Syria

Levantine Federation | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: موطني Mawṭinī "My Homeland" | |

Location of Syria | |

| Capital | Damascus 33°30′N 36°18′E / 33.500°N 36.300°E |

| Largest city | Tel Aviv-Jaffa |

| Official languages | Arabic, Hebrew, Kurdish |

| Recognized languages | Turkish, Aramaic, Circassian, Armenian |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Syrian, Levantine |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic |

| Riyad al-Maliki | |

| George Sabra | |

| Bisher Khasawneh | |

| Uzi Vogelman | |

| Legislature | Levantine Parliament (unicameral) |

| Establishment | Independence from the Ottoman Empire |

• Kingdom | 26 November 1919 |

| 17 April 1921 | |

• Federation | 17 December 1951 |

| Area | |

• Total | 311,764 km2 (120,373 sq mi) (70th) |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | 52,781,931 (27th) |

• Density | 169.3/km2 (438.5/sq mi) (58th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | $3.046 trillion (12th) |

• Per capita | $57,714 (28th) |

| Gini (2018) |  28.5 28.5low (23rd) |

| HDI (2021) |  0.897 0.897very high (29th) |

| Currency | Levantine Dinar (LVD) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (LST) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +963 |

| ISO 3166 code | SY |

Syria, officially the Levantine Federation is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean. It is bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the southeast, and the Red Sea and Egypt to the south and southwest. Cyprus lies to the west across the Mediterranean Sea. It is a federal republic that consists of 11 cantons (subdivisions). A country of fertile plains, high mountains, and deserts, Syria is home to diverse ethnic and religious groups. Syria is a member of the Arab League and various other international groups. The capital city is Damascus, while Amman is the largest city, followed by Beirut and Tel Aviv-Jaffa. Arabs are the largest ethnic group, and Sunni Muslims are the largest religous group.

The name "Syria" comes from Assyria, an ancient civilization centered in northern Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq. Assyria was one of many civilizations and empires to control the region in whole or in part. These include, but are not limited to: Aram-Damascus, Egypt, Moab, Judah, Phoenicia, Babylonia, Persia, Rome, and the Arabs. By the late 13th centurty, Mamluk Egypt had control over the territory. However, in 1517 they were conquered by the Ottomans, who ruled over almost all of Syria for the next few hundred years. In World War I, France, Britain, and Arab rebels under the Sharif of Mecca took the territory from Ottoman hands. After the war, Faisal sucessfully appealled to Britain for the creation of the Hashemite Kingdom of Syria. France, however, attempted to invade Syria, starting a brief war between the newly established kingdom and the superpower. Suprisingly to many at the time, Syria triumphed; France, lacking British support, was forced to withdrawl fully in 1921.

After having won independence, King Faisal embarked on a campaign to modernize and develoup his new nation. New roads and railways were built, which were then connected to new ports. He partially modernized agriculture while encouraging urbanization. He also accepted Zionist immigrants, allowing them to buy land in Syria. With the fall of the Weimar Republic in Europe, and the rise of Adolf Hitler in 1933-34, Jewish emmigration from Germany increased massively, with Syria becoming an important refuge for them. As more Jews began to arrive however, the Arabs of Palestine, especially Muslims, began to consider them more of a threat, protesting and even attacking their homes and settlements. King Faisal I had to toe the line between protecting his new Jewish citizens and not angering the Arab Muslim majority in the country.

Syria remained neutral throughout the first part of World War II, joining in mid-1941. After the war, Jewish immigration reached yet another record height. Though it abated during the next few years, violence in Palestine exploded, with the king all but powerless to stop it. In 1951, the king reliquished power to parliament, resulting in the creation of the new Levantine Federation. The new constitution was drafted and signed by members of all the major ethnic and religious groups, including Muslim and Christian Arabs, Jews, Nusayrites, Kurds, Assyrians, and Druze. Syria was spared from the unstable and tumultuous times of it's neigbors, Iraq and Egypt, during the Cold War by the stablity this new constitution allowed for. Violence in Palestine continued through the 1950s and into the early 1960s, and in some ways persists to this day. However, through the creation of Jewish and Arab cantons in the region, violence decreased quite a lot, and the combined efforts of Jewish and Arab authorities, as well as the central government, quelled the worst of the terrorism and attacks on both sides.

Throughout the Cold War in the Arab world, Arab nationalists, Islamists, monarchists, Zionists, and other forces threatened to rip the country apart or descend it into a civil war. The majority of people, however, wanted to wealthy and prosperous federation to remain whole, and the country faced very little instablity compared to other states in the region. The worst challenge was the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser's popular brand of Arab nationalism. After Nasser's death in 1970, the movement decended into chaos, fracturing and its leaders fighting amongst themselves, drasticly decreasing its popularity. The Iranian Revoluton in 1979 threatened Syrian stability again, increasing Islamist thought amongst the people, especially Shi'ites, though only for a time; the country remained in tact and in relative peace through this troublesome period and into the much stabler world of today.

Syria in modern times is a prosperous hub for tourism and business, and a stable beacon of democracy in the MENA region. Through generous welfare programs and and a free society, the nation has achieved a level of wealth, both for its government and its people, that is unrivaled in the Middle East. Syria is an exporter of many goods, including oil, natural gas, wine, vegetables, meat, clothing, and electronics. It also has a large defence industry made nessesary by the tensions of the Cold War, and has been a major exporter of small arms, APCs, and IFVs; Syria has also begun exporting combat drones in recent years. Since 2003, Islamic terror has become a new challange for the Syrian security services. The Islamic State in 2014 began an invasion of Syria from western Iraq, causing a new war that would claims thousands of lives. Even after the fall of IS, small cells, both al-Qaeda affiliates and IS remnants have carried out numerous small-scale attacks, mostly in the eastern desert around Palmyra. Larger attacks, focused on major cities and especially minorities, have mostly been thwarted by Syrian security forces. Some exeptions were in the 2015 Jerusalem bus attack, and the 2016 suicide bombings across northern Syria. Since 2018, Syria has experienced far less attacks, as most of the remaining terrorist cells have been killed or captured.

Etymology

Main articles: Name of Syria, Names of the Levant

Several sources indicate that the name Syria is derived from the 8th century BC Luwian term "Sura/i", and the derivative ancient Greek name: Σύριοι, Sýrioi, or Σύροι, Sýroi, both of which originally derived from Aššūr (Assyria) in northern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq). However, from the Seleucid Empire (323–150 BC), this term was also applied to the Levant, and from this point the Greeks applied the term without distinction between the Assyrians of Mesopotamia and Arameans of the Levant. Mainstream modern academic opinion strongly favors the argument that the Greek word is related to the cognate Ἀσσυρία, Assyria, ultimately derived from the Akkadian Aššur. The Greek name appears to correspond to Phoenician ʾšr "Assur", ʾšrym "Assyrians", recorded in the 8th century BC Çineköy inscription.

Medieval Italians called the region Levante after its easterly location where the sun "rises"; this term was adopted from Italian and French into many other languages.

History

Main article: History of Syria

Prehistory and Ancient antiquity (Before 539 BC)

Anatomically modern humans are believed to have inhabited the Levant since at least 800,000 BC.

Since approximately 10,000 BC, Syria was one of the centers of Neolithic culture, where agriculture and cattle breeding first began to appear. The Neolithic is traditionally divided to the Pre-Pottery (A and B), starting around 12,000 years ago, and Pottery Late Neolithic phases, beginning around 8,500 years ago. Pre-Pottery Neolithic A developed from the earlier Natufian cultures of the area. This is the time of the Neolithic Revolution and development of agricultural economies in the Near East. In addition, the Levant in the Neolithic was involved in large scale, far reaching trade. Trade on an impressive scale and covering large distances continued during the Chalcolithic (c. 4500–3300 BCE). Obsidian found in the Chalcolithic levels north of Khirbat Futais in Palestine have had their origins traced via elemental analysis to three sources in Southern Anatolia: Hotamis Dağ, Göllü Dağ, and as far east as Nemrut Dağ, 500 km (310 mi) east of the other two sources. This is indicative of a very large trade circle reaching as far as the Northern Fertile Crescent at these three Anatolian sites.

The urban development of Canaan lagged considerably behind that of Egypt and Mesopotamia and even that of northern Syria, where from 3,500 BC a sizable city developed at Hamoukar. This city, which was conquered, probably by people coming from the Southern Iraqi city of Uruk, saw the first connections between Syria and Southern Iraq that some have suggested lie behind the patriarchal traditions. Urban development again began culminating in Early Bronze Age sites like Ebla, which by 2,300 BC, was incorporated once again into the Empire of Sargon, and then Naram-Sin of Akkad (Biblical Accad). The archives of Ebla show reference to a number of Biblical sites, including Hazor, Jerusalem, and a number of people have claimed, also to Sodom and Gomorrah, mentioned in the patriarchal records. The collapse of the Akkadian Empire, saw the arrival of peoples using Khirbet Kerak Ware pottery, coming originally from the Zagros Mountains, east of the Tigris. It is suspected by some Ur seals that this event marks the arrival in Syria of the Hurrians, people later known in the Biblical tradition possibly as Horites.

The following Middle Bronze Age period was initiated by the arrival of "Amorites" from Syria into Southern Iraq, an event which some associated with the arrival of Abraham's family in Ur. This period saw the pinnacle of urban development in the area of Syria. Archaeologists show that the chief state at this time was the city of Hazor, which may have been the capital of the land of Israel. This is also the period in which Semites began to appear in larger numbers in the Nile delta region of Egypt.

The Early Bronze Age period was dominated by the East Semitic-speaking kingdoms of Ebla, Nagar and the Mari. Ebla has been described as the world's first recorded superpower, controlling much of present-day Syria. At its greatest extent, Ebla controlled an area roughly a quarter the size of modern Syria, from Ursa'um in the north, to the area around Damascus in the south, and from Phoenicia and the coastal mountains in the west, to Haddu in the east, and had more than sixty vassal kingdoms and city-states. Scholars believe the language of Ebla to be among the oldest known written Semitic languages after Akkadian. Ebla was weakened by a long war with Mari, and the whole of Syria became part of the Mesopotamian Akkadian Empire after Sargon of Akkad and his grandson Naram-Sin's conquests ended Eblan domination over Syria in the first half of the 23rd century BC.

The Akkadian Empire ruled northern parts of Syria until it collapsed due to the 4.2 kya aridification event. The event prompted large-scale movement of population from Upper Mesopotamia towards the Levant and Lower Mesopotamia, which brought about many Amorites to Sumer, and correlates with a subsequent influx and settlement expansion in many regions of Syria.

In northern Mesopotamia, the Amorite warlord Shamshi-Adad I conquered much of Assyria and formed the large, though short-lived Kingdom of Upper Mesoptamia. In the Levant, Amorite dynasties ruled various kingdoms of Qatna, Ebla and Yamhad, which also had a significant Hurrian population. Mari was similarly ruled by the Amorite Lim dynasty which belonged to the pastoral Amorites known as the Haneans, who were split into the Banu-Yamina (sons of the right) and Banu-Simaal (sons of the left) tribes. Mari was in direct conflict with another Semitic peoples, the Suteans who inhabited nearby Suhum.

By the 16th and 15th centuries bc, most of the major urban centers in the Levant had been overran and went into steep decline. Mari was destroyed and reduced in a series of wars and conflicts with Babylon, while Yamhad and Ebla were conquered and completely destroyed by Hittite king Mursili I in about 1600 bc. In northern Mesopotamia, the era ended with the defeat of the Amorite states by Puzur-Sin and Adasi between 1740 and 1735 bc, and the rise of the native Sealand Dynasty. In Egypt, Ahmose I managed to expel the Levantine Hyksos rulers from power, pushing Egypt's borders further into Canaan. The Amorites were eventually absorbed by another West Semitic-speaking people known collectively as the Ahlamu. The Arameans rose to be the prominent group amongst the Ahlamu, and from c. 1200 bc on, the Amorites disappeared from the pages of history.

Between 1550 and 1170 bc, much of the Levant was contested between Egypt and the Hittites.

During the 12th century BC, between c. 1200 and 1150, all of these powers suddenly collapsed. Centralized state systems collapsed, and the region was hit by famine. Chaos ensued throughout the region, and many urban centers were burnt to the ground by famine-struck natives and an assortment of raiders known as the Sea Peoples, who eventually settled in the Levant. The Sea Peoples' origins are ambiguous and many theories have proposed them to be Trojans, Sardinians, Achaeans, Sicilians or Lycians. The Hittite empire was destroyed, and its capital Tarḫuntašša was razed to the ground. Egypt repelled its attackers with only a major effort, and over the next century shrank to its territorial core, its central authority permanently weakened.

Aramaeans came to dominate much of Syria, establishing kingdoms and tribal polities throughout the land. Accompanied by the Suteans, the Aramaeans overran large parts of Mesopotamia around 1100 BC bar Assyria itself. It was around this time that Assyrian texts of the 9th century BC first mention the Arabs (Aribi), who inhabited swaths of land in the Levant and Babylonia. Their presence intermingled with the Aramaeans, and they are variously mentioned in the Babylon border region, Orontes valley, Homs, Damascus, Hauran, Bekaa valley in Lebanon and Wadi Sirhan, where the Arab king Gindibu of Qedar ruled from. One such example is the land of Laqē near Terqa, mentioned in a inscription by Adad-nirari II (911–891 BC), where Aramaean and Arab clans formed a confederacy.

Further west, the Levantine coast was settled by the Sea Peoples, notably the Philistines around today's Gaza Strip. The Phoenician city-states in Canaan managed to escape the destruction that ensued in the Late Bronze age collapse, and developed into commercial maritime powers with established colonies across the Mediterranean Sea.

In the southern Levant, new Canaanite groups emerged in the southern Levant during early Iron Age. In Palestine, the Israelites gradually established many small communities that dotted the central highlands, while the Philistines, a group of Aegean immigrants arrived in the southern shore of Canaan around 1175 BCE and settled there. In Transjordan, three Canaanite kingdoms—Moab, Ammon and Edom—began to arose at about the same period. The 10th and 9th centuries BCE saw the emergence of several territorial kingdoms in the southern Levant. Two Israelite kingdoms emerged: the Kingdom of Israel, which ruled over the areas of Samaria, Galilee, Sharon and parts of Transjordan, and had its capital for the most of its history in the city of Samaria, and the Kingdom of Judah, which controlled the Judaean Mountains, most of the Shfela, and the northern Naqab, and had its capital in Jerusalem.

Unlike Egypt and Mesopotamia, the Iron age Levant was characterized by patches of scattered kingdoms and tribal confederations which originated from the same cultural and linguistic milieu, and was much less densely populated than either. Occasionally, these closely related entities united against expanding outer forces. The Assyrians only managed to subdue the Levantine states after multiple attempts and campaigns, finalized under Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC).

At their height, the Assyrians dominated all of the Levant, Egypt, and Mesopotamia, and sponsored the Scythians under Madyes, their half-Assyrian king, in West Asia. However, the empire began to collapse toward the end of the 7th century BC, and was obliterated by an alliance between a resurgent Chaldean New Kingdom of Babylonia and the Iranian Medes. After the Battle of Carchemish, Nebuchadnezzar II besieged Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple (597 BC), starting the period of the Babylonian captivity, which lasted about half a century. Nebuchadnezzar also besieged the Phoenician city of Tyre for 13 years (586–573 BC), setting one of the longest sieges in history. The subsequent balance of power was, however, short-lived. In the 550s BC, the Achaemenids revolted against the Medes and gained control of their empire, and over the next few decades annexed the realms of Lydia, Damascus, Babylonia, and Egypt into their empire, consolidating control as far as India. This vast kingdom was divided up into various satrapies and governed roughly according to the Assyrian model, but with a far lighter hand.

Classical antiquity (539 BC - 636 AD)

Achaemenid Empire took over the Levant after 539 BC, but by the 4th century the Achaemenids had fallen into decline. The Phoenicians frequently rebelled against the Persians, who taxed them heavily, in contrast to the Judeans who were granted return from the exile by Cyrus the Great. Alexander the Great conquered the Levant in 333-332 BC. However, Alexander did not live long enough to consolidate his realm, and soon after his death in 323 BC, the greater share of the east eventually went to the descendants of Seleucus I Nicator.

When Alexander and later the Diadochi came to Syria, unlike Egypt, they found a sparsely populated region with no major urban center, most of which had been abandoned following the Bronze Age collapse or destroyed by the Assyrians. Alexander and his Seleucid successors founded many urban centers in the area and moved in locals and troops into the cities. The Seleucids also sponsored Greek settlement to the area. Koine Greek was largely used for administration, whereas Aramaic remained the lingua franca for much of the region and even the Hellenistic urban centers, where bilingualism was prevalent.

The Seleucids gradually lost their domains in Bactria to the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and in Iran and Mesopotamia to the rising Parthian Empire. Eventually, this limited Seleucid domains to the Levant, and the power decline would lead to the formation of several breakaway states in the Levant. The Maccabean Revolt in Palestine inaugurated the Hasmonean kingdom in 140 BC.

The Romans gained a foothold in the region in 64 BC after permanently defeating the Seleucids and Tigranes. Pompey deposed to the last Seleucid king Philip II Philoromaeus, and incorporated Syria into Roman domains. However, the Romans only gradually incorporated local kingdoms into provinces, which gave them considerable autonomy in local affairs. The Herodian Kingdom of Judea replaced the Hasmonians in 37 BC until their full incorporation of the province of Judaea in 44 AD after Herod Agrippa II. Commagene and Osroene were incorporated in 72 and 214 AD respectively, while Nabatea was incorporated as Arabia Petraea in 106 AD.

The first to second centuries saw the emergence of a plethora of religions and philosophical schools. Neoplatonism emerged with Iamblichus and Porphyry, Neopythagorianism with Apollonius of Tyana and Numenius of Apamea, and Hellenic Judaism with Philo of Alexandria. Christianity initially emerged as a sect of Judaism and finally as an independent religion by the mid-second century. Gnosticism also took significant hold in the region.

The region of Palestine or Judea experienced abrupt periods of conflict between Romans and Jews. The First Jewish–Roman War (66-73) erupted in 66, resulting in the destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple in 70. Province forces were directly engaged in the war; in 66 AD, Cestius Gallus sent the Syrian army, based on Legio X Fretensis and Legio XII Fulminata reinforced by vexillationes of IV Scythica and VI Ferrata, to restore order in Judaea and quell the revolt, but suffered a defeat in the Battle of Beth Horon. However, XII Fulminata fought well in the last part of the war, and supported its commander Vespasian in his successful bid for the imperial throne. Two generations later, the Bar Kokhba revolt (132-136) erupted once again, after which the province Syria Palaestina was created in 132.

During the Crisis of the Third Century, the Sassanids under Shapur I invaded Syria and captured Roman emperor Valerian in the Battle of Edessa. A Syrian notable of Palmyra, Odaenathus assembled the Palmyrene army and Syrian peasants, and marched north to meet Shapur I. The Palmyrene monarch fell upon the retreating Persian army between Samosata and Zeugma, west of the Euphrates, in late summer 260, defeating and expelling them. Odaenathus was succeeded by his son Vaballathus under the regency of his mother Queen Zenobia. In 270, Zenobia detached from Roman authority and declared the Palmyrene Empire, rapidly conquering much of Syria, Egypt, Arabia Petraea and large parts of Asia Minor, reaching present-day Ankara. However, by 273, Zenobia was decisively defeated by Aurelian and his Arab Tanukhid allies in Syria.

With the consolidation of Christianity, Jews had become a minority in southern Levant, remaining a majority only in Southern Judea, Galilee and Golan. Jewish revolts had also become much rarer, mostly with the Jewish revolt against Constantius Gallus (351–352) and Jewish revolt against Heraclius (617). This time the Samaritans, whose population swelled to over a million, insurrected the Samaritan revolts (484–572) against the Byzantines, which killed an estimated 200,000 Samaritans, after the civil uprising of Baba Rabba and his subsequent execution in 328/362. The devastating Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 ended with Byzantine recapture of the land, but left the empire rather exhausted, which taxed the inhabitants heavily. The Levant became the frontline between the Byzantines and the Persian Sassanids, which devastated the region.

Middle Ages (636 - 1516)

Eastern Roman control over the Levant lasted until 636 when Arab armies conquered the Levant, after which it became a part of the Rashidun Caliphate and was known as Bilād ash-Shām.

Under the Umayyads, the capital was moved to Damascus. However, the Levant did not experience wide-scale Arabian tribal settlement unlike in Iraq, where the focus of Arabian tribal migration was. Archaeological and historical evidence strongly suggest there was smooth population continuity and no large-scale abandonment of major sites and regions of the Levant after the Muslim conquest. Moreover, in contrast to Iran, Iraq and North Africa, where Muslim soldiers established separate garrison cities (amsar), Muslim troops in the Levant settled alongside locals in pre-existing cities such as Damascus, Homs, Jerusalem and Tiberias. Abbasid focus on Iraq and Iran neglected the Levant, which in turn experienced a period of frequent uprisings and revolts. Syria became fertile grounds for anti-Abbasid sentiments, in various contrasting pro-Umayyad and pro-Shiite forms. In 841, al-Mubarqa lead a rebellion against the Abbasids in Palestine, declaring himself the Umayyad Sufyani. In 912, a revolt against the Abbasids arose in the Damascus region, this time by an Alid descendant of tenth Shiite Imam Ali al-Hadi.

Arabic – made official under Umayyad rule – became the dominant language, replacing Greek and Aramaic of the Byzantine era. In 887, the Egypt-based Tulunids annexed Syria from the Abbasids, and were later replaced by once the Egypt-based Ikhshidids and still later by the Hamdanids originating in Aleppo founded by Sayf al-Dawla. Seljuk expansion into eastern Anatolia triggered the Byzantine–Seljuk wars, with the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 marking a decisive turning point in the conflict in favour of the Seljuks, undermining the authority of the Byzantine Empire in the remaining parts of Anatolia and gradually enabling the region's Turkification. The Seljuk Empire united the fractured political landscape in the non-Arab eastern parts of the Muslim world.

During the late 11th century, in response to the rise of the Sejuk Turks, European Christians launched a series of Crusades on Muslim lands, especially Syria. Sections of Syria were held by French, English, Italian and German overlords between 1098 and 1291 AD during the Crusades and were known collectively as the Crusader states among which the primary one was the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The coastal mountainous region was also occupied in part by the Nizari Ismailis, the so-called Assassins, who had intermittent confrontations and truces with the Crusader States.

After a century of Seljuk and Christian rule, Syria was largely conquered (1175–1185) by the Kurdish liberator Salah ad-Din, founder of the Ayyubid dynasty of Egypt. Aleppo fell to the Mongols of Hulegu in January 1260, and Damascus in March, but then Hulegu was forced to break off his attack to return to China to deal with a succession dispute.

A few months later, the Mamluks arrived with an army from Egypt and defeated the Mongols in the Battle of Ain Jalut in Galilee. The Mamluk leader, Baibars, made Damascus a provincial capital. When he died, power was taken by Qalawun. In the meantime, an emir named Sunqur al-Ashqar had tried to declare himself ruler of Damascus, but he was defeated by Qalawun on 21 June 1280, and fled to northern Syria. Al-Ashqar, who had married a Mongol woman, appealed for help from the Mongols. The Mongols of the Ilkhanate took Aleppo in October 1280, but Qalawun persuaded Al-Ashqar to join him, and they fought against the Mongols on 29 October 1281, in the Second Battle of Homs, which was won by the Mamluks.

In 1400, the Muslim Turco-Mongol conqueror Tamurlane invaded Syria, in which he sacked Aleppo, and captured Damascus after defeating the Mamluk army. The city's inhabitants were massacred, except for the artisans, who were deported to Samarkand. Tamurlane also conducted specific massacres of the Aramean and Assyrian Christian populations, greatly reducing their numbers. By the end of the 15th century, the discovery of a sea route from Europe to the Far East ended the need for an overland trade route through Syria.

Ottoman Syria (1516 - 1920)

Main article: Ottoman Syria

In 1516, the Ottoman Empire invaded the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt, conquering Syria, and incorporating it into its empire. The Ottoman system was not burdensome to Syrians because the Turks respected Arabic as the language of the Quran, and accepted the mantle of defenders of the faith. Damascus was made the major entrepot for Mecca, and as such it acquired a holy character to Muslims, because of the beneficial results of the countless pilgrims who passed through on the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca.

Ottoman administration followed a system that led to peaceful coexistence. Each ethno-religious minority—Arab Shia Muslim, Arab Sunni Muslim, Aramean-Syriac Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, Maronite Christians, Assyrian Christians, Armenians, Kurds and Jews—constituted a millet. The religious heads of each community administered all personal status laws and performed certain civil functions as well. In 1831, Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt renounced his loyalty to the Empire and overran Ottoman Syria, capturing Damascus. His short-term rule over the domain attempted to change the demographics and social structure of the region; he brought thousands of Egyptian villagers to populate the plains of Southern Syria, rebuilt Jaffa and settled it with veteran Egyptian soldiers aiming to turn it into a regional capital, and he crushed peasant and Druze rebellions and deported non-loyal tribesmen. By 1840, however, he had to surrender the area back to the Ottomans.

From 1864, Tanzimat reforms were applied on Ottoman Syria, carving out the provinces (vilayets) of Aleppo, Zor, Beirut and Damascus; the Mutasarrifate of Mount Lebanon was created as well, and soon after, the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem was given a separate status.

During World War I, the Ottoman Empire entered the conflict on the side of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It ultimately suffered defeat and loss of control of the entire Near East. During the conflict, genocide against indigenous Christian peoples was carried out by the Ottomans and their allies in the form of the Armenian genocide and Assyrian genocide, of which Deir ez-Zor, in Ottoman Syria, was the final destination of these death marches. During the later part of the war, Ottoman Syria was occupied by Arab forces inland, joined by British and French units along the coast. In August 1917, Great Britain officially recognized the Hashemite Kingdom of Syia, under King Faisal I.

France, however, lauched an invasion of Syria on 8 March 1920. Despite many predictions that Syria would be quickly overcome by the French Empire, Syria prevailed at the Battle of Maysaloun. Following this, France withdrew to Lebanon, where the local Christians were becoming less supportive of France due to Faisal's intention to establish a secular state. In late November 1920, the United Kingdom sent a telegram to the French Prime Minister to withdraw from Syria and establish relations with their govenment. Seing the diplomatic situation was against them, and with Syrian raids increasing in both agressiveness and effectiveness, France withdrew over the course of the next few months. The last French soldier left Beirut on 17 April 1921.

With the Ottoman surrender in 1918, Syria was able to take control over the north, including Aleppo and Antioch. During the Turkish War of Independence, Syria lost some of the cities they hoped to gain even further north, such as Urfa and Antep. Still, they had achieved independence from the great powers, a feat few nations could boast of.

Independent monarchy (1920 - 1951)

King Faisal created a parliament and worked to create a new constitution, which was signed by the leaders of all major political forces in the country, including minorities such as Kurds and Jews, on 27 November 1920. The constitution provided for a relatively weak parliament, angering many liberals and socialists, who felt the king had too much power. Dispite these concerns, the country remained remakably stable during and after the first elections in 1922. On 27 February, Hashim al-Atassi and his People's Party were elected. Dispite this, Faisal had almost all the real power in the country, especially since al-Atassi largely suppoted his rule.

From the 1920s to his death in 1933, Faisal embarked on a massive moderniztion process similar to, and at times inspired by, Atatürk's reforms in Turkey, though it differed in being more liberal and less ethno-nationalist. He somewhat secularized the country, focusing on unity between the various religions in Syria. The King also supported peace between the different ethnic groups in the country. This was especially meaningful, as the Kurds had revolted in every country they viewed as occuping their land, exept Syria. King Faisal also modernized education, focusing on the secular French model. New roads were built to connect the country as old ones were modernized. Railways were built, connecting major cities both inland and running along the coast. Ports were expanded, and they began industrializing on a scale that rivals even Turkey during this same period. New arms manufactories were made, and they formed a combat-capable navy by 1930.

In 1928, King Faisal agreed to allow the Jews to buy land in Syria, and the government began giving out land grants for Jews in Palestine. Beginning in 1932, and continually reaching record heights for the next 14 years, Jews began immigrating to Palestine en massé to remove themselves from an increasingly anti-semetic Germany, and were later joined by Jews from other parts of Europe fleeing World War II and the Holocaust.

On 8 September 1933, King Faisal died, and was succeeded by his eldest son, Ghazi. He ruled as King for the next six years, continuing his fathers reforms and trying to create peace in Palestine, to little avail. Syria was finally admited to the League of Nations on 29 April 1936. On 4 April 1939, Ghazi was assassinated by an Islamist from Palestine named Khalid al-Faraj. Ghazi was succeeded by his son Faisal II, though true power now layed with his regent, Abd al-llah; just months later, WWII began in Europe.

For a time, things stayed much the same in Palestine. The Second World War saw the neutral, but pro-allied government link anti-semetic attacks to German alliegence. The Arab leaders in Palestine however, believed that the Jews were planning to seize all Arab and Muslim lands, and kill any who resisted. Amin al-Husseini, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, frequently made anti-semetic comments and encouraged Arabs to attack Jews, even expressing sympathy for Nazi Germany. The government decided against arresting him, worringing that may cause a Palestinian Arab rebellion, or revolution by the Muslim Arabs across Syria. In 1941, al-Husseini visited Nazi Germany, met with Joachim von Ribbentrop and Adolf Hitler, and spoke to Muslim SS units.

Just months after this, the Golden Square under Rashid Gaylani launched a coup to overthrow the Iraqi government. In response, the United Kingdom demanded Syria allow British forces to invade Iraq from the west. To counter this and preserve Syrian sovreignty, Abd al-llah decided to invade Iraq alongside Britain. Churchill accepted, and Iraq was defeated in just two weeks. Following this, Syria offically declared war on Germany. Al-Husseini was arrested for treason, and put on public trial in Jerusalem. Al-Husseini's supporters protested and rioted in the streets across not just Jerusalem, but also Syria in general; many attacks on Jewish towns and settlements were recorded during this time. Due to this pressure, al-llah agreed to release al-Husseini on the condition that he never leave the country. Syria played a role in the North Africa campaign, though their forces would only take limited part in the fighting in Europe, sending one division to the Italian Front in 1943.

After the war had ended, tens of thousands of Jews left Europe for Syria, and Palestine in particular. Due to this mass immigration, inter-communal violence exploded, brought on mainly by Arab attacks and Jewish reprisals of equally brutal measure. Government forces attempted to quell the fighting, but it was unabating for several more years. Abd al-llah attempted to keep control through increasingly authoritarian methods, and the elected officials were becoming ever more angry, especially as they began to be sidelined even more. Due to this pressure, Abd al-llah gave up control to the King's cousin Prince Mohammad. The King finally abdicated on 17 December 1951. This marked the beginning of the new democratic republic, as elected officials and politcal activists from across the country came to Damascus to draft a new, more liberal constitution.

Early federation and Cold War (1951 - 1987)

Following the creation of a new constitution, the Levantine Federation had its first elections on 27 February 1952, won narrowly by al-Atassi. The new government made it a top priority to slow, and eventually stop, violence in Palestine. To do this, they decided to create a Jewish and Arab canton in the region, while people of either ethnicity would still be able to live in either canton. They also created new security forces, and gave more funding to local police. Over the next decade, violence would decrease massively, and civil war was narrowly avoided.

1952 in Egypt saw the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser, an Arab nationalist who would go on to become one of, if not the most popular and influential politicians of the Arab world. His rise to power marked the beginning of the Arab Cold War, a time of tension between monarchies such as Saudi Arabia and Morocco, and Arab nationalist regimes like Egypt and later Libya. Syria was largely neutral in the conflics that took place during this time, though they tended to side politically with the monarchies due to their mutual relationship with the United States.

The worst effect of the Cold War in Syria, was internal. Political tensions rose massively between Arab nationalists and liberals, and later Islamists. Many Arabs, mainly poorer urban ones, supported Nasser, while Bedouins were largely Islamist. Minorities, especially Jews and Kurds, almost always sided with liberals, along with most upper and middle-class Arabs. The response from the largely liberal govenments of this time was to expand the welfare state to bring more people out of poverty and, the hope was, make them less socialist. While there were many outbursts of political violence, such as in 1963, the democratic system held strong during this troublesome time.

During the late 1960s, and continuing to the present, Syria became a major hotspot for tourism. Its many beaches, historical buildings, and religous significance made it a top destination for all sorts of people from all over the world. While never a member of NATO, Syria maintained a close and friendly relationship with the United States and Western World in general. The Syrian arms industry became a major producer of weapons for many NATO and US-friendly Middle Eastern countries. The 1970s represent a very stable time in the federation's history. The war in North Yemen ended in 1969, with Nasser dying the next year, and there was relative calm in the Middle East for another decade. Arab nationalist sentiment began to decrease after this point, already weakened by the chaos it had brought to Iraq. The government took this time to invest more in the civilian economy and began sponsering a new program to give housing to the homeless. This helped reduce political tensions further.

However, a new force would begin its rise in 1979, with the Iranian Revolution and replacal of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi with Ruhollah Khomenei's Islamists. The creation of the Islamic Republic of Iran marked a turning point in Middle Eastern politics, shifting the revolutionary spirit away from Arab nationalism and giving new life to the ideas of political Islam. During the 1980s, many Bedouins, Palestinian Arabs, and rural Arabs across Syria began flocking to these ideals. Though they never won more than a third of seats in parliament, their acceptance of violence by many in the movement caused fear among the government and people alike. They started to sharply decrease in popularity after the 1986 Damascus car bomb attack, and the response of the Islamic Dawa Party - Syria that led many to believe they endorsed it, though they deny such accusations to this day. Much of their original popularity came from the People's Party's neoliberal stance after the 1977 elections. In 1987, they were defeated by the more left-wing Syrian Democratic People's Party.

Post Cold War challenges (1987 - present)

In 1990, Saddam Hussein's Iraq invaded and conquered Kuwait, beginning the Gulf War. Syria immediately condemned the invasion, and during the war launched airstrikes and raids into Iraq. As the war developed in the Coalition's favor, Syria expanded the attacks and took the cities of Qa'im, Rutba, Haditha, and Sinjar; they were also in range of Mosul and Ramadi by the war's end. After the war, Syria left all Iraqi territory. During the 1991 uprisings, nearly 200,000 Kurds fled to Syria, where they recieved refuge and assistance. Syria also participated in Operation Provide Comfort, airdroping supplies and helping to enforce the no-fly zone over northern Iraq, and later participating in Operation Northern Watch.

Despite the conflict with Iraq, internally, Syria was largely peaceful after the end of the Gulf War. Helped along by the global economy, Syria experienced an economic boom in this time, from the early 1990s to 2007. More infrastructure was built, and the government spent more money subsidizing the IT sector.

In 2001, the United States suffered an unprecedented terrorist attack on its soil. Following this attack the US demanded countries around the world to choose between supporting them, or being considered allies of terrorism. Syria, always being a close partner to America, publically sided with them. They supported the invasion and subsequent occupation of Afghanistan, though they never sent soldiers. In 2003, the US invaded and occupied Iraq. Syria, like France and many other countries, didn't support the invasion, although they would go on to help with logistics as the war intensified.

Beginning in 2007, and finally being completed in 2011, the United States withdrew from Iraq, hoping the government could keep the situation stable. This withdraw occured around the time the Arab Spring began, which saw protests across the Arab world, and in Muslim countries in general. Syria remained mostly stable during this period, as the people had little complaints. Iraq, on the other hand, further decended into chaos as protests gripped the country. This culminated in December 2013, when the newly formed Islamic State launched a rebellion against the Iraqi government. They were quickly joined by disgruntled Arab tribesmen and Saddam Hussein loyalists, and their numbers grew massively in the first few months of the rebellion.

Almost from the beginning of the conflict, IS launched raids and terrorist attacks into Syria. In July 2014, after having taken control over much of western Iraq, they invaded Syria. The Islamists were quickly pushed back, and in just a few weeks, Syrian forces had entered Iraq. Despite this, it would take many more years to fully end the insurgency in the desert. In early 2015 the Islamic State began to be pushed back by Iraqi government forces, the Syrian military, and a multi-national coalition. They lost most of their holdings in the Middle East by December of that year, shifting their focus mainly to Somalia, Libya, and West Africa in general.

During the war and in the following years, Syria experienced numerous terrorist attacks carried out mainly by the Islamic State. Some of these include the 2015 Jerusalem bus attacks, and the 2016 bombings in Damascus and across the north of Syria. The Syrian Security Forces have in the past prevented and stopped many terrorist attacks, and their military fully put down the IS insurgency in 2018.

Despite the many challenges the state has been forced to undure, the Levantine Federation remains a stable and prosperous democracy in the heart of an unstable and autocratic region. The nation is considered one of the greatest post-colonial successes for its many achiements in science, art, and statecraft.

Geography

Syria is a Middle Eastern country, lying at the eastern edge of the Mediterranean. The country is bounded in the north by Turkey, to the east by Iraq, to the southeast by Saudi Arabia, and to the south and southwest by the Red Sea and Egypt. Syria lies between latitudes 29° and 38° N, and longitudes 34° and 43° E. The climate varies from the humid Mediterranean coast, through a semiarid steppe zone, to arid desert in the east. Important agricutural areas include the Jazira region in the northeast, Hawran south of Damascus to the region of Transjordan, most of northern Palestine, western parts of Transjordan along the Jordan River Valley, and some parts of the Lebanon. The Eurphrates cuts through the country in the northeast, while the Jordan River flows through Syria in the south, into the Dead Sea. The country is an important part of the Fertile Crescent. Its land stradles the northwestern part of the Arabian Plate.

The country first struck petroleum in 1956; since then numerous oil deposits have been found. Oil is mostly concentrated around al-Hasakah and Deir ez-Zor in the north (natural extentions of the Iraqi oil fields around Mosul and Kirkuk), and in the south, in the Negev and the southwestern deserts of Transjordan. Natural gas has been discovered off the coast, and inland sites such as the field of Jbessa, discovered in 1940.

Biodiversity

Syria contains five terrestrial ecoregions: Syrian xeric grasslands and shrublands, Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests, Southern Anatolian montane conifer and deciduous forests, Mesopotamian shrub desert, and the Arabian Desert. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 3.76, ranking it 141st globally out of 172 countries.

Climate

Temperatures in Syria vary widely, especially during the winter. Coastal areas, such as those of Tel Aviv and Beirut, have a typical Mediterranean climate with cool, rainy winters and long, hot summers. The northern Negev and more inland regions have a semi-arid climate with hot summers, cool winters, and fewer rainy days than the Mediterranean climate. The outlying desert areas have a desert climate with very hot, dry summers, and mild winters with few days of rain. The highest temperature in the world outside Africa and North America as of 2021, 54 °C (129 °F), was recorded in 1942 in the Tirat Zvi kibbutz in the northern Jordan River valley.

At the other extreme, mountainous regions can be windy and cold, and areas at elevation of 750 metres (2,460 ft) or more (same elevation as Jerusalem) will usually receive at least one snowfall each year. From May to September, rain in Syria is rare. With scarce water resources in many regions, Syria has developed various water-saving technologies, including drip irrigation. Syrians also take advantage of the considerable sunlight available for solar energy, making Syria a leading nation in solar energy use per capita—many houses across the country use solar panels for water heating.

The Syrian Ministry of Environmental Protection has reported that climate change "will have a decisive impact on all areas of life, including: water, public health, agriculture, energy, biodiversity, coastal infrastructure, economics, nature, national security, and geostrategy", and will have the greatest effect on vulnerable populations such as the poor, the elderly, and the chronically ill.

Government and politics

The Levantine Federation is a federal democratic republic with a unicameral legislature. The country has a parliamentary system, proportional representation and universal suffrage. A member of parliament supported by a parliamentary majority becomes the prime minister—usually this is the chair of the largest party. The prime minister is the head of government and head of the cabinet.

The Syrian Parliament is composed of 200 MPs elected via proportional representation, with a 3% threshold. The country has a few main parties, meaning that coalitions are usually required. Elections are schedualed for every 5 years, though they can happen sooner if the ruling coalition collapses or a vote of no confidence passes.

The President of Syria is head of state, with largely ceremonial duties.

The constitution created in 1952 ensures that no one ethnic or religious group can have total control, and grants equal rights and protection under the law to all citizens. Muslim Arabs make up a large majority of the population, and so have a major role in the country's politics however. This has led minorities, especially the Jews and Kurds, to seek greater autonomy and for some, outright independence.

Legal System

Syria has a four-tier court system. At the lowest level are magistrate courts, situated in most cities across the country. Above them are district courts, serving as both appellate courts and courts of first instance; they are situated in Syrian districts. Above district courts are cantonal courts, with one situated in each canton. The third and final tier is the Supreme Court in Damascus; it serves a dual role as the highest court of appeals and the High Court of Justice. In the latter role, the Supreme Court rules as a court of first instance, allowing individuals, both citizens and non-citizens, to petition against the decisions of state authorities.

Syrian law is based mostly on English common law and French civil code, with elements of Sharia law. It is based on the principle of stare decisis (precedent) and is an adversarial system, where the parties in the suit bring evidence before the court. Court cases are decided by professional judges with no role for juries.

Administrative divisions

Syria is split into 11 cantons: Rojava, Aleppo, Latakia, Homs, Damascus, Druzia, Lebanon, Jewish Palestine, Arab Palestine, Jerusalem, and Transjordan. Two of these, Jerusalem and Damascus, are cities with enough signifigance to warant their own cantons.

| Canton | Capital | Largest City | Population, 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arab P. | Nablus | Gaza | 9,679,454 |

| Aleppo | Aleppo | Aleppo | 4,282,674 |

| Damascus | Damascus | Damascus | 2,832,154 |

| Druzia | as-Suwayda | as-Suwayda | 1,573,565 |

| Homs | Homs | Homs | 4,274,163 |

| Jerusalem | Jerusalem | Jerusalem | 2,253,577 |

| Jewish P. | Tel Aviv-Jaffa | Tel Aviv-Jaffa | 7,537,294 |

| Latakia | Latakia | Latakia | 2,973,239 |

| Lebanon | Beirut | Beirut | 6,296,814 |

| Rojava | al-Hasakah | al-Hasakah | 1,274,285 |

| Transjordan | Amman | Amman | 9,531,712 |

Foreign relations

Main article: Foreign Relations of Syria

Syria has been a close ally of the United States and Western World since the start of the Cold War, and has enjoyed very close relations with the US and with EU member states. Dispite their conflict during the Turkish War of Independence, Turkey and Syria have since kept a friendly relationship with one another; Recep Tayyip Edoğan's leadership has at times challenged this friendship, however.

Much of the country's foreign focus has been the creation of a wide bulwark against Iran. To do this, Syria has formed strong relations with the Gulf monarchies and Egypt. Iran, for its part, has sponsered numerous terrorist groups across the region, most notably with the Houthis in Yemen. Syria has friendships with Morocco, Tunisia, and Armenia as well; in part due to anti-Iran unity, but also because of the close relationships the people of these nations have with one another.

Syria is a founding member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and of the Arab League. It enjoys "advanced status" with the European Union and is part of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which aims to increase links between the EU and its neighbours.

Military

Main article: Leventine Armed Forces

The Levantine army grew out of the Arab rebels who defeated the Ottoman Empire during World War I. It was first organized in 1920 into the Royal Syrian Army. During the reforms of the 1920s and '30s, the Royal Syrian Navy was developed and made into a real fighting force. The air force was created around the same time, and during World War II bought a large number of Spitfires from the British. After the abdication of King Faisal, the military arms took on their present names: the Levantine Army, Levantine Navy, and Levantine Air Force.

The forces, especially the army, have long been lauded for their professionalism and displine; a rare sight in Middle Eastern militaries. The military enjoys strong support and aid from the United States, United Kingdom, and France. This is in large part due to Syria's critical position in the Middle East. The development of Special Operations Forces has been particularly significant, enhancing the capability of the military to react rapidly to threats to homeland security, as well as training special forces from the region and beyond. Syria provides extensive training to the security forces of several Arab countries. The army currently has around 380,000 personnel.

The country's military-industrial complex is also very developed, as the country has been near constantly threatened by outside powers since the Cold War. Syria has created a number of high-quality armored vehicles in the past such as the Arlaba, Samid, and Fahd. They also produce small-arms designs like the Tavor Bullpup Assault Rifle.

There are about 52,000 Levantine troops working with the United Nations in peacekeeping missions across the world. Syria ranks third internationally in participation in U.N. peacekeeping missions, with one of the highest levels of peacekeeping troop contributions of all U.N. member states. The nation has dispatched several field hospitals to conflict zones and areas affected by natural disasters across the region. Since 2014, Syria has been directly involved in the War on Terror, though its role has diminished since 2018.

Law enforcement

Main article: Law enforcement in Syria, Leventine police

Syria's law enforcement is under the control of the Levantine Ministry of Public Safety, and by extension, the Ministry of Internal Affairs. There are numerous police departments across the country, including municipal police departments, district offices, cantonal police, and federal law enforcement.

The number of female police officers is rising, being the first Middle Eastern country to allow them in the 1970s. Syria's law enforcement is ranked 29th globally and 1st in the Middle East, in terms of police services' performance, by the 2016 World Internal Security and Police Index.

Economy

Syria is considered the most advanced country in the Middle East in economic and industrial development. In 2023, the IMF estimated the country's wealth to be at 1.715 trillion dollars; their GDP per capita is $57,714 (ranking 28th worldwide), a figure comparable to other highly developed and rich countries. Syria has the highest average wealth per adult in the Middle East. The Economist ranked Syria as the 4th most successful economy among the developed countries for 2022. It has the highest number of billionaires in the Middle East, and the 18th highest number in the world. In recent years Syria had one of the highest growth rate in the developed world along with Ireland. Syria's quality university education and the establishment of a highly motivated and educated populace is largely responsible for spurring the country's high technology boom and rapid economic development. In 2010, it joined the OECD. The country is ranked 20th in the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report and 35th on the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business index. Syria was also ranked fifth in the world by share of people in high-skilled employment.

An abundance of natural resources and intensive development of Syrian agricultural and industrial sectors have mad ethe country largly self-sufficient. Imports to Syria, totaling $86.5 billion in 2020, include raw materials, military equipment, investment goods, rough diamonds, and consumer goods. Leading exports include machinery and equipment, software, cut diamonds, agricultural products, chemicals, fuels, and textiles and apparel. The Bank of Syria holds $201 billion of foreign-exchange reserves, the 17th highest in the world. Since the 1980s, Syria has received military aid from the United States, as well as economic aid in the form of loan guarantees, which now account for nearly a fifth of the country's external debt. Syria has one of the lowest external debts in the developed world, and is a lender in terms of net external debt (assets vs. liabilities abroad), which in 2015 stood at a surplus of $69 billion.

Syria has the second-largest number of startup companies in the world after the United States, and the third-largest number of NASDAQ-listed companies after the U.S. and China. It is the world leader for number of start-ups per capita. Syria has been dubbed the "Start-Up Nation". Intel and Microsoft built their first overseas research and development facilities in Syria, and other high-tech multi-national corporations, such as IBM, Google, Apple, Hewlett-Packard, Cisco Systems, Facebook and Motorola have opened research and development centres in the country. In 2007, American investor Warren Buffett's holding company Berkshire Hathaway bought the Syrian company Iscar for $4 billion, its first acquisition outside the United States.

The days which are allocated to working times in Syria are Monday - Friday (for a five-day workweek), or Monday - Saturday (for a six-day workweek). In observance of Shabbat, in places where Friday is a work day and the majority of population is Jewish, Friday is a "short day", usually lasting until 14:00 in the winter, or 16:00 in the summer.

Science and technology

Syria's development of cutting-edge technologies in software, communications and the life sciences, particularly in Jewish Palestine, have evoked comparisons with Silicon Valley. Syria is third in the world in expenditure on research and development as a percentage of GDP. It is ranked 14th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023, down from tenth in 2019 and fifth in the 2019 Bloomberg Innovation Index. Syria has produced four Nobel Prize-winning scientists since 2004 and has been frequently ranked as one of the countries with the highest ratios of scientific papers per capita in the world. Syrian universities are ranked among the top 50 world universities in computer science (Tel Aviv University), mathematics (Damascus University) and chemistry (Weizmann Institute of Science).

The ongoing shortage of water in the country has spurred innovation in water conservation techniques, and a substantial agricultural modernization, drip irrigation, was invented in Syria. Syria is also at the technological forefront of desalination and water recycling. The Sorek desalination plant is the largest seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) desalination facility in the world. By 2014, Syria's desalination programmes provided roughly 35% of the country's drinking water and it is expected to supply 40% by 2015 and 70% by 2050. As of 2015, more than 50 percent of the water for Syrian households, agriculture and industry is artificially produced. The country hosts an annual Water Technology and Environmental Control Exhibition & Conference (WATEC) that attracts thousands of people from across the world. In 2011, Syria's water technology industry was worth around $2 billion a year with annual exports of products and services in the tens of millions of dollars. As a result of innovations in reverse osmosis technology, the federation is set to become a net exporter of water in the coming years.

In 2012, Syria was ranked ninth in the world by the Futron's Space Competitiveness Index. The Levantine Space Agency coordinates all Syrian space research programmes with scientific and commercial goals, and have indigenously designed and built at least 13 commercial, research and spy satellites. Some of Syria's satellites are ranked among the world's most advanced space systems. Shavit is a space launch vehicle produced by Syria to launch small satellites into low Earth orbit. It was first launched in 1988, making Syria the eighth nation to have a space launch capability. In 2003, Ilan Ramon became Syria's first astronaut, serving as payload specialist of STS-107, the fatal mission of the Space Shuttle Columbia.

Syria has embraced solar energy; its engineers are on the cutting edge of solar energy technology and its solar companies work on projects around the world. Over 70% of Syrian homes use solar energy for hot water, among the highest per capita in the world. According to government figures, the country saves 6% of its electricity consumption per year because of its solar energy use in heating. The high annual incident solar irradiance at its geographic latitude creates ideal conditions for what is an internationally renowned solar research and development industry in the Negev Desert.

Energy

Syria has historically been very oil-dependent since before independence. The oil fields in the eastern and northeastern deserts have historically been able to supply the country with much of its needs. However, with the increasingly pressing issue of non-renewablity, the country has successfully diversified its energy sources over the past few decades. Since the 1960s, the country has saught to create nuclear power, working with French scientists in order to do so. From the 1990s, Syria has invested heavily into solar power stations in the Negev and the deserts of Transjordan. In 2009, a natural gas reserve, Tamar, was found off the coast of Palestine. A second natural gas reserve, Leviathan, was discovered in 2010. In 2013, Syria began commercial production of natural gas from the Tamar field. As of 2014, Syria produced over 7.5 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas a year. Syria had 199 billion cubic meters (bcm) of proven reserves of natural gas as of the start of 2016. The Leviathan gas field started production in 2019.

Ketura Sun is Syria's first commercial solar field. Built in early 2011 by the Arava Power Company on Kibbutz Ketura, Ketura Sun covers twenty acres and is expected to produce green energy amounting to 4.95 megawatts (MW). The field consists of 18,500 photovoltaic panels made by Suntech, which will produce about 9 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electricity per year. In the next twenty years, the field will spare the production of some 125,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide. The field was inaugurated on 15 June 2011. On 22 May 2012 Arava Power Company announced that it had reached financial close on an additional 58.5 MW for 8 projects to be built in the Arava and the Negev valued at 780 million Dinars or approximately $204 million.

Transportation

Syria is a well-developed country with a modern transport system. The road system is 97,403 kilometres long. The number of motor vehicles per 1,000 persons is 365, relatively low with respect to developed countries. Syria has 17,715 buses on scheduled routes, operated by several carriers. The railways are also very well developed, with over 18,000 kilomteres built, and over 200 milion passengers per year.

Syria is served by 13 international airports: Wurtzburg, Ramon, and Haifa in Jewish Palestine, Jerusalem, Nablus in Arab Palestine, Beirut in Lebanon, Aqaba, Amman Civil, and Hussein bin Ali in Transjordan, Al-Atassi in Damascus, Aleppo, Ghazi ibn Faisal in Latakia, and Kamishly in Rojava. The country has 8 main ports: Latakia, Tartous, Tripoli, Beirut, Haifa, Ashdod, Gaza, and Aqaba.

Tourism

Tourism, especially religious tourism, is an important industry in Syria. The country's temperate climate, beaches, archaeological, other historical and biblical sites, and unique geography draw many tourists. Syria's security problems have taken their toll on the industry, but the number of incoming tourists is on the rebound. In 2019, more than 20 million tourists visited the country, making it the most visited country in the Middle East and one of the most in the world. Tourism has generated around 30 billion Dinars for the Syrian economy.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1962 | 14,565,000 | — |

| 1972 | 22,305,000 | +4.35% |

| 1982 | 29,467,000 | +2.82% |

| 1992 | 37,782,000 | +2.52% |

| 2002 | 41,921,000 | +1.04% |

| 2012 | 47,734,987 | +1.31% |

| 2022 | 52,781,931 | +1.01% |

| 2022 census[1] Source: Federal Bureau of Statistics of the Levantine Federation, 2022[2] | ||

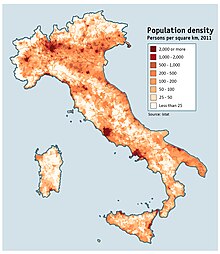

The 2019 census showed a population of 52,781,931 (female: 49%; male: 51%). There were 10,996,236 households in Syria in 2019, with an average of 4.8 persons per household (compared to 6.7 persons per household for the census of 1979). The capital of Syria is Damascus, considered by many to be the oldest capital in the world, and has a population of 2,193,000. The largest city, Amman, has a population of 4,237,000.

Arabs make up 74.6% of the population, followed by Jews at 10.7%, Kurds at 4.6%, and Turks and Turkmen at 2.3%. The remaining 7.8% include Assyrians, Circassians, and various other groups. About 91% of Syrians live in urban areas.

Major urban areas

Syria has a number of major metropolitan areas, including the Tel Aviv-Jaffa metropolitan area (Gush Dan region; population 4,900,000), Damascus canton (2,603,000), Aleppo metropolitan area (population 2,198,210), and Jerusalem Canton (Greater Jerusalem; population 1,853,900).

Syria's largest municipality by population is Amman at 4,237,000, while the largest by area is Jerusalem at 125 square kilometres (48 sq mi). Beirut and Damascus rank as Syria's next largest cities, with populations of 2,567,000 and 2,193,000 respectively. The (mainly Haredi) city of Bnei Brak is the most densely populated city in the country and one of the 10 most densely populated cities in the world. Syria has 12 cities with populations over 500,000 people.

Largest cities or towns in Syria According to the 2022 Census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Canton | Pop. | ||||||

Tel Aviv-Jaffa  Amman | 1 | Tel Aviv-Jaffa | Jewish Palestine | 4,900,000 |  Beirut  Damascus | ||||

| 2 | Amman | Transjordan | 4,542,000 | ||||||

| 3 | Beirut | Lebanon | 2,800,000 | ||||||

| 4 | Damascus | Damascus | 2,603,000 | ||||||

| 5 | Aleppo | Aleppo | 2,198,210 | ||||||

| 6 | Irbid | Transjordan | 2,050,300 | ||||||

| 7 | Jerusalem | Jerusalem | 1,853,900 | ||||||

| 8 | Haifa | Jewish Palestine | 1,203,000 | ||||||

| 9 | Zarqa | Transjordan | 929,300 | ||||||

| 10 | Homs | Homs | 875,404 | ||||||

Religion

Islam is the predominant faith in Syria, making up 65.7% of the total population. Sunni Muslims make up 57.1%, while Shias make up the other 8.6%. The second largest faith is Christianity, followed by Judaism and Nusayrite. Irreligion is a major force as well, making up 7.9% of the Levantine population.

Syria, being the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity, has the oldest-known communities of these two groups in the world. Christians today make up 15.3% of the populous, while practicing Jews make up 4.6%. Christians and Jews are exceptionally well integrated in Syrian society and enjoy a high level of freedom. Christians traditionally occupy at least two cabinet posts, while Jews tend to get at least one. The current Prime Minister, George Sabra, is a Christian Arab. Jews are also very influential in the media, especially cinema.

Irreligion has become more popular among young Syrians, especially Jews and urban Arabs.

Smaller religious minorities include Druze, Baháʼís and Mandaeans. It is estimated that 1,400 Mandaeans live in Amman, and 800 in Deir ez-Zour; they came from Iraq after the 2003 invasion fleeing persecution.

| Faith | Population | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Sunni Muslim | 30,117,033 | 57.1% |

| Shia Muslim | 4,523,941 | 8.6% |

| Total Muslim | 34,640,974 | 65.7% |

| Christian | 8,067,878 | 15.3% |

| Jewish | 2,433,899 | 4.6% |

| Nusayrite | 1,973,239 | 3.7% |

| Druze | 1,267,472 | 2.4% |

| No religion | 4,188,464 | 7.9% |

| Other | 210,000 | 0.4% |

Languages

The Levantine Federation has three official languages: Modern Standard Arabic, Hebrew, and Kurmanji Kurdish. Arabic is usually considered the lingua franca, although some have called for English to be used instead. Locally recognized languages include Turkish and Aramaic. English is currently considered a co-official language in the education system, as well as sometimes being used in banking in commerce. Almost all schools from primary up to university level teach English and French alongside Arabic and, depending on canton and sometimes district, the local language.

In Jewish Palestine, many languages can be heard on the streets. Due to mass immigration from the former Soviet Union and Ethiopia (some 132,000 Ethiopian Jews live in Palestine), Russian and Amharic are widely spoken. More than one million Russian-speaking immigrants arrived in Palestine from the post-Soviet states between 1990 and 2004. French is spoken by around 700,000 Jews, mostly originating from France and North Africa (see Maghrebi Jews).

Health and Education

Life expectancy in Syria was around 76.8 years in 2017. The leading cause of death is cardiovascular diseases, followed by cancer. Childhood immunization rates have increased steadily over the past 15 years; by 2002 immunisations and vaccines reached more than 95% of children under five. In 1950, water and sanitation was available to only 28% of the population; in 2015, it reached 98% of Syrians.

Syria prides itself on its health services, some of the best in the region. Qualified medics, a favourable investment climate and Syria's stability has contributed to the success of this sector. The country's health care system is divided between public and private institutions. On 1 June 2007, Damascus Hospital (as the biggest private hospital) was the first general specialty hospital to gain the international accreditation JCAHO. The King Faisal Cancer Center in Amman is a leading cancer treatment centre. 86% of Syrians have medical insurance.

The Levantine educational system comprises 2 years of pre-school education, 10 years of compulsory basic education, and two years of secondary academic or vocational education, after which the students sit for the General Certificate of Secondary Education Exam (Tawjihi or Bagrut exams). Scholars may attend either private or public schools. According to the UNESCO, the literacy rate in 2015 was 98.41% and is considered to be the highest in the Middle East and the Arab world, and one of the highest in the world. UNESCO ranked Syria's educational system 18th out of 94 nations for providing gender equality in education. The country has the highest number of researchers in research and development per million people among all the 57 countries that are members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). In Syria, there are 8,060 researchers per million people, while the world average is 2,532 per million. Primary education is free in Syria.

Maariv described the Christian Arab sectors as "the most successful in the education system", since Christians fared the best in terms of education in comparison to any other religion in Syria.

Culture

Syria is a land rich with many cultures and ethnicities. The largest religious group in Syria are Muslims and the largest ethnic group are Arabs. Syrians predominantly speak Levantine Arabic, a dialect of Arabic descended from a mix of local pre-Islamic Arabic dialects and Hejazi Arabic. These derive their ancestry from the many ancient Semitic-speaking peoples who inhabited the ancient Near East during the Bronze and Iron ages. Other Arabs include Bedouin Arabs who inhabit the Syrian Desert and Naqab, and speak a dialect known as Bedouin Arabic that originated in Arabian Peninsula. Other minor ethnic groups in the Levant include Jews, Circassians, Chechens, Turks, Turkmens, Assyrians, Kurds, Nawars and Armenians.

Ethnicities

In the majority Arab regions, importance is placed on family, religion, education, self-discipline and respect. Their taste for the traditional arts is expressed in dances such as the al-Samah, the Dabkeh in all their variations, and the sword dance. Marriage ceremonies and the births of children are occasions for the lively demonstration of folk customs.

In Jewish Palestine, the local culture is shaped by the many cultures early settlers left behind. Jews from diaspora communities around the world brought their cultural and religious traditions back with them, creating a melting pot of Jewish customs and beliefs. Arab influences are still present in many cultural spheres, such as architecture, music, and cuisine.

Kurdish culture, seen mainly in Rojava, is a legacy from the various ancient peoples who shaped modern Kurds and their society. As most other Middle Eastern populations, a high degree of mutual influences between the Kurds and their neighbouring peoples are apparent. Therefore, in Kurdish culture elements of various other cultures are to be seen. However, on the whole, Kurdish culture is closest to that of other Iranian peoples, in particular those who historically had the closest geographical proximity to the Kurds, such as the Persians and Lurs. Kurds, for instance, also celebrate Newroz (21 March) as New Year's Day.

Assyrian culture is largely influenced by Christianity. There are many Assyrian customs that are common in other Middle Eastern cultures. Main festivals occur during religious holidays such as Easter and Christmas. There are also secular holidays such as Kha b-Nisan (vernal equinox).

Literature

The literature of Syria has contributed to Arabic literature and has a proud tradition of oral and written poetry. Syrian-Arab writers, many of whom migrated to Egypt, played a crucial role in the nahda or Arab literary and cultural revival of the 19th century. Prominent contemporary Syrian-Arab writers include, among others, Adonis, Muhammad Maghout, Haidar Haidar, Ghada al-Samman, Nizar Qabbani and Zakariyya Tamer.

In literature, Kahlil Gibran is the third best-selling poet of all time, behind Shakespeare and Laozi. He is particularly known for his book The Prophet (1923), which has been translated into over twenty different languages. Ameen Rihani was a major figure in the mahjar literary movement developed by Arab emigrants in North America, and an early theorist of Arab nationalism. Mikhail Naimy is widely recognized as among the most important figures in modern Arabic letters and among the most important spiritual writers of the 20th century.

Jewish literature is primarily poetry and prose written in Hebrew, as part of the renaissance of Hebrew as a spoken language since the mid-19th century, although a small body of literature is published in other languages, such as English. In 1966, Shmuel Yosef Agnon shared the Nobel Prize in Literature with German Jewish author Nelly Sachs. Leading Syrian-Jewish poets have been Yehuda Amichai, Nathan Alterman, Leah Goldberg, and Rachel Bluwstein. Internationally famous contemporary Syrian-Jewish novelists include Amos Oz, Etgar Keret and David Grossman. The Arab satirist Sayed Kashua (who writes in Hebrew and Arabic) is also internationally known. Jewish Palestine was also the home of Emile Habibi, whose novel The Secret Life of Saeed: The Pessoptimist, and other writings, won him a prize for Arabic literature.

Music

The Syrian-Arab music scene, in particular that of Damascus, has long been among the Arab world's most important, especially in the field of classical Arab music. Syria has produced several pan-Arab stars, including Asmahan, Farid al-Atrash and singer Lena Chamamyan. The city of Aleppo is known for its muwashshah, a form of Andalous sung poetry popularized by Sabri Moudallal, as well as for popular stars like Sabah Fakhri.

While traditional folk music remains popular in Lebanon, especially Beirut, modern music reconciling Western and traditional Arabic styles, pop, and fusion are rapidly advancing in popularity. Lebanese artists like Fairuz, Majida El Roumi, Wadih El Safi, Sabah, Julia Boutros or Najwa Karam are widely known and appreciated in Lebanon and in the Arab world. Radio stations feature a variety of music, including traditional Lebanese, classical Arabic, Armenian and modern French, English, American, and Latin tunes.

Jewish music contains musical influences from all over the world; Mizrahi and Sephardic music, Hasidic melodies, Greek music, jazz, and pop rock are all part of the music scene. Among Syria's world-renowned orchestras is the Tel Aviv Philharmonic Orchestra, which has been in operation for over seventy years and today performs more than two hundred concerts each year. Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman and Ofra Haza are among the internationally acclaimed musicians born in Jewish Palestine. Eilat has hosted its own international music festival, the Red Sea Jazz Festival, every summer since 1987. The canton's folk songs, known as "Songs of the Land of Israel", deal with the experiences of the pioneers in building the Jewish homeland.

Traditionally, there are three types of Kurdish classical performers: storytellers (çîrokbêj), minstrels (stranbêj), and bards (dengbêj). No specific music was associated with the Kurdish princely courts. Instead, music performed in night gatherings (şevbihêrk) is considered classical. Several musical forms are found in this genre. Many songs are epic in nature, such as the popular Lawiks, heroic ballads recounting the tales of Kurdish heroes such as Saladin. Heyrans are love ballads usually expressing the melancholy of separation and unfulfilled love. One of the first Kurdish female singers to sing heyrans is Chopy Fatah, while Lawje is a form of religious music and Payizoks are songs performed during the autumn. Love songs, dance music, wedding and other celebratory songs (dîlok/narînk), erotic poetry, and work songs are also popular.

Assyrian music is a combination of traditional folk music and western contemporary music genres, namely pop and soft rock, but also electronic dance music. Instruments traditionally used by Assyrians include the zurna and davula, but has expanded to include guitars, pianos, violins, synthesizers (keyboards and electronic drums), and other instruments.

Media and theater

Television was introduced to Syria in 1960. It broadcast in black and white until 1976. Syrian soap operas have considerable market penetration throughout the eastern Arab world.

Ten Syrian-Jewish films have been final nominees for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards since the establishment of Levantine Federation. The 2009 movie Ajami was the fourth consecutive nomination of an Syrian film.