣ | /ˈliːdə/ |  | 12.7 | 21.5 | ≈ 0.52 | 11146400 | +240.93 | 28.6 | 0.162 | 1974 | 1974 | Kowal | Himalia |

| LXXI | Ersa♣ | /ˈɜːrsə/ |  | 16.0 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 11401000 | +249.23 | 29.1 | 0.116 | 2018 | 2018 | Sheppard | Himalia |

| S/2018 J 2♣ | 16.5 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 11419700 | +249.92 | 28.3 | 0.152 | 2018 | 2022 | Sheppard | Himalia | |||

| VI | Himalia♣ | /hɪˈmeɪliə/ |  | 8.0 | 139.6 (150 × 120) | 420 | 11440600 | +250.56 | 28.1 | 0.160 | 1904 | 1905 | Perrine | Himalia |

| LXV | Pandia♣ | /pænˈdaɪə/ |  | 16.2 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 11481000 | +251.91 | 29.0 | 0.179 | 2017 | 2018 | Sheppard | Himalia |

| X | Lysithea♣ | /laɪˈsɪθiə/ |  | 11.2 | 42.2 | ≈ 3.9 | 11700800 | +259.20 | 27.2 | 0.117 | 1938 | 1938 | Nicholson | Himalia |

| VII | Elara♣ | /ˈɛlərə/ |  | 9.7 | 79.9 | ≈ 27 | 11712300 | +259.64 | 27.9 | 0.211 | 1905 | 1905 | Perrine | Himalia |

| S/2011 J 3♣ | 16.3 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 11716800 | +259.84 | 27.6 | 0.192 | 2011 | 2022 | Sheppard | Himalia | |||

| LIII | Dia♣ | /ˈdaɪə/ |  | 16.1 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.0034 | 12260300 | +278.21 | 29.0 | 0.232 | 2000 | 2001 | Sheppard et al. | Himalia |

| S/2018 J 4§ | 16.7 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 16328500 | +427.63 | 50.2 | 0.177 | 2018 | 2023 | Sheppard | Carpo | |||

| XLVI | Carpo§ | /ˈkɑːrpoʊ/ |  | 16.2 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 17042300 | +456.29 | 53.2 | 0.416 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Carpo |

| LXII | Valetudo± | /væləˈtjuːdoʊ/ |  | 17.0 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 18694200 | +527.61 | 34.5 | 0.217 | 2016 | 2018 | Sheppard | Valetudo |

| XXXIV | Euporie♦ | /ˈjuːpəriː/ |  | 16.3 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 19265800 | −550.69 | 145.7 | 0.148 | 2001 | 2002 | Sheppard et al. | Ananke |

| LV | S/2003 J 18♦ |  | 16.4 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 20336300 | −598.12 | 145.3 | 0.090 | 2003 | 2003 | Gladman | Ananke | |

| LX | Eupheme♦ | /juːˈfiːmiː/ |  | 16.6 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 20768600 | −617.73 | 148.0 | 0.241 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Ananke |

| S/2021 J 3♦ | 17.2 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 20776700 | −618.33 | 147.9 | 0.239 | 2021 | 2023 | Sheppard | Ananke | |||

| LII | S/2010 J 2♦ |  | 17.4 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 20793000 | −618.84 | 148.1 | 0.248 | 2010 | 2011 | Veillet | Ananke | |

| LIV | S/2016 J 1♦ |  | 17.0 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 20802600 | −618.49 | 144.7 | 0.232 | 2016 | 2017 | Sheppard | Ananke | |

| XL | Mneme♦ | /ˈniːmiː/ |  | 16.3 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 20821000 | −620.07 | 148.0 | 0.247 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard & Gladman | Ananke |

| XXXIII | Euanthe♦ | /juːˈænθiː/ |  | 16.4 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 20827000 | −620.44 | 148.0 | 0.239 | 2001 | 2002 | Sheppard et al. | Ananke |

| S/2003 J 16♦ |  | 16.3 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 20882600 | −622.88 | 148.0 | 0.243 | 2003 | 2003 | Gladman | Ananke | ||

| XXII | Harpalyke♦ | /hɑːrˈpæləkiː/ |  | 15.9 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.0034 | 20892100 | −623.32 | 147.7 | 0.232 | 2000 | 2001 | Sheppard et al. | Ananke |

| XXXV | Orthosie♦ | /ɔːrˈθoʊziː/ |  | 16.6 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 20901000 | −622.59 | 144.3 | 0.299 | 2001 | 2002 | Sheppard et al. | Ananke |

| XLV | Helike♦ | /ˈhɛləkiː/ |  | 16.0 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.0034 | 20915700 | −626.33 | 154.4 | 0.153 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Ananke |

| S/2021 J 2♦ | 17.3 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 20926600 | −625.14 | 148.1 | 0.242 | 2021 | 2023 | Sheppard | Ananke | |||

| XXVII | Praxidike♦ | /prækˈsɪdəkiː/ |  | 14.9 | 7 | ≈ 0.018 | 20935400 | −625.39 | 148.3 | 0.246 | 2000 | 2001 | Sheppard et al. | Ananke |

| LXIV | S/2017 J 3♦ |  | 16.5 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 20941000 | −625.60 | 147.9 | 0.231 | 2017 | 2018 | Sheppard | Ananke | |

| S/2021 J 1♦ | 17.3 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 20954700 | −627.14 | 150.5 | 0.228 | 2021 | 2023 | Sheppard | Ananke | |||

| S/2003 J 12♦ |  | 17.0 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 20963100 | −627.24 | 150.0 | 0.235 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Ananke | ||

| LXVIII | S/2017 J 7♦ | 16.6 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 20964800 | −626.56 | 147.3 | 0.233 | 2017 | 2018 | Sheppard | Ananke | ||

| XLII | Thelxinoe♦ | /θɛlkˈsɪnoʊiː/ | 16.3 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 20976000 | −628.03 | 150.6 | 0.228 | 2003 | 2004 | Sheppard & Gladman et al. | Ananke | |

| XXIX | Thyone♦ | /θaɪˈoʊniː/ |  | 15.8 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.0034 | 20978000 | −627.18 | 147.5 | 0.233 | 2001 | 2002 | Sheppard et al. | Ananke |

| S/2003 J 2♦ |  | 16.7 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 20997700 | −628.79 | 150.2 | 0.225 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Ananke | ||

| XII | Ananke♦ | /əˈnæŋkiː/ |  | 11.7 | 29.1 | ≈ 1.3 | 21034500 | −629.79 | 147.6 | 0.237 | 1951 | 1951 | Nicholson | Ananke |

| S/2022 J 3♦ | 17.4 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 21047700 | −630.67 | 148.2 | 0.249 | 2022 | 2023 | Sheppard | Ananke | |||

| XXIV | Iocaste♦ | /aɪəˈkæstiː/ |  | 15.5 | ≈ 5 | ≈ 0.0065 | 21066700 | −631.59 | 148.8 | 0.227 | 2000 | 2001 | Sheppard et al. | Ananke |

| XXX | Hermippe♦ | /hərˈmɪpiː/ |  | 15.5 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.0034 | 21108500 | −633.90 | 150.2 | 0.219 | 2001 | 2002 | Sheppard et al. | Ananke |

| LXX | S/2017 J 9♦ | 16.2 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 21768700 | −666.11 | 155.5 | 0.200 | 2017 | 2018 | Sheppard | Ananke | ||

| LVIII | Philophrosyne‡ | /fɪləˈfrɒzəniː/ | 16.7 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 22604600 | −702.54 | 146.3 | 0.229 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Pasiphae | |

| S/2016 J 3♥ | 16.7 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 22719300 | −713.64 | 164.6 | 0.251 | 2016 | 2023 | Sheppard | Carme | |||

| S/2022 J 1♥ | 17.0 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 22725200 | −738.33 | 164.5 | 0.257 | 2022 | 2023 | Sheppard | Carme | |||

| XXXVIII | Pasithee♥ | /ˈpæsəθiː/ |  | 16.8 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 22846700 | −719.47 | 164.6 | 0.270 | 2001 | 2002 | Sheppard et al. | Carme |

| LXIX | S/2017 J 8♥ |  | 17.1 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 22849500 | −719.76 | 164.8 | 0.255 | 2017 | 2018 | Sheppard | Carme | |

| S/2021 J 6♥ | 17.3 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 22870300 | −720.97 | 164.9 | 0.271 | 2021 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | Carme | |||

| S/2003 J 24♥ | 16.6 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 22887400 | −721.60 | 164.5 | 0.259 | 2003 | 2021 | Sheppard et al. | Carme | |||

| XXXII | Eurydome‡ | /jʊəˈrɪdəmiː/ |  | 16.2 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 22899000 | −717.31 | 149.1 | 0.294 | 2001 | 2002 | Sheppard et al. | Pasiphae |

| LVI | S/2011 J 2‡ | 16.8 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 22909200 | −718.32 | 151.9 | 0.355 | 2011 | 2012 | Sheppard | Pasiphae | ||

| S/2003 J 4‡ |  | 16.7 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 22926500 | −718.10 | 148.2 | 0.328 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Pasiphae | ||

| XXI | Chaldene♥ | /kælˈdiːniː/ |  | 16.0 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.0034 | 22930500 | −723.71 | 164.7 | 0.265 | 2000 | 2001 | Sheppard et al. | Carme |

| LXIII | S/2017 J 2♥ |  | 16.4 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 22953200 | −724.71 | 164.5 | 0.272 | 2017 | 2018 | Sheppard | Carme | |

| XXVI | Isonoe♥ | /aɪˈsɒnoʊiː/ |  | 16.0 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.0034 | 22981300 | −726.27 | 164.8 | 0.249 | 2000 | 2001 | Sheppard et al. | Carme |

| S/2022 J 2♥ | 17.6 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 23013800 | −781.56 | 164.7 | 0.265 | 2022 | 2023 | Sheppard | Carme | |||

| S/2021 J 4♥ | 17.4 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 23019700 | −728.28 | 164.6 | 0.265 | 2021 | 2023 | Sheppard | Carme | |||

| XLIV | Kallichore♥ | /kəˈlɪkəriː/ | 16.3 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23021800 | −728.26 | 164.8 | 0.252 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Carme | |

| XXV | Erinome♥ | /ɛˈrɪnəmiː/ |  | 16.0 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 23032900 | −728.48 | 164.4 | 0.276 | 2000 | 2001 | Sheppard et al. | Carme |

| XXXVII | Kale♥ | /ˈkeɪliː/ |  | 16.3 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23052600 | −729.64 | 164.6 | 0.262 | 2001 | 2002 | Sheppard et al. | Carme |

| LVII | Eirene♥ | /aɪˈriːniː/ | 15.8 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.0034 | 23055800 | −729.84 | 164.6 | 0.258 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Carme | |

| XXXI | Aitne♥ | /ˈeɪtniː/ |  | 16.0 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 23064400 | −730.10 | 164.6 | 0.277 | 2001 | 2002 | Sheppard et al. | Carme |

| XLVII | Eukelade♥ | /juːˈkɛlədiː/ |  | 16.0 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.0034 | 23067400 | −730.30 | 164.6 | 0.277 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Carme |

| XLIII | Arche♥ | /ˈɑːrkiː/ |  | 16.2 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 23097800 | −731.88 | 164.6 | 0.261 | 2002 | 2002 | Sheppard | Carme |

| XX | Taygete♥ | /teɪˈɪdʒətiː/ |  | 15.6 | ≈ 5 | ≈ 0.0065 | 23108000 | −732.45 | 164.7 | 0.253 | 2000 | 2001 | Sheppard et al. | Carme |

| S/2016 J 4‡ | 17.3 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 23113800 | −727.01 | 147.1 | 0.294 | 2016 | 2023 | Sheppard | Pasiphae | |||

| LXXII | S/2011 J 1♥ | 16.7 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23124500 | −733.21 | 164.6 | 0.271 | 2011 | 2012 | Sheppard | Carme | ||

| XI | Carme♥ | /ˈkɑːrmiː/ |  | 10.6 | 46.7 | ≈ 5.3 | 23144400 | −734.19 | 164.6 | 0.256 | 1938 | 1938 | Nicholson | Carme |

| L | Herse♥ | /ˈhɜːrsiː/ | 16.5 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23150500 | −734.52 | 164.4 | 0.262 | 2003 | 2003 | Gladman et al. | Carme | |

| LXI | S/2003 J 19♥ | 16.6 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23156400 | −734.78 | 164.7 | 0.265 | 2003 | 2003 | Gladman | Carme | ||

| LI | S/2010 J 1♥ |  | 16.5 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23189800 | −736.51 | 164.5 | 0.252 | 2010 | 2011 | Jacobson et al. | Carme | |

| S/2003 J 9♥ |  | 16.9 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 23199400 | −736.86 | 164.8 | 0.263 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Carme | ||

| LXVI | S/2017 J 5♥ | 16.5 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23206200 | −737.28 | 164.8 | 0.257 | 2017 | 2018 | Sheppard | Carme | ||

| LXVII | S/2017 J 6‡ | 16.6 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23245300 | −733.99 | 149.7 | 0.336 | 2017 | 2018 | Sheppard | Pasiphae | ||

| XXIII | Kalyke♥ | /ˈkæləkiː/ |  | 15.4 | 6.9 | ≈ 0.017 | 23302600 | −742.02 | 164.8 | 0.260 | 2000 | 2001 | Sheppard et al. | Carme |

| XXXIX | Hegemone‡ | /həˈdʒɛməniː/ | 15.9 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.0014 | 23348700 | −739.81 | 152.6 | 0.358 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Pasiphae | |

| S/2018 J 3♥ | 17.3 | ≈ 1 | ≈ 0.000052 | 23400300 | −747.02 | 164.9 | 0.268 | 2018 | 2023 | Sheppard | Carme | |||

| S/2021 J 5♥ | 16.8 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23414600 | −747.74 | 164.9 | 0.272 | 2021 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | Carme | |||

| VIII | Pasiphae‡ | /pəˈsɪfeɪiː/ |  | 10.1 | 57.8 | ≈ 10 | 23468200 | −743.61 | 148.4 | 0.412 | 1908 | 1908 | Melotte | Pasiphae |

| XXXVI | Sponde‡ | /ˈspɒndiː/ |  | 16.7 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23543300 | −748.29 | 149.3 | 0.322 | 2001 | 2002 | Sheppard et al. | Pasiphae |

| S/2003 J 10♥ |  | 16.9 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23576300 | −755.43 | 164.4 | 0.264 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Carme | ||

| XIX | Megaclite‡ | /ˌmɛɡəˈklaɪtiː/ |  | 15.0 | ≈ 5 | ≈ 0.0065 | 23644600 | −752.86 | 149.8 | 0.421 | 2000 | 2001 | Sheppard et al. | Pasiphae |

| XLVIII | Cyllene‡ | /səˈliːniː/ | 16.3 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23654700 | −751.97 | 146.8 | 0.419 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Pasiphae | |

| IX | Sinope‡ | /səˈnoʊpiː/ |  | 11.1 | 35 | ≈ 2.2 | 23683900 | −758.85 | 157.3 | 0.264 | 1914 | 1914 | Nicholson | Pasiphae |

| LIX | S/2017 J 1‡ |  | 16.8 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23744800 | −756.41 | 145.8 | 0.328 | 2017 | 2017 | Sheppard | Pasiphae | |

| XLI | Aoede‡ | /eɪˈiːdiː/ | 15.6 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.0034 | 23778200 | −761.42 | 155.7 | 0.436 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Pasiphae | |

| XXVIII | Autonoe‡ | /ɔːˈtɒnoʊiː/ |  | 15.5 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.0034 | 23792500 | −761.00 | 150.8 | 0.330 | 2001 | 2002 | Sheppard et al. | Pasiphae |

| XVII | Callirrhoe‡ | /kəˈlɪroʊiː/ |  | 14.0 | 9.6 | ≈ 0.046 | 23795500 | −758.87 | 145.1 | 0.297 | 1999 | 2000 | Scotti et al. | Pasiphae |

| S/2003 J 23‡ |  | 16.6 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 23829300 | −760.00 | 144.7 | 0.313 | 2003 | 2004 | Sheppard | Pasiphae | ||

| XLIX | Kore‡ | /ˈkɔːriː/ |  | 16.6 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.00042 | 24205200 | −776.76 | 141.5 | 0.328 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard | Pasiphae |

Exploration

Nine spacecraft have visited Jupiter. The first were Pioneer 10 in 1973, and Pioneer 11 a year later, taking low-resolution images of the four Galilean moons and returning data on their atmospheres and radiation belts.[72] The Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes visited Jupiter in 1979, discovering the volcanic activity on Io and the presence of water ice on the surface of Europa. Ulysses further studied Jupiter's magnetosphere in 1992 and then again in 2000.

The Galileo spacecraft was the first to enter orbit around Jupiter, arriving in 1995 and studying it until 2003. During this period, Galileo gathered a large amount of information about the Jovian system, making close approaches to all of the Galilean moons and finding evidence for thin atmospheres on three of them, as well as the possibility of liquid water beneath the surfaces of Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. It also discovered a magnetic field around Ganymede.

Then the Cassini probe to Saturn flew by Jupiter in 2000 and collected data on interactions of the Galilean moons with Jupiter's extended atmosphere. The New Horizons spacecraft flew by Jupiter in 2007 and made improved measurements of its satellites' orbital parameters.

In 2016, the Juno spacecraft imaged the Galilean moons from above their orbital plane as it approached Jupiter orbit insertion, creating a time-lapse movie of their motion.[73] With a mission extension, Juno has since begun close flybys of the Galileans, flying by Ganymede in 2021 followed by Europa and Io in 2022. It flew by Io again in late 2023 and once more in early 2024.

See also

Notes

References

External links