A state religion (also called official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not a secular state, is not necessarily a theocracy. State religions are official or government-sanctioned establishments of a religion, but the state does not need to be under the control of the clergy (as in a theocracy), nor is the state-sanctioned religion necessarily under the control of the state.

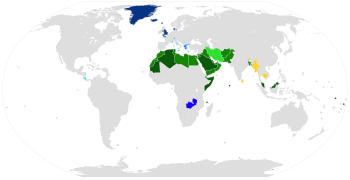

| Christianity (unspecified doctrines) | Islam (unspecified doctrines) |

Official religions have been known throughout human history in almost all types of cultures, reaching into the Ancient Near East and prehistory. The relation of religious cult and the state was discussed by the ancient Latin scholar Marcus Terentius Varro, under the term of theologia civilis (lit. 'civic theology'). The first state-sponsored Christian church was the Armenian Apostolic Church, established in 301 CE.[28] In Christianity, as the term church is typically applied to a place of worship for Christians or organizations incorporating such ones, the term state church is associated with Christianity as sanctioned by the government, historically the state church of the Roman Empire in the last centuries of the Empire's existence, and is sometimes used to denote a specific modern national branch of Christianity. Closely related to state churches are ecclesiae, which are similar but carry a more minor connotation.

In the Middle East, the majority of states with a predominantly Muslim population have Islam as their official religion, though the degree of religious restrictions on citizens' everyday lives varies by country. Rulers of Saudi Arabia use religious power, while Iran's secular presidents are supposed to follow the decisions of religious authorities since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Turkey, which also has Muslim-majority population, became a secular country after Atatürk's Reforms, although unlike the Russian Revolution of the same time period, it did not result in the adoption of state atheism.

The degree to which an official national religion is imposed upon citizens by the state in contemporary society varies considerably; from high as in Saudi Arabia and Iran, to none at all as in Greenland, Denmark, England, Iceland, and Greece (in Europe, the state religion might be called in English, the established church.)

Types

The degree and nature of state backing for denomination or creed designated as a state religion can vary. It can range from mere endorsement (with or without financial support) with freedom for other faiths to practice, to prohibiting any competing religious body from operating and to persecuting the followers of other sects.[29] In Europe, competition between Catholic and Protestant denominations for state sponsorship in the 16th century evolved the principle Cuius regio, eius religio (states follow the religion of the ruler) embodied in the text of the treaty that marked the Peace of Augsburg in 1555. In England, Henry VIII broke with Rome in 1534, being declared the Supreme Head of the Church of England,[b] the official religion of England continued to be "Catholicism without the Pope" until after his death in 1547.[31]

In some cases, an administrative region may sponsor and fund a set of religious denominations; such is the case in Alsace-Moselle in France under its local law, following the pre-1905 French concordatory legal system and patterns in Germany.[32]

State churches

A state church (or "established church") is a state religion established by a state for use exclusively by that state. In the case of a state church, the state has absolute control over the church, but in the case of a state religion, the church is ruled by an exterior body; for example, in the case of Catholicism, the Vatican has control over the church. As of 2024, there are only five state churches left.[33]

Disestablishment

Disestablishment is the process of repealing a church's status as an organ of the state. In a state where an established church is in place, opposition to such a move may be described as antidisestablishmentarianism. This word is, however, most usually associated with the debate on the position of the Anglican churches in the British Isles: the Church of Ireland (disestablished in 1871), the Church in Wales (disestablished in 1920), and the Church of England itself (which remains established in England).[citation needed]

Current states with a state religion

Buddhism

Governments where Buddhism, either a specific form of it, or Buddhism as a whole, has been established as an official religion:

Bhutan: The Constitution defines Buddhism as the "spiritual heritage of Bhutan". The Constitution of Bhutan is based on Buddhist philosophy.[34] It also mandates that the Druk Gyalpo (King) should appoint the Je Khenpo and Dratshang Lhentshog (The Commission for Monastic Affairs).[35]

Bhutan: The Constitution defines Buddhism as the "spiritual heritage of Bhutan". The Constitution of Bhutan is based on Buddhist philosophy.[34] It also mandates that the Druk Gyalpo (King) should appoint the Je Khenpo and Dratshang Lhentshog (The Commission for Monastic Affairs).[35] Cambodia: The Constitution declared Buddhism as the official religion of the country.[36] About 98% of Cambodia's population is Buddhist.[37]

Cambodia: The Constitution declared Buddhism as the official religion of the country.[36] About 98% of Cambodia's population is Buddhist.[37] Myanmar: Section 361 of the Constitution states that "The Union recognizes special position of Buddhism as the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens of the Union."[38] The 1961 State Religion Promotion and Support Act requires : to teach Buddhist lessons in schools, to give priority to Buddhist monasteries in founding of primary schools, to make Uposatha days holidays during Vassa months, to broadcast Buddhist sermons by State media on Uposatha days, and other promotion and supports for Buddhism as State Religion.[39]

Myanmar: Section 361 of the Constitution states that "The Union recognizes special position of Buddhism as the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens of the Union."[38] The 1961 State Religion Promotion and Support Act requires : to teach Buddhist lessons in schools, to give priority to Buddhist monasteries in founding of primary schools, to make Uposatha days holidays during Vassa months, to broadcast Buddhist sermons by State media on Uposatha days, and other promotion and supports for Buddhism as State Religion.[39] Sri Lanka: The constitution of Sri Lanka states under Chapter II, Article 9, "The Republic of Sri Lanka declares Buddhism as the state religion and accordingly it shall be the duty of the Head of State and Head of Government to protect and foster the Buddha Sasana".[40]

Sri Lanka: The constitution of Sri Lanka states under Chapter II, Article 9, "The Republic of Sri Lanka declares Buddhism as the state religion and accordingly it shall be the duty of the Head of State and Head of Government to protect and foster the Buddha Sasana".[40]

In some countries, Buddhism is not recognized as a state religion, but holds special status:

Thailand: Article 67 of the Thai constitution: "The State should support and protect Buddhism". In supporting and protecting Buddhism, the State should promote and support education and dissemination of dharmic principles of Theravada Buddhism, and shall have measures and mechanisms to prevent Buddhism from being undermined in any form. The State should also encourage Buddhists to participate in implementing such measures or mechanisms.[41]

Thailand: Article 67 of the Thai constitution: "The State should support and protect Buddhism". In supporting and protecting Buddhism, the State should promote and support education and dissemination of dharmic principles of Theravada Buddhism, and shall have measures and mechanisms to prevent Buddhism from being undermined in any form. The State should also encourage Buddhists to participate in implementing such measures or mechanisms.[41] Laos: According to the Lao Constitution, Buddhism is given special privilege in the country. The state respects and protects all the lawful activities of Buddhism.[42]

Laos: According to the Lao Constitution, Buddhism is given special privilege in the country. The state respects and protects all the lawful activities of Buddhism.[42] Kalmykia (Russia): The local Government supports Buddhism and also encourages Buddhist teachings and traditions. It also builds various Buddhist temples and sites. Various efforts are taken by the Government for the revival of Buddhism in the republic.[43][44][45]

Kalmykia (Russia): The local Government supports Buddhism and also encourages Buddhist teachings and traditions. It also builds various Buddhist temples and sites. Various efforts are taken by the Government for the revival of Buddhism in the republic.[43][44][45]

Christianity

The following states recognize some form of Christianity as their state or official religion or recognize a special status for it (by denomination):

Non-denominational Christianity

Samoa: In June 2017, Parliament voted to amend the wording of Article 1 of the constitution, thereby making Christianity the state religion. Part 1, Section (1)(3) reads "Samoa is a Christian nation founded on God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit." The status of the religion had previously only been mentioned in the preamble, which Prime Minister Tuilaepa Aiono Sailele Malielegaoi considered legally inadequate.[46][47]

Samoa: In June 2017, Parliament voted to amend the wording of Article 1 of the constitution, thereby making Christianity the state religion. Part 1, Section (1)(3) reads "Samoa is a Christian nation founded on God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit." The status of the religion had previously only been mentioned in the preamble, which Prime Minister Tuilaepa Aiono Sailele Malielegaoi considered legally inadequate.[46][47] Zambia: The preamble to the Zambian Constitution of 1991 declares Zambia to be "a Christian nation", while also guaranteeing freedom of religion.[48]

Zambia: The preamble to the Zambian Constitution of 1991 declares Zambia to be "a Christian nation", while also guaranteeing freedom of religion.[48]

Catholicism

Jurisdictions where Catholicism has been established as a state or official religion:

Costa Rica: Article 75 of the Constitution of Costa Rica confirms that "The Catholic and Apostolic Religion is the religion of the State, which contributes to its maintenance, without preventing the free exercise in the Republic of other forms of worship that are not opposed to universal morality or good customs."[49]

Costa Rica: Article 75 of the Constitution of Costa Rica confirms that "The Catholic and Apostolic Religion is the religion of the State, which contributes to its maintenance, without preventing the free exercise in the Republic of other forms of worship that are not opposed to universal morality or good customs."[49] Holy See: It is an elective, theocratic (or sacerdotal), absolute monarchy ruled by the Pope, who is also the Vicar of Christ.[50] The highest state functionaries are all Catholic clergy of various national origins. It is the sovereign territory of the Holy See (Latin: Sancta Sedes) and the location of the Pope's official residence, referred to as the Apostolic Palace.

Holy See: It is an elective, theocratic (or sacerdotal), absolute monarchy ruled by the Pope, who is also the Vicar of Christ.[50] The highest state functionaries are all Catholic clergy of various national origins. It is the sovereign territory of the Holy See (Latin: Sancta Sedes) and the location of the Pope's official residence, referred to as the Apostolic Palace. Liechtenstein: The Constitution of Liechtenstein describes the Catholic Church as the state religion and enjoying "the full protection of the State". The constitution does however ensure that people of other faiths "shall be entitled to practice their creeds and to hold religious services to the extent consistent with morality and public order".[51]

Liechtenstein: The Constitution of Liechtenstein describes the Catholic Church as the state religion and enjoying "the full protection of the State". The constitution does however ensure that people of other faiths "shall be entitled to practice their creeds and to hold religious services to the extent consistent with morality and public order".[51] Malta: Article 2 of the Constitution of Malta declares that "the religion of Malta is the Catholic and Apostolic Religion".[52]

Malta: Article 2 of the Constitution of Malta declares that "the religion of Malta is the Catholic and Apostolic Religion".[52] Monaco: Article 9 of the Constitution of Monaco describes the "Catholic, and apostolic religion" as the religion of the state.[53]

Monaco: Article 9 of the Constitution of Monaco describes the "Catholic, and apostolic religion" as the religion of the state.[53]

Jurisdictions that give various degrees of recognition in their constitutions to Roman Catholicism without establishing it as the State religion:

Andorra[54]

Andorra[54] Argentina: Article 2 of the Constitution of Argentina explicitly states that the government supports the Roman Catholic Apostolic Faith, but the constitution does not establish a state religion.[55] Before its 1994 amendment, the Constitution stated that the President of the Republic must be a Roman Catholic.

Argentina: Article 2 of the Constitution of Argentina explicitly states that the government supports the Roman Catholic Apostolic Faith, but the constitution does not establish a state religion.[55] Before its 1994 amendment, the Constitution stated that the President of the Republic must be a Roman Catholic. East Timor: While the Constitution of East Timor enshrines the principles of freedom of religion and separation of church and state in Section 45 Comma 1, it also acknowledges "the participation of the Catholic Church in the process of national liberation" in its preamble (although this has no legal value).[56]

East Timor: While the Constitution of East Timor enshrines the principles of freedom of religion and separation of church and state in Section 45 Comma 1, it also acknowledges "the participation of the Catholic Church in the process of national liberation" in its preamble (although this has no legal value).[56] El Salvador: Although Article 3 of the Constitution of El Salvador states that "no restrictions shall be established that are based on differences of nationality, race, sex or religion", Article 26 states that the state recognizes the Catholic Church and gives it legal preference.[57][58]

El Salvador: Although Article 3 of the Constitution of El Salvador states that "no restrictions shall be established that are based on differences of nationality, race, sex or religion", Article 26 states that the state recognizes the Catholic Church and gives it legal preference.[57][58] Guatemala: The Constitution of Guatemala recognises the juridical personality of the Catholic Church. Other churches, cults, entities, and associations of religious character will obtain the recognition of their juridical personality in accordance with the rules of their institution.[59]

Guatemala: The Constitution of Guatemala recognises the juridical personality of the Catholic Church. Other churches, cults, entities, and associations of religious character will obtain the recognition of their juridical personality in accordance with the rules of their institution.[59] Italy: The Constitution of Italy does not establish a state religion, but recognizes the state and the Catholic Church as "independent and sovereign, each within its own sphere".[60] The Constitution additionally reserves to the Catholic faith singular position in regard to the organization of worship, as opposed to all other confessions.[61]

Italy: The Constitution of Italy does not establish a state religion, but recognizes the state and the Catholic Church as "independent and sovereign, each within its own sphere".[60] The Constitution additionally reserves to the Catholic faith singular position in regard to the organization of worship, as opposed to all other confessions.[61] Panama: The Constitution of Panama recognizes Catholicism as "the religion of the majority" of citizens but does not designate it as the official state religion.[62]

Panama: The Constitution of Panama recognizes Catholicism as "the religion of the majority" of citizens but does not designate it as the official state religion.[62] Paraguay: The Constitution of Paraguay recognizes the Catholic Church's role in the nation's historical and cultural formation.[63]

Paraguay: The Constitution of Paraguay recognizes the Catholic Church's role in the nation's historical and cultural formation.[63] Peru: The Constitution of Peru recognizes the Catholic Church as an important element in the historical, cultural, and moral formation of Peru and lends it its cooperation.[64]

Peru: The Constitution of Peru recognizes the Catholic Church as an important element in the historical, cultural, and moral formation of Peru and lends it its cooperation.[64] Poland: The Constitution of Poland states that "The relations between the Republic of Poland and the Roman Catholic Church shall be determined by international treaty concluded with the Holy See, and by statute."[65]

Poland: The Constitution of Poland states that "The relations between the Republic of Poland and the Roman Catholic Church shall be determined by international treaty concluded with the Holy See, and by statute."[65] Spain: The Constitution of Spain of 1978 abolished Catholicism as the official state religion, while recognizing the role it plays in Spanish society.[66]

Spain: The Constitution of Spain of 1978 abolished Catholicism as the official state religion, while recognizing the role it plays in Spanish society.[66]

Eastern Orthodoxy

Greece: The Church of Greece is recognized by the Greek Constitution as the prevailing religion in Greece[67] and is the only country in the world where Eastern Orthodoxy is clearly recognized as a state religion.[68][69] However, this provision does not give exclusivity of worship to the Church of Greece, while all other religions are recognized as equal and may be practiced freely.[70]

Greece: The Church of Greece is recognized by the Greek Constitution as the prevailing religion in Greece[67] and is the only country in the world where Eastern Orthodoxy is clearly recognized as a state religion.[68][69] However, this provision does not give exclusivity of worship to the Church of Greece, while all other religions are recognized as equal and may be practiced freely.[70]

The jurisdictions below give various degrees of recognition in their constitutions to Eastern Orthodoxy, but without establishing it as the state religion:

Bulgaria: In the Bulgarian Constitution, Eastern Orthodoxy is recognized as "the traditional religion" of the Bulgarian people, but the state itself remains secular.[71]

Bulgaria: In the Bulgarian Constitution, Eastern Orthodoxy is recognized as "the traditional religion" of the Bulgarian people, but the state itself remains secular.[71] Cyprus: The Constitution of Cyprus states: "The Autocephalous Greek-Orthodox Church of Cyprus shall continue to have the exclusive right of regulating and administering its own internal affairs and property in accordance with the Holy Canons and its Charter in force for the time being and the Greek Communal Chamber shall not act inconsistently with such right."[72][c]

Cyprus: The Constitution of Cyprus states: "The Autocephalous Greek-Orthodox Church of Cyprus shall continue to have the exclusive right of regulating and administering its own internal affairs and property in accordance with the Holy Canons and its Charter in force for the time being and the Greek Communal Chamber shall not act inconsistently with such right."[72][c] Finland: Both the Finnish Orthodox Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland are "national churches".[73][74]

Finland: Both the Finnish Orthodox Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland are "national churches".[73][74] Georgia: The Georgian Orthodox Church has a constitutional agreement with the state, the constitution recognizing "the special role of the Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia in the history of Georgia and its independence from the state".[75] (See also Concordat of 2002)

Georgia: The Georgian Orthodox Church has a constitutional agreement with the state, the constitution recognizing "the special role of the Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia in the history of Georgia and its independence from the state".[75] (See also Concordat of 2002)

Protestantism

The following states recognize some form of Protestantism as their state or official religion:

The Commonwealth

Anglicanism

The Anglican Church of England is the established church in England as well as all three of the Crown Dependencies:

England: The Church of England is the established church in England, but not in the United Kingdom as a whole.[76] It is the only established Anglican church worldwide. The Anglican Church in Wales, the Scottish Episcopal Church and the Church of Ireland are not established churches and they are independent of the Church of England. The British monarch is the titular Supreme Governor of the Church of England. The 26 most senior bishops in the Church of England are Lords Spiritual and have seats in the House of Lords of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

England: The Church of England is the established church in England, but not in the United Kingdom as a whole.[76] It is the only established Anglican church worldwide. The Anglican Church in Wales, the Scottish Episcopal Church and the Church of Ireland are not established churches and they are independent of the Church of England. The British monarch is the titular Supreme Governor of the Church of England. The 26 most senior bishops in the Church of England are Lords Spiritual and have seats in the House of Lords of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Guernsey: The Church of England is the established church in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, and the leader of the Church of England in the territory is the Dean of Guernsey.[77]

Guernsey: The Church of England is the established church in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, and the leader of the Church of England in the territory is the Dean of Guernsey.[77] Isle of Man: The Church of England is the established church on the Isle of Man. The Bishop of Sodor and Man is an ex officio member of the Legislative Council (the upper house of Tynwald).[78]

Isle of Man: The Church of England is the established church on the Isle of Man. The Bishop of Sodor and Man is an ex officio member of the Legislative Council (the upper house of Tynwald).[78] Jersey: The Church of England is the established church in Jersey, and the leader of the church on the island is the Dean of Jersey, a non-voting member of the States of Jersey.

Jersey: The Church of England is the established church in Jersey, and the leader of the church on the island is the Dean of Jersey, a non-voting member of the States of Jersey.

Calvinism

Scotland: The Church of Scotland is the national church, but not the United Kingdom as a whole.[79] Whilst it is the national church, it 'is not State controlled' and the monarch is not the 'supreme governor' as in the Church of England.[79]

Scotland: The Church of Scotland is the national church, but not the United Kingdom as a whole.[79] Whilst it is the national church, it 'is not State controlled' and the monarch is not the 'supreme governor' as in the Church of England.[79] Tuvalu: The Church of Tuvalu is the state religion, although in practice this merely entitles it to "the privilege of performing special services on major national events".[80] The Constitution of Tuvalu guarantees freedom of religion, including the freedom to practice, the freedom to change religion, the right not to receive religious instruction at school or to attend religious ceremonies at school, and the right not to "take an oath or make an affirmation that is contrary to his religion or belief".[81]

Tuvalu: The Church of Tuvalu is the state religion, although in practice this merely entitles it to "the privilege of performing special services on major national events".[80] The Constitution of Tuvalu guarantees freedom of religion, including the freedom to practice, the freedom to change religion, the right not to receive religious instruction at school or to attend religious ceremonies at school, and the right not to "take an oath or make an affirmation that is contrary to his religion or belief".[81]

Nordic Countries

Lutheranism

Jurisdictions where a Lutheran church has been fully or partially established as a state recognized religion include the Nordic States.

Denmark: Section 4 of the Constitution of Denmark confirms the Church of Denmark as the established church.[82]

Denmark: Section 4 of the Constitution of Denmark confirms the Church of Denmark as the established church.[82] Faroe Islands: The Church of the Faroe Islands is the state church of the Faroe Islands, an autonomous administrative division within the Danish Realm.[83]

Faroe Islands: The Church of the Faroe Islands is the state church of the Faroe Islands, an autonomous administrative division within the Danish Realm.[83] Greenland: The Church of Denmark is the state church of Greenland, an autonomous administrative division within the Danish Realm.[84]

Greenland: The Church of Denmark is the state church of Greenland, an autonomous administrative division within the Danish Realm.[84]

Iceland: The Constitution of Iceland confirms the Church of Iceland as the state church of Iceland.[85]

Iceland: The Constitution of Iceland confirms the Church of Iceland as the state church of Iceland.[85] Norway: Until 2017, the Church of Norway was not a separate legal entity from the government. It was disestablished and became a national church, a legally distinct entity from the state with special constitutional status. The King of Norway is required by the Constitution to be a member of the Church of Norway, and the church is regulated by special canon law, unlike other religions.[86]

Norway: Until 2017, the Church of Norway was not a separate legal entity from the government. It was disestablished and became a national church, a legally distinct entity from the state with special constitutional status. The King of Norway is required by the Constitution to be a member of the Church of Norway, and the church is regulated by special canon law, unlike other religions.[86]

Jurisdictions that give various degrees of recognition in their constitutions to Lutheranism without establishing it as the state religion:

Finland: The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland has a special relationship with the Finnish state, its internal structure being described in a special law, the Church Act.[73] The Church Act can be amended only by a decision of the synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church and subsequent ratification by the Parliament of Finland. The Church Act is protected by the Constitution of Finland and the state cannot change the Church Act without changing the constitution. The church has the power to tax its members. The state collects these taxes for the church, for a fee. On the other hand, the church is required to give a burial place for everyone in its graveyards.[73] The President of Finland also decides the themes for intercession days. The church does not consider itself a state church, as the Finnish state does not have the power to influence its internal workings or its theology, although it has a veto in those changes of the internal structure which require changing the Church Act. Neither does the Finnish state accord any precedence to Lutherans or the Lutheran faith in its own acts.

Finland: The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland has a special relationship with the Finnish state, its internal structure being described in a special law, the Church Act.[73] The Church Act can be amended only by a decision of the synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church and subsequent ratification by the Parliament of Finland. The Church Act is protected by the Constitution of Finland and the state cannot change the Church Act without changing the constitution. The church has the power to tax its members. The state collects these taxes for the church, for a fee. On the other hand, the church is required to give a burial place for everyone in its graveyards.[73] The President of Finland also decides the themes for intercession days. The church does not consider itself a state church, as the Finnish state does not have the power to influence its internal workings or its theology, although it has a veto in those changes of the internal structure which require changing the Church Act. Neither does the Finnish state accord any precedence to Lutherans or the Lutheran faith in its own acts. Sweden: The Church of Sweden was the state church of Sweden between 1527 when King Gustav Vasa broke all ties with Rome and 2000 when the state officially became secular. Much like in Finland, it does have a special relation to the Swedish state unlike any other religious organizations. For example, there is a special law that regulates certain aspects of the church[87] and the members of the royal family are required to belong to it in order to have a claim to the line of succession. A majority of the population still belongs to the Church of Sweden.[88]

Sweden: The Church of Sweden was the state church of Sweden between 1527 when King Gustav Vasa broke all ties with Rome and 2000 when the state officially became secular. Much like in Finland, it does have a special relation to the Swedish state unlike any other religious organizations. For example, there is a special law that regulates certain aspects of the church[87] and the members of the royal family are required to belong to it in order to have a claim to the line of succession. A majority of the population still belongs to the Church of Sweden.[88]

Other/mixed

Armenia: The Armenian Apostolic Church has a constitutional agreement with the State: "The Republic of Armenia shall recognise the exclusive mission of the Armenian Apostolic Holy Church, as a national church, in the spiritual life of the Armenian people, in the development of their national culture and preservation of their national identity."[89]

Armenia: The Armenian Apostolic Church has a constitutional agreement with the State: "The Republic of Armenia shall recognise the exclusive mission of the Armenian Apostolic Holy Church, as a national church, in the spiritual life of the Armenian people, in the development of their national culture and preservation of their national identity."[89] Dominican Republic: The constitution of the Dominican Republic specifies that there is no state church and provides for freedom of religion and belief. A concordat with the Holy See designates Catholicism as the official religion and extends special privileges to the Catholic Church not granted to other religious groups. These include the legal recognition of church law, use of public funds to underwrite some church expenses, and complete exoneration from customs duties.[90]

Dominican Republic: The constitution of the Dominican Republic specifies that there is no state church and provides for freedom of religion and belief. A concordat with the Holy See designates Catholicism as the official religion and extends special privileges to the Catholic Church not granted to other religious groups. These include the legal recognition of church law, use of public funds to underwrite some church expenses, and complete exoneration from customs duties.[90] Haiti: While Catholicism has not been the state religion since 1987, a 19th-century concordat with the Holy See continues to confer preferential treatment to the Catholic Church, in the form of stipends for clergy and financial support to churches and religious schools. The Catholic Church also retains the right to appoint certain amounts of clergy in Haiti without the government's consent.[91][92]

Haiti: While Catholicism has not been the state religion since 1987, a 19th-century concordat with the Holy See continues to confer preferential treatment to the Catholic Church, in the form of stipends for clergy and financial support to churches and religious schools. The Catholic Church also retains the right to appoint certain amounts of clergy in Haiti without the government's consent.[91][92] Hungary: The preamble to the Hungarian Constitution of 2011 describes Hungary as "part of Christian Europe" and acknowledges "the role of Christianity in preserving nationhood", while Article VII provides that "the State shall cooperate with the Churches for community goals." However, the constitution also guarantees freedom of religion and separation of church and state.[93]

Hungary: The preamble to the Hungarian Constitution of 2011 describes Hungary as "part of Christian Europe" and acknowledges "the role of Christianity in preserving nationhood", while Article VII provides that "the State shall cooperate with the Churches for community goals." However, the constitution also guarantees freedom of religion and separation of church and state.[93] Nicaragua: The Nicaraguan Constitution of 1987 states that the country has no official religion, but defines "Christian values" as one of the "principles of the Nicaraguan nation".[94]

Nicaragua: The Nicaraguan Constitution of 1987 states that the country has no official religion, but defines "Christian values" as one of the "principles of the Nicaraguan nation".[94] Portugal: Although Church and State are formally separate, the Catholic Church in Portugal still receives certain privileges.[95]

Portugal: Although Church and State are formally separate, the Catholic Church in Portugal still receives certain privileges.[95]

Islam

Many Muslim-majority countries have constitutionally established Islam, or a specific form of it, as a state religion. Proselytism (converting people away from Islam) is often illegal in such states.[96][97][98][99]

Afghanistan: Officially, Afghanistan has continuously been an Islamic state under various constitutions since at least 1987.[100]

Afghanistan: Officially, Afghanistan has continuously been an Islamic state under various constitutions since at least 1987.[100] Algeria: "Islam shall be the religion of the State."[101][102]

Algeria: "Islam shall be the religion of the State."[101][102] Bangladesh: Article (2A) of the Constitution of Bangladesh declares: "Islam is the state religion of the republic".[103]

Bangladesh: Article (2A) of the Constitution of Bangladesh declares: "Islam is the state religion of the republic".[103] Bahrain: "The religion of the State is Islam."[104][105]

Bahrain: "The religion of the State is Islam."[104][105] Brunei: Article 3 of the Constitution of Brunei: "The official religion of Brunei Darussalam shall be the Islamic Religion ..."[106]

Brunei: Article 3 of the Constitution of Brunei: "The official religion of Brunei Darussalam shall be the Islamic Religion ..."[106] Djibouti: Article 1 of the Constitution of Djibouti: "Islam is the Religion of the State."[107]

Djibouti: Article 1 of the Constitution of Djibouti: "Islam is the Religion of the State."[107] Egypt: Article 2 of the Egyptian Constitution of 2014: "Islam is the religion of the State".[108]

Egypt: Article 2 of the Egyptian Constitution of 2014: "Islam is the religion of the State".[108] Iran: Article 12 of the Constitution of Iran: "The official religion of Iran is Islam and the Twelver Ja'farî school [in usul al-Dîn and fiqh], and this principle will remain eternally immutable."[109] Islam has been Iran's state religion since 1501 dating back to the Safavid dynasty and has continued ever since, excluding the period of breaks in the Pahlavi dynasty.

Iran: Article 12 of the Constitution of Iran: "The official religion of Iran is Islam and the Twelver Ja'farî school [in usul al-Dîn and fiqh], and this principle will remain eternally immutable."[109] Islam has been Iran's state religion since 1501 dating back to the Safavid dynasty and has continued ever since, excluding the period of breaks in the Pahlavi dynasty. Iraq: Article 2 of the Constitution of Iraq: "Islam is the official religion of the State and is a foundation source of legislation ..."[110]

Iraq: Article 2 of the Constitution of Iraq: "Islam is the official religion of the State and is a foundation source of legislation ..."[110] Jordan: Article 2 of the Constitution of Jordan: "Islam is the religion of the State and Arabic is its official language."[111]

Jordan: Article 2 of the Constitution of Jordan: "Islam is the religion of the State and Arabic is its official language."[111] Kuwait: Article 2 of the Constitution of Kuwait: "The religion of the State is Islam and Islamic Law shall be a main source of legislation."[112]

Kuwait: Article 2 of the Constitution of Kuwait: "The religion of the State is Islam and Islamic Law shall be a main source of legislation."[112] Libya: Article 1 of the Libyan interim Constitutional Declaration: "Islam is the Religion of the State and the principal source of legislation is Islamic Jurisprudence (Shari'a)."[113]

Libya: Article 1 of the Libyan interim Constitutional Declaration: "Islam is the Religion of the State and the principal source of legislation is Islamic Jurisprudence (Shari'a)."[113] Malaysia: Article 3 of the Federal Constitution of Malaysia: "Islam is the religion of the Federation; but other religions may be practised in peace and harmony in any part of the Federation."[114]

Malaysia: Article 3 of the Federal Constitution of Malaysia: "Islam is the religion of the Federation; but other religions may be practised in peace and harmony in any part of the Federation."[114] Maldives: Article 10 of the Maldives's Constitution of 2008: "The religion of the State of the Maldives is Islam. Islam shall be the one of the bases of all the laws of the Maldives."[115]

Maldives: Article 10 of the Maldives's Constitution of 2008: "The religion of the State of the Maldives is Islam. Islam shall be the one of the bases of all the laws of the Maldives."[115] Mauritania: Article 5 of the Constitution of Mauritania: "Islam is the religion of the people and of the State."[116]

Mauritania: Article 5 of the Constitution of Mauritania: "Islam is the religion of the people and of the State."[116] Morocco: Article 3 of the Constitution of Morocco: "Islam is the religion of the State, which guarantees to all the free exercise of beliefs [cultes]."[117]

Morocco: Article 3 of the Constitution of Morocco: "Islam is the religion of the State, which guarantees to all the free exercise of beliefs [cultes]."[117] Oman: Article 2 of the Constitution of Oman: "The religion of the State is Islam and Islamic Sharia is the basis for legislation."[118]

Oman: Article 2 of the Constitution of Oman: "The religion of the State is Islam and Islamic Sharia is the basis for legislation."[118] Pakistan: Article 2 of the Constitution of Pakistan: "Islam shall be the State religion of Pakistan."[119]

Pakistan: Article 2 of the Constitution of Pakistan: "Islam shall be the State religion of Pakistan."[119] Palestine: Article 4 of the Basic Law of the State of Palestine: "Islam is the official religion in Palestine. Respect and sanctity of all other heavenly religions shall be maintained."[120]

Palestine: Article 4 of the Basic Law of the State of Palestine: "Islam is the official religion in Palestine. Respect and sanctity of all other heavenly religions shall be maintained."[120] Qatar: Article 1 of the Constitution of Qatar: "Qatar is an independent sovereign Arab State. Its religion is Islam and Shari'a law shall be a main source of its legislations."[121]

Qatar: Article 1 of the Constitution of Qatar: "Qatar is an independent sovereign Arab State. Its religion is Islam and Shari'a law shall be a main source of its legislations."[121] Saudi Arabia: Article 1 of the Basic Law of Saudi Arabia: "The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a sovereign Arab Islamic State. Its religion is Islam."[122]

Saudi Arabia: Article 1 of the Basic Law of Saudi Arabia: "The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a sovereign Arab Islamic State. Its religion is Islam."[122] Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic: Article 2 of the Constitution of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic declares that Islam is the state religion and law origin.[3]

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic: Article 2 of the Constitution of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic declares that Islam is the state religion and law origin.[3] Somalia: Article 2 of the Provisional Constitution of the Federal Republic of Somalia: "Islam is the religion of the State."[123]

Somalia: Article 2 of the Provisional Constitution of the Federal Republic of Somalia: "Islam is the religion of the State."[123] United Arab Emirates: Article 7 of the Constitution of the United Arab Emirates: "Islam shall be the official religion of the Union."[124]

United Arab Emirates: Article 7 of the Constitution of the United Arab Emirates: "Islam shall be the official religion of the Union."[124] Yemen: Article 2 of the Constitution of Yemen: "Islam is the religion of the state, and Arabic is its official language."[125]

Yemen: Article 2 of the Constitution of Yemen: "Islam is the religion of the state, and Arabic is its official language."[125]

In some countries, Islam is not recognized as a state religion, but holds special status:

Tajikistan: Although there is a separation of religion from politics, certain aspects of law also privilege Islam. One such law declares "Islam to be a traditional religion of Tajikistan, with more rights and privileges given to Islamic organizations than to religious groups of non-Muslim origin".[126]

Tajikistan: Although there is a separation of religion from politics, certain aspects of law also privilege Islam. One such law declares "Islam to be a traditional religion of Tajikistan, with more rights and privileges given to Islamic organizations than to religious groups of non-Muslim origin".[126] Tunisia: Article 5 of the Constitution declares that "Tunisia is part of the Muslim world, and the state alone must work to achieve the goals of pure Islam in preserving honourable life of religious freedom". Although, Islam has been given special privileges by the Constitution, though it is no longer the state religion.[127][128]

Tunisia: Article 5 of the Constitution declares that "Tunisia is part of the Muslim world, and the state alone must work to achieve the goals of pure Islam in preserving honourable life of religious freedom". Although, Islam has been given special privileges by the Constitution, though it is no longer the state religion.[127][128] Turkmenistan: The Constitution claims to uphold a secular system in which religious and state institutions are separate. However, in Turkmenistan, the state actively privileges a form of traditional Islam. The culture, including Islam, is a key facet, contributes to the Turkmen national identity. The state encourages the conceptualization of "Turkmen Islam".[129]

Turkmenistan: The Constitution claims to uphold a secular system in which religious and state institutions are separate. However, in Turkmenistan, the state actively privileges a form of traditional Islam. The culture, including Islam, is a key facet, contributes to the Turkmen national identity. The state encourages the conceptualization of "Turkmen Islam".[129] Uzbekistan: Since independence, Islam has taken on an altogether new role in the nation-building process in Uzbekistan. The government affords Islam in special status and declared it as a national heritage and a moral guideline.[130]

Uzbekistan: Since independence, Islam has taken on an altogether new role in the nation-building process in Uzbekistan. The government affords Islam in special status and declared it as a national heritage and a moral guideline.[130]

Judaism

Israel: Although is defined in several of its laws as a "Jewish and democratic state" (medina yehudit ve-demokratit). However, the term "Jewish" is a polyseme that can describe the Jewish people as either an ethnic or a religious group. The debate about the meaning of the term "Jewish" and its legal and social applications is one of the most profound issues with which Israeli society deals. The problem of the status of religion in Israel, even though it is relevant to all religions, usually refers to the status of Judaism in Israeli society. Thus, even though from a constitutional point of view Judaism is not the state religion in Israel, its status nevertheless determines relations between religion and state and the extent to which religion influences the political center.[131] The Law of Return, was passed on 5 July 1950, gives the global diaspora Jews, the right to relocate to Israel and acquire Israeli citizenship. Section - (1) of that law declares that "Every Jew has the right to come to this country as an Oleh, "(Immigrant)". In the Law of Return, the State of Israel gave effect to the Zionist movement's "credo" which called for the establishment of Israel as a Sovereign Jewish state with Democratic setups, ideals and values.[132]

Israel: Although is defined in several of its laws as a "Jewish and democratic state" (medina yehudit ve-demokratit). However, the term "Jewish" is a polyseme that can describe the Jewish people as either an ethnic or a religious group. The debate about the meaning of the term "Jewish" and its legal and social applications is one of the most profound issues with which Israeli society deals. The problem of the status of religion in Israel, even though it is relevant to all religions, usually refers to the status of Judaism in Israeli society. Thus, even though from a constitutional point of view Judaism is not the state religion in Israel, its status nevertheless determines relations between religion and state and the extent to which religion influences the political center.[131] The Law of Return, was passed on 5 July 1950, gives the global diaspora Jews, the right to relocate to Israel and acquire Israeli citizenship. Section - (1) of that law declares that "Every Jew has the right to come to this country as an Oleh, "(Immigrant)". In the Law of Return, the State of Israel gave effect to the Zionist movement's "credo" which called for the establishment of Israel as a Sovereign Jewish state with Democratic setups, ideals and values.[132]

The State of Israel supports religious institutions, particularly Orthodox Jewish ones, and recognizes the "religious communities" as carried over from those recognized under the British Mandate—in turn derived from the pre-1917 Ottoman system of millets. These are Jewish and Christian (Eastern Orthodox, Latin Catholic, Gregorian-Armenian, Armenian-Catholic, Syriac Catholic, Chaldean, Melkite Catholic, Maronite Catholic, and Syriac Orthodox). The fact that the Muslim population was not defined as a religious community does not affect the rights of the Muslim community to practice their faith. At the end of the period covered by the 2009 U.S. International Religious Freedom Report, several of these denominations were pending official government recognition; however, the Government has allowed adherents of not officially recognized groups the freedom to practice. In 1961, legislation gave Muslim Shari'a courts exclusive jurisdiction in matters of personal status. Three additional religious communities have subsequently been recognized by Israeli law: the Druze (prior under Islamic jurisdiction), the Evangelical Episcopal Church, and followers of the Baháʼí Faith.[133]

Political religions

In some countries, there is a political ideology sponsored by the government that may be called political religion.[134]

Multiple religion recognition

China: The government of China officially espouses state atheism,[135] and officially recognizes only five religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Christianity (Catholicism and Protestantism).[136] Despite limitations on certain forms of religious expression and assembly, religion is not banned, and religious freedom is nominally protected under the Chinese constitution. Among the general Chinese population, there are a wide variety of religious practices.[137] The Chinese government's attitude to religion is one of skepticism and non-promotion.[137][138][139][140]

China: The government of China officially espouses state atheism,[135] and officially recognizes only five religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Christianity (Catholicism and Protestantism).[136] Despite limitations on certain forms of religious expression and assembly, religion is not banned, and religious freedom is nominally protected under the Chinese constitution. Among the general Chinese population, there are a wide variety of religious practices.[137] The Chinese government's attitude to religion is one of skepticism and non-promotion.[137][138][139][140] France: The local law in Alsace-Moselle accords official status to four religions in this specific region of France: Judaism, Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism and Calvinism. The law is a remnant of the Napoleonic Concordat of 1801, which was abrogated in the rest of France by the law of 1905 on the separation of church and state. However, at the time, Alsace-Moselle had been annexed by Germany. The Concordat, therefore, remained in force in these areas, and it was not abrogated when France regained control of the region in 1918. Therefore, the separation of church and state, part of the French concept of Laïcité, does not apply in this region.[141]

France: The local law in Alsace-Moselle accords official status to four religions in this specific region of France: Judaism, Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism and Calvinism. The law is a remnant of the Napoleonic Concordat of 1801, which was abrogated in the rest of France by the law of 1905 on the separation of church and state. However, at the time, Alsace-Moselle had been annexed by Germany. The Concordat, therefore, remained in force in these areas, and it was not abrogated when France regained control of the region in 1918. Therefore, the separation of church and state, part of the French concept of Laïcité, does not apply in this region.[141] Indonesia is officially a presidential republic and a unitary state that does not declare or designate a state religion. Officially, the government recognizes six religions: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Confucianism,[142] as well as traditional and indigenous believes.[143] Pancasila comes from the Jakarta Charter whose first article was changed from "Divinity, with the obligation to carry out Islamic law for its adherents" to "the One Divinity", to respect other religions. The Constitution of Indonesia guarantees freedom of religion and the practice of other religions and beliefs, including traditional animistic beliefs. Indonesians who are practicing other unrecognized religions such as Sikhs and Jains are often counted as "Hindu" while Indonesians practicing Orthodoxy are often counted as "Christian" for governmental purposes.[citation needed] Atheism, although not prosecuted, is discouraged by the state ideology of Pancasila. In addition, the province of Aceh receives a special status and a higher degree of autonomy, in which it may enact laws (qanuns) based on the Sharia and enforce it, especially to its Muslim residents.

Indonesia is officially a presidential republic and a unitary state that does not declare or designate a state religion. Officially, the government recognizes six religions: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Confucianism,[142] as well as traditional and indigenous believes.[143] Pancasila comes from the Jakarta Charter whose first article was changed from "Divinity, with the obligation to carry out Islamic law for its adherents" to "the One Divinity", to respect other religions. The Constitution of Indonesia guarantees freedom of religion and the practice of other religions and beliefs, including traditional animistic beliefs. Indonesians who are practicing other unrecognized religions such as Sikhs and Jains are often counted as "Hindu" while Indonesians practicing Orthodoxy are often counted as "Christian" for governmental purposes.[citation needed] Atheism, although not prosecuted, is discouraged by the state ideology of Pancasila. In addition, the province of Aceh receives a special status and a higher degree of autonomy, in which it may enact laws (qanuns) based on the Sharia and enforce it, especially to its Muslim residents. Lebanon: There are 18 officially recognized religious groups in Lebanon, each with its own family law legislation and set of religious courts.[144] Under the terms of an agreement known as the National Pact between the various political and religious leaders of Lebanon, the president of the country must be a Maronite, the Prime Minister must be a Sunni, and the Speaker of Parliament must be a Shia.[145]

Lebanon: There are 18 officially recognized religious groups in Lebanon, each with its own family law legislation and set of religious courts.[144] Under the terms of an agreement known as the National Pact between the various political and religious leaders of Lebanon, the president of the country must be a Maronite, the Prime Minister must be a Sunni, and the Speaker of Parliament must be a Shia.[145] Luxembourg is a secular state, but the Grand Duchy recognizes and supports several denominations, including the Catholic Church, Greek Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, Romanian Orthodox, Serbian Orthodox, Anglican and some Protestantism denominations as well as to Jewish congregations.[146]

Luxembourg is a secular state, but the Grand Duchy recognizes and supports several denominations, including the Catholic Church, Greek Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, Romanian Orthodox, Serbian Orthodox, Anglican and some Protestantism denominations as well as to Jewish congregations.[146] Nepal is a secular nation, and secularism in Nepal under the interim constitution (Part 1, Article 4) is defined as "religious and cultural freedom, along with the protection of religion and culture handed down from time immemorial." That is, "the state government is bound for protecting and fostering Hindu religion" while maintaining "religious" and "cultural" freedom throughout the nation as fundamental rights.

Nepal is a secular nation, and secularism in Nepal under the interim constitution (Part 1, Article 4) is defined as "religious and cultural freedom, along with the protection of religion and culture handed down from time immemorial." That is, "the state government is bound for protecting and fostering Hindu religion" while maintaining "religious" and "cultural" freedom throughout the nation as fundamental rights. Russia: Though a secular state under the constitution, Russia is often said to have Russian Orthodoxy as the de facto national religion, despite other minorities: "The Russian Orthodox Church is de facto privileged religion of the state, claiming the right to decide which other religions or denominations are to be granted the right of registration".[147][148][149][150][151][152][153]

Russia: Though a secular state under the constitution, Russia is often said to have Russian Orthodoxy as the de facto national religion, despite other minorities: "The Russian Orthodox Church is de facto privileged religion of the state, claiming the right to decide which other religions or denominations are to be granted the right of registration".[147][148][149][150][151][152][153]

Islam in Russia is recognized under the law and by Russian political leaders as one of Russia's traditional religions, Islam is a part of Russian historical heritage, and is subsidized by the Russian government.[154] The position of Islam as a major Russian religion, alongside Orthodox Christianity, dates from the time of Catherine the Great, who sponsored Islamic clerics and scholarship through the Orenburg Assembly.[155]

Singapore is officially a secular country and does not have a state religion, and has been named in one study as the "most religiously diverse nation in the world", with no religious group forming a majority.[156] However, the government gives official recognition to ten different religions, namely Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Taoism, Sikhism, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Jainism, and the Baháʼí Faith,[157] and Singapore's penal code explicitly prohibits "wounding religious feelings". The Jehovah's Witnesses and Unification Church are also banned in Singapore, as the government deems them to be a threat to national security.

Singapore is officially a secular country and does not have a state religion, and has been named in one study as the "most religiously diverse nation in the world", with no religious group forming a majority.[156] However, the government gives official recognition to ten different religions, namely Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Taoism, Sikhism, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Jainism, and the Baháʼí Faith,[157] and Singapore's penal code explicitly prohibits "wounding religious feelings". The Jehovah's Witnesses and Unification Church are also banned in Singapore, as the government deems them to be a threat to national security. Switzerland is officially secular at the federal level but 24 of the 26 cantons support both the Swiss Reformed Church and the Roman Catholic Church in various ways.

Switzerland is officially secular at the federal level but 24 of the 26 cantons support both the Swiss Reformed Church and the Roman Catholic Church in various ways. Turkey: The Republic of Turkey is officially a secular country. None of the past and the latest constitutions recognizes an official religion nor promotes any.[158] But; the Directorate of Religious Affairs, an official state institution established by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1924,[159] expresses opinions only on religious matters regarding Sunni institutions.[160] The directorate regulates the operation of the country's hundreds of thousands of registered mosques and employs local and provincial imams (who are civil servants) who are appointed and paid by the state,[161] whilst other sects of Islam with a sizeable minority such as Alevism are not being regulated nor being funded by the directorate.[162]

Turkey: The Republic of Turkey is officially a secular country. None of the past and the latest constitutions recognizes an official religion nor promotes any.[158] But; the Directorate of Religious Affairs, an official state institution established by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1924,[159] expresses opinions only on religious matters regarding Sunni institutions.[160] The directorate regulates the operation of the country's hundreds of thousands of registered mosques and employs local and provincial imams (who are civil servants) who are appointed and paid by the state,[161] whilst other sects of Islam with a sizeable minority such as Alevism are not being regulated nor being funded by the directorate.[162]

In addition, the Treaty of Lausanne explicitly guarantees the security and protection of both Greek and Armenian Orthodox Christian minorities and the Turkish-Jews. Their religious institutions are being recognized officially by the state.[163][164]

Former state religions

Roman religion and Christianity

In Rome, the office of Pontifex Maximus came to be reserved for the Emperor, who was occasionally declared a god posthumously, or sometimes during his reign. Failure to worship the Emperor as a god was at times punishable by death, as the Roman government sought to link emperor worship with loyalty to the Empire. Many Christians and Jews were subject to persecution, torture and death in the Roman Empire because it was against their beliefs to worship the Emperor.[citation needed]

In 311, Emperor Galerius, on his deathbed, declared a religious indulgence to Christians throughout the Roman Empire, focusing on the ending of anti-Christian persecution. Constantine I and Licinius, the two Augusti, by the Edict of Milan of 313, enacted a law allowing religious freedom to everyone within the Roman Empire. Furthermore, the Edict of Milan cited that Christians may openly practice their religion unmolested and unrestricted, and provided that properties taken from Christians be returned to them unconditionally. Although the Edict of Milan allowed religious freedom throughout the Empire, it did not abolish nor disestablish the Roman state cult (Roman polytheistic paganism). The Edict of Milan was written in such a way as to implore the blessings of the deity.[citation needed]

Constantine called up the First Council of Nicaea in 325, although he was not a baptized Christian until years later. Despite enjoying considerable popular support, Christianity was still not the official state religion in Rome, although it was in some neighboring states such as Armenia, Iberia, and Aksum.[citation needed]

Roman religion (Neoplatonic Hellenism) was restored for a time by the Emperor Julian from 361 to 363. Julian does not appear to have reinstated the persecutions of the earlier Roman emperors.[citation needed]

Catholic Christianity, as opposed to Arianism and other ideologies deemed heretical, was declared to be the state religion of the Roman Empire on 27 February 380[169] by the decree De fide catolica of Emperor Theodosius I.[170]

Han dynasty Confucianism

In China, the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) advocated Confucianism as the de facto state religion, establishing tests based on Confucian texts as an entrance requirement into government service—although, in fact, the "Confucianism" advocated by the Han emperors may be more properly termed a sort of Confucian Legalism or "State Confucianism". This sort of Confucianism continued to be regarded by the emperors, with a few notable exceptions, as a form of state religion from this time until the collapse of the Chinese monarchy in 1912. Note, however, there is a debate over whether Confucianism (including Neo-Confucianism) is a religion or purely a philosophical system.[171]

Yuan dynasty Buddhism

During the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China (1271–1368 CE), Tibetan Buddhism was established as the de facto state religion by the Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan dynasty. The top-level department and government agency known as the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs (Xuanzheng Yuan) was set up in Khanbaliq (modern Beijing) to supervise Buddhist monks throughout the empire. Since Kublai Khan only esteemed the Sakya sect of Tibetan Buddhism, other religions became less important. Before the end of the Yuan dynasty, 14 leaders of the Sakya sect had held the post of Imperial Preceptor (Dishi), thereby enjoying special power.[172]

Golden Horde and Ilkhanate

The Mongol rulers Ghazan of Ilkhanate and Uzbeg of Golden Horde converted to Islam in 1295 CE because of the Muslim Mongol emir Nawruz and in 1313 CE because of Sufi Bukharan sayyid and sheikh Ibn Abdul Hamid respectively. Their official favoring of Islam as the state religion coincided with a marked attempt to bring the regime closer to the non-Mongol majority of the regions they ruled. In Ilkhanate, Christian and Jewish subjects lost their equal status with Muslims and again had to pay the poll tax; Buddhists had the starker choice of conversion or expulsion.[173]

Former state churches in British North America

Other states

- The State of Deseret was an unrecognised provisional state of the United States, proposed in 1849, by Mormon settlers in Salt Lake City. The provisional state existed for slightly over two years, but attempts to gain recognition by the United States government floundered for various reasons. The Utah Territory which was then founded was under Mormon control, and repeated attempts to gain statehood met resistance, in part due to concerns that the principle of separation of church and state conflicted with the practice of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints placing their highest value on "following counsel" in virtually all matters relating to their church-centered lives. The state of Utah was eventually admitted to the union on 4 January 1896, after the various issues had been resolved.[174]

Kingdom of Hawaii: From 1862 to 1893 the Church of Hawaii, an Anglican body, was the official state and national church of the Kingdom of Hawaii.[citation needed]

Kingdom of Hawaii: From 1862 to 1893 the Church of Hawaii, an Anglican body, was the official state and national church of the Kingdom of Hawaii.[citation needed] Japanese Empire: see details in the State Shintō article.

Japanese Empire: see details in the State Shintō article. Netherlands: Article 133 of the 1814 Constitution stipulated the Sovereign Prince should be a member of the Reformed Church; this provision was dropped in the 1815 Constitution.[175] The 1815 Constitution also provided for a state salary and pension for the priesthood of established religions at the time (Protestantism, Catholicism and Judaism). This settlement, nicknamed de zilveren koorde (the silver cord), was abolished in 1983.[176][177][178]

Netherlands: Article 133 of the 1814 Constitution stipulated the Sovereign Prince should be a member of the Reformed Church; this provision was dropped in the 1815 Constitution.[175] The 1815 Constitution also provided for a state salary and pension for the priesthood of established religions at the time (Protestantism, Catholicism and Judaism). This settlement, nicknamed de zilveren koorde (the silver cord), was abolished in 1983.[176][177][178] Nepal was the world's only Hindu state until 2015, when the new constitution declared it a secular state. Proselytizing remains illegal.[179][180]

Nepal was the world's only Hindu state until 2015, when the new constitution declared it a secular state. Proselytizing remains illegal.[179][180] Ottoman Empire: the Millet system (Turkish: [millet]; Arabic: مِلَّة) was the independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community (a group abiding by the laws of Muslim Sharia, Christian Canon law, or Jewish Halakha) was allowed to rule itself under its own laws.

Ottoman Empire: the Millet system (Turkish: [millet]; Arabic: مِلَّة) was the independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community (a group abiding by the laws of Muslim Sharia, Christian Canon law, or Jewish Halakha) was allowed to rule itself under its own laws. Spain: Spain formelly is a catholic confesional state under Francisco Franco, currently is a non-confesional state.

Spain: Spain formelly is a catholic confesional state under Francisco Franco, currently is a non-confesional state. Sudan had Islam as the official religion during the rule of Omar al-Bashir according to the Constitution of Sudan of 2005.[181] It was declared a secular state in September 2020.[182]

Sudan had Islam as the official religion during the rule of Omar al-Bashir according to the Constitution of Sudan of 2005.[181] It was declared a secular state in September 2020.[182] Tokugawa shogunate sanctioned Buddhism and Confucianism as the state religions.[183][184] Buddhism became an arm of the shogunate, and temples were used to resident registration. Distinctive schools of Japanese Buddhism such as Zen, Pure Land, and Nichiren structured Japanese religious life until the 19th century.[185] Confucian Zhu Xi's teaching became a major intellectual force, and the Four Books became available to virtually every educated person.[186]

Tokugawa shogunate sanctioned Buddhism and Confucianism as the state religions.[183][184] Buddhism became an arm of the shogunate, and temples were used to resident registration. Distinctive schools of Japanese Buddhism such as Zen, Pure Land, and Nichiren structured Japanese religious life until the 19th century.[185] Confucian Zhu Xi's teaching became a major intellectual force, and the Four Books became available to virtually every educated person.[186]

Established churches and former state churches

Former confessional states

Note: This only includes states that abolished their state religion themselves, not states with a state religion that were conquered, fell apart or otherwise disappeared.

Buddhism

| Country | Denomination | Disestablished |

|---|---|---|

| Laos | Theravada Buddhism | 1975[208] |

| Siam | Theravada Buddhism | 1932 |

| Tokugawa Shogunate | Japanese Buddhism | 1868 |

Hinduism

| Country | Disestablished |

|---|---|

| Nepal | 2008 (de facto)[209] 2015 (de jure)[209] |

Islam

| Country | Denomination | Disestablished |

|---|---|---|

| Sudan | Sunni Islam | 2020[210] |

| Tunisia | Sunni Islam | 2022[127] |

| Turkey | Sunni Islam | 1928[m] |

Shamanism

| Country | Denomination | Disestablished |

|---|---|---|

| Silla | Korean Shamanism | 527 CE |

Shinto

| Country | Denomination | Disestablished |

|---|---|---|

| Japan | State Shinto | 1947 (de facto)[212] |

See also

- Blasphemy law

- Ceremonial deism

- Church tax

- Civil religion

- Confessional state

- Divine rule

- Elite religion

- Institutional theory

- Major religious groups

- Nonsectarian

- Religious education

- Religious law

- Religious toleration

- Secular religion

- Secularism

- Secularity

- Secularization

- Separation of church and state

- Sociology of religion

- State atheism

- Status of religious freedom by country

- Secular state

Notes

References

Further reading

- Rowlands, John Henry Lewis (1989). Church, State, and Society, 1827–1845: the Attitudes of John Keble, Richard Hurrell Froude, and John Henry Newman. Worthing, Eng.: P. Smith [of] Churchman Publishing; Folkestone, Eng.: distr. ... by Bailey Book Distribution. ISBN 1850931321

External links

- McConnell, Michael W. (April 2003). "Establishment and Disestablishment at the Founding, Part I: Establishment of Religion". William and Mary Law Review. 44 (5): 2105. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011.