利用者:野島崎沖/作業場4号室

アンシャン・レジーム(Ancien Régime)はフランス語で「旧支配」、「旧王国」または「旧体制」を意味し、主にヴァロワ朝後期からブルボン朝時代の15世紀から18世紀のフランス社会政治体制、貴族制のことを表す。アンシャン・レジームの社会行政機構は数世紀に及ぶ国政運営とヴィレールコトレ布告などの諸法令、戦争そして内戦の結果形成されたものであるが、これらは依然として地域的諸特権や歴史的相違の混乱した寄せ集めであり続けた。

中世フランスにおける中央集権化のほんとんどは百年戦争によって失われてしまい、ヴァロワ朝による分断された中央権力を再建する試みはユグノー戦争によって妨げられている。ブルボン朝のアンリ4世、ルイ13世そしてルイ14世初期の治世は行政の中央集権化に傾注している。「絶対王政」の概念(その典型が国王によって発せられる拘禁令状(Lettre de cachet)である)と国王による中央集権化の努力に関わらず、アンシャン・レジーム期のフランスは制度的不規則が残る国家だった。税制を含む行政、立法、司法そして教区と特権はしばしば互いに重なり合い、一方、フランス貴族たちは地方の行政や司法事項における自己の権利を保持しようと闘争し、フロンドの乱のような大規模な内戦が中央集権化に抵抗していた。

この時代の中央集権の必要は王家の財政難と戦争が直接関係している。16世紀と17世紀の国内紛争と王家の危機(ユグノー戦争とハプスブルク家との紛争)そして17世紀のフランス領土拡大は莫大な出費を要し、これらはタイユ税(国王直接税)や塩税などの諸税の徴収と貴族からの奉仕によって賄われていた。

この中央集権化の要点は国王と他の貴族を組織化していた個人的なクリアンテール(clientele:パトロン)システムを国家による制度化したシステムに取り換えた事であった[1] 。各地方に対して王権を代表する地方監督官(Intendant)の創設は地方貴族の権力を大きく低下させた。司法官及び国王顧問としての法服貴族(noblesse de robe)に宮廷が大きく依存していたことも同様であった。地方高等法院の設置は当初は新たに併合した土地へ王権の導入を促す目的があったが、高等法院が自信を持つとともに、彼ら自体が統一を妨げる根源となってしまった。

県と行政区画

領土の拡大

In the mid 15th century, France was significantly smaller than it is today,[2] and numerous border provinces (such as en:Roussillon, en:Cerdagne, en:Calais, en:Béarn, Navarre, en:County of Foix, Flanders, en:Artois, Lorraine, en:Alsace, Trois-Évêchés, en:Franche-Comté, en:Savoy, en:Bresse, en:Bugey, Gex, en:Nice, en:Provence, en:Dauphiné, and en:Brittany) were either autonomous or belonged to the en:Holy Roman Empire or en:Spain; there were also foreign enclaves, like the en:Comtat Venaissin. In addition, certain provinces within France were ostensibly personal fiefdoms of noble families (like the en:Bourbonnais, Marche, en:Forez and Auvergne provinces held by the en:House of Bourbon until the provinces were forcibly integrated into the royal domain in 1527 after the fall of en:Charles III, Duke of Bourbon).

The late 15th, 16th and 17th centuries would see France undergo a massive territorial expansion and an attempt to better integrate its provinces into an administrative whole.

French acquisitions from 1461-1789:

- under Louis XI - en:Provence (1482), en:Dauphiné (1461, under French control since 1349)

- under François I - en:Brittany (1532)

- under Henri II - en:Calais, Trois-Évêchés (1552)

- under Henri IV - en:County of Foix (1607)

- under Louis XIII - en:Béarn and Navarre (1620, under French control since 1589 as part of Henri IV's possessions)

- under Louis XIV

- en:Treaty of Westphalia (1648) - en:Alsace

- en:Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) - en:Artois, en:Northern Catalonia (en:Roussillon, en:Cerdagne)

- en:Treaty of Nijmegen (1678-9) - en:Franche-Comté, Flanders

- under Louis XV - Lorraine (1766), en:Corsica (1768)

地方行政

Despite efforts by the kings to create a centralized state out of these provinces, France in this period remained a patchwork of local privileges and historical differences, and the arbitrary power of the monarch (as implied by the expression "absolute monarchy") was in fact much limited by historic and regional particularities. Administrative (including taxation), legal (en:parlement), judicial, and ecclesiastic divisions and prerogatives frequently overlapped (for example, French bishoprics and dioceses rarely coincided with administrative divisions). Certain provinces and cities had won special privileges (such as lower rates in the en:gabelle or salt tax). The en:south of France was governed by written law adapted from the Roman legal system, the north of France by en:common law (in 1453 these common laws were codified into a written form).

The representative of the king in his provinces and cities was the "gouverneur". Royal officers chosen from the highest nobility, provincial and city governors (oversight of provinces and cities was frequently combined) were predominantly military positions in charge of defense and policing. Provincial governors — also called "lieutenants généraux" — also had the ability of convoking provincial parlements, provincial estates and municipal bodies. The title "gouverneur" first appeared under Charles VI. The ordinance of Blois of 1579 reduced their number to 12, but an ordinance of 1779 increased their number to 39 (18 first-class governors, 21 second-class governors). Although in principle they were the king's representatives and their charges could be revoked at the king's will, some governors had installed themselves and their heirs as a provincial dynasty. The governors were at the height of their power from the middle of the 16th to the mid-17th century, but their role in provincial unrest during the civil wars led en:Cardinal Richelieu to create the more tractable positions of en:intendants of finance, policing and justice, and in the 18th century the role of provincial governors was greatly curtailed.

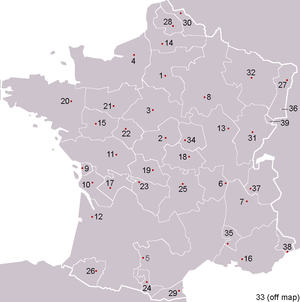

In an attempt to reform the system, new divisions were created. The recettes générales, commonly known as "en:généralités", were initially only taxation districts (see State finances below). The first sixteen were created in en:1542 by edict of Henry II. Their role steadily increased and by the mid 17th century, the généralités were under the authority of a "en:intendant", and they became a vehicle for the expansion of royal power in matters of justice, taxation and policing. By the Revolution, there were 36 généralités; the last two were created in en:1784.

| Généralités of France by city (and province). Areas in red are "pays d'état" (note: should also include 36, 37 and parts of 35); white "pays d'élection"; yellow "pays d'imposition" (see State finances below). | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|  |

財政

The desire for more efficient tax collection was one of the major causes for French administrative and royal centralization in the early modern period. The en:taille became a major source of royal income. Exempted from the taille were clergy and nobles (except for non-noble lands they held in "pays d'état", see below), officers of the crown, military personnel, magistrates, university professors and students, and certain cities ("villes franches") such as Paris.

The provinces were of three sorts, the "pays d'élection", the "pays d'état" and the "pays d'imposition". In the "pays d'élection" (the longest held possessions of the French crown; some of these provinces had had the equivalent autonomy of a "pays d'état" in an earlier period, but had lost it through the effects of royal reforms) the assessment and collection of taxes were trusted to elected officials (at least originally, later these positions were bought), and the tax was generally "personal", meaning it was attached to non-noble individuals. In the "pays d'état" ("provinces with provincial estates"), en:Brittany, en:Languedoc, Burgundy, Auvergne, en:Béarn, en:Dauphiné, en:Provence and portions of en:Gascony, such as en:Bigorre, en:Comminges and the en:Quatre-Vallées, recently acquired provinces which had been able to maintain a certain local autonomy in terms of taxation, the assessment of the tax was established by local councils and the tax was generally "real", meaning that it was attached to non-noble lands (meaning that nobles possessing such lands were required to pay taxes on them). "Pays d'imposition" were recently conquered lands which had their own local historical institutions (they were similar to the "pays d'état" under which they are sometimes grouped), although taxation was overseen by the royal en:intendant.

Taxation districts had gone through a variety of mutations from the 14th century on. Before the 14th century, oversight of the collection of royal taxes fell generally to the en:baillis and sénéchaux in their circumscriptions. Reforms in the 14th and 15th centuries saw France's royal financial administration run by two financial boards which worked in a collegial manner: the four Généraux des finances (also called "général conseiller" or "receveur général" ) oversaw the collection of taxes (en:taille, aides, etc.) by tax-collecting agents (receveurs) and the four Trésoriers de France (Treasurers) oversaw revenues from royal lands (the "domaine royal"). Together they were often referred to as "Messieurs des finances". The four members of each board were divided by geographical circumscriptions (although the term "généralité" isn't found before the end of the 15th century); the areas were named Languedoïl, Languedoc, Outre-Seine-and-Yonne, and Nomandy (the latter was created in 1449; the other three were created earlier), with the directors of the "Languedoïl" region typically having an honorific preeminence. By 1484, the number of généralités had increased to 6.

In the 16th century, the kings of France, in an effort to exert more direct control over royal finances and to circumvent the double-board (accused of poor oversight) -- instituted numerous administrative reforms, including the restructuring of the financial administration and an increase in the number of "généralités". In en:1542, Henry II, France was divided into 16 "généralités". The number would increase to 21 at the end of the 16th century, and to 36 at the time of the French Revolution; the last two were created in en:1784.

The administration of the généralités of the Renaissance went through a variety of reforms. In 1577, Henri III established 5 treasurers ("trésoriers généraux") in each généralité who would form a bureau of finances. In the 17th century, oversight of the généralités was subsumed by the en:intendants of finance, justice and police, and the expression "généralité and "intendance" became roughly synonymous.

Until the late 17th century, tax collectors were called receveurs. In 1680, the system of the en:Ferme Générale was established, a franchised customs and excise operation in which individuals bought the right to collect the taille on behalf of the king, through 6-years adjudications (certain taxes like the aides and the gabelle had been farmed out in this way as early as 1604). The major tax collectors in that system were known as the fermiers généraux (farmers-general in English).

The taille was only one of a number of taxes. There also existed the "taillon" (a tax for military purposes), a national salt tax (the en:gabelle), national tarifs (the "aides") on various products (wine, beer, oil, and other goods), local tarifs on speciality products (the "douane") or levied on products entering the city (the "octroi") or sold at fairs, and local taxes. Finally, the church benefited from a mandatory tax or en:tithe called the "dîme".

en:Louis XIV of France created several additional tax systems, including the "capitation" (begun in 1695) which touched every person including nobles and the clergy (although exemption could be bought for a large one-time sum) and the "dixième" (1710-1717, restarted in 1733), enacted to support the military, which was a true tax on income and on property value. In 1749, under en:Louis XV of France, a new tax based on the "dixième", the "vingtième" (or "one-twentieth"), was enacted to reduce the royal deficit, and this tax continued through the remaining years of the ancien régime.

Another key source of state financing was through charging fees for state positions (such as most members of parlements, magistrates, en:maître des requêtes and financial officers). Many of these fees were quite elevated, but some of these offices conferred nobility and could be financially advantageous. The use of offices to seek profit had become standard practice as early as the 12th and 13th centuries. A law in 1467 made these offices unrevocable, except through the death, resignation or forfeiture of the title holder, and these offices, once bought, tended to become hereditary charges (with a fee for transfer of title) passed on within families. In an effort to increase revenues, the state often turned to the creation of new offices. Before it was made illegal in 1521, It had been possible to leave open-ended the date that the transfer of title was to take effect. In 1534, the "forty days rule" was instituted (adapted from church practice), which made the successor's right void if the preceding office holder died within forty days of the transfer and the office returned to the state;however, a new fee, called the survivance jouissante protected against the forty days rule.[3] In 1604, Sully created a new tax, the "en:paulette" or "annual tax" (1/60 of the amount of the official charge), which permitted the title-holder to be free of the 40 day rule. The "paulette" and the venality of offices would become key concerns in the parlementarian revolts of the 1640s (en:La Fronde).

The state also demanded of the church a "free gift", which the church collected from holders of eccleciastic offices through taxes called the "décime" (roughly 1/20th of the official charge, created under François I).

State finances also relied heavily on borrowing, both private (from the great banking families in Europe) and public. The most important public source for borrowing was through the system of rentes sur l'Hôtel de Ville of Paris, a kind of government bond system offering investers annual interest. This system first came to use in 1523 under François I.

Until 1661, the head of the financial system in France was generally the en:surintendant des finances; with the fall of en:Fouquet, this was replaced by the lesser position of en:contrôleur général des finances.

For more information on the Ancien Régime economy, see en:Economic history of France.

司法

下級裁判所

Justice in seigneurial lands (including those held by the church or within cities) was generally overseen by the seigneur or his delegated officers. Since the 15th century, much of the seigneur's legal purview had been given to the bailliages or sénéchaussées and the présidiaux (see below), leaving only affairs concerning seigeurial dues and duties, and small affairs of local justice. Only certain seigneurs -- those with the power of haute justice (seigeurial justice was divided into "high" "middle" and "low" justice) -- could enact the death penalty, and only with the consent of the présidiaux.

Crimes of desertion, highway robbery, and mendicants (so-called cas prévôtaux) were under the supervision of the en:prévôt des maréchaux, who exacted quick and impartial justice. In 1670, their purview was overseen by the présidiaux (see below).

The national judicial system was made-up of tribunals divided into en:bailliages (in northern France) and sénéchaussées (in southern France); these tribunals (numbering around 90 in the 16th century, and far more at the end of the 18th) were supervised by a lieutenant général and were subdivided into:

- prévôtés supervised by a en:prévôt

- or (as was the case in en:Normandy) into vicomtés supervised by a vicomte (the position could be held by non-nobles)

- or (in parts of northern France) into en:châtellenies supervised by a en:châtelain (the position could be held by non-nobles)

- or, in the south, into vigueries or baylies supervised by a viguier or a bayle.

In an effort to reduce the case load in the parlements, certain bailliages were given extended powers by en:Henri II of France: these were called présidiaux.

The prévôts or their equivalent were the first-level judges for non-nobles and ecclesiastics. In the exercise of their legal functions, they sat alone, but had to consult with certain lawyers (avocats or procureurs) chosen by themselves, whom, to use the technical phrase, they "summoned to their council". The appeals from their sentences went to the bailliages, who also had jurisdiction in the first instance over actions brought against nobles. Bailliages and présidiaux were also the first court for certain crimes (so-called cas royaux; these cases had formerly been under the supervision of the local seigneurs): sacrilege, en:lèse-majesté, en:kidnapping, en:rape, en:heresy, alteration of money, sedition, insurrections, and the illegal carrying of arms. To appeal a bailliage's decisions, one turned to the regional en:parlements.

The most important of these royal tribunals was the prévôté[4] and présidial of Paris, the Châtelet, which was overseen by the prévôt of Paris, civil and criminal lieutenants, and a royal officer in charge of maintaining public order in the capital, the Lieutenant General of Police of Paris.

上級裁判所

The following were cours souveraines, or superior courts, whose decisions could only be revoked by "the king in his conseil" (see administration section below).

- en:Parlements - eventually 14 in number: en:Paris, en:Languedoc (en:Toulouse), en:Provence (Aix), en:Franche-Comté (en:Besançon), Guyenne (en:Bordeaux), Burgundy (en:Dijon), Flanders (en:Douai), en:Dauphiné (en:Grenoble), Lorraine (en:Nancy), en:Metz (formerly one of the en:Trois-Évêchés), Navarre (Pau), en:Brittany (en:Rennes, briefly in en:Nantes), en:Normandy (en:Rouen) and (from 1523-1771) en:Dombes (en:Trévoux). There was also parlement in en:Savoy (en:Chambery) from 1537-1559. The parlements were originally only judicial in nature (appellate courts for lower civil and ecclestiacial courts), but began to subsume limited legislative functions (see administration section below). The most important of the parlements, both in administrative area (covering the major part of northern and central France) and prestige, was the parliament of Paris, which also was the en:court of first instance for peers of the realm and for regalian affairs.

- Conseils souverains - en:Alsace (en:Colmar), en:Roussillon (en:Perpignan), en:Artois (a conseil provincial, en:Arras) and (from 1553-1559) en:Corsica (en:Bastia); formerly Flanders, Navarre and Lorraine (converted into parlements). The conseils souverains were regional parliaments in recently conquered lands.

- en:Chambre des comptes - en:Paris, en:Dijon, en:Blois, en:Grenoble, en:Nantes. The chambre des comptes supervised the spending of public funds, the protection of royal lands (domaine royal), and legal issues involving these areas.

- en:Cours des aides - en:Paris, Clermont, en:Bordeaux, en:Montauban. The cours des aides supervised affairs in the pays d'élections, often concerning taxes on wine, beer, soap, oil, metals, etc.

- en:Chambre des comptes combined with Cours des aides - Aix, en:Bar-le-Duc, Dole, en:Nancy, en:Montpellier, Pau, en:Rouen

- Cours des monnaies - Paris; additionally en:Lyon (1704-1771), and (after 1766), the chambre des comptes of Bar-le-Duc and Nancy. The cours des monnaies oversaw money, coins and precious metals.

- en:Grand Conseil - created in 1497 to oversee affairs concerning ecclesiastical benefices; occasionally the king sought the Grand Conseil's intervention in affairs considered to be too contentious for the parliament.

The head of the judicial system in France was the chancellor.

行政

One of the established principles of the French monarchy was that the king could not act without the advice of his counsel; the formula "le roi en son conseil" expressed this deliberative aspect. The administration of the French state in the early modern period went through a long evolution, as a truly administrative apparatus -- relying on old nobility, newer chancellor nobility ("noblesse de robe") and administrative professionals -- was substituted to the feudal clientel system.

Under Charles VIII and Louis XII the king's counsel was dominated by members of twenty or so noble or rich families; under François I the number of counsellors increased to roughly 70 individuals (although the old nobility was proportionally more important than in the previous century). The most important positions in the court were those of the en:Great Officers of the Crown of France, headed by the connétable (chief military officer of the realm; position eliminated in 1627) and the chancellor. The royal administration in the Renaissance was divided between a small counsel (the "secret" and later "high" counsel) of 6 or fewer members (3 members in 1535, 4 in 1554) for important matters of state; and a larger counsel for judicial or financial affairs. François I was sometimes criticized for relying too heavily on a small number of advisors, while Henri II, en:Catherine de Medici and their sons found themselves frequently unable to negotiate between the opposing en:Guise and en:Montmorency families in their counsel.

Over time, the decision-making apparatus of the King's Council was divided into several royal counsels. The subcouncils of the King's Council can be generally grouped as "governmental councils", "financial councils" and "judicial and administrative councils". With the names and subdivisions of the 17th - 18th century, these subcouncils were:

Governmental Councils:

- Conseil d'en haut ("High Council", concerning the most important matters of state) - composed of the king, the crown prince (the "dauphin"), the chancellor, the contrôleur général des finances, and the secretary of state in charge of foreign affairs.

- Conseil des dépêches ("Council of Messages", concerning notices and administrative reports from the provinces) - composed of the king, the chancellor, the secretaries of state, the contrôleur général des finances, and other councillors according to the issues discussed.

- Conseil de Conscience

Financial Councils:

- Conseil royal des finances ("Royal Council of Finances") - composed of the king, the "chef du conseil des finances" (an honorary post), the chancellor, the contrôleur général des finances and two of his consellors, and the intendants of finance.

- Conseil royal de commerce

Judicial and Administrative Councils:

- Conseil d'État et des Finances or Conseil ordinaire des Finances — by the late 17th century, its functions were largely taken over by the three following sections.

- en:Conseil privé or Conseil des parties' or Conseil d'État ("Privy Council" or "Council of State", concerning the judicial system, officially instituted in 1557) — the largest of the royal councils, composed of the chancellor, the dukes with peerage, the ministers and secretaries of state, the contrôleur général des finances, the 30 councillors of state, the 80 en:maître des requêtes and the en:intendants of finance.

- Grande Direction des Finances

- Petite Direction des Finances

In addition to the above administrative institutions, the king was also surrounded by an extensive personal and court retinue (royal family, en:valet de chambres, guards, honorific officers), regrouped under the name "en:Maison du Roi".

At the death of Louis XIV, the Regent en:Philippe II, Duke of Orléans abandoned several of the above administrative structures, most notably the Secretaries of State, which were replaced by Counsels. This system of government, called the en:Polysynody, lasted from 1715-1718.

Under Henry IV and Louis XIII the administrative apparatus of the court and its councils was expanded and the proportion of the "noblesse de robe" increased, culminating in the following positions during the 17th century:

- First Minister: ministers and secretaries of state — such as Sully, en:Concini (who was also governor of several provinces), Richelieu, en:Mazarin, en:Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Cardinal de Fleury, Turgot, etc. — exerted a powerful control over state administration in the 17th and 18th century. The title "principal ministre de l'état" was however only given six times in this period and Louis XIV himself refused to chose a "prime minister" after the death of Mazarin.

- en:Chancellor of France (also called the "garde des Scéaux", or "Keeper of the Seals"; in the case of incapacity or disfavor, the Chancellor was generally permitted to retain his title, but the royal seals were passed to a deputy, called the "garde des Scéaux"[5])

- en:Controller-General of Finances (contrôleur général des finances, formerly called the en:surintendant des finances).

- Secretaries of State: created in en:1547 by Henri II, of greater importance after en:1588, generally 4 in number, but occasionally 5:

- Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Secretary of State for War, also oversaw France's border provinces.

- Secretary of State of the Navy

- en:Secretary of State of the Maison du Roi (the king's royal entourage and personal military guard), who also oversaw the clergy, the affairs of Paris and the non-border provinces.

- en:Secretary of State for Protestant Affairs (combined with the secretary of the Maison du Roi in 1749).

- Councillors of state (generally 30)

- en:Maître des requêtes (generally 80)

- en:Intendants of finance (6)

- Intendants of commerce (4 or 5)

- Ministers of State (variable)

- Treasurers

- en:Farmers-General

- Superintendent of the postal system

- Directeur général of buildings

- Directeur général of fortifications

- Lieutenant General of Police of en:Paris (in charge of public order in the capital)

- en:Archbishop of Paris

- Royal confessor

Royal administration in the provinces had been the role of the bailliages and sénéchaussées in the Middle Ages, but this declined in the early modern period, and by the end of the 18th century, the bailliages served only a judicial function. The main source of royal administrative power in the provinces in the 16th and early 17th centuries fell to the gouverneurs (who represented "the presence of the king in his province"), positions which had long been held by only the highest ranked families in the realm. With the civil wars of the early modern period, the king increasing turned to more tractable and subservient emissaries, and this was the reason for the growth of the provincial en:intendants under Louis XIII and Louis XIV. Indendants were chosen from among the en:maître des requêtes. Intendants attached to a province had jurisdiction over finances, justice and policing.

By the 18th century, royal administrative power was firmly established in the provinces, despite protestations by local parlements. In addition to their role as appellate courts, regional en:parlements had gained the privilege to register the edicts of the king and to present the king with official complaints concerning the edicts; in this way, they had acquired a limited role as the representative voice of (predominantly) the magistrate class. In case of refusal on parliament's part to register the edicts (frequently concerning fiscal matters), the king could impose registration through a royal assize ("lit de justice").

The other traditional representatives bodies in the realm were the Etats généraux (created in 1302) which reunited the three en:estates of the realm (clergy, nobility, the third estate) and the "États provinciaux" (Provincial Estates). The "Etats généraux" (convoked in this period in 1484, 1560-1, 1576-7, 1588-9, 1593, 1614, and 1789) had been reunited in times of fiscal crisis or convoked by parties malcontent with royal prerogatives (the Ligue, the Hugenots), but they had no true power, the dissensions between the three orders rendered them weak and they were dissolved before having completed their work. As a sign of French absolutism, they ceased to be convoked from 1614 to 1789. The provincial estates proved more effective, and were convoked by the king to respond to fiscal and tax policies.

教会

The French monarchy was irrevocably linked to the en:Catholic church (the formula says "la France est la fille aînée de l'église", or "France is the eldest daughter of the church"), and French theorists of the en:divine right of kings and en:sacerdotal power in the Renaissance had made these links explicit: Henry IV was able to ascend to the throne only after abjuring Protestantism. The symbolic power of the Catholic monarch was apparent in his crowning (the king was annoited by blessed oil in en:Rheims) and he was popularly believed to be able to cure en:scrofula by the laying on of his hands (accompanied by the formula "the king touches you, but god heals you").

In 1500, France had 14 archibishoprics (Lyon, Rouen, Tours, Sens, Bourges, Bordeaux, Auch, Toulouse, Narbonne, Aix-en-Provence, Embrun, Vienne, Arles, and Rheims) and 100 bishoprics; by the eighteenth century, archbishoprics and bishoprics had expanded to a total of 139 (see en:List of Ancien Régime dioceses of France). The upper levels of the French church were made up predominantly of old nobility, both from provincial families and from royal court families, and many of the offices had become de facto hereditary possessions, with some members possessing multiple offices. In addition to fiefs that church members possessed as seigneurs, the church also possessed seigneurial lands in its own right and enacted justice upon them.

Other temporal powers of the church included playing a political role as the first estate in the "États Généraux" and the "États Provinciaux" (Provincial Assemblies) and in Provincial Conciles or en:Synods convoked by the king to discuss religious issues. The church also claimed a prerogative to judge certain crimes, most notably heresy, although the Wars of Religion did much to place this crime in the purview of the royal courts and parliament. Finally, abbots, cardinals and other prelates were frequently employed by the kings as ambassadors, members of his councils (such as Richelieu and en:Mazarin) and in other administrative positions.

The faculty of theology of Paris (often called the en:Sorbonne), maintained a censor board which reviewed publications for their religious orthodoxy. The Wars of Religion saw this control over censorship however pass to the parliament, and in the seventeenth century to the royal censors, although the church maintained a right to petition.

The church was the primary provider of schools (primary schools and "colleges") and hospitals ("hôtel-Dieu", the en:Sisters of Charity) and distributor of relief to the poor in pre-revolutionary France

The en:Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges (1438, suppressed by Louis XI but brought back by the États Généraux of Tours in 1484) gave the election of bishops and abbots to the cathedral en:chapter houses and en:abbeys of France, thus stripping the pope of effective control of the French church and permitting the beginning of a Gallican church. However, in 1515, François I signed a new agreement with Pope en:Leo X, the en:Concordat of Bologna, which gave the king the right to nominate candidates and the pope the right of en:investiture; this agreement infuriated gallicans, but gave the king control over important ecclesiastical offices with which to benefit nobles.

Although exempted from the en:taille, the church was required to pay the crown a tax called the "free gift" ("don gratuit"), which it collected from its office holders, at roughly 1/20 the price of the office (this was the "décime", reapportioned every five years). In its turn, the church exacted a mandatory tithe from its parishioners, called the "dîme".

- For church history in the 16th century, see en:Protestant Reformation and en:French Wars of Religion.

The en:Counter-Reformation saw the French church create numerous religious orders (such as the en:Jesuits) and make great improvements on the quality of its parish priests; the first decades of the 17th century were characterized by a massive outpouring of devotional texts and religious fervor (exemplified in en:Saint Francis of Sales, en:Saint Vincent de Paul, etc.). Although the en:Edict of Nantes (1598) permitted the existence of prostestant churches in the realm (characterized as "a state within a state"), the next eighty years saw the rights of the en:Huguenots slowly stripped away, until Louis XIV finally revoked the edict in en:1685, producing a massive emigration of Huguenots to other countries. Religious practices which veered too close to Protestantism (like en:Jansenism) or to the mystical (like Quietism) were also severely suppressed, as too libertinage or overt en:atheism.

Although the church would come under attack in the 18th century by the philosophers of en:the Enlightenment and recruitment of clergy and monastic orders would drop after 1750, figures show that, on the whole, the population remained a profoundly Catholic country (absenteeism from services did not exceed 1% in the middle of the century[6]). At the eve of the revolution, the church possessed upwards of 7% of the country's land (figures vary) and generated yearly revenues of 150 million livres.

参考文献と脚注

Books

- (フランス語) Bély, Lucien. La France moderne: 1498-1789. Collection: Premier Cycle. Paris: PUF, 1994. ISBN 2-13-047406-3

- (フランス語) Bluche, François. L'Ancien régime: Institutions et société. Collection: Livre de poche. Paris: Fallois, 1993. ISBN 2-253-06423-8

- (フランス語) Jouanna, Arlette and Philippe Hamon, Dominique Biloghi, Guy Thiec. La France de la Renaissance; Histoire et dictionnaire. Collection: Bouquins. Paris: Laffont, 2001. ISBN 2-221-07426-2

- (フランス語) Jouanna, Arlette and Jacqueline Boucher, Dominique Biloghi, Guy Thiec. Histoire et dictionnaire des Guerres de religion. Collection: Bouquins. Paris: Laffont, 1998. ISBN 2-221-07425-4

- Kendall, Paul Murray. Louis XI: The Universal Spider. New York: Norton, 1971. ISBN 0-393-30260-1

- Knecht, R.J. The Rise and Fall of Renaissance France. London: Fontana Press, 1996. ISBN 0-00-686167-9

- Major, J. Russell. From Renaissance Monarchy to Absolute Monarchy: French Kings, Nobles & Estates. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8018-5631-0

- (フランス語) Pillorget, René and Suzanne Pillorget. France Baroque, France Classique 1589-1715. Collection: Bouquins. Paris: Laffont, 1995. ISBN 2-221-08110-2

- Salmon, J.H.M. Society in Crisis: France in the Sixteenth Century. Methuen: London, 1975. ISBN 0-416-73050-7

- (フランス語) Viguerie, Jean de. Histoire et dictionnaire du temps des Lumières 1715-1789. Collection: Bouquins. Paris: Laffont, 1995. ISBN 2-221-04810-5

Notes

Historical Era

| 先代 en:Hundred Years War | French History 1453-1789 | 次代 Revolutionary Period |