Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe type of muscular dystrophy predominantly affecting boys.[3][6][7] The onset of muscle weakness typically begins around age four, with rapid progression.[2] Initially, muscle loss occurs in the thighs and pelvis, extending to the arms,[3] which can lead to difficulties in standing up.[3] By the age of 12, most individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophy are unable to walk.[2] Affected muscles may appear larger due to an increase in fat content,[3] and scoliosis is common.[3] Some individuals may experience intellectual disability,[3] and females carrying a single copy of the mutated gene may show mild symptoms.[3]

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Microscopic image of cross-sectional calf muscle from a person with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, showing extensive replacement of muscle fibers by fat cells. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Pediatric neurology, neuromuscular medicine, medical genetics |

| Symptoms | Muscle weakness, trouble standing up, scoliosis[2][3][4] |

| Usual onset | Around age 4[2] |

| Causes | Genetic (X-linked recessive)[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Genetic testing[3] |

| Treatment | Pharmacological treatment, physical therapy, braces, speech therapy, occupational therapy, surgery, assisted ventilation[2][3] |

| Medication | Corticosteroids |

| Prognosis | life expectancy: 28–30 years |

| Frequency | In males, 1 in 3,500-6,000[3] In females, 1 in 50,000,000[5] |

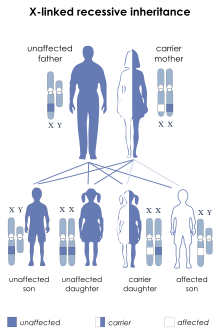

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is caused by mutations and/or deletions in any of the 79 exons encoding the large dystrophin protein, which is essential for maintaining the muscle fiber's cell membrane integrity.[3] The disorder follows an X-linked recessive inheritance pattern, with approximately two-thirds of cases inherited from the mother and one-third resulting from a new mutation.[3] Diagnosis can frequently be made at birth through genetic testing, and elevated creatine kinase levels in the blood are indicative of the condition.[3]

While there is no known cure, management strategies such as physical therapy, braces, and corrective surgery may alleviate symptoms.[2] Assisted ventilation may be required in those with weakness of breathing muscles.[3] Several drugs designed to address the root cause are currently available including gene therapy (Elevidys), and antisense drugs (Ataluren, Eteplirsen etc.).[3] Other medications used include glucocorticoids (Deflazacort, Vamorolone); calcium channel blockers (Diltiazem); to slow skeletal and cardiac muscle degeneration, anticonvulsants to control seizures and some muscle activity, and Histone deacetylase inhibitors (Givinostat) to delay damage to dying muscle cells.[2][3]

Various figures of the occurrence of Duchenne muscular dystrophy are reported. One source reports that it affects about one in 3,500 to 6,000 males at birth.[3] Another source reports Duchenne muscular dystrophy being a rare disease and having an occurrence of 7.1 per 100,000 male births.[8] A number of sources referenced in this article indicate an occurrence of 6 per 100,000.[9]

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the most common type of muscular dystrophy,[3] with a median life expectancy of 28–30 years.[10][11] However, with comprehensive care, some individuals may live into their 30s or 40s.[3] Duchenne muscular dystrophy is considerably rarer in females, occurring in approximately one in 50,000,000 live female births.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Duchenne muscular dystrophy causes progressive muscle weakness due to muscle fiber disarray, death, and replacement with connective tissue or fat.[3] The voluntary muscles are affected first, especially those of the hips, pelvic area, thighs, calves.[3][2][12] It eventually progresses to the shoulders and neck, followed by arms, respiratory muscles, and other areas.[12] Fatigue is common.[13]

Signs usually appear before age five, and may even be observed from the moment a boy takes his first steps.[14] There is general difficulty with motor skills, which can result in an awkward manner of walking, stepping, or running.[15] They tend to walk on their toes,[15] in part due to shortening of the Achilles tendon,[16] and because it compensates for knee extensor weakness.[12] Falls can be frequent.[17] It becomes increasingly difficult for the boy to walk. His ability to walk usually disintegrates completely before age 13.[15] Most men affected with Duchenne muscular dystrophy become essentially "paralyzed from the neck down" by the age of 21.[14] Cardiomyopathy, particularly dilated cardiomyopathy, is common, seen in half of 18-year-olds.[15] The development of congestive heart failure or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) is only occasional.[12] In late stages of the disease, respiratory impairment and swallowing impairment can occur, which can result in pneumonia.[18]

A classic sign of Duchenne muscular dystrophy is trouble getting up from lying or sitting position,[17] as manifested by a positive Gowers's sign. When a child tries to arise from lying on his stomach, he compensates for pelvic muscle weakness through use of the upper extremities:[15] first by rising to stand on his arms and knees, and then "walking" his hands up his legs to stand upright. Another characteristic sign of Duchenne muscular dystrophy is pseudohypertrophy (enlarging) of the muscles of the tongue, calves, buttocks, and shoulders (around age 4 or 5). The muscle tissue is eventually replaced by fat and connective tissue, hence the term pseudohypertrophy. Muscle fiber deformities and muscle contractures of Achilles tendon and hamstrings can occur, which impair functionality because the muscle fibers shorten and fibrose in connective tissue.[12] Skeletal deformities can occur, such as lumbar hyperlordosis, scoliosis, anterior pelvic tilt, and chest deformities. Lumbar hyperlordosis is thought to be compensatory mechanism in response to gluteal and quadriceps muscle weakness, all of which cause altered posture and gait (e.g.: restricted hip extension).[19][20]

Non musculoskeletal manifestations of Duchenne muscular dystrophy occur. There is a higher risk of neurobehavioral disorders (e.g., ADHD), learning disorders (dyslexia), and non-progressive weaknesses in specific cognitive skills (in particular short-term verbal memory),[15] which are believed to be the result of inadequate dystrophin in the brain.[21]

Cause

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is caused by a mutation of the dystrophin gene, located on the short arm of the X chromosome (locus Xp21)[22] that codes for dystrophin protein. Mutations can either be inherited or occur spontaneously during germline transmission,[citation needed] causing a large reduction or absence of dystrophin, a protein that provides structural integrity in muscle cells.[23] Dystrophin is responsible for connecting the actin cytoskeleton of each muscle fiber to the underlying basal lamina (extracellular matrix), through a protein complex containing many subunits. The absence of dystrophin permits excess calcium to penetrate the sarcolemma (the cell membrane).[24]

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is extremely rare in females (about 1 in 50,000,000 female births).[5] It can occur in females with an affected father and a carrier mother, in those who are missing an X chromosome, or those who have an inactivated X chromosome (the most common of the rare reasons).[25] The daughter of a carrier mother and an affected father will be affected or a carrier with equal probability, as she will always inherit the affected X-chromosome from her father and has a 50% chance of also inheriting the affected X-chromosome from her mother.[26]

Disruption of the blood–brain barrier has been seen to be a noted feature in the development of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[27]

Diagnosis

Duchenne muscular dystrophy can be detected with about 95% accuracy by genetic studies performed during pregnancy.[18]

DNA test

The muscle-specific isoform of the dystrophin gene is composed of 79 exons, and DNA testing (blood test) and analysis can usually identify the specific type of mutation of the exon or exons that are affected. DNA testing confirms the diagnosis in most cases.[28]

Muscle biopsy

If DNA testing fails to find the mutation, a muscle biopsy test may be performed.[29] A small sample of muscle tissue is extracted using a biopsy needle. The key tests performed on the biopsy sample for Duchenne muscular dystrophy are immunohistochemistry, immunocytochemistry, and immunoblotting for dystrophin, and should be interpreted by an experienced neuromuscular pathologist.[30] These tests provide information on the presence or absence of the protein. Absence of the protein is a positive test for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Where dystrophin is present, the tests indicate the amount and molecular size of dystrophin, helping to distinguish Duchenne muscular dystrophy from milder dystrophinopathy phenotypes.[31] Over the past several years, DNA tests have been developed that detect more of the many mutations that cause the condition, and muscle biopsy is not required as often to confirm the presence of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[32]

Prenatal tests

A prenatal test can be considered when the mother is a known or suspected carrier.[33]

Prior to invasive testing, determination of the fetal sex is important; while males are sometimes affected by this X-linked disease, female Duchenne muscular dystrophy is extremely rare. This can be achieved by ultrasound scan at 16 weeks or more recently by free fetal DNA (cffDNA) testing. Chorion villus sampling (CVS) can be done at 11–14 weeks, and has a 1% risk of miscarriage. Amniocentesis can be done after 15 weeks, and has a 0.5% risk of miscarriage. Non invasive prenatal testing can be done around 10–12 weeks.[34] Another option in the case of unclear genetic test results is fetal muscle biopsy.[citation needed]

Treatment

No cure for Duchenne muscular dystrophy is known.[35]

Treatment is generally aimed at controlling symptoms to maximize the quality of life which can be measured using specific questionnaires,[36] and include:

- Corticosteroids such as prednisolone, deflazacort and Vamorolone (Agamree) lead to short-term improvements in muscle strength and function up to 2 years.[37] Corticosteroids have also been reported to help prolong walking, though the evidence for this is not robust.[38]

- Disease-specific physical therapy is helpful to maintain muscle strength, flexibility, and function. It aims to:[39]

- Minimize the development of contractures and deformity by developing a programme of stretches and exercises where appropriate

- Anticipate and minimize other secondary complications of a physical nature by recommending bracing and durable medical equipment[40]

- Monitor respiratory function and advise on techniques to assist with breathing exercises and methods of clearing secretions[39]

- Orthopedic appliances (such as braces and wheelchairs) may improve mobility and the ability for self-care. Form-fitting removable leg braces that hold the ankle in place during sleep can defer the onset of contractures.

- Appropriate respiratory support as the disease progresses is important.

- Cardiac problems may require a pacemaker.[41]

The medication eteplirsen, a Morpholino antisense oligo, has been approved in the United States for the treatment of mutations amenable to dystrophin exon 51 skipping. The US approval has been controversial[42] as eteplirsen failed to establish a clinical benefit;[43] it has been refused approval by the European Medicines Agency.[44][45]

The medication ataluren (Translarna) is approved for use in the European Union.[46][47]

The antisense oligonucleotide golodirsen (Vyondys 53) was approved for medical use in the United States in 2019, for the treatment of cases that can benefit from skipping exon 53 of the dystrophin transcript.[48][49]

The Morpholino antisense oligonucleotide viltolarsen (Viltepso) was approved for medical use in the United States in August 2020, for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) in people who have a confirmed mutation of the DMD gene that is amenable to exon 53 skipping.[50] It is the second approved targeted treatment for people with this type of mutation in the United States.[50] Approximately 8% of people with DMD have a mutation that is amenable to exon 53 skipping.[50]

Casimersen (Amondys 45) was approved for medical use in the United States in February 2021,[51] and it is the first FDA-approved targeted treatment for people who have a confirmed mutation of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene that is amenable to exon 45 skipping.[51]

Comprehensive multidisciplinary care guidelines for Duchenne muscular dystrophy have been developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and were published in 2010.[29] An update was published in 2018.[52][53]

Delandistrogene moxeparvovec (Elevidys) is a gene therapy that in June 2023 received United States FDA accelerated approval for treatment of four and five-year-old children.[54][55]

In March 2024, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted approval for givinostat (Duvyzat), an oral medication, to be used in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in people aged six years and older. Givinostat is the first nonsteroidal drug to receive FDA approval for the treatment of all genetic variants of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Functioning as a histone deacetylase (Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, givinostat operates by targeting pathogenic processes within the body, ultimately leading to a reduction in inflammation and muscle loss associated with the disease.[56]

Prognosis

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a rare progressive disease which eventually affects all voluntary muscles and involves the heart and breathing muscles in later stages. Life expectancy is estimated to be around 25–26,[18][57] but this varies. People born with Duchenne muscular dystrophy after 1990 have a median life expectancy of approximately 28–30.[11][10] With excellent medical care, affected men often live into their 30s.[58] David Hatch of Paris, Maine, may have been the oldest person in the world with the disease; he lived to the age of 56.[59][60]

The most common direct cause of death in people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy is respiratory failure. Complications from treatment, such as mechanical ventilation and tracheotomy procedures, are also a concern. The next leading cause of death is cardiac-related conditions such as heart failure brought on by dilated cardiomyopathy. With respiratory assistance, the median survival age can reach up to 40. In rare cases, people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy have been seen to survive into their forties or early fifties, with proper positioning in wheelchairs and beds, and the use of ventilator support (via tracheostomy or mouthpiece), airway clearance, and heart medications.[61] Early planning of the required supports for later-life care has shown greater longevity for people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[62]

Curiously, in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the lack of dystrophin is associated with increased calcium levels and skeletal muscle myonecrosis. The intrinsic laryngeal muscles (ILMs) are protected and do not undergo myonecrosis.[63] ILMs have a calcium regulation system profile suggestive of a better ability to handle calcium changes in comparison to other muscles, and this may provide a mechanistic insight for their unique pathophysiological properties.[64] In addition, patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy also have elevated plasma lipoprotein levels, implying a primary state of dyslipidemia in patients.[65]

Epidemiology

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the most common type of muscular dystrophy; it affects about one in 5,000 males at birth.[3] Duchenne muscular dystrophy has an incidence of one in 3,600 male infants.[18]

In the US, a 2010 study showed a higher amount of those with Duchenne muscular dystrophy age ranging from 5 to 54 who are Hispanic compared to non-Hispanic Whites, and non-Hispanic Blacks.[66][67]

History

The disease was first described by the Neapolitan physician Giovanni Semmola in 1834 and Gaetano Conte in 1836.[68][69][70] However, Duchenne muscular dystrophy is named after the French neurologist Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne (1806–1875), who in the 1861 edition of his book Paraplégie hypertrophique de l'enfance de cause cérébrale, described and detailed the case of a boy who had this condition. A year later, he presented photos of his patient in his Album de photographies pathologiques. In 1868, he gave an account of 13 other affected children. Duchenne was the first to do a biopsy to obtain tissue from a living patient for microscopic examination.[71][72]

Society and culture

Notable cases

- Alfredo Ferrari was an Italian automotive engineer, the eldest son of automaker Enzo Ferrari, and the planned heir to his father's sports car company, Ferrari. Alfredo died of DMD on 30 June 1956 at the age of 24.[73][74]

- Rapper and disability rights advocate Darius Weems had the disease and used his notoriety to raise awareness and funds for treatment, as seen in the documentary Darius Goes West (2007).[75] He died at the age of 27 in 2016.[76]

- Jonathan Evison's novel, The Revised Fundamentals of Caregiving, published in 2012, depicted a young man affected by the disease. In 2016, Netflix released The Fundamentals of Caring, a film based on the novel.[77]

Research

Efforts are ongoing to find medications that either return the ability to make dystrophin or utrophin.[78] Other efforts include trying to block the entry of calcium ions into muscle cells.[79]

Exon-skipping

Antisense oligonucleotides (oligos), structural analogs of DNA, are the basis of a potential treatment for 10% of people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[80] The compounds allow faulty parts of the dystrophin gene to be skipped when it is transcribed to RNA for protein production, permitting a still-truncated but more functional version of the protein to be produced.[81] It is also known as nonsense suppression therapy.[82]

Two kinds of antisense oligos, 2'-O-methyl phosphorothioate oligos (like Drisapersen) and Morpholino oligos (like eteplirsen), have tentative evidence of benefit and are being studied.[83] Eteplirsen is targeted to skip exon 51.[83] "As an example, skipping exon 51 restores the reading frame of ~ 15% of all the boys with deletions. It has been suggested that by having 10 AONs to skip 10 different exons it would be possible to deal with more than 70% of all DMD boys with deletions."[80] This represents about 1.5% of cases.[80]

People with Becker's muscular dystrophy, which is milder than DMD, have a form of dystrophin which is functional even though it is shorter than normal dystrophin.[84] In 1990 England et al. noticed that a patient with mild Becker muscular dystrophy was lacking 46% of his coding region for dystrophin.[84] This functional, yet truncated, form of dystrophin gave rise to the notion that shorter dystrophin can still be therapeutically beneficial. Concurrently, Kole et al. had modified splicing by targeting pre-mRNA with antisense oligonucleotides (AONs).[85] Kole demonstrated success using splice-targeted AONs to correct missplicing in cells removed from beta-thalassemia patients[86][87] Wilton's group tested exon skipping for muscular dystrophy.[88][89]

Gene therapy

Researchers are working on a gene editing method to correct a mutation that leads to Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).[90] Researchers used a technique called CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing, which can precisely remove a mutation in the dystrophin gene in DNA, allowing the body's DNA repair mechanisms to replace it with a normal copy of the gene.[91][92]

Genome editing through the CRISPR/Cas9 system is not currently feasible in humans. However, it may be possible, through advancements in technology, to use this technique to develop therapies for DMD in the future.[93][94] In 2007, researchers did the world's first clinical (viral-mediated) gene therapy trial for Duchenne MD.[95]

Biostrophin is a delivery vector for gene therapy in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and Becker muscular dystrophy.[96]

Future developments

Several medications designed to address the root cause are under development, including gene therapy and antisense drugs.[3] Other medications used include corticosteroids to slow muscle degeneration.[2] Physical therapy, orthopedic braces, and corrective surgery may help with some symptoms[2] while assisted ventilation may be required in those with weakness of breathing muscles.[3] Outcomes depend on the specific type of disorder.[97][3]

References

External links