North Germanic peoples, Nordic peoples[1] and in a medieval context Norsemen,[2] were a Germanic linguistic group originating from the Scandinavian Peninsula.[3] They are identified by their cultural similarities, common ancestry and common use of the Proto-Norse language from around 200 AD, a language that around 800 AD became the Old Norse language, which in turn later became the North Germanic languages of today.[4]

The North Germanic peoples are thought to have emerged as a distinct people in what is now southern Sweden in the early centuries AD.[5] Several North Germanic tribes are mentioned by classical writers in antiquity, in particular the Swedes, Danes, Geats, Gutes and Rugii. During the subsequent Viking Age, seafaring North Germanic adventurers, commonly referred to as Vikings, raided and settled territories throughout Europe and beyond, founding several important political entities and exploring the North Atlantic as far as North America. Groups that arose from this expansion include the Normans, the Norse–Gaels and the Rus' people. The North Germanic peoples of the Viking Age went by various names among the cultures they encountered, but are generally referred to as Norsemen.[6]

With the end of the Viking Age in the 11th century, the North Germanic peoples were converted from their native Norse paganism to Christianity, while their previously tribal societies were centralized into the modern kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden.[7][8][6]

Modern linguistic groups that descended from the North Germanic peoples are the Danes, Icelanders, Norwegians, Swedes, and Faroese.[2][9][10][11] These groups are often collectively referred to as Scandinavians,[9][11] although Icelanders and the Faroese[12] are sometimes excluded from that definition.[13][3]

Names

Ethnonyms

Although the early North Germanic peoples definitely had a common identity, it is uncertain if they had a common ethnonym.[14] Their common identity was rather expressed through the geographical and linguistic Old Norse terms Norðrlǫnd 'northern lands' and dǫnsk tunga 'Danish tongue'.[14] Most early Scandinavians would however primarily identify themselves with their region of origin.[15] However, the Old Norse term Nordmenn, usually applied for Norwegians, was sometimes applied to all Old Norse speakers.[15]

Exonyms

In the early medieval period, as today, Vikings was a common term for North Germanic raiders, especially in connection with raids and monastic plundering in continental Europe and the British Isles. In modern times, the term is often applied to all North Germanic peoples of the Middle Ages, including raiders and non-raiders,[15] although such use is controversial.[16] From the Old Norse language, the term norrœnir menn (northern men), has given rise to the English name Norsemen, which is sometimes used for the pre-Christian North Germanic peoples.[15][17][18] In scholarship, however, the term Norsemen generally refers only to early Norwegians.[19]

The North Germanic peoples were known by many names by those they encountered. They were known as Ascomanni (Ashmen) by the Germans, and Dene (Danes) or heathens by the Anglo-Saxons.[15][20][17][21] The Old Frankish word Nortmann 'Northman' was Latinised as Normanni and then entered Old French as Normands, whence the name of the Normans and of Normandy, which was conquered from the Franks by Vikings in the 10th century.[15] The Old Irish terms Finngall 'white foreigner' and Dubgall 'black foreigner' were used by the Irish for Norwegian and Danish Vikings, respectively.[15][20][17] Dubliners called them Ostmen (East-people), and the name Oxmanstown (an area in central Dublin; the name is still current) comes from one of their settlements; they were also known as Lochlannaig 'lake-people'.[15]

The Slavs, Finns, Muslims, Byzantines and other peoples of the east knew them as the Rus' or Rhōs, probably derived from various uses of rōþs-, i.e. "related to rowing", or from the area of Roslagen in east-central Sweden, where most of the Vikings who visited the Slavic lands originated.[15][17] The Arabs of Spain also knew them as al-Majus (fire-worshippers), although they used this term rather for the Basques.[17] After the Rus' established Kievan Rus' and gradually merged with the Slavic population, the North Germanic people in the east become known as Varangians (ON: Væringjar, meaning "sworn men"), after the bodyguards of the Byzantine known as the Varangian Guard.[22]

In modern scholarship, the terms Scandinavians[11][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31] and Norsemen[32][33][34] are common synonyms for North Germanic peoples.[2][9][13][35] As such, Scandinavians is generally applied to modern North Germanic peoples, while Norsemen is sometimes applied to pagan pre-modern North Germanic peoples.[36][37][34][38]

History

Prehistory

The Battle Axe culture, a local variant of the Corded Ware culture, which was itself an offshoot of the Yamnaya culture, emerged in southern Scandinavia in the early 3rd millennium BC. Modern-day Scandinavians have been found to carry more ancestry from the Yamnaya culture than any other population in Europe.[39] While previous inhabitants of Scandinavia have been found to be mostly carriers of haplogroup I, the emergence of the Battle Axe culture in Scandinavia is characterized by the appearance of new lineages such as haplogroup R1a and haplogroup R1b.[40] The Proto-Germanic language is ultimately thought to have emerged from the Battle Axe culture, possibly through its superimposition upon the earlier megalithic cultures of the area.[41] The Germanic tribal societies of Scandinavia were thereafter surprisingly stable for thousands of years.[42]

Scandinavia is considered the only area in Europe where the Bronze Age was significantly delayed for a whole region.[43] The period was nevertheless characterized by the independent development of new technologies, with the peoples of southern Scandinavia developing a culture with its own characteristics, indicating the emergence of a common cultural heritage.[43] When bronze was finally introduced, its importance was rapidly established, leading to the emergence of the Nordic Bronze Age.[43] The Nordic Bronze Age is closely genetically related to the Beaker and Unetice cultures of Continental Europe, and even the Sintashta and Andronovo cultures of the Eurasian Steppe, with whom it also shares numerous cultural characteristics.[44]

Ancient history

During the Iron Age the peoples of Scandinavia were engaged in the export of slaves and amber to the Roman Empire, receiving prestige goods in return. This is attested by artifacts of gold and silver that have been found at rich burials from the period. North Germanic tribes, chiefly Swedes, were probably engaged as middlemen in the slave trade along the Baltic coast between Balts and Slavs and the Roman Empire. The North Germanic tribes at the time were skilled metal and leather workers, which supplemented their trade in iron and amber.[42][45] In his book Germania, the Roman historian Tacitus mentions the Swedes (Suiones) as being governed by powerful rulers and excelling at seafaring.[45] From a very early time, Germanic tribes are thought to have interacted with and possibly settled in the Baltic states, in which they would leave a profound influence, particularly on the ancient Estonians.[25]

During the Iron Age various Germanic tribes migrated from Scandinavia to East-Central Europe. This included the Rugii, Goths, Gepids, Vandals, Burgundians and others.[41][46][47] The Rugii might have originated in Western Norway (Rogaland).[48] The migrations of most of these tribes is thought to have occurred around 200 BC, though the Vandals might have migrated earlier.[47] According to the historian Procopius, these tribes were distinguished by their height, fair complexion, physical attractiveness and common cultural characteristics, suggesting a common origin.[49] Because of the large number of Germanic tribes that traced their origin to Scandinavia, the region became known by Early Medieval historians as the Factory of Nations (Latin: Officina Gentium) or Womb of Nations (Latin: Vagina Nationum).[47][50] The early Germanic tribes that migrated from Scandinavia became speakers of East Germanic dialects. Though these tribes were probably indistinguishable from later North Germanic tribes at the time of their migration, the culture and language of North and East Germanic tribes would thereafter take divergent lines of development.[23] Another Germanic tribe which claimed Scandinavian origins were the Lombards.[51]

The region of the north, in proportion as it is removed from the heat of the sun and is chilled with snow and frost, is so much the more healthful to the bodies of men and fitted for the propagation of nations, just as, on the other hand, every southern region, the nearer it is to the heat of the sun, the more it abounds in diseases and is less fitted for the bringing up of the human race.[52]

It is likely that Proto-Norse emerged as a separate Germanic dialect around the 1st century.[24] The ethnogenesis of the North Germanic peoples is thought to have occurred in Sweden.[5] Sweden was the home of the earliest attestations of North Germanic culture, and the later North Germanic tribes of Norway and Denmark originated in Sweden.[5] Archaeological evidence suggests that the North Germanic tribes at the time constituted one of five main tribal groups among the Germanic peoples, the others being North Sea Germanic tribes (Frisians, Saxons and Angles), Weser–Rhine Germanic tribes (Hessians, Franks), Elbe Germanic tribes (Lombards, Alemanni, Bavarians) and Oder-Vistula Germanic tribes (Goths, Vandals, Burgundians).[26]

The southward expansion of the East Germanic tribes pushed many other Germanic and Iranian peoples towards the Roman Empire, spawning the Marcomannic Wars in the 2nd century AD.[41] Another East Germanic tribe were the Herules, who according to 6th century historian Jordanes were driven from modern-day Denmark by the Danes, who were an offshoot of the Swedes.[53] The migration of the Herules is thought to have occurred around 250 AD.[54] The Danes would eventually settle all of Denmark, with many its former inhabitants, including the Jutes and Angles, settling Britain, becoming known as the Anglo-Saxons.[55] The Old English story Beowulf is a testimony to this connection.[56] Meanwhile, Norway was inhabited by a large number of North Germanic tribes and divided into a score of petty kingdoms.

Among the early North Germanic peoples, kinship ties played an important role in social organization. Society was divided into three classes, chieftains, free men and slaves (thralls). Free men were those who owned and farmed the land. Religious leaders, merchants, craftsmen and armed retainers of chieftains (housecarls) were not confined to any specific class. Women had considerable independence compared to other parts of Europe. Legislative and judicial power lay in the hands of the free men at a popular assembly known as the Thing.[42] Their legal system was closely related to those of other Germanic peoples.[57] Dwellings were built according to methods that had changed little since the neolithic. A chieftain typically had his seat of power in a mead hall, where lavish feasts for his followers were held. Merchants frequently operated through joint financial ventures, and some legal disputes were solved through single combat. Men of prominence were generally buried along with their most prized possessions, including horses, chariots, ships, slaves and weapons, which were supposed to follow them into the afterlife.[58]

Though the economy was primarily based on farming and trade, the North Germanic tribes practiced a warrior culture similar to related Germanic peoples and the ancient Celts.[42] Warfare was generally carried out in small war bands, whose cohesiveness generally relied upon the loyalty between warriors and their chiefs. Loyalty was considered a virtue of utmost importance in early North Germanic society.[22] A fabled elite group of ferocious North Germanic warriors were the berserkers. The North Germanic tribes of these period also excelled at shipbuilding and maritime warfare.[58]

The North Germanic tribes practiced Norse paganism, a branch of Germanic paganism, which ultimately stems from Proto-Indo-European religion.[59] Religion was typically practiced at hallowed outdoor sites, but there is also reference to temples, where sacrifices were held. The best known of these was the Temple at Uppsala. Their art was intimately intertwined with their religion. Their stories and myths were typically inscribed on runestones or transmitted orally by skalds.[58] According to North Germanic belief, those who died in battle gained admittance to Folkvang, Freya's Hall, and above all to Valhalla, a majestic hall presided over by Odin, ruler of Asgard according to their cosmology and the chief god in the North Germanic pantheon. Runes, the Germanic form of writing, was associated with Odin and magic.[60] The thunder god Thor was popular with the North Germanic common people.[61]

By the 3rd century there seems to have been a disruption of trade, possibly due to attacks from tribes in periphery. In the 4th and 5th centuries, larger settlements were established in southern Scandinavia, indicating a centralization of power. Numerous strongholds were also being built, indicating a need to defend against attacks. Deposits of weapons in bogs from this period suggest the presence of a warrior aristocracy.[42] The Gutes of Gotland are in later Old Norse literature considered indistinguishable from the Goths, who in the 3rd and 4th centuries wrested control of the Pontic Steppe from the Iranian nomads. The Goths were the only non-nomadic people to ever acquire a dominant position on the Eurasian steppe, and their influence on the early Slavs must have been considerable.[62] When the Huns invaded these territories, the North Germanic legends recall that the Gizur of the Geats came to the aid of the Goths in an epic conflict. Rich Eastern Roman finds made in Gotland and southern Sweden from this period are a testimony to this connection.[42]

Archaeological evidence suggest that a warrior elite continued to dominate North Germanic society into the Early Middle Ages.[42] The royal dynasty of the Swedes, the Yngling, was founded in the 5th century. Based at Gamla Uppsala, the Ynglings would come to dominate much of Scandinavia.[42] The importance of this dynasty for the North Germanic peoples is attested by the fact that the later Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson begins his history of the Norse peoples, the Heimskringla, with the legends of ancient Sweden.[5]

Early Middle Ages

Around 510, the Herules returned to their home in southern Sweden following centuries of migrations throughout Europe, after their kingdom had been overwhelmed by the Lombards.[53] Their name has been connected to the word erilaz attested in Elder Futhark inscriptions and the title Earl.

In his book Getica, the 6th century Gothic historian Jordanes presents a detailed description of the various peoples inhabiting Scandinavia (Scandza), a land "not only inhospitable to men but cruel even to wild beasts."[63] Jordanes wrote that the Scandinavians were distinguished from other Germanic peoples by being of larger physical stature and more warlike. The most numerous of these tribes were the Swedes and the Danes, who were an offshoot of the Swedes. Another North Germanic tribe were the Ranii, whose king Rodulf left Scandinavia for Ostrogothic Italy and became a companion of Theoderic the Great.[63]

Each of these countries was like a mighty hive, which, by the vigour of propagation and health of climate, growing too full of people, threw out some new swarm at certain periods of time, that took wing, and sought out some new abode, expelling or subduing the old inhabitants, and seating themselves in their rooms.[64]

North Germanic vikings might have been engaged in naval raids in Western Europe as early as the 6th century. Between 512 and 520, Frankish annals and the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf claim that a certain Hygelac or Hugleik, King of the Geats, made a raid in the Rhineland somewhere between 512 and 520. Carrying off great booty, Hygelac was allegedly defeated and killed before he could return to Scandinavia. Before the 7th century AD, Norwegian seafarers had settled Shetland.[65] During this time the Frisians were the foremost rivals of the Scandinavians for naval supremacy in the North Sea.[66] By the 8th century, the Swedes, by far the most advanced of the North Germanic peoples, had established colonial settlements in modern Estonia, Latvia and the southern shores of Lake Ladoga and Lake Onega in present-day Russia.[67][68] The settlement of Grobiņa in Latvia and the Salme ships of Saaremaa, Estonia, are testimony to this expansion. In this period the entire eastern Baltic Sea came to be dominated by a homogenous warrior culture derived from Sweden, in which Old Norse served as the lingua franca.[69]

Viking Age

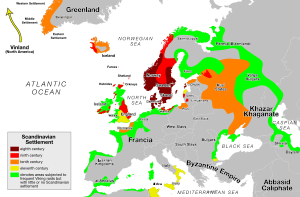

In the late 8th century North Germanic tribes embarked on a massive expansion in all the directions. This was the start of the Viking Age, which lasted until 1066 AD. This expansion is considered the last of the great North Germanic migrations.[23] These seafaring traders, settlers and warriors are commonly referred to as Vikings.[16][36][70][71][72][73][74] The North Germanic peoples of the Viking Age as a whole are sometimes referred to as Norsemen.[6][15][17][75][76][33][13][37][36][73][77][78][38][18][34] However, the term Norsemen is often used only for early Norwegians,[19][79] or as a synonym for Vikings.[13] Though the early Scandinavians did not have an ethnonym for themselves, they certainly had a common identity, which has survived among their descendants up to the present day.[14]

The cause of this expansion is often thought to have been overpopulation.[80][70] Other explanations include political tensions, disruption of trade with the Abbasid Caliphate, or vengeance against massacres committed against the pagan Saxons by the Carolingian Empire.[7] The prospect of a Carolingian invasion of Denmark itself created much fear and resentment among the Scandinavians.[81] The destruction of the naval powers of the Frisians by Charlemagne in the 8th century also probably played a key role in facilitating the naval dominance of the Scandinvians.[66] The centralization of power that was carried out by Harald Fairhair and other powerful Scandinavian rulers drove many warlike men into exile abroad.[82] By this time North Germanic military units were typically larger than in previous centuries.[58][83] During this time the North Germanic peoples spoke Old Norse.[24][27][73][84]

The Vikings raided and settled various parts in the British Isles, in particular the area around the Irish Sea and Scotland, where they became known as the Norse–Gaels. The Uí Ímair dynasty acquired a prominent position among these Scandinavians, establishing the Kingdom of the Isles. These Vikings, mostly Norwegians, came close to completely conquering Ireland until they were defeated by the Irish at the Battle of Clontarf.[85] They would nevertheless remain firmly established in Ireland for generations afterwards, in particular the cities of Dublin, Waterford and Limerick.[85] In the 9th century, Danish Vikings gained control of a part of eastern England, which became known as the Danelaw.[7] England was the part of Europe most heavily subjected to Viking attacks, and it is likely that the Scandinavians would have gained control of all of England if not for the successful resistance of Alfred the Great.[85] In the early 11th century, England temporarily became part of the North Sea Empire of Danish king Cnut the Great from 1016 to 1042.[85]

Vikings were also active in both east and west Francia. There were extensive raids in the Rhineland, and Hamburg was burned in 845. In the early 10th century, a group of Vikings under the leadership of Rollo settled in Rouen, France, and established the Duchy of Normandy. The descendants of these Vikings, known as the Normans, would in the 11th century conquer England, Southern Italy, and North Africa, and play a leading role in launching the Crusades.[7][86] Sub-groups of the Normans include Anglo-Normans, Scoto-Normans, Cambro-Normans, Hiberno-Normans and Italo-Normans.

Some Vikings raided in Spain, and sailed through the Strait of Gibraltar and pillaged the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea.[87]

In the east the Danish Viking were active in raiding the Wends. The most famous colonies created by these Vikings was Jomsborg in modern Pomerania, which became the base of the Jomsvikings.[85]

The Swedes were particularly active in Eastern Europe, where they were known as the Rus'.[70][22] They were engaged in extensive trade with the Byzantine Empire and the Abbasid Caliphate, launching raids on Constantinople and expeditions in the Caspian Sea.[85] The Rus' are described in detail by the Arab traveller Ahmad ibn Fadlan, who described them as tall, blond and the most "perfect physical specimens" he had ever seen.[88] In the 9th century, the Viking Rurik is believed to have founded the Rurik dynasty, which eventually developed into Kievan Rus'. The North Germanic elite of this state were known as the Rus'. In the 10th century, the Rus', in cooperation with surviving Crimean Goths, destroyed the Khazar Khaganate and emerged as the dominant power in Eastern Europe.[89] By the 11th century, the Rus' had converted to Eastern Orthodoxy and were gradually merging with the local East Slavic population, becoming known as the Russians.[22][85] The North Germanic diaspora in the area were thereafter called Varangians.[7] Many of them served in the Varangian Guard, the personal bodyguard of the Byzantine emperors.[70] Among the prominent Scandinavians who served in the Varangian Guard were Norwegian king Harald Hardrada.[22][85]

While the Danes and Swedes were active in Francia and Russia respectively, North Germanic tribes from Norway were actively exploring the North Atlantic.[70] These Vikings were the first sailors in naval history to venture out into the open sea.[90] This initially resulted in the colonization of the Shetland Islands, Orkney Islands, the Faroese Islands and Iceland.[7] The most important Norse colony was the settlement in Iceland, which became a haven for Scandinavians who sought to preserve their traditional way of life and independence of central authority.[91] The literary heritage of the Icelanders is indispensable for the modern understanding of early North Germanic history and culture.[92] In the late 10th century, the Icelandic explorer Erik the Red discovered Greenland and supervised the Norse settlement of the island.[85] His son Leif later made the first documented trans-oceanic voyage in history and thereafter supervised the attempted Norse colonization of North America.[93]

Later history

While Vikings were raiding the rest of Europe, their own Scandinavian homeland was undergoing increasing centralization. This is evidenced by the number of larger settlements being built. Some of these settlements became seats for royal mints and bishoprics.[7]

By the mid-11th century, the North Germanic tribes had been converted from paganism to Christianity and were under the rule of centralized states. These states were the kingdoms of Norway, Sweden and Denmark.[7][8] The Scandinavian settlements in Greenland disappeared in the 15th century.[85]

Legacy

Modern groups descended from the North Germanic peoples are the Danes, Faroese people, Icelanders,[32] Norwegians[94] and Swedes.[95][2][9][10][11][96][35][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106] These groups are often referred to as Scandinavians,[3][13][16][29][77] although Icelanders and the Faroese, and even the Danes,[12] are sometimes not included as Scandinavians.[3][13][96][101] North Germanic peoples are sometimes called Nordic peoples by historians.[1][107][108] Along with the Germans, the English and the Dutch, they constitute one of the main branches of the Germanic peoples.[109][110][111]

With the rise of romantic nationalism in the 19th century, many prominent figures throughout Scandinavia became adherents of Scandinavism, which called for the unification of all North Germanic lands.[112] Both during the First Schleswig War and the Second Schleswig War between Denmark and Germany in the 19th century, large numbers of Swedes fought for Denmark to counter a perceived German threat against the North Germanic peoples.[113] In Norway, many prominent public figures favoured pan-Germanism from the mid-19th century, seeking to create a pan-Germanic state in unity with other "Germanic tribes". Pan-Germanism lost currency in Norway in 1943, when the Axis Powers were being pushed back on Eastern Front in the midst of World War II.[112]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

References

- Amory, Patrick (2003). People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489–554. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521526357.

- Baldi, Philip (1995). An Introduction to the Indo-European Languages. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0809310913.

- Barbour, Stephen; Stevenson, Patrick (1990). Variation in German: A Critical Approach to German Sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521357043.

- Berlitz (1 June 2015). Berlitz: Norway Pocket Guide. Apa Publications (UK). ISBN 978-1780048598.

- Bolling, George Melville; Bloch, Bernard (1968). Language. Linguistic Society of America.

- Bruce, Alexander M. (2014). Scyld and Scef: Expanding the Analogues. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317944218.

- Brøndsted, Johannes (1965). The Vikings. Penguin Books.

- Bury, John Bagnell (1964). The Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 2. The University Press.

- Chapman and Hall (1916). The Fortnightly Review, Volume 105. Chapman and Hall.

- Clarke, Hyde (1873). A Short Handbook of the Comparative Philology. Lockwood.

- Christiansen, Eric (2008). Norsemen in the Viking Age. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470692769.

- Clifford, John H. (1914). The Standard History of the World, by Great Historians. The University Society Inc.

- Collier (1921). Contemporary World Regional Geography: Global Connections, Local Voices. Vol. 9. Cambridge University Press.

- Daly, Kathleen N. (1976). Norse Mythology A to Z. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438128016.

- Davies, Norman (1999). The Isles: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198030737.

- DeAngelo, Jeremy (2010). "The North and the Depiction of the "Finnar" in the Icelandic Sagas". Scandinavian Studies. 82 (3): 257–286. doi:10.2307/25769033. JSTOR 25769033. S2CID 159972559.

- D'Epiro, Peter (2010). The Book of Firsts: 150 World-Changing People and Events, from Caesar Augustus to the Internet. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0307476661.

- Diringer, David (1948). The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind. Philosophical Library.

- Donaldson, Bruce C. (1983). Dutch: a linguistic history of Holland and Belgium. M. Nijhoff. ISBN 978-9024791668.

- Fee, Christopher R. (2011). Mythology in the Middle Ages: Heroic Tales of Monsters, Magic, and Might: Heroic Tales of Monsters, Magic, and Might. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0313027253.

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2009). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1405188968.

- Gall, Timothy L.; Hobby, Jeneen (2009). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life: Europe. Gale. ISBN 978-1414464305.

- Myers, Philip Van Ness (1894). Ancient History for Colleges and High Schools. Vol. 1. Ginn.

- Gordon, Eric Valentine; Taylor, A. R. (1962). An Introduction to Old Norse. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198111054.

- Helle, Knut; Kouri, E. I. [in Finnish]; Oleson, Jens I. [in Danish] (2003). The Cambridge History of Scandinavia, Edition 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521472999.

- Iowa Council of Teachers of English (1967). Iowa English Yearbook, Issue 1-6.

- Johnston, Ruth A. (2005). A Companion to Beowulf. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313332241.

- Jones, Gwyn (2001). A History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192801340.

- Jordanes (551). The Origin and Deeds of the Goths. Translated by Mierow, Charles C.

- Grosvenor, Edwin A. (December 1918). "The Races of Europe". National Geographic. XXXIV (6). National Geographic Society: 441–536.

- Herbermann, Charles George (1913). The Catholic encyclopedia: an international work of reference on the constitution, doctrine, discipline, and history of the Catholic church, Volume 7. Universal Knowledge Foundation. p. 615.

- Höffe, Otfried (2007). Democracy in an Age of Globalisation. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1402056628.

- Katzner, Kenneth; Miller, Kirk (2002). The Languages of the World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134532889.

- Kendrick, Thomas Downing (1930). A History of the Vikings. Barnes & Noble.

- Kennedy, Arthur Garfield (1963). "The Indo-European Language Family". In Lee, Donald Woodward (ed.). English Language Reader: Introductory Essays and Exercises. Dodd, Mead.

- Kristinsson, Axel (2010). Expansions: Competition and Conquest in Europe Since the Bronze Age. ReykjavíkurAkademían. ISBN 978-9979992219.

- Lawrence, William Witherle (1967). Beowulf and Epic Tradition. Hafner.

- Leach, Henry Goddard (1939). The American-Scandinavian Review. American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- Leeming, David A. (2014). The Handy Mythology Answer Book. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-1578595211.

- Logan, F. Donald (1963). The Vikings in History. Routledge. ISBN 1136527095.

- Logan, F. Donald (2013). The Vikings in History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-52709-8. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Luscombe, David; Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2004). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 4, C.1024-c.1198. Cambridge University Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-0521414111.

- Mägi, Marika (17 May 2018). In Austrvegr: The Role of the Eastern Baltic in Viking Age Communication across the Baltic Sea. BRILL. p. 154. ISBN 978-90-04-36381-6.

- Mallory, J. P. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1884964982.

- Marshall Cavendish (2010). World and Its Peoples. ISBN 978-0761478973.

- Mawer, Allen (1913). The Vikings. The University Press.

- McGraw-Hill Higher Education (2007). Contemporary World Regional Geography: Global Connections, Local Voices. ISBN 978-0072826838.

- McLaughlin, John Cameron (1970). Aspects of the history of English. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 9780030786600.

- McTurk, Rory (2008). A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1405137386.

- Merriam-Webster, Inc (1995). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. ISBN 978-0877790426.

- Moberg, Vilhelm (1972). History of the Swedish people: from prehistory to the Renaissance. Pantheon. ISBN 978-0394481920.

- Ostergren, Robert Clifford; Le Boss, Mathias (2011). The Europeans: A Geography of People, Culture, and Environment. Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1609181406.

- Oxenstierna, Eric (1967). The World of the Norsemen. Nordgermanen.English. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Patrick, David; Geddie, William (1921). Chambers's Encyclopaedia: A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge. Vol. 10. W. & R. Chambers.

- Paul the Deacon (1974). History of the Lombards. ISBN 978-0812210798.

- Rand McNally (1944). Rand McNally World Atlas.

- Ränk, Gustav (1976). Old Estonia, The People and Culture. Indiana University. ISBN 9780877501909.

- Sawyer, Peter (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192854346.

- van der Sijs, Nicoline (2009). Cookies, Coleslaw, and Stoops: The Influence of Dutch on the North American Languages. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-9089641243.

- Simpson, Jacqueline (1980). The Viking World. Batsford. ISBN 0713407778.

- Smith, Jeremy J. (2006). Essentials of Early English: Old, Middle and Early Modern English. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134292431.

- Smith, Thomas Alford (1913). A Geography of Europe. Macmillan.

- Spaeth, John Duncan Ernst (1921). Old English Poetry. Princeton University Press.

- Temple, William (1757). The Works of Sir William Temple Bart, Volume 3.

- Thompson, Stith (1995). Our Heritage of World Literature. Cordon Company. ISBN 978-0809310913.

- Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel; Drout, Michael D. C. (2002). Beowulf and the critics. Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. ISBN 978-0866982900.

- Vasiliev, Alexander A. (1936). The Goths in the Crimea. Medieval Academy of America.

- Wade, Herbert Treadwell (1930). The New International Encyclopaedia. Vol. 20. Dodd, Mead.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438129181.

- World Book, Inc (1999). The World Book encyclopedia, Volume 2. World Book, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0716600992.

External links

Media related to North Germanic peoples at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to North Germanic peoples at Wikimedia Commons