Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights Movement was a social movement in the United States that tried to gain equal rights for African Americans that white people had. The movement is famous for using non-violent protests and civil disobedience (peacefully refusing to follow unfair laws). Activists used strategies like boycotts, sit-ins, and protest marches. Sometimes police or racist white people would attack them, but the activists never fought back.

| Civil Rights Movement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Cold War | ||||

Protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963 | ||||

| Date | May 17, 1954 – April 4, 1968 | |||

| Location | ||||

| Caused by | Racism Racial segregation | |||

| Goals | Racial integration | |||

| Methods | Nonviolence Protests Civil disobedience Lawsuits | |||

| Status | Concluded | |||

| Concessions given | Brown v. Board of Education Civil Rights Act of 1964 Voting Rights Act of 1965 Civil Rights Act of 1968 | |||

| Parties to the civil conflict | ||||

| ||||

| Lead figures | ||||

| Units involved | ||||

However, the Civil Rights Movement was made up of many different people and groups. Not everyone believed the same things. For example, the Black Power movement believed black people should demand their civil rights and force white leaders to give them those rights.

The Civil Rights Movement was also made of people of different races and religions. The Movement's leaders and most of its activists were African-American. However, the Movement got political and financial support from labor unions, religious groups, and some white politicians, like Lyndon B. Johnson. Activists of all races came to join African-Americans in marches, sit-ins, and protests.

The Civil Rights Movement was very successful. It helped to get five federal laws and two amendments to the Constitution passed. These officially protected African Americans' rights. It also helped change many white people's attitudes about the way black people were treated and the rights they deserved.

Before the Civil Rights Movement

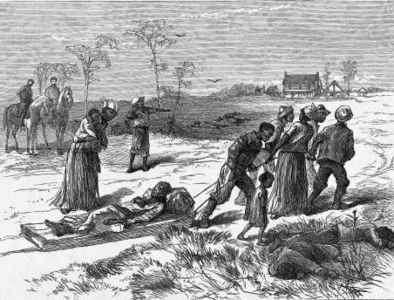

Before the American Civil War, there were almost four million black slaves in the United States. Only white men with property could vote, and only white people could be United States citizens.[1][2][3]

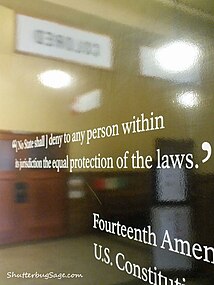

After the Civil War, the United States government passed three Constitutional amendments:[4]

- The 13th Amendment (1865) ended slavery

- The 14th Amendment (1868) gave African Americans citizenship

- The 15th Amendment (1870) gave African American males the right to vote (no women in the U.S. could vote at the time).

In the South

After the Civil War, the U.S. government tried to enforce the rights of ex-slaves in the South through a process called Reconstruction. However, in 1877, Reconstruction ended. By the 1890s, the Southern states' legislatures were all-white again. Southern Democrats, who did not support civil rights for blacks, completely ruled the South.[5] This gave them a lot of power in the United States Congress.[6] For example, Southern Democrats were able to make sure that laws against lynching did not pass.

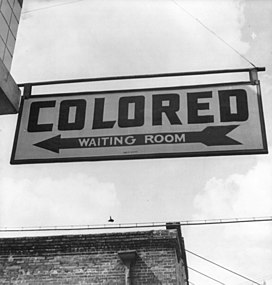

Starting in 1890, Southern Democrats began to pass state laws that took away the rights African Americans had gained. These racist laws became known as Jim Crow laws. For example, they included:

- Laws that made it impossible for blacks to vote (this is called disenfranchisement). Since they could not vote, blacks also could not be on juries.[7][8]

- Laws that required racial segregation - separation of blacks and whites. For example, blacks could not:[6]

- Go to the same schools, restaurants, or hospitals as whites

- Use the same bathrooms as whites or drink from the same water fountains

- Sit in front of whites on buses

In 1896, the United States Supreme Court ruled in a case called Plessy v. Ferguson that these laws were legal. They said that having things be "separate but equal" was fine.[9] In the South, everything was separate. However, places like black schools and libraries got much less money and were not as good as places for whites.[9][10][11] Things were separate, but not equal.

Violence against black people increased. Individuals, groups, police, and huge crowds of people could hurt or even kill African Americans, without the government trying to stop them or punishing them. Lynchings became more common.[11]

Across the United States

Problems were worse in the South. However, social discrimination and tensions affected African Americans in other areas as well.[12]

Segregation in housing was a problem across the United States. Many African Americans could not get mortgages to buy houses. Realtors would not sell black people houses in the suburbs, where white people lived. They also would not rent apartments in white areas.[13] Until the 1950s, the federal government did nothing about this.[13]

When he was elected in 1913, President Woodrow Wilson made government offices segregated. He believed that segregation was best for everyone.[14]

Black people fought in both World War I and World War II. However, the military was segregated, and they were not given the same opportunities as white soldiers. After activism from black veterans, President Harry Truman de-segregated the military in 1948.[15]

Early activism

African Americans tried to fight back against discrimination in many ways. They formed new groups and tried to form labor unions. They tried to use the courts to get justice. For example, in 1909, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was created. It fought to end race discrimination through lawsuits, education, and lobbying.[16]

However, eventually, many African Americans became frustrated and began to dislike the idea of using slow, legal strategies to achieve desegregation. Instead, African American activists decided to use a combination of protests, nonviolence, and civil disobedience. This is how the Civil Rights Movement of 1954-1968 began.

Photo gallery

- 1865 Cartoon about how blacks served in the Civil War and thus should be able to vote

- A white supremacist campaign poster (1866). It tells people to vote for the person who will not support civil rights

- Cartoon from 1904 showing how blacks were not treated equally under "Jim Crow"[18]

- A quote from Woodrow Wilson used in the racist movie Birth of a Nation (1915). The quote says the KKK will save the South from blacks

- A separate movie theater for black people in Mississippi (1937)

- A black man drinks from a "colored" drinking fountain in Oklahoma City (1939)

- Segregation also happened in the North. This sign is from Detroit (1942)

Important events

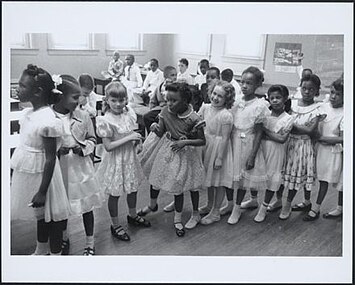

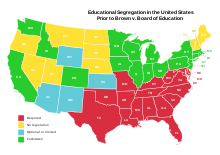

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

Schools in the South, and some other parts of the country, had been segregated since 1896. In that year, the Supreme Court had ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that segregation was legal, as long as things were "separate but equal."

In 1951, thirteen black parents filed a class action lawsuit against the Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas. In the lawsuit, the parents argued that the black and white schools were not "separate but equal." They said the black school was much worse than the white one.[9]

The lawsuit eventually went to the United States Supreme Court. After years of work, Thurgood Marshall and a team of other NAACP lawyers won the case.[9] The Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were illegal.[20] All nine Supreme Court judges agreed.

In their decision, the Court said:

We conclude that, in ... public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. [20]

This was the Civil Rights Movement's first major victory. However, Brown did not reverse Plessy v. Ferguson. Brown made segregation in schools illegal. But segregation in all other places was still legal.

- Members of the NAACP, including Thurgood Marshall (right), won Brown

- The all-white Supreme Court that ruled against school segregation

- Black and white students together after Brown in Washington, D.C.

- U.S. Marshals protect 6-year-old Ruby Bridges, the only black child in a Louisiana school

The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956)

Civil rights leaders focused on Montgomery, Alabama, because the segregation there was so extreme. On December 1, 1955, local black leader Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a public bus to make room for a white passenger. Parks and was a civil rights activist and NAACP member; she had just returned from a training on nonviolent civil disobedience.[21] She was arrested.[22]

African-Americans gathered and organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott. They decided they would not ride on the buses again until they were treated the same as whites. Under segregation, blacks could not sit in front of whites - they had to sit in the back of the bus. Also, if a white person told a black person to move so they could sit down, the black person had to.[23]

Most of Montgomery's 50,000 African Americans took part in the boycott. It lasted for 381 days and almost bankrupt the bus system.[22] Meanwhile, the NAACP had been working on a lawsuit about segregation on buses. In 1956, they won the case, and the Supreme Court ordered Alabama to de-segregate its buses.[24] The boycott ended with a victory.

- The bus Rosa Parks was riding when she refused to give up her seat

De-segregating Little Rock Central High School (1957)

In 1957, the NAACP had signed up nine African American students (called the "Little Rock Nine") to go to Little Rock Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Before this, only whites were allowed at the school. However, the Little Rock School Board had agreed to follow the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education and de-segregate its schools.[25]

Then came the black students' first day of school. The Governor of Arkansas called out soldiers from the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the black students from even entering the school. This was against a Supreme Court ruling, so President Dwight D. Eisenhower got involved. He took control of the Arkansas National Guard and ordered them to leave the school. Then he sent soldiers from the United States Army to protect the students. This was an important civil rights victory. It meant the federal government was willing to get involved and force states to end segregation in schools.[25]

Unfortunately, the Little Rock Nine were treated very badly by many of the white students at the school.[26] At the end of the school year, Little Rock Central High School closed so it would not have to allow black students the next year. Other schools across the South did the same thing.[25]

- White parents rally against integrating Little Rock's schools

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower showed the government would force schools to integrate

- 40th anniversary celebration of de-segregation at Little Rock High, led by President Bill Clinton

Sit-ins (1958-1960)

Between 1958 and 1960, activists used sit-ins to protest segregation at lunch counters (small restaurants inside stores). They would sit at the lunch counter and politely ask to buy some food. When they were told to leave, they would continue to sit quietly at the counter. Often they would stay until the lunch counter closed. Groups of activists would keep coming back to sit in at the same places until those places agreed to serve African Americans at their lunch counters.

In 1958, the NAACP organized the first sit-in in Wichita, Kansas. They sat in at a lunch counter in a store called Dockum's Drug Store. After three weeks, they got the store to de-segregate. Not long after, all of the Dockum Drug Stores in Kansas were de-segregated. Next, students in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma led a successful sit-in at another drug store.

In 1960, college students (including some white students) began to sit in at a Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. After a while, they began to sit in at other lunch counters. In the stores that held these lunch counters, sales dropped by one-third. These stores de-segregated to avoid continuing to lose money. After five months of sit-ins, the Woolworth's in Greensboro also de-segregated its lunch counter. Newspapers all over the country wrote about the Greensboro sit-ins. Soon, people started sitting in across the South.

A few days after the Greensboro students started their sit-in, students in Nashville, Tennessee began their own sit-ins. They chose stores in the part of Nashville that had the most businesses. Before starting their sit-ins, they decided they would not be violent, no matter what. They wrote out rules, which activists in other cities began to use also. Their rules said:

Do not [hit] back or curse if abused. ... Do not block entrances to stores outside [or] the aisles inside. [Be polite] and friendly at all times. Do sit straight; always face the counter. ... Do refer information seekers to your leader in a polite manner. Remember the teachings of Jesus, Gandhi, Martin Luther King. Love and nonviolence is the way.[27]

Many of the Nashville students were attacked and abused by groups of white people; arrested; and even beaten by police. However, the students were always nonviolent. Their protests, and the attacks on them, brought more newspaper stories and attention. It also showed how the activists were truly nonviolent.[28] After three months of sit-ins, all of the lunch counters in Nashville's downtown department stores were de-segregated.[29]

Soon, there were sit-ins all over the country. Sit-ins even happened in Nevada, and in northern states like Ohio. Over 70,000 people, black and white, took part in sit-ins. They used sit-ins to protest all kinds of segregated places - not just lunch counters, but also beaches, parks, museums, libraries, swimming pools, and other public places.[30]

The sit-ins even got the support of President Eisenhower. After the Greensboro sit-ins started, he said he was "deeply sympathetic with the efforts of any group to enjoy the rights of equality that they are guaranteed by the Constitution."[31]

In April 1960, students who had led sit-ins were invited to a conference. At the conference, they decided to form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC would become an important group in the civil rights movement.[32]

- Example of a 1950s lunch counter inside a drug store

- The Woolworth's five and dime store where the Greensboro students sat in

- A sign on a restaurant window in Lancaster, Ohio

Freedom Rides (1961)

In 1960, the Supreme Court had ruled in Boynton v. Virginia that it was illegal to segregate people on public transportation that was going from one state to another. In 1961, student activists decided to test whether the Southern states would follow this ruling. Groups of black and white activists decided to ride buses through the South, sitting together instead of segregating themselves. They planned to ride buses from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans, Louisiana.[33] They called these rides the "Freedom Rides."

The Freedom Riders were met with danger and violence. For example:[34]

- One bus in Alabama was firebombed, and the Freedom Riders had to run for their lives.

- In Birmingham, Alabama, Public Safety Commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor let Ku Klux Klan members attack the Freedom Riders for 15 minutes before the police "protected" them. The Riders were badly beaten, and one needed 50 stitches in his head.

- In Montgomery, Alabama, the Freedom Riders were attacked by a mob (a large, angry group) of white people. This caused a huge riot that lasted two hours. Five Freedom Riders needed to go to the hospital, and 22 others were hurt.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) brought in more Freedom Riders to keep the movement going. They were also met with violence:

| “ | The Negro is different because God made him different to punish him. – Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett, about why he supported segregation[33] | ” |

- In Montgomery, another mob attacked a bus. They knocked one activist unconscious and knocked another's teeth out.[34]

- In Jackson, Mississippi, the Freedom Riders were arrested for using "white only" bathrooms and lunch counters.[33]

- New Freedom Riders joined the movement. As they arrived in Jackson, they were arrested also. By the end of the summer, more than 300 had been put in jail.[33]

A new law

However, people around the country began to support the Freedom Riders, who had never used violence, even when being attacked. Eventually, Robert Kennedy, the Attorney General in his brother John F. Kennedy's government, insisted on a new law about de-segregation. It said that:[35]

- People could sit wherever they chose on buses

- There could be no "white" and "colored" signs in bus stations

- There could be no separate drinking fountains, toilets, or waiting rooms for whites and blacks

- Lunch counters had to serve people of all races

- The Ku Klux Klan were allowed to attack Freedom Riders in Montgomery. Here two children stand with a KKK leader

- Prison camp at the state prison where Freedom Riders were jailed

- Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy insisted on a new law about de-segregation

- Under the new law, segregated buses or bus stations, like this one, were illegal

- John Lewis, now a U.S. Congressman, was attacked during a Freedom Ride

- Sign in Birmingham honoring the Freedom Riders

Voter registration (1961-1965)

Between 1961 and 1965, activist groups worked on trying to get black people registered (signed up) to vote. Since the end of Reconstruction, the Southern states had passed laws and used many strategies to keep black people from registering to vote. Often, these laws did not apply to white people.[7][8]

Voter registration activists started out in Mississippi. All of Mississippi's civil rights organizations joined together to try to get people registered. Activist groups in Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina then started similar programs. However, when the activists tried to register black people to vote, police, white racists, and the Ku Klux Klan beat, arrested, shot, and even murdered them.[36]

Meanwhile, black people who tried to register to vote were fired from their jobs, thrown out of their homes, beaten, arrested, threatened, and sometimes murdered.[36]

In 1964, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. It made discrimination illegal, and specifically said it was illegal to have different voter registration requirements for different races.[37] However, even after this law was passed, the Southern states still made it very difficult for black people to vote. Finally, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed. This law included ways to make sure that all United States citizens were getting their right to vote.[38]

Integrating Mississippi universities (1956–1965)

Starting in 1956, a black man named Clyde Kennard wanted to go to Mississippi Southern College. Kennard had served in the Korean War, and he wanted to use the GI Bill to go to college.[39] The college's president, William McCain, asked state politicians and a local racist group who supported segregation to make sure Kennard never got into the college.[40]

Kenner was arrested twice for crimes he never committed. Eventually he was convicted and sentenced to seven years in prison.[39] After Kennard had spent three years in prison doing forced labor, Governor Ross Barnett pardoned him. Journalists had looked into Kennard's case, and wrote that the state did not give Kennard the treatment he needed for his colon cancer.[39] Kennard died that same year. Later, in 2006, a court ruled that Kennard was innocent of the crimes he had been sent to jail for .[39]

In September 1962, James Meredith won a lawsuit that gave him the right to go to the University of Mississippi.[41] He tried three times to get into the university to sign up for classes. Governor Ross Barnett blocked Meredith each time. He told Meredith: "[N]o school will be integrated in Mississippi while I am your Governor."[42]

Attorney General Robert Kennedy sent United States Marshals to protect Meredith. On September 30, 1962, Meredith was able to enter the college with the Marshals protecting him.[43] However, that evening, students and other racist whites started a riot. They threw rocks and fired guns at the Marshals. Two people were killed; 28 marshals were shot; and another 160 people were hurt.[42] President John F. Kennedy sent the United States Army to the school to stop the riot. Meredith was able to begin classes at the college the day after the Army arrived.[44] Meredith survived harassment and isolation at the college and graduated on August 18, 1963, with a a degree in political science.[45]

Meredith and other activists kept working on de-segregating public universities. In 1965, the first two African American students were able to go to the University of Southern Mississippi.[46]

- Governor Ross Barnett refused to let Meredith into the University

- U.S. Army trucks drive across the University of Mississippi campus on October 3, 1962

- President Kennedy had to send the U.S. Army to stop the riots at the University

- Memorial outside the University's School of Journalism, honoring the journalist who was killed during the riots

Birmingham Campaign (1963)

In 1963, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) started a campaign in Birmingham, Alabama. Its goals were to de-segregate the stores in downtown Birmingham; make hiring fair; and create a committee, including blacks and whites, that would make a plan for de-segregating Birmingham's schools.[47] Martin Luther King described Birmingham as "probably the most [completely] segregated city in the United States."[48]

Birmingham's Commissioner of Public Safety was Eugene "Bull" Connor. (A Commissioner of Public Safety is in charge of the police and fire department, and deals with emergencies that could be dangerous to people in the city.) Connor was very much against integration. He often let the police, Ku Klux Klan, and racist white people attack civil rights activists.[49] He promised that blacks and whites would never be integrated in Birmingham.[50][51]

The activists used a few different non-violent ways of protesting, including sit-ins, "kneel-ins" at local churches, and marches.[52]p. 218 However, the city got a court order saying all protests like this were illegal. The activists knew this was illegal, and in an act of civil disobedience, they refused to follow the court order.[53]p. 108 The protesters, including Martin Luther King, were arrested.[54]

While in jail, King was held in solitary confinement. While there, he wrote his famous "Letter from Birmingham Jail." He was let go after about a week.[53]

The Children's Crusade

However, very few activists could afford to risk being arrested. One of SCLC's leaders then came up with the idea of training high school, college, and elementary school students to take part in the protests.[55] He reasoned that students did not have full-time jobs to go to, they did not have families to take care of, and they could "afford" to be in jail more than their parents.[56]

Newsweek magazine later named this plan the "Children's Crusade."[55] On May 2, more than 600 students, including some as young as 8 years old, tried to march from a local church to City Hall.[57] They were all arrested.[58]

| “ | We're going on in spite of dogs and fire hoses. We've gone too far to turn back. – Martin Luther King, May 3, 1963[50] | ” |

The next day, another 1,000 students started to march. Bull Connor let police dogs loose to attack them and used fire hoses to knock down the students.[59] Reporters were there, and videos and pictures showing the violence were shown on television and printed across the country.[50]

Agreement

People throughout the United States were so angry at seeing these videos that President Kennedy worked with the SCLC and the white businesses in Birmingham to work out an agreement. It said:[52]

- Lunch counters and other public places downtown would be de-segregated

- They would create a committee to figure out how to stop discrimination in hiring

- All jailed protesters would be let go (labor unions like the AFL-CIO had helped raise bail money)

- Black and white leaders would communicate regularly

Some of Birmingham's whites were not happy with this agreement. They bombed the SCLC's headquarters; the home of King's brother; and a hotel where King had been staying. Thousands of blacks reacted by rioting; some burned buildings and one even stabbed and hurt a police officer.[52]p. 301

On September 15, 1963, the Ku Klux Klan bombed a church in Birmingham, where civil rights activists often met before starting their marches. Since it was a Sunday, church services were going on. The bomb killed four young girls and hurt 22 other people.[60]

- Example of what Dr. King's prison cell looked like

- On May 11, a hotel where Dr. King had been staying was bombed

- The church which the Ku Klux Klan bombed in September

- Activists march in Washington, D.C., in memory of the four girls killed in the bombing

"Rising tide of discontent" (1963)

During the spring and summer of 1963, there were protests in over a hundred United States cities, including Northern cities. There were riots in Chicago after a white police officer shot a 14-year-old black boy who was running away from the scene of a robbery.[61] In Philadelphia and Harlem, black activists and white workers fought when the activists tried to integrate state-run construction projects.[62][63] On June 6, over a thousand white people attacked a sit-in in North Carolina; black activists fought back, and a white man was killed.[64]

In Cambridge, Maryland, white leaders declared martial law to stop fighting between blacks and whites. Attorney General Robert Kennedy had to get involved to create an agreement to de-segregate the city.[65]

On June 11, 1963, Alabama Governor George Wallace actually stood in the doorway of the University of Alabama to stop its first two black students from getting inside. President Kennedy had to send United States soldiers to make him get out of the doorway, and make sure that the black students could get into the school.[66]

Meanwhile, the Kennedy government had become very worried. Black leaders had told Robert Kennedy that it was getting harder and harder for African Americans to be nonviolent when they were getting attacked, and when it was taking so long for the United States government to help them get their civil rights.[67] On the evening of June 11, President Kennedy gave a speech about civil rights. He talked about "a rising tide of discontent [unhappiness] that threatens the public safety." He asked Congress to pass new civil rights laws. He also asked Americans to support civil rights as "a moral issue ... in our daily lives."[68]

In the early morning of June 12, Medgar Evers, a leader of the Mississippi NAACP, was murdered by a Ku Klux Klan member.[69]p. 113 The next week, President Kennedy gave Congress his Civil Rights bill, and asked them to make it into law.[69]p. 126

- President John F. Kennedy giving his civil rights speech on June 11, 1963

- Medgar Evers' home, where he was shot while getting out of his car

- The rifle used to murder Evers

- Robert F. Kennedy speaking to civil rights activists in front of the Justice Department on June 14, 1963

- Dr. King with Robert Kennedy after a meeting with civil rights leaders on June 22, 1963

The March on Washington (1963)

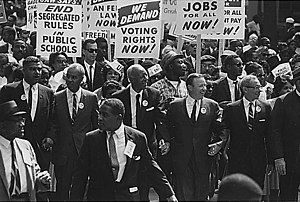

In 1963, civil rights leaders planned a protest march in Washington, D.C. All of the major civil rights groups, some labor unions, and other liberal groups cooperated in planning the march. The march's full name was "The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom." The goals for the march were to get civil rights laws passed; to get the U.S. government to create more jobs; and to get equal, good housing, education, jobs, and voting rights for everyone. However, the most important goal was to get President Kennedy's civil rights law passed.[70]p. 159

Many people thought it would be impossible for so many activists to come together without violence and rioting. The United States government got 19,000 soldiers ready nearby, in case of riots. Hospitals got ready to treat huge numbers of injured people. The government made selling alcohol in Washington, D.C., illegal for the day.[70]p. 159

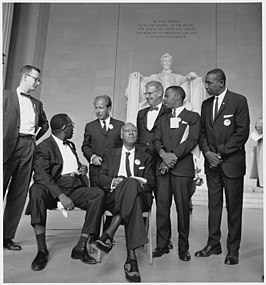

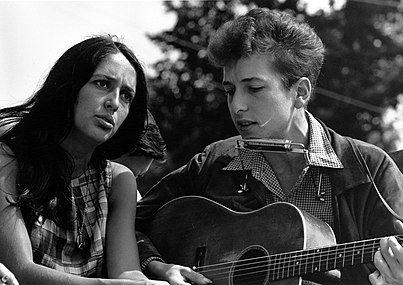

The March on Washington was one of the largest non-violent protests for human rights in United States history.[71] Martin Luther King, Jr., thought that having 100,000 marchers would make the event successful. On August 28, 1963, about 250,000 activists from all over the country came together for the march.[71][72] The marchers included about 60,000 white people (including church groups and labor union members), and between 75 and 100 members of Congress.[70]p. 160 Together, they marched from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial. There, they listened to civil rights leaders speak.

Martin Luther King, Jr., spoke last. His speech, called "I Have a Dream," became one of history's most famous civil rights speeches.[73]

Historians have said that the March on Washington helped get President Kennedy's civil rights bill passed.[74]

- The official program advertising the March on Washington

- The leaders of the March

- Marchers head toward the Lincoln Memorial

- Protestors' signs show how many different kinds of people marched

- Nearly 250,000 people marched, including 60,000 white people

- A protester holds a sign saying "We march together!"

- View of the crowd from the air

- Jackie Robinson and his son at the March

- Four young marchers singing

- Martin Luther King gives his "I Have a Dream" speech

- After the March on Washington, President Kennedy meets with civil rights leaders

Malcolm X joins the movement (1964)

Malcolm X was an American minister who converted to Islam in prison, around 1948. He became a member of the Nation of Islam.[75]p. 138 This group believed in black supremacy - that the black race was the best of all. They believed that blacks should be completely independent from whites, and should eventually return to Africa.[75]pp. 127–128, 132–138[76]pp. 149–152 They also believed that black people had the right to fight back and use violence to get their rights. Because of this, Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam did not support the civil rights movement, because it was non-violent and supported integration.[76]pp. 79–80

However, in March 1964, Malcolm X was kicked out of the Nation of Islam, because he had disagreements with the group's leader, Elijah Muhammad.[77] He offered to work with other civil rights groups, if they accepted that blacks had the right to defend themselves.[78]

On March 26, 1964, Malcolm met with Martin Luther King, Jr. Malcolm had a plan to bring the United States before the United Nations on charges that the U.S. violated African Americans' human rights. Dr. King may have been planning to support this.[79]

Between 1963 and 1964, civil rights activists got more angry and more likely to fight back against whites. In April 1964, Malcolm gave a famous speech called "The Ballot or the Bullet." ("The ballot" means "voting.") In the speech, he said that if the U.S. government is "unwilling or unable to defend the lives and the property of Negroes," then African Americans should defend themselves.[80]p. 43 He warned politicians that many African Americans were not willing "to turn the other cheek any longer."[80]p. 25 Then he warned white America about what would happen if blacks were not allowed to vote:

| “ | [I]f we don't cast a ballot, it's going to end up in a situation where we're going to have to cast a bullet. It's either a ballot or a bullet. ... There's new strategy coming in. It'll be Molotov cocktails this month, hand grenades next month, and something else next month. It'll be ballots, or it'll be bullets. [80]p.30 | ” |

- Malcolm X in 1964

- Elijah Muhammad kicked Malcolm out of the Nation of Islam

Mississippi Freedom Summer (1964)

In the summer of 1964, civil rights groups brought almost 1,000 activists to Mississippi.[81] Most of them were white college students.[82]p. 66 Their goals were to work together with black activists to register voters, and to teach summer school to black children in "Freedom Schools." They also wanted to help create the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). At the time, only white people could take part in the Mississippi Democratic Party. The MFDP was planned as another political party that would allow black and white Democrats to take part in politics.[81]

Many white Mississippians were angry that people from other states were coming in and trying to change their society. Government workers, police, the Ku Klux Klan, and other racist whites used many strategies to attack the activists and black people who were trying to register to vote. The Freedom Summer project lasted for ten weeks. During that time, 1,062 activists were arrested; 80 were beaten; and 4 were killed. Three black Mississippians were murdered because they supported civil rights. Thirty-seven churches, and thirty black homes or businesses, were bombed or burned.[82]

On June 21, 1964, three Freedom Summer activists disappeared. Weeks later, their bodies were found. They had been murdered by members of the local Ku Klux Klan - including some who were also police in the Neshoba County sheriff's department.[81] When people were searching for their bodies in local swamps and rivers, they found the bodies of a 14-year-old boy and seven other men who also seemed to have been murdered at some time.[83]

During Freedom Summer, activists set up at least 30 Freedom Schools, and taught about 3,500 students.[84] The students included children, adults, and the elderly. The schools taught about many things, like black history; civil rights; politics; the freedom movement; and the basic reading and writing skills needed to vote.[85]

Also during the summer, about 17,000 black Mississippians tried to register to vote. Only 1,600 were able to. However, more than 80,000 joined the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). This showed that they wanted to vote and take part in politics, not just let white people do it for them.[86]

- Members of the MFDP at the 1964 Democratic National Convention (DNC)

- Protesters at the DNC hold signs showing the three murdered Freedom Summer activists

- The Ku Klux Klan members who were part of the conspiracy to kill the activists

- Sheriff Lawrence Rainey, who was part of the conspiracy, being taken to court

- Sign honoring the three murdered activists

Civil Rights Act of 1964

John F. Kennedy's suggested civil rights bill[a] had support from Northern members of Congress - both Democrats and Republicans. However, Southern Senators blocked the suggested law from passing. They filibustered for 54 days to block the bill from becoming a law. Finally, President Lyndon B. Johnson got a bill to pass.[88]

On July 2, 1964, Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The law said:[37]

- It was illegal to discriminate against people in public places or jobs, just because of their race, skin color, religion, sex, or home country

- If places broke the law, the Attorney General could file lawsuits against them to force them to follow the law

- Any state or local laws that made it legal to discriminate in public places or jobs were no longer legal

- The proposed law is changed to add protections for women

- President Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act with Dr. King behind him

- Video of Johnson's speech after signing the Civil Rights Act

- Johnson speaks to the media after signing the Act

King awarded Nobel Peace Prize (1964)

In December 1964, Martin Luther King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[89] When giving him the award, the Chairman of the Nobel Committee said:

| “ | Today, now that mankind [has] the atom bomb, the time has come to lay our weapons and armaments aside and listen to the message Martin Luther King has given us[:] "The choice is either nonviolence or nonexistence".... [King] is the first person in the Western world to have shown us that a struggle can be [fought] without violence. He is the first to make the message of brotherly love a reality in the course of his struggle, and he has brought this message to all men, to all nations and races. [89] | ” |

Selma to Montgomery Marches (1965)

In January 1965, Martin Luther King and the SCLC went to Selma, Alabama. Civil rights groups there had asked them to come help get black people registered to vote. At the time, 99% of the people registered to vote in Selma were white.[90] Together, they started working on voting rights.

However, the next month, an African-American man named Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot by a police officer during a peaceful march. Jackson died.[91]pp. 121–123 Many African-American people were very angry. The SCLC was worried that people were so angry that they would get violent.[92]

The SCLC decided to organize a march from Selma to Montgomery.[92] This would be a 54-mile (87-kilometer) march. Activists hoped the march would show how badly African-Americans wanted to vote. They also wanted to show that they would not let racism or violence stop them from getting equal rights.[90]

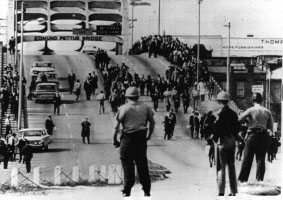

The first march was on March 7, 1965. Police officers and racist whites attacked the marchers with clubs and tear gas. They threatened to throw the marchers off the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Seventeen marchers had to go to the hospital, and 50 others were also injured.[93] This day came to be called Bloody Sunday. Pictures and film of the marchers being beaten were shown in newspapers and on television around the world.[94]

Seeing these things made more people support the civil rights activists. People came from all over the United States to march with the activists. One of them, James Reeb, was attacked by white people for supporting civil rights. He died on March 11, 1965.[95]

Finally, President Johnson decided to send soldiers from the United States Army and the Alabama National Guard to protect the marchers.[91] From March 21 to March 25, the marchers walked along the "Jefferson Davis Highway" from Selma to Montgomery.[91] On March 25, 25,000 people entered Montgomery.[91] Martin Luther King gave a speech called "How Long? Not Long" at the Alabama State Capitol. He told the marchers that it would not be long before they had equal rights, "because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice."[96]

After the march, Viola Liuzzo, a white woman from Detroit, drove some other marchers to the airport. While she was driving back, she was murdered by three members of the Ku Klux Klan.[97]

- Activists marching from Selma to Montgomery

- Police get ready to attack marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge

- Memorial to Viola Liuzzo, who was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan after the march

- The Selma-to-Montgomery march route is now a National Historic Trail

- Video of President Barack Obama's speech on the march's 50th anniversary

- The Obamas, ex-President Bush, and civil rights activists march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge

The Voting Rights Act of 1965

On August 6, 1965, the United States passed the Voting Rights Act. This law made it illegal to stop somebody from voting because of their race. This meant that all the state laws that kept black people from voting were now illegal.[98]

For almost 100 years, registrars (the government workers who had registered people to vote) were all white. They had total power over who they could register and who they would not register. If a registrar refused to let a black person register, that person could only file a lawsuit, which they were not likely to win. However, the Voting Rights Act finally made a change to this system. If a registrar discriminated against black people, the Attorney General could send federal workers to replace local registrars.[98]

The law worked right away. Within a few months, 250,000 new black voters had signed up to vote.[99] One out of every three of them was registered by a federal worker who replaced a racist registrar.[99] In 1965, 74% of Mississippi's black voters actually voted, and more black politicians were elected in Mississippi than in any other state. By 1967, most African Americans were registered to vote in 9 of the 13 states in the South.[99]

Politics in the South were completely changed by African Americans having the power to vote. White politicians could no longer make laws about African Americans without blacks having a say. In many parts of the South, black people outnumbered whites. This meant that they could vote in black politicians, and vote out racist whites. Also, black people who were registered to vote could be on juries. Before this, any time an African American was charged with a crime, the jury that decided whether they were guilty would be all-white.

- Video of Johnson's speech after the Voting Rights Act was passed

- Last page of the Voting Rights Act, with Johnson's signature at the bottom

Fair housing movements (1966-1968)

From 1966 to 1968, the civil rights movement focused a lot on fair housing. Even outside the South, fair housing was a problem. For example, in 1963, California passed a Fair Housing Act which made segregation in housing illegal. White voters and real estate lobbyists got the law reversed the next year. This helped cause the Watts Riots.[100][101] (Later, in 1966, California made the Fair Housing Act the law again.[102])

Activists, including Martin Luther King, led a movement for fair housing in Chicago in 1966. The next year, young NAACP members did the same in Milwaukee. Activists in both cities got attacked physically by white homeowners, and legally by politicians who supported segregation.[103][104]

The Fair Housing Bill

Of all the civil rights laws passed during the Civil Rights Movement, the Fair Housing Act was the hardest to pass.[105] The law would make discrimination in housing illegal. This meant black people would be allowed to move into white neighborhoods. As Senator Walter Mondale said: "This was civil rights getting personal."[106]

The suggested Fair Housing Bill was sent to the United States Senate first. There, most Senators - Northern and Southern - were against the bill. In March of 1968, the Senate sent a weaker version to the House of Representatives. The House was expected to make changes that would make the bill even weaker.[105]

That did not happen. On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was murdered. This made many members of Congress feel like they needed to do something about civil rights quickly.[105] The day after Dr. King's murder, Senator Mondale stood in front of the Senate and said:

| “ | The [biggest supporter] of a nonviolent [relationship] between the races is dead. His generosity to the white man, his belief in the basic good will of all men, and his dramatic, nonviolent action enabled him to speak to both races. . . . We can pray today that the death of the nonviolent leader will not bring violence to life. In the days ahead, we must act to fulfill King's dream. . . . It is up to Congress today to lend powerful support ... by immediately passing the 1968 civil rights bill, and by moving quickly to provide employment and housing opportunities for all blacks and whites. [105] | ” |

On April 10, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968. President Johnson signed the law the next day. Part of the law is called the "Fair Housing Act." It makes it illegal to discriminate in selling, renting, or lending money for housing, based on a person's race, skin color, religion, or home country.

- Failure of California's fair housing law helped cause the Watts Riots

- Senator Walter Mondale spoke in support of the Civil Rights Act of 1968

- President Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1968 into law

The King assassination and the Poor People's Campaign (1968)

In 1968, Martin Luther King and the SCLC were planning the Poor People's Campaign. People of all races took part in the movement. The movement's goal was to decrease poverty for people of all races.[107]

As part of his work against poverty, Dr. King and the SCLC started to speak out against the Vietnam War. King argued that poor people in Vietnam were being killed, and that the War would only make them poorer. He also argued that the United States was spending more and more money and time on the War, and less on programs to help poor Americans.[108]

In March 1968, Dr. King was invited to Memphis, Tennessee to support garbage workers that were on strike. These workers were paid very little, and two workers had been killed doing their jobs. They wanted to be members of a labor union.[109] Dr. King thought this strike was a perfect fit for his Poor People's Campaign.[109] As soon as he got to Memphis, King started getting threats.[110]

The day before he was murdered, King gave a sermon called "I've Been to the Mountaintop."[110] The next day he was murdered. After King was killed, people rioted in more than 100 cities across the United States.[111]

Civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy continued the Poor People's Campaign after King's death. About 3,000 activists camped out on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., for about six weeks.[112]

The day before Dr. King's funeral, his wife, Coretta Scott King, and three of their children led 20,000 marchers through Memphis. Soldiers protected the marchers. On April 9, Mrs. King led another 150,000 people through Atlanta during Dr. King's funeral.[113] An old, wooden wagon, pulled by mules, pulled Dr. King's casket. The wagon was a symbol of Dr. King's Poor People's Campaign.[113]

Mrs. King once said:

| “ | [Martin Luther King, Jr.] gave his life for the poor of the world, the garbage workers of Memphis and the peasants of Vietnam. The day that Negro people and others in bondage are truly free, on the day want is abolished, on the day wars are no more, on that day I know my husband will rest in a long-deserved peace. [114] | ” |

- The motel where King was murdered (now a museum). The wreath marks the spot where King was shot

- Damage to a store from riots in Washington, D.C., after King's murder

- Soliders stand near buildings ruined by riots in Washington, D.C.

- Poor People's Campaign protesters in Washington, D.C.

- "Tent city" where protesters slept in Washington, D.C.

Deaths

Many people were killed during the Civil Rights Movement. Some were killed because they supported civil rights. Others were killed by the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) or other racist whites who wanted to terrorize black people. No one knows just how many people were killed during the Civil Rights Movement.[83] However, here are some examples. People whose names are highlighted in blue were children or teenagers when they were killed.

| Victim(s): | Home: | Year Killed: | Killed In: | Killed By: | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rev. George W. Lee, NAACP member | Mississippi | 1955 | Mississippi | White Citizens' Council members who did not like Rev. Lee registering blacks to vote | [115] |

| Lamar Smith | Mississippi | 1955 | Mississippi | An unknown white man, because Smith had organized blacks to vote | [116] |

| Emmett Till (age 14) | Chicago | 1955 | Mississippi | Lynched by two white men who accused him of flirting with a white woman | [116] |

| John Earl Reese (age 16) | Texas | 1955 | Texas | Shot by white men who were trying to scare blacks into giving up plans for a new school | [116] |

| Willie Edwards | Alabama | 1957 | Alabama | Lynched by four Ku Klux Klan members who thought he was dating a white woman (he wasn't) | [116] |

| Cpl. Roman Ducksworth | 1962 | Mississippi | Police officer who ordered him off a bus and shot him. The officer may have thought he was a Freedom Rider | [116] | |

| Paul Guihard, journalist | England | 1962 | University of Mississippi riots | Students rioting after James Meredith was let into the school | [117] |

| William Lewis Moore | New York | 1963 | Alabama | Killed while on a civil rights march, by himself, from Tennessee to Mississippi | [116] |

| Medgar Evers, NAACP leader | Mississippi | 1963 | The driveway of his home | Byron De La Beckwith (White Citizens' Council member) | [118] |

| Addie Mae Collins (age 14) | Alabama | 1963 | 16th Street Baptist Church bombings | 4 Ku Klux Klan members[b] | [60]p. 147 |

| Denise McNair (11) | Alabama | 1963 | 16th Street Baptist Church bombings | 4 Ku Klux Klan members | [60]p. 147 |

| Carole Robertson (14) | Alabama | 1963 | 16th Street Baptist Church bombings | 4 Ku Klux Klan members | [60]p. 147 |

| Cynthia Wesley (14) | Alabama | 1963 | 16th Street Baptist Church bombings | 4 Ku Klux Klan members | [60]p. 147 |

| Virgil Lamar Ware (13) | Alabama | 1963 | Alabama | Shot by white teenagers who had just come from a rally that supported segregation | [116] |

| Louis Allen | Mississippi | 1964 | Mississippi | Killed after seeing another civil rights worker get murdered | [116] |

| Johnnie May Chappel | Florida | 1964 | Florida | White men looking for a black person to shoot | [116] |

| Rev. Bruce Klunder | Oregon | 1964 | Ohio | Crushed by a bulldozer while protesting a segregated school that was being built | [116] |

| Henry Hezekiah Dee (age 19) | Mississippi | 1964 | Mississippi | Ku Klux Klan members who thought he was part of a plot to get weapons for blacks (he wasn't) | [116] |

| Charles Eddie Moore (19) | Mississippi | 1964 | Mississippi | Ku Klux Klan members who thought he was part of a plot to get weapons for blacks (he wasn't) | [116] |

| James Earl Chaney, Freedom Summer activist | Mississippi | 1964 | Neshoba County, Mississippi | Lynched by 10 KKK members (7 convicted) | [119] |

| Andrew Goodman, Freedom Summer activist | New York City | 1964 | Neshoba County, Mississippi | Lynched by 10 KKK members (7 convicted) | [119] |

| Michael Schwerner, Freedom Summer activist | New York City | 1964 | Neshoba County, Mississippi | Lynched by 10 KKK members (7 convicted) | [119] |

| Lt. Col. Lemuel Penn | Washington, D.C. | 1964 | Georgia | Shot by a Ku Klux Klan member in a passing car while Penn was driving home from U.S. Army Reserve training | [116] |

| Malcolm X | Nebraska | 1965 | New York City | 3 Nation of Islam members[c] | [120] |

| Jimmie Lee Jackson | Alabama | 1965 | Alabama | Police officer during a peaceful march | [91]pp. 121–123 |

| Rev. James Reeb | Boston | 1965 | Selma | 3 white men who beat him for supporting civil rights | [121] |

| Viola Liuzzo | Pennsylvania | 1965 | Selma | 4 Ku Klux Klan members for supporting civil rights [d] | [122] |

| Willie Brewster | Alabama | 1965 | Alabama | Shot by white men who belonged to a violent neo-Nazi group | [116] |

| Jonathan Daniels | Boston | 1965 | Alabama | A deputy sheriff just after being let go from jail. Daniels was jailed for helping with voter registration and protesting | [123] |

| Vernon Dahmer | Mississippi | 1966 | Mississippi | 14 KKK members (4 convicted) who firebombed his house after Dahmer offered to pay poll taxes for blacks who could not afford them, so they could vote | [124] |

| Ben Chester White | Mississippi | 1966 | Mississippi | KKK members who thought they could take attention away from a civil rights march by killing a black man | [116] |

| Wharlest Jackson, NAACP leader | Mississippi | 1967 | Mississippi | KKK members who blew up his car after he got a job that only white people were allowed to have before him | [116] |

| Benjamin Brown | 1967 | Mississippi | Police who fired into a crowd at a student protest Brown was at | [116] | |

| Samuel Ephesians Hammond (age 18) | 1967 | South Carolina State College | Police who fired into a student protest | [116] | |

| Delano Herman Middleton (17) | 1967 | South Carolina State College | Police who fired into a student protest | [116] | |

| Henry Ezekial Smith (19) | 1967 | South Carolina State College | Police who fired into a student protest | [116] | |

| Martin Luther King, Jr. | Georgia | 1968 | Memphis | James Earl Ray | [125] |

An unknown number of other people died or were killed during the Civil Rights Movement.[83]

Related pages

- History: Slavery; American Civil War; Reconstruction; Plessy v. Ferguson

- Causes: Racism; white supremacy; racial segregation; discrimination; Jim Crow laws; lynchings

- People: Martin Luther King, Jr.; Coretta Scott King; James Lawson; James Meredith; Little Rock Nine; Rosa Parks; Malcolm X

- Groups: National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

- Law & government: Law of the United States; case law; federal law; legislation; Constitution of the United States; Supreme Court; United States Congress

- Rights: Civil rights; civil liberties; human rights; right to vote; social equality; social justice

- Other: Ku Klux Klan; sundown towns; White Citizens' Council